Insofar as there is any small thing in baseball, one pitch is as discrete as it can get. If you are a good pitcher—at one point, say, the best relief pitcher in baseball—you can work around a first-pitch ball, even when trying to close out the ninth inning of a game. If you have that skill and you could, hypothetically, help someone else out with very, very little potential consequence to yourself, well. It's not conspiring to throw a game. It's just one pitch.

Which is to say that the logic for Emmanuel Clase—who was in the midst of a five-year, $20 million contract when he was indicted for manipulating prop bets—is not necessarily so difficult to understand. The new landscape of modern gambling permits betting on such low-stakes minutiae, and consequently makes bets easier to manipulate and, evidently, harder to detect. According to the indictment, Clase had been involved in the pitch-rigging scheme since May 2023; over the past two years, he had netted the bettors $400,000. Though the indictment only names a couple of pitches from June 2023 as explicit pre-2025 examples, it makes reference to hundreds. That span of time encompasses Clase's 2024 season, in which he posted a 0.64 ERA and came third in Cy Young voting, though the indictment does not explicitly state that he manipulated bets during that season.

It is difficult to say exactly why Clase only got caught after his teammate, starter Luis Ortiz, joined the scheme. Suspicious betting patterns on Ortiz's pitches were the first ones flagged by a betting integrity firm, or, at least, the first ones reported to have been flagged (one of the many things learned from the Shonei Ohtani–Ippei Mizuhara scandal is that the order of reporting can confuse a story). According to the indictment, the wagers on Ortiz's June 15 slider to Randy Arozarena totaled $13,000, and won the two bettors $26,000. In the 2023 examples provided in the indictment, the original wagers are not stated, but it is noted that the bettors had collectively won $27,000, $38,000, and $58,000 on individual pitch bets.

Perhaps the individual bets on Ortiz's pitches were greater, even if the payout was lesser. Perhaps Ortiz being a starter made extraneous bets more notable, or more easily detectable. Perhaps betting integrity firms have improved their methods over the years as gambling scandals become increasingly common in sports. But the question of why is a little less relevant than the fact that it happened anyway—that, if the allegations are true, Clase had either been doing this since 2023 or had done it as early as 2023, and nobody knew until now.

The span of time renders the ex post facto sleuthing conducted in the space between Clase's suspension and the indictment either irrelevant or questionable. If the percentage of wasted balls on the first pitch of an outing was disproportionately high in 2025, but not in 2024, does that indicate he didn't manipulate pitches in his best year in MLB? Or does this just continue to indicate the small sample size issues with first-pitch balls to start? You can tell a different story depending on how you slice the stats. Clase threw a disproportionately higher percentage of first-pitch balls if the batter was his first of the inning, compared to all other occasions in both 2025 (44.2 percent compared to 34.6 percent) and 2024 (36.2 percent compared to 31.7 percent), but not in 2023, when we know he is alleged to have been participating (41.2 percent compared to 41.0 percent).

What is frustrating here is that in spite of the modern availability of Statcast search that makes it so much easier to hunt down video footage or try to confirm statistics, the viewer can't truly tell from either numbers or her own eyes. There can be video compilations of the first pitches Clase threw, which are quite funny in retrospect, but prove little on their own. The only way to detect the direct influence of gambling on sports is contingent on sportsbooks' desire not to lose money—that is, these betting integrity firms that flag based on the bets. And yet even those safety nets can and evidently have failed, if Clase had done this in 2023 and not been caught.

As far as the integrity of a game result, or even Clase's personal statistics, his wasted opening pitches had little impact. The egregious June 3, 2023, pitch thrown to Ryan Jeffers cited in the indictment? Clase struck Jeffers out, then struck Willi Castro out, and then induced a groundout from Alex Kirilloff to get the save. He was a little less fortunate four days later, on June 7, as he wound up walking Jarren Duran after his first-pitch ball, but no matter: Clase proceeded to then strike out Connor Wong and Rob Refsnyder, and induce a hard-hit flyout from Christian Arroyo to get the save, again.

If fans still care even knowing that the overall game result wasn't shaped by the scheme, it is not because they are sickos who care about every single regular-season pitch—or, at least, it is not necessarily that. The biggest effect of a scandal like this is that the viewer now has doubt about what she sees, even if it is legitimate. Nobody wants a fixed outcome or a foregone conclusion. What is amusing and incidentally heroic about Andy Pages ruining an eight-leg parlay thanks to his poor plate discipline is the proof that still, in baseball, there is only so much anybody can control. Of course, now one can imagine a situation in which a pitcher tips off his guys that he's going to throw a first-pitch ball, and a batter tips off his guys that he's going to swing at the first pitch to guarantee a strike, and we will be granted the most depraved swing-ball combination you've ever seen in your life.

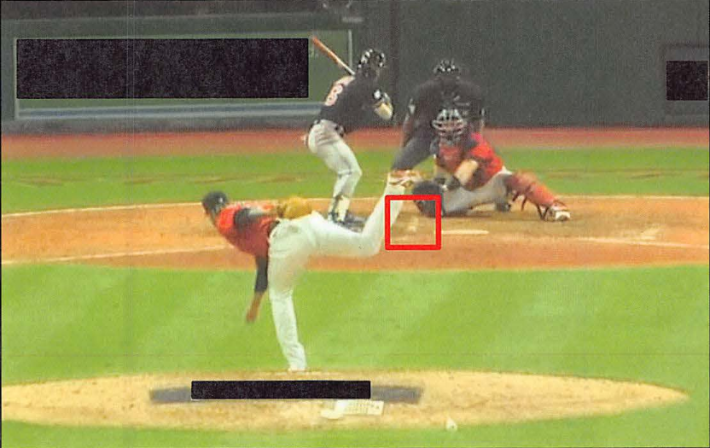

The blurry, low-resolution, Bob Nightengale–esque quality to the photos provided in the indictment are an expression of how it feels to be looking at those pitches in retrospect. (Question: Does the United States District Court of the Eastern District of New York know about how to fetch videos from Statcast search?) You try to make sense of a fuzzy image with limited pixels; you draw a little red square around where the ball bounces in front of the plate; you do your best to block out all the advertising.

What was it like to have watched the pitch in real time, back in 2023? Well, if you were a Guardians fan, it would look like this. Clase spikes a 91-mph slider that bounces over the catcher's head. You get the mound advertisement for MOEN and the backstop advertisement for Cleveland Clinic Children's. You see the Bally score bug roll out underneath to start the inning, the animation still playing as Clase begins his leg kick. And just as the pitch finishes, the score bug has settled, as well, into its advertising imperative: WATCH THE GUARDIANS ALL SEASON ON BALLY SPORTS APP.