Cleveland loves to immortalize its sports heroes. The street behind the left-field bleachers at the Guardians' ballpark was renamed for Larry Doby in 2012. The Browns' offices in Berea are on Lou Groza Boulevard. There are parks named for Luke Easter, a Negro Leagues slugger who played for the Indians, and Mel Harder, a longtime pitcher and coach. (Harder's park is also his final resting place. His ashes were scattered there following his death in 2002.)

But Cleveland immortalizes its sports villains, too. Art Modell has an Ohio law named for him.

The law was passed in 1996, a year after Modell announced his intention to relocate the Browns, which he'd owned since 1961, to Baltimore. Put simply, it states that the owner of a professional sports team "that uses a tax-supported facility for most of its home games and receives financial assistance from the state or a political subdivision thereof"—which, in this day and age, means almost all of them—must either reach a settlement with the county or municipality before relocating, or offer the team for sale to local interests who ostensibly would not relocate.

Modell and the city of Cleveland ended up reaching what remains a unique settlement: The team would relocate to Baltimore and become the Ravens, but the Browns' name, colors, and history stayed in Cleveland, where they would be used for an expansion team no later than 1999. This settlement was not a product of the law; it was a product of the possibility that otherwise Modell would be sued into oblivion for breaking the lease at Cleveland Municipal Stadium.

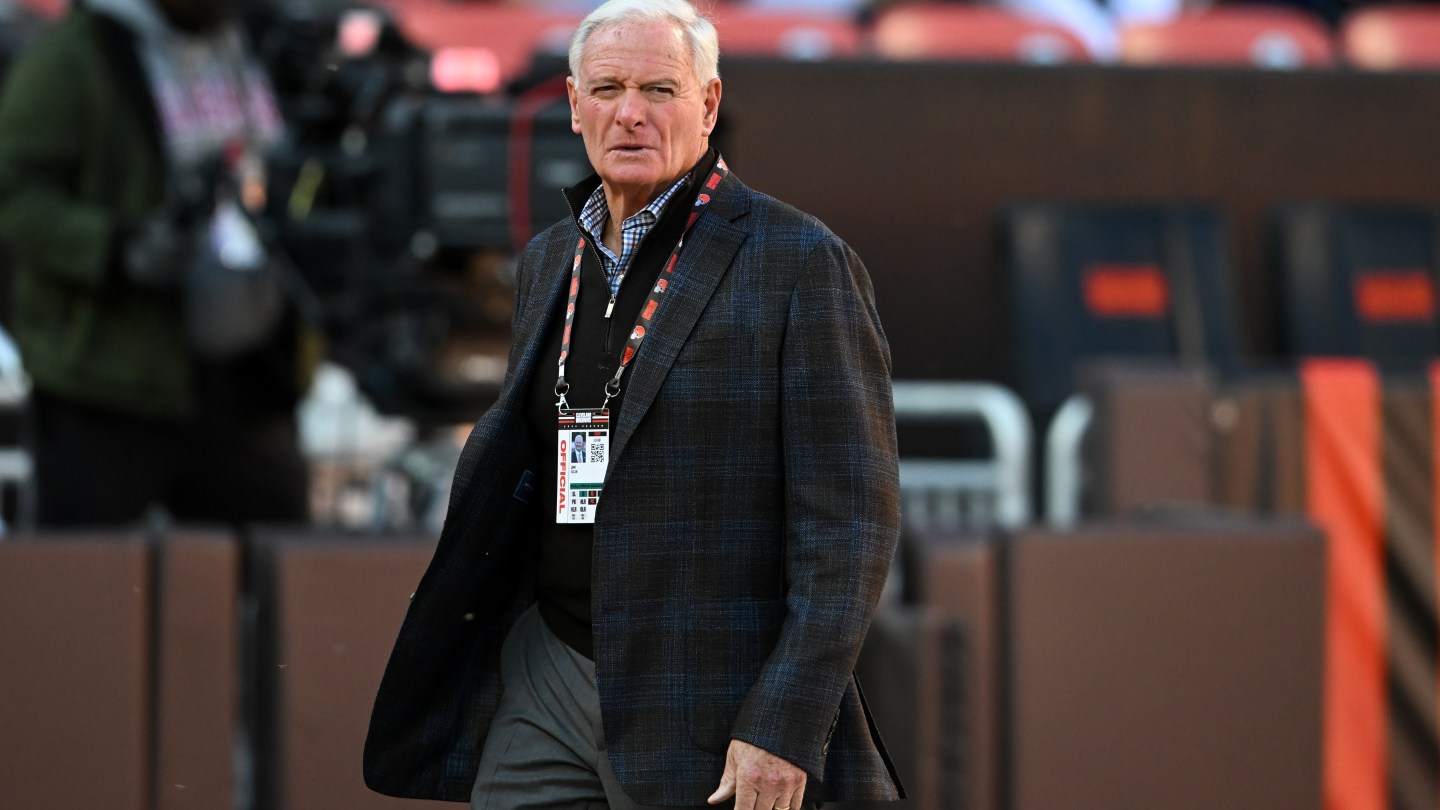

Local politicians are considering invoking the law as the city has been fighting to keep the new Browns not from moving to another market entirely, but from leaving the city limits for a domed stadium near the airport, in a suburb called Brook Park. It's the latest salvo between the Browns' owners, Jimmy and Dee Haslam, and the region the team calls home.

The Haslams' lawyers have questioned the constitutionality of the law, and have preemptively sued the city of Cleveland in an attempt to prevent its use, but it has been invoked once before: when MLS's Columbus Crew had one foot out the door for Austin. Instead, Austin got an expansion team, and the Crew stayed in Columbus—at a new stadium—and got new, local ownership: Jimmy and Dee Haslam.

In 1996, Browns fans were trying to figure out how they'd spend their Sunday afternoons. Crew fans were looking forward to MLS's inaugural season, while construction on the league's first soccer-specific stadium waited to get underway. And Dennis Kucinich was plotting a comeback.

Before he was a presidential also-ran, Kucinich's arc of power in Cleveland was parabolic. He was elected to city council when he was 23, and just eight years later, in 1977, he was elected mayor. The fall of the Boy Mayor, as he was called locally, was just as swift. His changes to city government so enraged the Cleveland mob—then in the midst of an internecine war so brutal that it gave Cleveland the nickname "Bomb City, USA"—that a contract was taken out on him. Kucinich threw out the first pitch at the 1978 Indians opener while wearing a bulletproof vest, with sharpshooters watching for trouble from the roof of the stadium. He was greeted that day with a cascade of boos, as his mayoral administration seemed to make one misstep after another, among them his firing of the city's police chief on live TV. Kucinich barely survived a recall in August 1978, but by the end of the year, the city had defaulted on its loans, in large part because local banks called in the loans to try to force Kucinich to sell Muny Light, the city-owned power company, to Cleveland Electric Illumination. (CEI would later become part of FirstEnergy, which has held its own illegal sway over Ohio government—and for a while was the namesake of the Browns’ stadium.)

Kucinich ran for re-election in 1979 and lost to George Voinovich. He made a few efforts to return to elected office in the 1980s, but he wandered the desert— figuratively and literally, with a move to Arizona. Eventually, he returned to Ohio, and in 1994 won a seat in the state senate. In 1996, Kucinich sponsored a bill to prevent what had happened in Cleveland the previous fall from happening in Ohio ever again: the Home Team Protection Act, quickly nicknamed for Modell, the local Public Enemy No. 1.

It was a winning issue. Kucinich was running for Congress that year. His Republican opponent, Martin Hoke, introduced similar federal legislation, the Fan Freedom and Community Protection Act. In fact, Hoke's bill would’ve gone a step further, mandating that a team's name and history stayed with a city if the team moved, and requiring expansion teams to replace teams that relocated. That bill died in committee.

Kucinich's bill was signed into law by Voinovich, by then Ohio's governor. Kucinich beat Hoke that fall to take a seat in Congress, and in 1999, the expansion Browns team started playing in a new lakefront stadium, on the site of old Cleveland Municipal Stadium. It would take two decades before the Art Modell Law faced its first test.

Lamar Hunt, aside from being one of the AFL's founders and owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, was a huge soccer booster. He owned the Dallas Tornado of the North American Soccer League and, when Major League Soccer started, bought in with the Columbus Crew, which started play in 1996 at Ohio Stadium. He financed the construction of a new soccer-only stadium, which opened near the Ohio State Fairgrounds in 1999. Hunt died in 2006, and in 2013 his family sold the team to Anthony Precourt, a San Francisco private equity financier. It wasn't long before Precourt started looking for a new stadium, and he felt that he could get one in Austin, Texas.

Fans in Columbus were aghast. Before the Blue Jackets began play in 2000, the Crew were that city's first major-league team since the Columbus Panhandles of the American Professional Football Association, a forerunner of the NFL. Much like with Browns fans a generation earlier, a grassroots effort sprung up to save the Crew, with rallies and protests, and looked like they'd be just as ineffective this time around, as Precourt appeared determined to relocate. But there was another weapon available to keep the Crew in Columbus.

The city of Columbus, joined by then–Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine, sued the Crew under the provisions of the Art Modell Law. Precourt's lawyers argued that the lawsuit was invalid because of MLS's unique structure as a single-entity owner of all the teams (as part of the defense, Precourt's title had changed from "owner" to "investor"), and that the law was unconstitutional: specifically that a state couldn't discriminate against interstate commerce, a power explicitly given to the federal government.

The lawsuit was dismissed shortly before an announcement that Precourt would be selling his interest in the team and buying into an expansion team in Austin. While the Art Modell Law hadn't directly stopped the Crew from leaving, it put up enough roadblocks that an alternate deal could be reached. It also meant that the law never had a chance to be litigated, leaving its constitutionality up in the air.

The Crew’s new "investors" were Jimmy and Dee Haslam, Tennessee natives who had first bought into the NFL as minority owners of the Steelers while that team restructured its ownership, and then bought the Browns when Randy Lerner put them up for sale in 2012. Among the terms of the Crew's sale to Haslam were that the team would get a new stadium, which opened in 2021 in Columbus's Arena District, not far from where the NHL's Blue Jackets and Triple-A Clippers play. The Haslams were viewed as a godsend in Columbus; the move was eyed a little more suspiciously in Cleveland, where abandonment issues abound to this day.

When the Haslams bought the Browns, they didn't completely reject the idea of a domed stadium, but serious consideration of the idea didn't start until this year, four years out from the expiry of the team's 30-year lease. At the owners' meetings, Jimmy Haslam said there were two options under consideration: a renovation of the current stadium, or a new dome built on a 176-acre site adjacent to the Ford plant in Brook Park.

This summer, the games began. On Aug. 1, Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb promoted a plan for a $1 billion renovation of the stadium downtown, with a city contribution of $461 million, a civic record for a stadium, and a new 30-year lease. That wasn't cushy enough for the Haslams, who, six days later, announced their own plans for a $2.4 billion domed stadium in Brook Park.

It should be noted that the Haslams are counting on public money for a new home, but while the city of Cleveland has promised a potential investment for a renovation of the existing stadium, there has been no such luck on a dome. Cuyahoga County officials and state legislators have already flatly said no. (And Hamilton County Commissioner Alicia Reese said that if a Browns stadium gets state funding, then a proposed Cincinnati Bengals stadium renovation—estimated around $1 billion—should too.) A great irony in all this is that the Haslams are asking for one of the largest public investments in a stadium project in American history the same year that the Browns are one of the worst teams in the league—and that their signature win came in a winter wonderland against Pittsburgh, a tableau that would be impossible to create in a climate-controlled dome.

Almost as soon as the Brook Park site became a possibility, Dennis Kucinich started bringing up the Art Modell Law. "My concern is they're just using Brook Park as a foil and they may be looking elsewhere, out of state," Kucinich told Cleveland.com. "This law protects the taxpayers wherever they live ... If the Haslams no longer want to be in Cleveland, then let a group of investors from Cleveland keep the team here. And again, nothing against Brook Park, but you know, this is a law that must be abided by."

Once again, Kucinich was in the political wilderness. When Ohio lost two House seats following the 2010 Census, Kucinich was forced into a primary against another Democratic incumbent. Kucinich lost and tried to remain relevant in politics. He was a contributor to Fox News, leaving the network in 2018 to run for governor. He lost in the Democratic primary, and in 2021 mounted a bid to become the oldest mayor in Cleveland history, 44 years after being the Boy Mayor. One of seven candidates in a non-partisan primary, he finished third, out of the money for the runoff election, which was won by Bibb. In that race, the Haslams donated to an anti-Kucinich SuperPAC.

Kucinich then managed Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s 2024 bid for president while Kennedy was running as a Democrat; they parted ways when Kennedy opted to run as an independent. Kucinich himself ran for Congress as an independent this year, challenging Republican Max Miller in a suburban Cleveland district that included Brook Park. Kucinich's campaign ads pointed out that the Haslams had donated to Miller's campaign while Miller touted a potential Browns move to Brook Park.

On Oct. 17, a frustrated Bibb announced that the Browns were moving to Brook Park. Kucinich urged the city to invoke the Art Modell Law, even going so far as to threaten a lawsuit himself, based on his status as a Cleveland taxpayer. But on Oct. 24, attorneys for Haslam Sports Group filed suit in federal court seeking declaratory judgment that the Art Modell Law is unconstitutional—making a similar argument that Precourt made in Columbus, claiming that the law is vague and violates the Dormant Commerce Clause.

On Halloween, the state government entered the fray: Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost filed a motion in federal court to intervene and defend the statute. The city has until Dec. 16 to respond to the team's filing.

Because the law has never been applied in court, there's no precedent to cite. But legal analysts seem to think it has small chance of success. Cleveland State University law professor emeritus Alan Weinstein said that the biggest consequence might be bad press for the Browns—which surely can't be much of a threat to the organization that gave Deshaun Watson the largest guaranteed contract in NFL history. Case Western Reserve University law professor Anat Alon-Beck said it would be a test of private property rights. "I think it's about property rights and whether they have a right to relocate or not," she said. "Are you going to force them to sell or is it just a right of first refusal? I think that's another thing that the court will have to evaluate."

There will definitely be a lot of attention on this case, and in another lost season for the Browns, the most interest the team has gotten in years might be in a federal courthouse where you can see the Browns' stadium from the upper floors. For now.