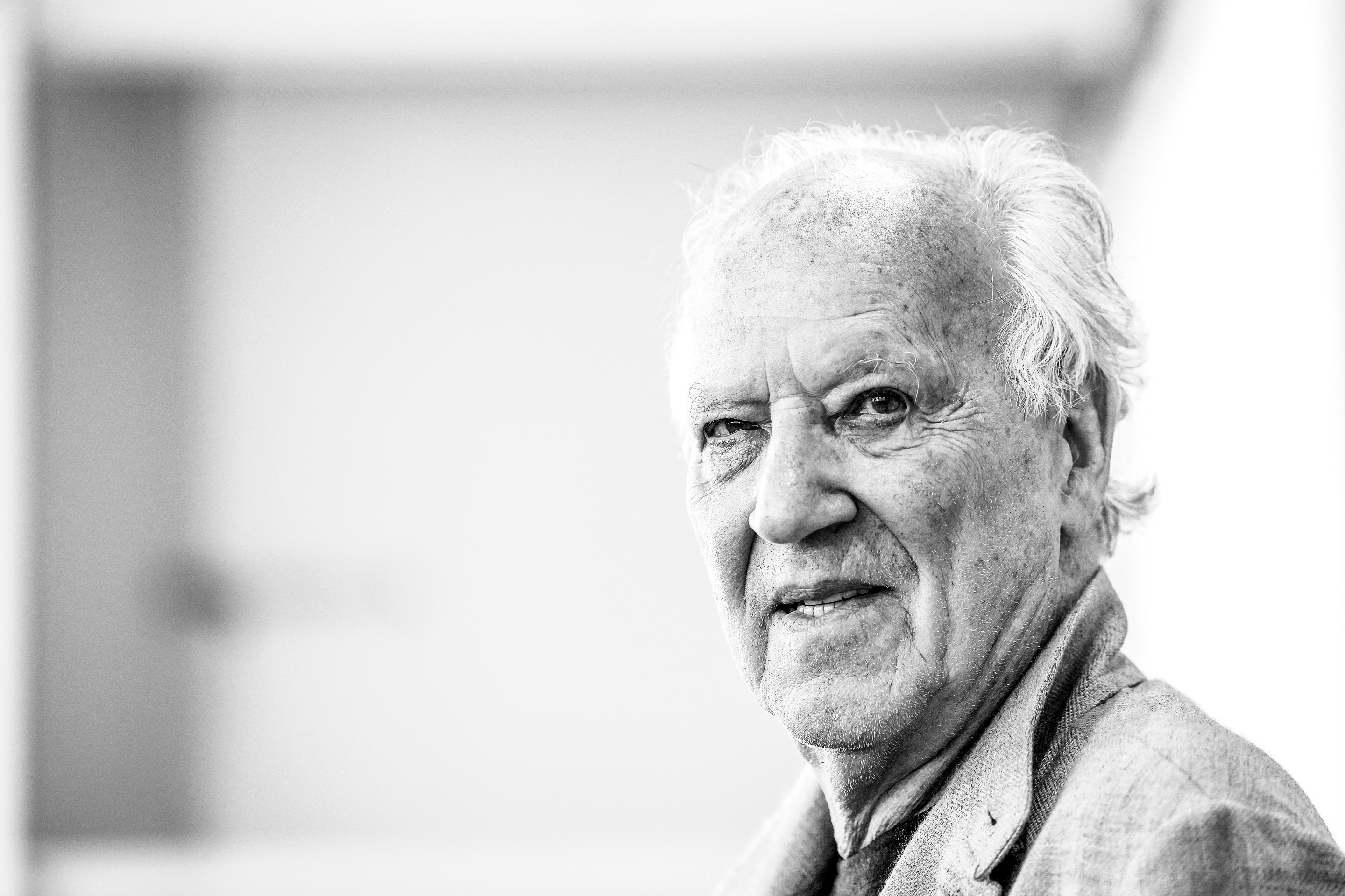

You might think of Werner Herzog’s new book, The Future of Truth, as the story of two animals.

On the front cover, you see the silhouette of a lone penguin, somewhere in the middle distance, setting off from icy tundra to the mountains. While never made explicit in the text, this image is an obvious reference to a memorable vignette from Herzog's 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World. While speaking to a penguin scientist, Dr. Engli, Herzog inquires about the possibility of "insanity in penguins."

"I don't mean that a penguin might believe that he or she is Lenin, Napoleon Bonaparte … but could they just go crazy, because they've had enough of their colony?"

After Engli gives him a non-committal answer, Herzog—being Herzog—does indeed find a penguin that has gone insane. Observing a group waddling toward their feeding grounds, he notices that one of their number has started to walk off in a complete other direction.

"Dr. Engli explained that even if he caught him [the penguin] and brought him back to the colony, he would immediately head right back for the mountains."

The penguin is headed for the interior of Antarctica. A more sober observer might simply call the animal disoriented; the animal is now almost certain to die. But Herzog sees something romantic in this penguin, something admirable. The penguin is about to experience something that no ordinary penguin ever would. The penguin has managed to liberate itself from, to transcend, the penguin-everyday. And so it has launched itself, I think Herzog must believe, into a different, higher strata of meaning, and of truth.

Herzog and the mad penguin are a kindred pair. As a filmmaker, Herzog has long sought to bring us tales from a more enchanted world. His protagonists—Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Timothy Treadwell, the Woodcarver Steiner, and others—have been quixotic freaks pushed to singular, though often futile, accomplishments by urges they are unable to justify in accordance with the norms of the society around them. And of course Herzog himself has become, over time, a central part of his films. Here is a man who has spent his entire adult life doing insane things to document the achievements of the insane. Notoriously, for Fitzcarraldo he even had a steamship hauled up a mountain in the jungle himself. By this point, he must be confident in his sense that he is himself among the greatest wonders in the world.

If the mad penguin has an opposite, then it is surely the Palermo Pig. Herzog tells us the story of the Palermo Pig early on in The Future of Truth, in chapter two. One day, or so the suspiciously all-too-Herzogian and unverifiable story goes, a pig at a Palermo market fell down a rubbish chute which was connected to the sewers.

"A metal grill caught the animal in the depths. Because the chute was so narrow, it wasn't possible to free the pig from its pickle, and stall owners and customers would occasionally toss rubbish down to the pig, which, according to the story, lived on for several years. It should be mentioned that the chute wasn't tubular, but four-sided. The pig in its prison came to assume a quadrilateral form, and when it was finally free—alive —it was ghostly pale, translucent as a minnow and had taken on a cube form, wobbly as a great hunk of Jello."

Ostensibly, the point of the story is that it tells us something about the impossibility of long-distance space travel. He thinks astronauts on their way to Alpha Centauri would arrive there as Palermo Pig–type beings. But in a way, Herzog already believes humans are becoming Palermo Pigs on Earth: a species rendered impotent and bent grotesquely out of shape by the technologies which now ineradicably structure our world. For such creatures meaning, and thus truth, are becoming increasingly difficult, even impossible. The Future of Truth, then, might be thought of as a book about how people need to embrace what few remaining opportunities we have to act like mad penguins, before we all become like pigs stuck in quadrilateral sewers.

Herzog, as both fans and philosophers might know, has a long and storied history with the concept of truth. Like his long-dead friend and collaborator Bruce Chatwin—whose influence was profound on this score—Herzog has been notorious for producing ostensibly nonfictional works in which the facts figure as something he is happy to manipulate for aesthetic purposes.

Herzog's reasons for doing this were first outlined in his much-circulated 1999 "Minnesota Declaration," the brief, 12-point manifesto in which he took aim at the assumptions about truth, and reality, which he tells us are informing cinema verité, although he might plausibly have taken aim at basically any form of aesthetic realism. For Herzog, cinema verité, in attempting to portray the facts simply "as they are," reaches merely a "superficial truth, the truth of accountants." In the Minnesota Declaration, Herzog rejects the identification of fact with truth: "Facts create norms, and truth illumination," and against this identification he posits the existence of "a deeper strata of truth in cinema … a poetic, ecstatic truth." Far from becoming apparent through the attempt to portray things objectively, or how they actually are, this deeper truth "can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization": by falsifying things, in short.

For years now, I have been fascinated by this notion of ecstatic truth. But it has at most been a philosophically intriguing notion: an idea which feels like it might solve quite a lot of problems to do with our thinking about truth, but which exists as yet exclusively on the level of vibe. If it is going to be rendered serviceable, then Herzogian ecstatic truth requires a whole lot of fleshing out.

The Future of Truth doesn't quite manage this. By Herzog's own admission it is no philosophical treatise: It is a short book, and quite cheerfully unsystematic. Chapters flit from concern to vaguely related concern like blog posts. In one of them, five whole pages—of a seven-page chapter, in a 110-page book—are given over to describing the plot of a Verdi opera. For all this, however, one does leave the book with a sufficiently deeper understanding of what Herzog means by truth, and why he fears for its future

For the most part, Herzog takes an autobiographical approach to the problem of truth, orienting the reader toward it by relating the ways in which it has occupied him over the course of his career. You get, for instance, a practical demonstration of how Herzog thinks ecstatic truth might be achieved through fabrication: The director dishes certain secrets to do with how he made his 1997 film Little Dieter Needs to Fly, encouraging his subject to artificially perform certain actions in order to establish his character. This was fakery, but in Herzog's view it was also deeply honest, since this was a character Herzog had genuinely, honestly gleaned through conversations with his subject Dieter Dengler. He just needed some way of symbolising it on film.

Another trick that Herzog lets us in on is his habit of attributing epigraphs to great thinkers, when they are in fact lines he has made up himself. The idea being that this lends them a gravitas they would otherwise lack. Lessons are drawn from anecdotes: A typical Herzog story finds him meeting with a French cult leader in a hotel in a run-down part of Greater Manchester, or stranded with Harmony Korine on an island off the coast of Panama, being mistaken for a priest.

While Herzog makes no extended attempt to relate his views to the vast philosophical literature on truth, a certain philosophical heritage is nonetheless made clear. Thus you get an explicit nod to the Heideggerian (but also Ancient Greek) notion of truth as aletheia, a word which translates more literally as "unconcealment." For Heidegger, too, truth is in no way fundamentally about being true to the facts. Rather, it is a process in which we, as subjects, are always actively involved: It is up to us to make things either "come to light" or not. And sometimes we are obliged to conceal certain things, in order to illuminate others.

Herzog likes the aletheia imagery, in part, because he sees in it certain affinities with the development of film: the picture taking shape in the chemical bath in the darkroom. Truth as unconcealment is thus, among other things, a filmmaker's sort of truth. "Leave aside for now the question of whether it's real or not. What I find so stirring is the process, the approximation, the emergence."

Another image throughout the book is of truth as a sort of journey, as a sort of striving. Truth, for Herzog, seems to involve a particularly intense experience of reality. Interestingly, he does think this experience can sometimes be brought about by facts. The Holocaust, for instance, is named as something which has a kind of "transcendent factuality" to it. A list of names of victims of the Holocaust is true, for Herzog, in a way that a list of names in a phone book isn't. But perhaps more paradigmatically, this experience is induced in a person by, yes, art—or simply by doing things. "The most intense experience of reality has been for me: traveling on foot," he writes. "The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot."

In just the same way, perhaps, as for 19th-century German philosophers "freedom" always ends up meaning the same thing as "reason," for Herzog truth can amount to the same thing as meaning. "[Truth] gives dignity and meaning to our existence." If there was no truth, Herzog implies, there would be no meaning to human life. And if truth is realized only in movement, in striving, in journey, then it is vital that the possibility of these experiences be preserved.

It is here that the future part of Future of Truth comes in. The book is concerned with the rise of AI, of its ability to generate things like deep fakes, and how this is likely to distort our experience of the world. On this score, Herzog is no luddite. He is willing to admit that AI might "offer us ideas and suggestions that never occurred to us," and he even relates a friendly conversation with Elon Musk. But what Herzog seems particularly taken with are the aspects of AI that its creators appear to be working most fervently to eliminate—its tendency to hallucinate, for instance. To this extent, when it comes to AI, Herzog seems enamored of the possibilities, but deeply unimpressed—as anyone with half a brain must be—with the realities.

It is at this point that the threat metaphorically represented by the Palermo Pig rears its square, translucent head. Like the Pig, people tend to be plastic in relation to their environment, and if their environment is totally unsuited to their nature, they will inevitably become, over time, some wholly unnatural version of themselves. Generative AI allows people to outsource their thinking to a machine. By making thinking too easy, AI threatens to make it impossible. The problem then is not that fake news or deep fakes state literal factual falsehoods, but that technology threatens to rob us of the need, and so the ability, to pursue truth, and thus meaning, for ourselves. Think of the apparently increasingly common habit of people using AI to plan their holidays for them. The singularity will surely not come when some machine has achieved some hypothetical super intelligence that will always be beyond individual, physical beings. It will come when Silicon Valley has successfully dumbed everyone down to the level of ChatGPT.

This is why everyone needs to be more like mad penguins, and less like pigs in tubes. If truth is indeed a journey, then there must always be searchers after it—in order for truth, as such, to be sustained. Since truth is ultimately about meaning, it is not the sort of thing that might ever persist indifferently, like a fact. Truth is not found in the lab, or on the accountant's balance sheet. Rather, it is something which emerges in the context of the crazy journey, or the quest. And so it's time to turn your back on the rest of the flock, and head for the mountains.