I started going back to the 1970s last winter because I was convinced everything and everyone else was, too. This was not a good time, and I was very much Not Having A Good Time in it; in retrospect, the decision to cope with the dread I felt at anticipating several brutal years of national self-harm by watching a bunch of movies in which Gene Hackman scowled and wore weird hats and drank what was very clearly some absolutely dogshit coffee out of paper cups was something close to the healthiest possible scenario. The idea, if there was an idea, was both to get attuned to the frequencies and manias of that particular low and dishonest decade in the hope that there might be some lessons there, and maybe also to remind myself that national moments of humiliation, failure, and loss come and go in the same ways that personal ones do.

That is, they pass. American history tells us that the problems that make all that trouble do not ever get resolved, let alone solved; we don't really do that here. This country loves its problems too much, or has just mistaken them for virtues so willfully and for so long that it can't imagine living without them; in the absence of a more representative politics, or maybe as a sort of satire of it, politics collapses into various ways to perform being upset. None of this is especially dignified, or remotely What You Want. All of it feels both like it is too dumb and unworkable to last, and like it is getting worse.

But if nothing ever really goes away, it is also true that bad times can be survived and outlasted, sometimes through heroic acts of resistance and refusal but mostly in the ways that people generally survive and outlast things, which is by being stubborn and keeping at it; there is nothing to do, really, but go about our respective and collective business as best we can. To lavish over and splash around in all those problems, to nurture them until they crowd out every other finer and more humane thing, is a luxury that only the strangest and most comfortable people can afford. Everyone else just lives their lives, and finds pleasure and hope wherever they can.

The '70s films and books I read during that Gene Hackman Winter were horrified by the right things, but ultimately stymied by the fact that their protagonists lacked the right tools for the necessary demolition work. The institutions wouldn't do it; they were broken or corrupt. An individual couldn't do it; the work was too big, and the scale of the corruption and rot too vast. This was what normal people watched at the movies, although that era also made big hits out of more reactionary fantasies like Walking Tall, where one man really does harness the power of violence to bring down the bad guys. It was based on a true story, although the truth of that story has emerged more fully in the years since and revealed that its hero was a liar who had created his own legend to cover up his own act of murder. Dark times, as I said.

But that couldn't be the whole story. For all the metastasis and malaise of that decade, people nevertheless filled those years with their lives. There is a lot to admire in both the concept and the craft of Ken Ohara's photo exhibition Contacts at The Whitney Museum in New York City, which is up through Feb. 8, but what I loved about it was how it revealed all that secret life in all its humdrum, happy-enough humanity.

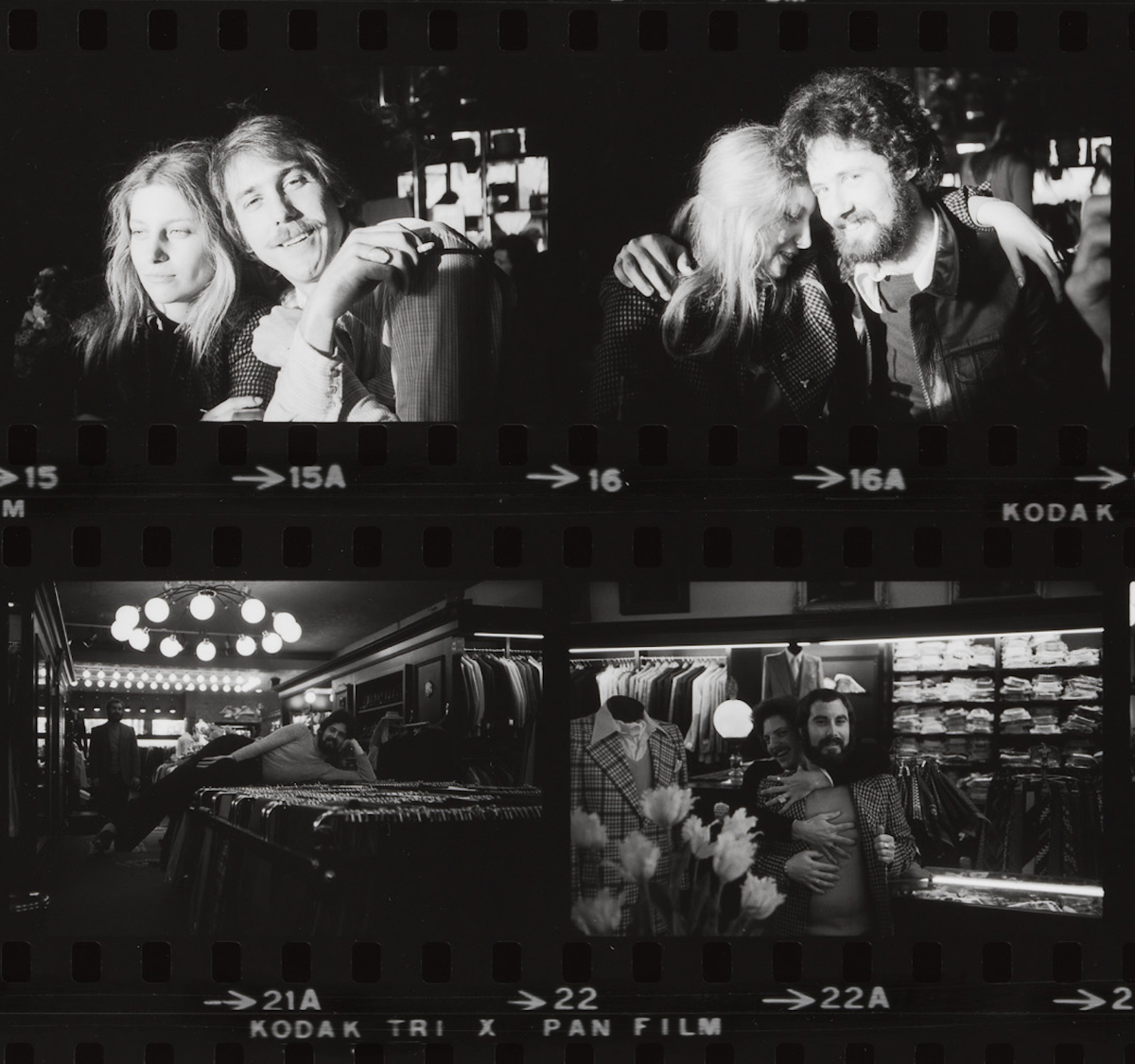

In 1974, Ohara began his project by sending his Olympus 35 RC camera, loaded with 35-millimeter film, to a name chosen at random out of the phone book. The camera came with instructions: the recipient was to photograph themselves and their lives and whatever else struck their fancy, and then return the camera to Ohara with the name and address of its next recipient. Ohara developed the photos his collaborators sent back, reloaded the camera, and then sent it back on as directed. This went on for two years, during which time Ohara's camera went to 100 people in 36 states. The camera was in offices with extravagant '70s aesthetics and in barrooms and bowling alleys where people took party pics and rudimentary selfies and was passed between family members in houses and apartments; people took pictures of funny signs they saw in shop windows, and big trucks, and cute animals, and their televisions.

When the recipients had questions for Ohara, he answered them by phone or letter; when the camera had problems, he troubleshot them. "The purpose of this project is to develop a feeling of trust and friendship between each one of us," Ohara wrote in the instructions that came with the camera. "The pictures you take will act as a bridge from one to another and, at the same time, the work involved before these pictures are taken will be of equal importance." When Ohara pulled the project together as an exhibition, he displayed the images as a series of enlarged contact sheets and not as individual photos—a grid.

It is, to say the very least, no longer difficult to find photos of mundane things arranged in that format. But because of the nature of Ohara's experiment, which required and extended a great deal of trust and curiosity to the people that participated, and because there was not yet the technology to make this sort of image ubiquitous or the capacity to make it into something that turns into money, it feels not just different, but new. Not because it is new, which it isn't, or because encountering these kinds of photos in this kind of arrangement is new. It is maybe more accurate to say that they feel fresh and vital, that the images pop with personality and life beyond any formal accomplishment or actual significance; they feel, that is, like pictures taken by people of their lives, for the sake of sharing whatever they found worth sharing, or just for the joy of doing it. It is the nature of social media, both in the attention-specific incentives it creates for the people that use it and in the all-devouring one that guides the companies that run it, to introduce artifice into this sort of imagery—every participant is, to some extent, managing their own brand and engaging with an audience whose attention they've set out to win. It can still be fun, of course, but it is unmistakably what it is, and for what it's for.

But if social media's incentives—the ones inherent in making everyone feel and act a little more famous, and the ones undergirding its variously sociopathic algorithms—seem to sit somewhere near the center of this current moment of national derangement, the wish to connect upon which it is all leveraged is fundamentally human. The incentives of social media push users forward and further apart, and out onto a horizonless battlefield of competition and unease; as individuals, in that strange combat, we are as doomed and paranoid as any of the '70s film protagonists I spent last winter watching themselves smash themselves against all those corrupted edifices.

Contacts, in the way it pulls all those small moments from small lives into a humane collective effort—the exhibition sprawls across a long room on the museum's third floor, the images on the contact sheets small enough that viewers need to lean in close—makes for a bracing and reassuring corrective to all that overbearing cynicism and dread. If you know what was happening in the United States between 1974 and 1976, you know what the world of Ohara's collaborators was like; if you look at what came together through their work, you can see how they survived it, and who they survived it with. "The camera was passed one hundred times, producing one hundred contact sheets," Ohara said in 1976, when he closed the project down. "These contacts represent one photograph."