Recently I have been watching a lot of tennis, and thus trying to learn about tennis. This, as it turns out, is very difficult, because tennis is not a sport that wants to teach you about itself.

If you do not have knowledgeable colleagues whom you can pester with technical questions, the best way to learn about a new sport should be through a well-executed broadcast that enables a correlation between time spent watching and things learned. This broadcast would ideally have an enthusiastic primary commentator who seems to like the sport and can explain both narrative context and what is happening; an analyst who can explain why things are happening with more knowledge than the average viewer; and, for the calculator casuals, some statistics that help the viewer contextualize all of the above.

Depending on how you count, tennis has approximately zero of these elements on a consistent level. The legwork required to learn from a tennis broadcast, as it exists in the United States, is extraordinary. The main television broadcast during Grand Slams is, at its best, inoffensive; you are often better off with smaller tournaments or the World Feed, where you might catch Mark Petchey or Andrea Petkovic, and learn a thing or two. Occasionally you will get enlightening data on return position (with slightly less enlightening visualization) and serve placement statistics, but usually, if you happen to be watching an ATP match, you will get served a Performance Rating or Shot Quality metric instead. On a broadcast, the packaging for that metric looks something like this:

What does this tell the spectator? Even knowing nothing about what goes into these insights, we can still intuit that a Performance Rating exists on a scale of 0 to 10, with 7.4 as the tour's collective average. Jannik Sinner's performance, then, would be close to perfect. Meanwhile Daniel Altmaier's is quite poor, though without knowing the floor of the statistic, how poor is still in question. Without knowing what happened in the first set, it is possible to intuit from the graphic that Sinner probably rolled Altmaier. Knowing what happened in the first set, which is that Sinner did roll Altmaier, 6-0, the graphic tells you nothing the scoreline does not. Was Altmaier playing poorly because Sinner was playing well, or vice versa? What did Sinner actually do that made him so dominant?

In order to try to learn more about Performance Rating, the viewer must go outside of the broadcast itself and to the ATP's website. On the bottom of the site's InfoSys ATP Stats Tennis Data Innovations Insights Leaderboard lies an explanation for what Performance Rating is: "0–10 rating for each player. Incorporates both the shot quality of every stroke and how often each player is in attack in the rally and if they convert their advantage to win the point or turnaround a defensive position to steal the point." This is a longwinded way to say that Performance Rating is the type of advanced statistic that takes a plethora of different variables (shot quality, whatever that means; converting advantages, however that is defined; and so on) and tries to boil them down to one number.

Alternatively, the viewer can skip the written explanation and attempt to find another graphic, this time on the official Tennis Insights Instagram. Here is what that graphic might look like:

Here are some labels for the variables that go into Performance Rating. Also, the post reveals that a 9.61, which is what Sinner wound up finishing with, was his second-best performance of the year. But wait—what does serve or forehand quality mean here? Before going the extra step of conducting our own research, let's see if we can learn from another broadcast graphic:

This graphic is marginally more informative than the one prior. We can again intuit that "quality" metrics are also on a scale of 0 to 10, which probably means that they are also some form of one-number-fits-all advanced stat. (Which then means that Performance Rating is a one-number-fits-all advanced stat that takes in four other one-number-fits-all advanced stats as variables.) The graphic states that Sinner's forehand has been better than Felix Auger-Aliassime's, over both the match and the past year. It also says that Sinner's forehand at this point in the match—soon to be 4-2 in Sinner's favor in the first set—has been better than his average forehand, and that Auger-Aliassime's has been worse. What it does not explain, again, is why. What characteristics make Sinner's forehand better than Auger-Aliassime's, both in general and during this match? How and why is Auger-Aliassime's forehand worse than his average? How and why is Sinner's better than his average?

At a certain level of tennis knowledge (i.e. mine), some of the variables encapsulated in that 0-to-10 number can be intuited: spin, speed, shot depth. Indeed, scanning the InfoSys ATP Stats Tennis Data Innovations Insights Leaderboard once again yields the variables that go into Forehand Quality: "Analysing the spin, speed, landing coordinate, bounce angle, bounce deviation, and phase of play to generate a score 0/10 for every forehand shot." The lack of parallelism with the Performance Rating description can be forgiven. It gets a little muddled if you go to the Tennis Insights page, which gives this graphic that has slightly different variables:

The incorporation of winners is new, and, if you are too well-informed, confusing in its discrepancy from the written description; the absence of shot location metrics, which just may not be as sexy on a graphic, raises similar questions. Of course, if the point of one-number-fits-all metrics like these is to eliminate any worry about what goes into making the sausage, it's not surprising that someone wouldn't like what they see if they look a little closer.

These Insights metrics exemplify the worst tendencies of these formless one-number-fits-all statistics that are normalized onto a scale of 0 to 10. Take soccer's xG as a better example of a similar type of statistic. Pure accuracy of the analysis aside, xG at least has a preexisting unit (goals), scale (anywhere from 0 to 1), and has interpretative purpose (cumulatively, the number of goals a team should expect to score on the shot chances it generates). In baseball, wOBA lacks a unit and physical representation, but is intentionally normalized onto a scale that is easily interpreted to fans (from .200 to .400) and, most importantly, has its weights and variables publicized.

Both Performance Rating and Shot Quality have none of the above. What is the relationship between a rating of 7.5 and 8.0? Linear? Quadratic? Is someone with an 8.0 rating five percent better than someone with a 7.5? What is one to do with a rating system that extends from 0 to 10 but has the lowest listed value on the leaderboard at 6.18? When the tour average is 7.4, is that just including the top 138 players on the ranking leaderboard, or does that include everyone? What is the theoretical peak performance that would yield a perfect 10? Does it even exist? Does it change year-to-year?

The existence of these sausage metrics suggests a vast quantity of data available behind the scenes, which is all the more a shame. On occasion, the broadcast will hint at something enlightening that could be illuminated by that data, if only it were publicly available. Daniil Medvedev hits flatter (i.e. with less spin) than the rest of the tour, in an ATP where RPMs are king. Despite his struggles this year, he has nevertheless had historic success with his forehand. Can we learn something from this, like the relationship between pace and spin, or how different play styles find success? Well, ATP Insights tells us that his forehand ranks 30th on tour, with a 7.63 rating. No need to ask too many questions here about what goes into making tennis what it is. It is easier to compare two numbers and take the larger one.

Here is what it's like trying to locate more complex statistics through the ATP website. Say you want to find the match statistics for the Paris Masters 1000 final between Sinner and Auger-Aliassime. From Sinner's player page, you click through to the "Stats" tab. This gives you a limited suite of the sort of statistics that pop up on Google's game widget: first serve percentage, break points saved, etc. Instead you click through to the "Activity" tab and click, somewhat unintuitively, on the 6-4, 7-6(3) score of his most recent match, which was against Auger-Aliassime. This takes you to a match page with the exact same sort of statistics that were on the "Stats" page. Clearly this is the wrong strategy.

Instead, you hover over the "Scores" tab on the banner and click through to the "Results Archive," which you probably should have done in the first place. You filter to "ATP Masters 1000" events and then select the results of the Paris Masters 1000. From here, you click on the "Stats" button in the little box of the Paris Masters Final. This takes you to a different stats page, which, on top of obvious Infosys advertising, has some promising-looking tabs, beyond the standard statistics that you land on: MatchBeats, CourtVision, Rally Analysis, Stroke Summary. MatchBeats takes you to an interesting, Infosys-branded point-by-point visualization of the entire match. I've always been a big fan of CamelCase. CourtVision takes you to an Infosys-branded "Oops! Something went wrong" display; if it should load, the ensuing visualization will be broken anyway. Rally Analysis provides some Infosys-branded stats for winners, forced errors, and unforced errors at bins of varying rally lengths. Pretty cool! Click on Stroke Summary, and you once again land on an Infosys-branded broken page.

The construction of a public database, complete with visualization, is a daunting undertaking. By contrast to the ATP, perhaps the most impressive version of this across all of sports is Baseball Savant, Major League Baseball's database and the de facto home for Statcast, its personal data collection tool and overarching brand name for resultant—but not proprietary—statistics. Savant is powered by a suite of data engineers and sabermetrics pioneer Tom Tango; it is the culmination of decades of community and statistical work in the sport, and enabled by a commitment to making data publicly available. It has beautifully rendered player pages, live game pages, visualizations, and leaderboards. One does not need to be a true advanced-stat believer to find utility in the site; it can just as easily serve as reference material to locate individual plays or pitches, or to confirm the eye test. Does Giancarlo Stanton actually swing the bat faster than anyone else? Yeah, he does. Can I see every single change-up Tarik Skubal threw this year? I sure can.

Advanced statistics are something sports leagues increasingly feel they should have, irrespective of execution. Among the American sports leagues, MLB has the aforementioned Statcast (powered by Google Cloud), the NFL has Next Gen Stats (powered by AWS), the NBA has the newly minted Inside the Game (powered by AWS), and the NHL has Edge (surprisingly absent a web services sponsor, though the "What's New" announcement on its landing page has a "presented by SAP" in one of its images). This mode of presentation hints at one motivation: Advanced stats provide an additional sponsorship opportunity, targeting a huge industry eager to flex the capacity of its services.

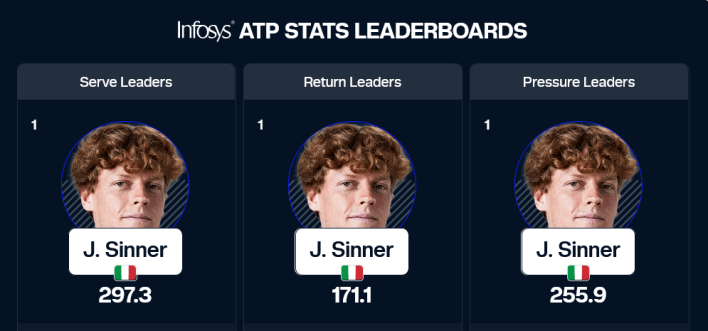

In the ATP's case, their partnership is primarily with Infosys, which is the official Digital Innovation Partner of the ATP. The first item on their partnership page encourages the viewer to download an app. Scroll down, and Infosys flexes their Serve and Return Tracker, declaring "from an eye on court to AI on court." Click "explore" and it takes you to the ATP Stats Leaderboard, again, but a different dropdown from the Insights page, with values that make even less intuitive sense. What does a 297.3 mean? A 171.1?

When a sports organization has no commitment to presenting useful information but wishes to have a tech sponsorship regardless, the statistics it churns out will inevitably cater to whatever marketing buzzwords its tech partner wishes to shoehorn in, rather than providing any utility to the sport itself. If statistic legitimacy is not the goal, and a full public database is too daunting a task, settling for a few sausage statistics is no trouble at all; simply aggregate some numbers together that can be posted to Instagram afterwards and labeled AI. The artificial intelligence itself is almost certainly a linear regression model that can be branded as AI by virtue of being machine learning; by the same logic, one may brand a simple k-NN algorithm as AI as well.

Learn who is behind a meaningless statistic and you can glean much of its purpose. The ATP's Insights are developed with TennisViz and Tennis Data Innovations. While TennisViz employs a separate team of data engineers, TDI is a co-led venture between the ATP and its media arm, ATP Media. The explicit goal of TDI is to "manage and commercialise data across a variety of global markets, including betting, media and performance." The site references that the vision is "to set the benchmark for effective commercial management of data assets and betting streaming in world sport."

Data has value to a sports league in two ways. In the first, it can be packaged for the public in a way that enriches the understanding of the sport itself. This has no immediate returns, but it helps to cultivate an informed and passionate viewership, which should always be worthwhile for a sport, if not its primary goal. A signal example of this would be the NBA's now defunct in-house stats website, which allowed anybody, at no cost, to mine advanced stats, generate on-demand visualizations, and watch (and analyze) video of every possession of every game—and which played a huge role in the explosion of basketblogging as a major source of league coverage in the years before digital media's economic collapse. In the second, the vast amount of data available to a sports governing body has value because it can be sold, or kept proprietary, or used for marketing. As one such example, the ATP's Tennis IQ tool, built primarily for players, warranted a press release with explicit emphasis that it is powered by PIF, the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia.

It is not a surprise that TDI (and by extension, the ATP), says "data assets" in the same breath as "betting streaming." Both can be extraordinarily profitable, even if they make things a little bit worse for everyone involved, including the ATP's own employees. Perhaps in another world, the Insights would be, at their material and philosophical worst, a mere irritation. In this one, they're irrevocably tied to everything aggravating about how sports are run these days. Why expect quality? Everything is marketing.