In January 1955, a lifelong football fan approached Lou Spadia, the general manager of the San Francisco 49ers, with a peculiar request: Would his players like to participate in a science experiment at an atomic research lab?

It wouldn't take much, the fan explained—just some radioactive material inside the players, who would then undergo a physical examination. The end result, he promised, would be "of mutual benefit and undoubtedly of interest to" Spadia, team owner Tony Morabito, head coach Red Strader—and to science.

The 49ers had just finished their fifth season in the NFL, and though they'd missed the playoffs for a fifth straight year, they were one of the league's top draws and seemed on the cusp of something big. Joe Perry, the first man to rush for 1,000 yards in consecutive seasons, had just been named the league's first Black MVP. Perry and perennial all-pro Hugh "The King" McElhenny, a celebrity since high school, lined up in what a team PR man had dubbed the "Million Dollar Backfield." Pure gloss, since no player back then made even six figures, but the flack was onto something: Perry, McElhenny, and teammates John Henry Johnson and Y. A. Tittle are all in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

This helps explain why Spadia's correspondent, a Navy physician named Albert R. Behnke Jr., was interested in the 49ers. It doesn't explain why Spadia, Morabito, and some players evidently agreed. Within a couple of weeks, Behnke had "completed arrangements" for the 49ers "to serve as subjects" in a nuclear-medicine experiment, as a colleague at UC Berkeley reported in one of the four surviving letters that outline the situation.

Behnke had been in the news a few years earlier, when he reported the failure of an unorthodox experiment: feeding sailors in the Pacific "large quantities" of garlic in order to ward off mosquitoes. But the 49ers likely knew their man from his groundbreaking work analyzing the physiques of pro football players.

The 49ers were almost certainly the most high-profile participants in a wider, decades-long research program at the U.S. Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, a specialized "atomic defense" outfit headquartered at a major naval shipyard in San Francisco from 1946 to 1969. But they weren't the only ones: Scientists there exposed at least 1,073 people to potentially harmful doses of radiation in at least 24 experiments and technical exercises. (The former shipyard, a profoundly polluted EPA Superfund site that generations of activists say has poisoned the historically Black neighborhood where it's situated, is now part of the biggest real-estate redevelopment project in San Francisco since the 1906 earthquake.) All this, plus the 49ers' involvement, is spelled out in government documents, scattered across the country, that I spent years combing through for an investigative series you can read here.

Behnke did not mention he might also be able to judge which 49er was most likely to survive a nuclear attack. As a U.S. Department of Energy researcher summarized decades later, his research included studying "athletes and the physically fit in order to determine probable survival in the case of nuclear war."

A direct collision of pro football and the nuclear enterprise was unlikely if not for Albert Behnke, known today as "the father" of two distinct fields—body composition and modern diving medicine—and one of the more interesting Americans you've never heard of. Scientific literature concerned with keeping submarine crews and scuba divers alive, and with athletic performance and physiology, are full of references to his work.

The genius researcher was also a natural athlete. He played football at Whittier College in the 1920s and would carry the 200-pound bulk of a leather-helmet–era lineman through most of his life, even while swimming in the open Pacific, with his wife deployed on the beach to watch for sharks. He also performed in the clutch, saving people from drowning on two occasions.

Behnke published research into his eighties, three decades after he retired from the Navy. He stuffed the family apartment, a modest two-bedroom affair in San Francisco's Pacific Heights, floor to ceiling with scientific journals, books, and correspondence—two literal tons of which were donated to Duke University after his death in 1992, his daughter, Alice Johnson, told me. But if it was the weekend and it fell between September and December, the television was on and tuned to football. "There was always a game on," Johnson recalled.

He also applied what he learned to practical scenarios. Before Detroit mandated seatbelts, Behnke lined the back of the family car with styrofoam blocks covered in fabric, providing some protection for his daughter from injury in a collision. You could say Behnke was a visionary who predicted side air bags, or you could interpret this as Johnson does: It was a product of her father's lifelong obsession with survival.

The son of Quakers who moved west from Illinois to the Southern California orange groves, Behnke accepted a commission in the United States Navy following graduation from Stanford Medical School in 1929. He became fascinated with diving while posted to a submarine group where sailors were experimenting with escape techniques. After one man collapsed and died during a training exercise, Behnke wrote the Navy's Surgeon General, presenting an analysis of what went wrong and potential solutions.

Impressed, the Navy sent him to study applied physiology at Harvard, where he first wrote his name into the textbooks in 1935, identifying nitrogen intake as the cause of the bizarre combination of intoxication and euphoria afflicting divers using compressed air. A few years later, Behnke and a colleague discovered you could treat the condition, now called nitrogen narcosis, using pure oxygen in a pressurized setting.

The chance to put theory into practice came in May 1939, when an experimental Navy submarine called the Squalus partially flooded and sank in 240 feet of water off Portsmouth, N.H., stranding 33 men on the ocean floor in a dead boat. Lieutenant Albert Behnke was a member of the rescue team rushed to the scene amid an intense national spotlight. All hands were saved.

Behnke's research made the Pacific submarine fleet deadly effective, but he still found time for football. In 1942, after studying 25 players as part of a wider cohort, Behnke and a colleague devised a value for a human's "specific gravity"—a measure of their density relative to water, that also quantified whether they were obese and ought to be rejected for military service.

Advances in this discipline, "body composition," were enormously significant for medicine. Quantifying what was inside a human—how much water, how much fat, how much muscle, and so on—meant quantifying what was wrong, and knowing, with some certainty, how to solve it.

It was this work that won Behnke worldwide admiration. He would study human physiology for most of the rest of his life. But a sobering postwar assignment to occupied Germany, where U.S. intelligence tasked him with studying the "severe malnourishment" affecting the civilian population, left a very deep impression.

"From 1945 to the middle of 1948," Behnke later wrote in his report from Germany, "one saw the probable collapse, disintegration, and destruction of a whole nation," a dire situation packaged with "physical and psychic trauma unparalleled in history."

If that sounds like sympathy or apologia for Nazis, consider the facts as a clinician would: The conquering Red Army committed mass rape as it marched on Berlin, sexually assaulting an estimated two million German women. Roughly three million German men were in Soviet captivity, 1.1 million of whom would die before their release years later. A severe drought followed the first brutally cold postwar winter, triggering a famine. According to Behnke's research, Germans' daily caloric intake dipped to almost one-third that of Americans—a diet so meager that the average weight of a German in 1947, 131 pounds, was only six pounds heavier than that of the emaciated veterans who survived Soviet captivity.

Behnke and a colleague lived on the Germans' meager ration allotment while traveling the country. He talked to everyday people and interviewed Heinz Guderian, the panzer general who pioneered blitzkrieg. In 1958, Behnke delivered a lecture on his findings:

The paralyzing, enforced idleness on a people possessing exceptional technical ability, and capacity and desire to work, amidst a setting of ruin, the disruption and at times paralysis of transportation, the destruction of historic shrines and national monuments, all these contributed to the apathy and apparent hopelessness of any economic or political future for Germany.

Of equal importance to the physical stresses and injuries were overwhelming psychic depressant and disintegrating factors centered on the humiliation of defeat, the world-wide censure and opprobrium, anxiety over the fate of prisoners, outrages committed against women and the many retaliatory acts of brutality which have been visited on the conquered.

Yet, he added with obvious admiration, "irreversible physical and psychological breakdown did not occur." In fact, certain metrics improved.

Since nobody could overeat, there was a "remarkable decline" in "luxus" afflictions such as diabetes and hypertension. As for mental health, Behnke noted "a decrease in psychoneurotic disorders and an abrupt fall in the suicide rate." He chalked up this resilience to "the primitive urge to survive and the struggle to live," and, less scientifically, to a national character built up over many centuries.

The Germans had clung to "the sustaining forces of family life and of tradition in a land that had been overrun and conquered many times during past centuries," he wrote. And that "acted to give assurance that somehow there would be survival."

But could Americans, a much younger society, still unbeaten and unbowed, hope to repeat the Germans' "survival and revival against seemingly hopeless odds," were the bombs to fall?

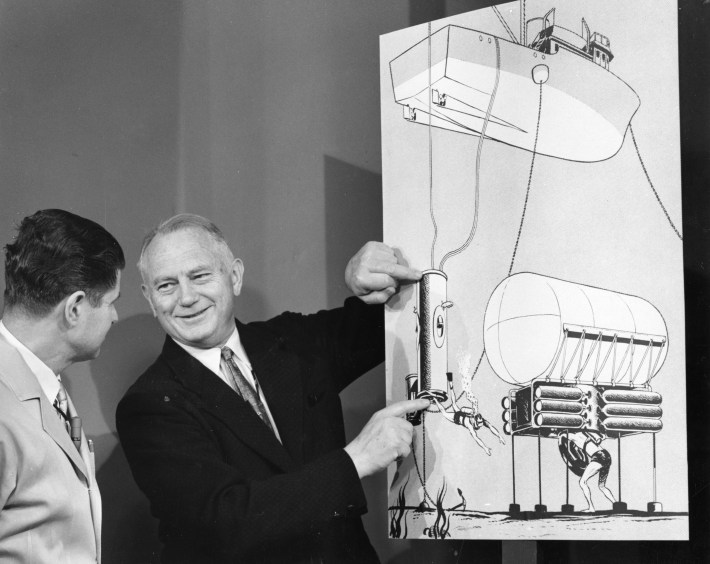

For someone in the United States Navy, there was no better place to find an answer than the service's dedicated atomic research lab. And so for the final act in his Navy career, in 1953, Behnke reported to the U.S. Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory in San Francisco's Hunters Point. As the lab's top physician and "radiological medical director," Behnke continued researching physiology, but with a new toy: nuclear medicine.

A common diagnostic tool today, the practice involves absorbing just enough of a radioactive isotope of an element abundant in the body—the hydrogen in water, say, or potassium—to literally "light up" problem areas like tumors in subsequent scans. For Behnke and his colleagues, the isotopic elements made determining vital metrics like total body water or blood volume quick work.

Most of the radiation doses involved in nuclear medicine back then were low. According to the lab's Atomic Energy Commission materials licenses, someone drinking tritiated water and receiving injections of radioactive chromium—as Behnke proposed for the 49ers' "special examinations"—might absorb a dose of between 0.1 to 0.2 rem per procedure. A rem (Roentgen equivalent man) is a unit of measurement denoting the amount of radiation absorbed by living tissue. For comparison’s sake, the EPA estimates Americans' average annual radiation dose to be about .620 rem—half that from the environment.

Behnke appeared eager to use these techniques on himself, judging by lab reports that note a subject with the initials "ARB." He might have emphasized that to Spadia, the 49ers' general manager, whom he wrote on Jan. 6, 1955.

The 49ers must have been keen, as Behnke "completed arrangements for the professional football players (49'ers) to serve as subjects here at the Laboratory," by Jan. 10, wrote UC Berkeley's Bill Siri, Behnke's collaborator and another brilliant scholar-athlete. Two players were going to do a "trial run" first, with—hopefully—more to follow.

"We are ready to take on the 49'ers any time at your and their convenience,” Siri wrote Behnke on Jan. 12. There were some details to iron out—exactly what Behnke wanted measured, how much the lab should offer the 49ers in terms of compensation—but it was clear working with the NFL team was an exciting prospect. "I sincerely hope you can persuade as many of these men as possible to participate in this program," Siri added. "For our purposes, they are an extremely important group."

The 49ers didn't help Behnke much. As it turned out, the best athlete that Al Behnke ever saw was a woman: the long-distance swimmer Florence Chadwick, with whom the Navy man struck up a warm and lasting correspondence as she prepared to be the first to swim across the San Juan de Fuca strait between Washington and Vancouver Island. Someone who could survive cold water for 10 hours at a stretch was of more use to the Navy, where sinking was an occupational hazard, than a football player.

It's also not entirely certain the experiment happened. No final report ever emerged during a government-wide search for human radiation tests in the early and mid-1990s. Behnke had been dead for two years when a Department of Energy researcher contacted Siri in November 1994.

Then 75 years old, Siri "did not remember anything about the experiments with 49er football team," the DOE’s Lori Hefner wrote in a brief report in 1994. To jog his memory, Hefner sent him copies of his 40-year-old letters to Behnke. Siri found them "interesting," but they didn't shake anything loose. "It was so long ago, and so many studies were done," he said.

A few weeks later, Hefner reached a longtime lab researcher named Ed Alpen, who'd worked directly under Behnke while at the Navy lab. Alpen was a big name himself. He'd received a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship, directed a U.S. national laboratory, and held professorships at UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco. And he was sure of things.

Alpen "knows the experiments took place, because he was in the room when they were done," Hefner reported. In his recollection, the 49ers received their radioactive doses at Siri's lab but went to Behnke and Hunters Point "for the weighing portions of the experiment."

I called and emailed the 49ers a few times to see if there was anything they knew. I was not surprised to never receive a reply. I did manage to contact former 49er Hugh McElhenny's family a few months before he died in 2022. His memory was poor, and he did not remember anything about any experiments, I was told.

Alpen died in 2006 of brain cancer at age 84.

Neither Behnke nor Siri ever published anything specifically related to the 49ers' visit. The DOE noted some "references to professional football players" in a few journal articles, which could have been Behnke's earlier groundbreaking work in Washington. It could also have been Al Behnke's understanding of the body, further informed by the pro football players that Alpen remembered marching into his lab.

Alice Behnke Johnson doesn't remember her father talking much about nuclear bombs or what might happen after an attack, she told me when we spoke by phone last fall.

Part of the reason could be the fact she was an infant when he retired from the Navy and then went onto other things. One of these retirement gigs was consulting for the Bay Area Rapid Transit's Transbay Tube, the concrete tunnel sunk into the muck between San Francisco and Oakland. (Among the privileges of the job was leading friends and family on miles-long walking tours into the tunnel, where workers sweated at familiar high pressures.) Another, she guessed, was that nuclear war was sort of like an earthquake: just another mortal threat that Californians, or Americans of the nuclear era, learned to live with and then didn't spend too much time agonizing over.

I have my own personal theory: Al Behnke didn't talk about it much because Al Behnke, a jovial optimist, didn't like what he found out.

After learning what he could from the 49ers, Behnke delivered a lecture on nuclear war survival in June 1958. He did not rate most Americans' chances, bemoaning how the country's runaway economic success and high standard of living had created a class of idlers, alcoholics, and the chronically ill, all reliant on others. They would be terrible burdens in an attack scenario, in his view, when any atomic survivors would have to seek refuge in underground shelters for long periods of time. They would have to exit and walk long distances to find the food and water to sustain them, avoiding or surviving hazards like fallout along the way. To maintain order and morale, they would have to possess a focus bordering on religious zealotry.

In fact, about the only group of Americans Behnke felt stood a chance were the self-sufficient, devout, and teetotaling Mormons. As for the rest of us, not only did most Americans lack the physical capabilities for these labors, they didn't give a shit. Despite clear and constant warnings of looming atomic disaster, a "national lethargy and indifference in defense matters" had afflicted the country, with "overconfidence, defeatism, and blatant selfishness" overriding any survival impetus, he warned.

He went on to quote with disdain an unnamed "prominent civic leader and planner of New York City." This man had dismissed the idea that "sane" Americans would ever "support a fantastic national underground escapist program" that would cost something close to double the annual defense budget. "We shall have to live with this problem somehow or other. We are not going underground. We shall not evacuate and disperse. We shall not change our way of life."

Instead, as Robert Moses wrote in a 1957 article published in Harper's, "the problem should be up to the established Department of Defense, which is supposed to protect us against attack and launch the counter-offensive."

As it usually did, America followed the master builder's demands. At the expense of nearly everything else, the U.S. spent vast sums on the nuclear triad—and is still spending, with $51.5 billion splashed on the arsenal in 2023 alone—in the hope that mutual assured destruction would discourage a first strike, the doctrine radical journalist I.F. Stone called "the ultimate delusion of the atomic era."

That left anyone looking to figure out nuclear survival on their own: digging their own shelters, stockpiling their own food, as survivalists in the elite class do today. As Al Behnke concluded: "The training and material preparedness to cope with disaster situations will be the responsibility of the individual himself."