I was really excited to see Twisters. Excessively excited. I was more excited to see Twisters than I was to see Twister almost three decades ago. That film came out in May 1996; Mission: Impossible came out later that same month, and Tom Cruise trumped tornado. I don’t actually remember being that bothered about any of the disaster movies coming out at the time. They all seemed to kind of be B-movie rentals—Dante’s Peak, Volcano, Deep Impact—or they were box-office events like Titanic and Independence Day, which I also didn’t care about. There were too many good indies (though somewhere in there I got really hyped up about Deep Blue Sea, but that had a big shark in it). Now, I will take almost any disaster movie. I will take even a minor disaster movie over Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes or Furiosa or Bad Boys: Ride or Die. I couldn’t wait to see A Quiet Place: Day One, for example, even though that one is technically about aliens.

Twisters seemed really excited about itself, too. Everyone in it seemed really excited. It was like being at a terrible party where everyone keeps going on about how fun it is in order to bring up the mood. I was sitting next to my brother, who I had dragged to see it, and who had admittedly started to get excited himself after seeing all the good reviews. The reviews were surprisingly good. That has never really been an indication of anything, but when you want to see something enough, you are willing to fall for it. We fell for it. And then we just kept looking at each other throughout it like: Why is this ... kind of ... boring? Other people must have felt this way. People kept getting up to leave—to go to the bathroom, to get snacks—but not in the kind of hurried way you do when something is gripping. I felt like one guy left for a good 15 minutes. I felt like all this coming and going, if perhaps more indicative of how people watch movies now, was definitely not a sign that Twisters was riveting. Say what you want about Longlegs, but for whatever morbid reason, people were glued. And that wasn’t even an action movie.

Let’s see if I can remember this plot, such as it is. Daisy Edgar-Jones, with the same muted energy she brought to Normal People, comes up with a way to reduce the intensity of tornadoes, but to get a grant she needs to prove she can do it. So, she takes her team—Kiernan Shipka (also in Longlegs!), a guy I couldn’t place for ages until I remembered he was the gigolo in that Emma Thompson movie, and some guy I’ve never seen before—but something goes wrong, the tornado overtakes them, and everyone dies except DEJ and the dude in the measuring van (Anthony Ramos!).

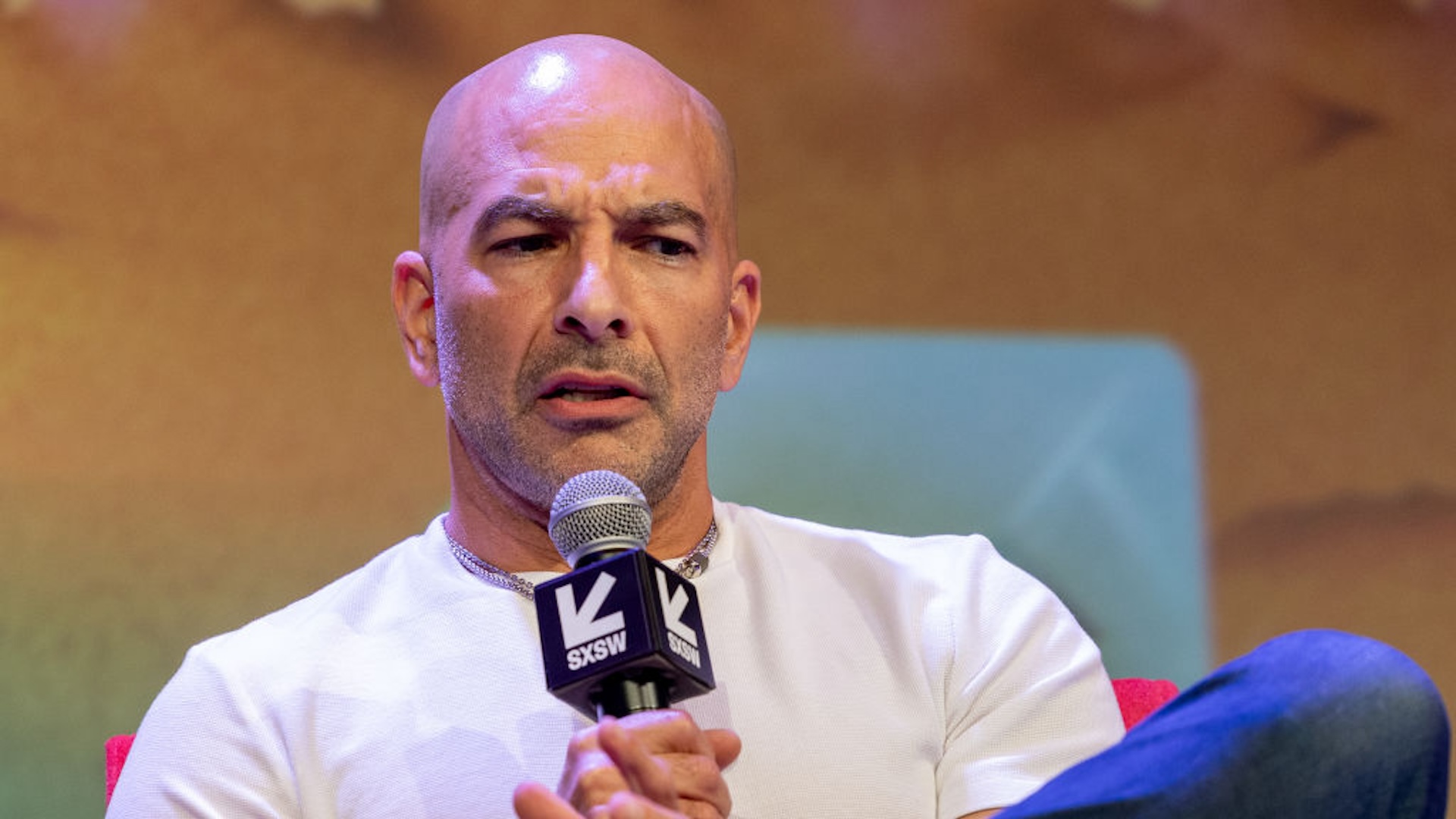

Fast-forward several years and DEJ is languishing at a desk job that actually sounds kind of awesome, at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in New York. But Ramos is back with a new haircut! He has now secured massive investment for his tornado scanner and the only person he can think of to test it out is DEJ, even though their track record together has a literal body count. Of course she says yes, because this was what she was born to do. But then they are in Oklahoma and Glen Powell shows up because he has a storm-chasing YouTube channel and that face. Along with him is a team of misfits with a cowboy attitude. Obviously, they are the good guys—turns out Ramos is working for a real-estate villain, while the YouTubers share their profits with tornado victims—and DEJ ends up with them. All you really need to know about this tornado movie is that not even Powell, the charisma planet, can save it.

It can be hard to pinpoint why a movie feels boring; it’s usually a bunch of elements not quite landing. In this case, the main problem seemed to be that the camera just wasn’t very interesting. This is the kind of film where you expect to be thrown up and down and in and around, and just generally for everything to be up close and hyperkinetic. A few years ago, Twister director Jan de Bont explained that the reason action movies started getting interesting around the time he became the cinematographer on Die Hard (before he went on to direct Speed and then Twister) was because the industry moved away from what he called “static action.” “We could have those kinds of moving, roving cameras, which gave it a new kind of energy, as if the audience was actually present at the time. That was our goal,” he told Vulture. “I like to put a camera right where the audience would have liked to have been if they were there. It immediately will be better, almost instantly.” This new approach also involved integrating dialogue into the set pieces, energizing the script with improvisation and cutting out as much exposition as possible to avoid stagnation.

It's telling that Lee Isaac Chung’s pitch to direct Twisters involved intercutting footage from Twister with Minari, his Oscar-winning semi-autobiographical meditative drama about an immigrant family in Arkansas, specifically a scene where the family’s mobile home is threatened by a tornado. “I wanted the film to have sober moments where we really look at destruction and we try to recreate it in a very realistic way,” Chung told Letterboxd of Twisters. “We also look at those moments with a bit of silence and reverence.” I think this may have been the bigger issue with the film, that it is an observant Twister, rather than just Twister. The camera, the dialogue, even the music felt oddly unintegrated, like it was all passively operating alongside the events. And the engine of the film, DEJ wanting to help people, didn’t quite rev. It was also often hard to tell how much Chung was playing off middle-American tropes (see Powell in that skin-tight white T-shirt in the rain) versus falling into them (see that gratuitous rodeo scene).

This seems of a piece with the film purposefully not mentioning climate change (while openly adopting the neoliberal message that technology can save us). Chung told CNN that he “wanted to make sure that we are never creating a feeling that we’re preaching a message, because that’s certainly not what I think cinema should be about. I think it should be a reflection of the world.” But the world is currently experiencing some of the worst weather events in history because of climate change. I don’t know how not mentioning that in a $155 million movie that was positioned to have the biggest opening of any disaster movie ever is not itself a message.

Despite all of this, I kept watching Twisters not just because I was maybe going to write about it, but because there were small bursts of levity in all that haze. The way Sasha Lane, when she is first introduced as part of Powell’s team, basically says “What’s up?” a bunch of times, like she’s having a good laugh at having found herself in a tornado movie. The way Brandon Perea, also part of Powell’s team, with his mustache and his muscles and that accent, effortlessly draws you in the way he did in Nope. But the biggest draw, out of nowhere, was Maura Tierney, playing the neglected mom to DEJ—her wry expressions, her pouty lips, the way she walked and delivered every line, like she could turn around this whole thing if she wanted to—she alone almost makes Twisters worthwhile. Put Tierney in everything. The sweetest surprise, besides late Twister star Bill Paxton’s son as a petulant motel guest, was Paul Scheer as an aggro airport attendant. His exasperation at an immovable Powell—taking a dramatic pause at the end, while trying to decide whether to go in to get DEJ—served as a kind of surrogate catharsis for my frustration.

These bits also made me wonder how much better a lighter version of this film would have been. Apparently, original Twister star Helen Hunt pitched a sequel not too long ago, co-written with Rafael Casal and Daveed Diggs, about storm chasers from an HBCU, which recalls de Bont being inspired by grad students at the University of Oklahoma. It would have been fitting, considering Twisters exists very much in the shadow of Twister. More than the film itself, it’s that time in cinematic history that Twisters seems intent on recreating, a time in which a disaster movie could be helmed by the guy who made Speed and be co-written by the guy behind Jurassic Park and star veterans like Hunt and Paxton. Twister was the second-highest grossing film of 1996 and apparently helped turn May into the start of the summer blockbuster season. In its distant wake, the industry keeps tallying Twisters’ numbers, seemingly in the hopes that it can travel back in time. This is how you get articles with headlines like "They Don’t Make Disaster Movies Like This Anymore," "Twisters Proves We Need To Bring Back More ’90s Disaster Movies," and "Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success."

“From an economic standpoint, of course it matters whether Twisters—which is expected to bring in $50 million to $55 million when it opens in North America this weekend—is a hit or not,” wrote Stephanie Zacharek in Time. “You can hate the monolith known as the industry, but the sad reality is that anyone who cares about seeing movies on the big screen has a stake in that industry’s survival."

Twisters is a “fact of it” movie: The fact of its existence is the point, whether it is good or not. There are a lot of these now: movies attempting to recapture something the current landscape cannot sustain, movies which carry almost the weight of the entire industry, as if anything can live up to that, as if anything can be good while trying to do that. As Powell says in the movie, in a line which sounds powerful but is in fact the opposite, “We don’t face our fears, we ride ‘em.”