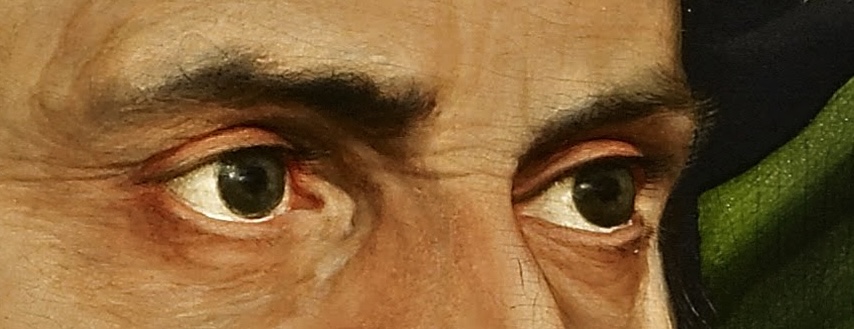

The eyes got me. Sir Thomas More by Hans Holbein the Younger isn't the brightest, or the largest painting in its room—it might be the smallest—but it's easily the most striking. It called to me from the next room over at the Frick Collection in New York, where it's hung since that tasteful robber baron purchased it in 1912. Here is something that speaks to me in that insistent way that few paintings have.

More is a man of middle age, sitting in three-quarters profile, staring intently off to our right. He is surrounded in earth tones, red velvet and black satin in front of green drapery. He clutches a book and wears a wedding ring, signs of his intellectual and domestic life. There are things that would draw the eye in a lesser work: Jonathan Lethem said, of the effect Holbein is able to pull off depicting that velvet, "that sleeve should be illegal." But it's the eyes that dominate. Of a rich grey that somehow resists being umbral, they are set in a lightly lined face that speaks to challenges met and still to come. If I knew nothing of Thomas More the person, I would see someone prepared to face an uncertain future.

But of course I knew Thomas More. Everyone knows Thomas More! Churchman, statesman, scholar, martyr. Utopia. A Man for All Seasons. Catholicism's strongest soldier, fighting against first the theology of the Reformation, then the realpolitik. Executed after refusing to allow Henry VIII to annul his first marriage. I think he was an answer on a seventh-grade history quiz I had.

Except. Do I really know Thomas More? Those are actions and works, not the man. This is how we know almost every figure from history: through their actions, with almost nothing of the self. Here is where art steps in.

More sat for Holbein's portrait in 1527, and looking at the painting in 2025, there I was, in the room with them. I saw a handsome man, exuding confidence. A composed firmness, perhaps except for very tired eyes, eyes that have seen tribulations, but undimmed for it. None of these impressions are accidental. Holbein, like any painter, did not merely reproduce what he saw, but made choices, meant to convey something of the person beyond the image. When I react to those choices, I am in dialogue with the painter, as he was in dialogue with his subject.

Transfixed by the eyes: bright, intelligent, penetrating. An insistent clarity of purpose. I feel as if I know more of the man Thomas More from this than any number of his deeds from a history book. Here before me is a person. Hilary Mantel speaks directly to the man in the painting:

"[A] vulpine genius. ... You are engaged, vital, ready to smile or snap out an impatient remark. Intellect burns through pale indoor skin, like a torch behind a paper screen. Concentration has furrowed your brow, the effort of containing multiple ironies."

It's always the eyes, isn't it? Those focal points of paintings that transfix then linger in the memory. Saturn Devouring His Son, the whites of the eyes telling of madness. Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan, the whites speaking to the brief and too-late reclamation of humanity, amid and after terrible violence.

Pareidolia draws our gaze to the eyes first, because those are the key that unlocks a person's mood, their intentions. It's a survival mechanism, really. The same things can happen when viewing a painting, as if the subject will offer us some glance, some wink, some Rosetta Stone that unlocks the person. But not every painting, and I don't quite understand the mechanics behind it—how some trick of lighting or body language or composition makes a portrait like Thomas More freeze me in place while I walk past others without a second glance. It is not necessarily realism—Goya's Saturn is not photorealistic—but an artistic conveyance of something real. Something as tangible, perhaps, as the visibility of an inner life glimpsed in the eyes. And there is nothing so tangible in the world as an emotion one has felt before.

I have spent time thinking about why it is that this painting affects me in a way that usually only literature does. Fiction, I usually think, is the widest and clearest window onto a soul.

That James Baldwin quote is overused, but understandably so because nothing more true has ever been said:

"You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who ever had been alive."

"An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian," Baldwin continued. This is what it's like to be human, the best books say. Paintings too. In Thomas More's eyes, I see a life and not just a man.

Here at the Frick, in the most literal sense, the story continues beyond the frame. Within Thomas More's line of sight, perhaps even the target of his gaze, is another man. The man who sent More to his death.

Thomas Cromwell, I feel like I know intimately. This is entirely thanks to Hilary Mantel, whose Wolf Hall and sequels are an achievement of historical fiction. Cromwell, known by his deeds, was long one of history's villains—a conniving, social-climbing, Machiavellian figure who served as Henry Tudor's attack dog, and crushed all in his path on his way to becoming the most powerful man in England. Mantel portrays not a different man, but a deeper one: a self-made man, loyal and protective, driven by genuine zeal for social reform. Mantel's Cromwell is brought to life by imagination but no less alive for it. He is just as alive as Pierre Bezukhov or Atticus Finch, and perhaps even more so for being real. When Mantel's Cromwell is wracked by self-doubt, a reader is in dialogue with the historical Cromwell—it is a thing we have felt, and we know that he felt, because he was human. Holbein's Portrait of Thomas Cromwell is less immediately commanding to me than More, hanging opposite him across the hearth, but feels more like encountering an old friend.

The man, yes, but the painting itself as well—Holbein is a character in Mantel's books, and Cromwell sitting for and eventually viewing his own portrait is an ongoing storyline in Wolf Hall. It is symbolic, that the son of a blacksmith has risen high enough to be painted by this visiting master painter. And, even more than his political victory over More, and More's execution, Cromwell's first viewing of the portrait is the emotional centerpiece of the novel, representing his own ignorance of how he is viewed by the world at large.

It is a relatable moment to anyone who's disliked a photo of themselves. Cromwell views the painting of himself—hunched, withdrawn, scowling—and is shocked by what he sees. His son is not.

When he saw the portrait finished he had said, 'Christ, I look like a murderer'; and his son Gregory said, didn't you know?

Holbein's Cromwell is not a looker (though I'm not sure his More would be any more pleasant to grab a drink with). The painting is darker, drabber, flatter. More's velvet sleeves leap off the canvas, begging to be caressed; Cromwell clutches tightly a piece of paper. More's background tapestry leaps with texture, his elaborate gold chain speaks of eminence; Cromwell wears a simple signet as his sign of office. More is clear-eyed and alert; Cromwell is beady-eyed and heavy-lidded.

The museum accounts the differences in style to Holbein's evolution as an artist in the five years between pieces. It is impossible for the viewer, however, not to take the two in opposition. At the time the latter was composed, Cromwell was ascendant, and More just a couple years from the headman's ax. “It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” Todd Oakley wrote in Do Pictures Stare? It is tempting to view this juxtaposition as Holbein, who knew both men well, making his own subtle comments on the principals of this political rivalry. Even now the artist speaks to the viewer.

The positioning of the two portraits is no accident, of course. The two men have been linked in history from the moment a triumphant Cromwell brought about More's death, then met his own just five years later, after a rapid fall from power. But it was Frick, purchasing Cromwell three years after More, who brought the works together so the two could continue forever their ongoing debate on the source and limits of temporal power.

The effect is a heady mix of history and fiction, past and present, literature and art. Everyone is in dialogue with everyone else. When I view Holbein's Cromwell, I am being spoken to by Mantel's Cromwell, and both or neither are Thomas Cromwell himself. I overhear snatches of whatever Holbein said to Mantel, her own interpretation deeply informed by this very painting I stand before. There are even side chats with objects in the painting. The prayer book on Cromwell's desk—the exact very book itself!—was located in Trinity College Library just two years ago. Nearly 500 years later, the dialogue continues.

In her essay on the provenance of the two Holbein portraits, Penelope Rowlands wrestles with her impression of Cromwell the painting being in opposition to what she knows of Cromwell the Wolf Hall character. "He looks wary, hunted, alone. 'No one has ever suggested that it is an endearing picture,' his biographer Diarmaid MacCulloch has written. How could one? Still, there’s a hint of vulnerability here, something rueful in Cromwell’s expression. He seems conflicted." This self-doubt of our own impression is a form of dialogue too, one that probably gets us closer to the truth. History and men aren't neat things. In this lacuna between what we see and what we know is a pleasant frisson that for the sake of simplicity we can call art, where we can look them in the eye even if they won't look back.