Over the course of nearly a decade, Gisele Pelicot of Mazan, France, was drugged and raped by her husband and as many as 83 other men he invited to do so. Presented with the option to prosecute the case privately, Gisele instead insisted on a public trial. Sophie Smith writes in an essay for The London Review of Books: “Her hope – and in this she is not alone – is that by publicising the behaviour such a society produces, the trial will be a step towards changing it.” The accomplices of Gisele’s husband, Dominique, variously admitted their guilt or rejected the use of “rape” outright. Several men repeated the line, “I am not a rapist,” with added justifications that Gisele must have known what was happening, that it was all a game, that she actually wanted the encounter to happen. “Liar, slut, loudmouth, killjoy: as is often true of rape trials, the best defense is one able to transform the victim into a contemptible Medusa, to make of the accuser the accused,” writes Jamie Hood, author of the new memoir Trauma Plot, in a recent Bookforum review of Virginie Despentes’s novel Dear Dickhead that begins with Pelicot’s trial.

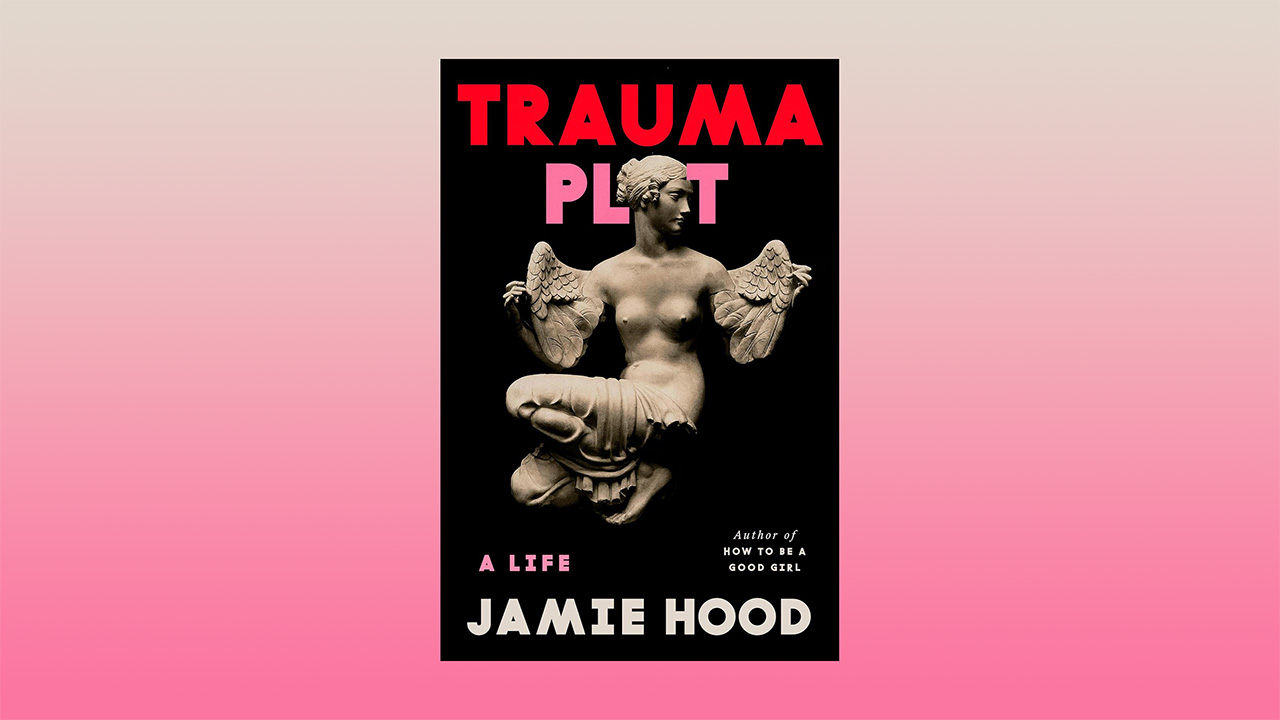

In Trauma Plot, Hood delineates her experience surviving three rapes through a prismatic formal lens. Each chapter of the memoir switches from a first, second, or third-person perspective, charting Hood’s time in grad school in Boston and her subsequent relocation to Brooklyn, while also weaving in threads from her childhood. But time, in Hood’s hands, is anything but linear. Hood destabilizes what might be deemed the tidy story of rape and gendered violence, the narrative that claims narrative is even a suitable form with which to contain trauma. “Everywhere I went, rape followed. Rape was the little phrase repeated through the score of my life.”

Repeatedly in Trauma Plot, Hood interrogates the enterprise of the book itself, reiterating its subjectivity, its elisions, and the danger of the illusion of order. At one point, Hood writes, “I’m here to tell a story; I must make meaning from mess.” Later, in a second-person chapter, she asks, “Do I thrust on your experience a traumatic significance that wasn’t there? Is it my job, or perhaps my crime, to assemble plot, to force on your behavior an ineluctable causality?”

Over Zoom, with Roku City sliding by on a TV and Olive, Hood’s beloved dog to whom the book is dedicated, sleeping soundly in the background, I spoke to Hood about the sprawling, awe-inspiring project of Trauma Plot, how the book came together over the course of a decade, the moral imperative of dignity, and how to tell when or even if one chapter in a life can ever be finished.

In your most recent Bookforum piece, you write, “The persistence of rape culture relies on the phenomenological production of rape as an unbelievable, unchangeable, and ultimately isolatable fray in the texture of ordinary life.” Your critique, which begins with Gisele Pelicot’s recent trial, dovetails with Trauma Plot’s essential project. In your book, you structure your own narrative of sexual violence in a kaleidoscopic form. I imagine writing about the same subject matter differs when you’re in critic versus memoir mode. Has it ever felt as if editors want you to stay on a certain beat?

My interfacing with editors is always at will. I am a working writer, but I'm also a bartender. I don't rely on the freelance economy in a way where I can't say no to pieces.

That's something that I talk about in the book, which is the self-identification as “rape girl.” That said, I don't feel like people have been approaching me to write specifically about these topics. My editor at Bookforum either asks me what I've been thinking about, what's been top of mind for me, or he lists a handful of books that he's hoping to get coverage for and I pick among them. And that's what happened here. It just felt impossible to talk about the rape narrative and French culture in this moment without attending to the Pelicot trial.

There’s a consistent thread in Trauma Plot, your narrative and how it relates to other rape accounts, but also how “narrative” doesn’t necessarily function at all when delineating such an explosive series of personal occurrences. The introduction troubles the notion of linearity, of forward progress, especially with regards to MeToo. Each chapter is its own world and time is malleable. Past and present frequently collide. Can you talk about how the structure for the book came together?

The introduction came last and maybe that's not surprising. There were sequences of the second chapter, “I", that I had written probably three or four years ago. And I only remember this because I was doing an interview earlier in the week with Heather and Leah of the Limousine Reading Series. They were like, “Yeah, you read at the very first Limousine from Trauma Plot.” Which is to say, I started that chapter much earlier in the timeline than I remembered.

I was reading a lot of Janet Malcolm and Helen Garner and Didion. These are three foundation-stone writers for me. I was thinking a lot about that kind of work, about how they write first-person reportage, how Helen Garner and Janet Malcolm report on trials. In a much earlier iteration of the book, I had explored the idea of sort of fictionalizing my own rape trial. Obviously I didn't end up doing that and I think it would have been gimmicky. But I was interested in how to talk through true crime as a way of seeing the world and thinking about the Boston Marathon bombing and thinking about those Waltham murders that I remembered very clearly from when I was in grad school in Boston.

The book didn't click for me until I did the first chapter, “She", which also was originally first-person. I had been telling it autofictionally, very Sheila Heti, but I felt too close and it just didn't feel particularly honest. Once I decided to rewrite the first chapter in the third person, once I started exploring dissociation literally, where I take up myself as a character named Jamie H, and there's a nice long trajectory of women who do this in hybrid text, that was when I saw what the book was going to look like in its entirety.

At that point, I was very deep in therapy. I got into therapy pretty much as soon as I could. I was uninsured for 10 years and then as soon as I got on insurance, I scheduled all my surgeries.

And when I was in therapy and writing through that experience, I thought, “This is how the book needs to end.”

In the first chapter you write, “She thought to resist cynicism, but femininity seemed to Jamie inextricable from a curtailment of experience.” There’s a constant negotiation of what it means to document experience in Trauma Plot, not just in general but violent gendered experience, and the limits of how useful it is to try and retroactively graft meaning onto slippery periods of personal history. Each chapter, as it shifts points-of-view, seems to be interrogating or reorienting this kernel idea over a really elastic timeline.

I write in the introduction about how I picked the book up and then I put it down and then I decided it wasn't worth it and I burned all this shit. And all of those things are true. I think that the reason it took me 10 years to write Trauma Plot was because rape ultimately seemed to me like a formal problem. Like, I could not figure out how to tell the fucking story. This was a much more complicated, labyrinthine book when I sent it out on proposal, and I think it's why I got so many notes. Originally the book was going to be in nine parts–three, three, and three. One section was going to be different poetic approaches. Another was going to be a first-person memoir, then the last was going to be criticism. I was working on it in that fashion for a year or two. And it still just wasn't working.

I think I realized after a certain point that I had constructed this incredibly baroque edifice to write about my rapes and what it was doing was enabling me to avoid writing about my rapes. I think I was running from the story and I accepted that I just had to fucking deal with it and look into it and truly face this period of time. That was when the form started to gather force and congeal. I play a lot with distance and proximity. As the book progresses, I get closer and closer and closer to something having to do with “myself,” whatever that is. Starting the book out from a place of deep distance, where I'm a character, that felt really important as the breakthrough chapter that enabled the rest of the book to happen. With the second chapter, it feels so raw in a way. The fourth chapter, “We”, is the one that feels the most vulnerable and the most close to myself and part of that's because it's in the present.

In Chapter 3, titled “You”, you comment on a spate of your own diary entries in the wake of another rape, almost like an archivist cataloging documents. There’s footnotes and textual intervention. It feels like this temporally distanced conversation between two separate people.

Yeah, absolutely. I hadn’t looked at those diaries since I wrote them, more or less. Most of them, the ones truly way back, it shocked me because of how much I had forgotten. And how much I got wrong. I thought that I remembered how things went down and I wrote about them in How To Be A Good Girl, or at least alluded to them. During the grad school period, I asked myself, “When did I start using the word ‘rape’? When did I tell people? When did these facts begin to manifest? When did they seem apparent to me?” I had a very different idea of those timelines than it actually ended up being.

Rape is often dramatized in media as an earth-shattering act of violence that stops time and bends reality to its whims. I feel like the popular conception is that it’s this immovable force around which ordinary life can’t churn. But you write about how that wasn’t at all your experience, that part of the horror was that life kept going.

Any narratives that I saw that had to deal with rape presented it as something that was unimaginably interruptible in a usual life. In Lifetime movies, it would be the oldest daughter from The Nanny or something and she would have a totally normal life and be a popular girl and her parents would both still be together and then the rape would happen. It was like an upending of her entire world, this puncture moment.

For me, I was in survival mode for so long. Pausing for even a second to think about what had gone on or to process, it was sort of like, “I don't have fucking time for that. I can't pay my bills. I'm living on people's couches.” The last time I was raped, I was living on a friend's couch and men robbed me. I didn't have time to sit around and wonder “Oh, did I just get gangraped? How am I going to survive this?” I was like, “Oh, I guess I better find a fucking job. I better do all these other things just to be able to make sure that my dog Olive eats.” Rape felt less interruptive and more like gradations on a spectrum of trauma and violence that I had already experienced. It didn't seem unusual to me in that regard because intimate sexual violence happened to me when I was a kid. All my relationships with men were always incredibly dehumanizing. So in some regard, it was difficult to use the word “rape” because every guy that I gave access to my body treated me like shit. It made me wonder, “Was that just how it was? I didn’t die.”

And often, the only mode of public belief in a rape victim’s story comes if that person is killed. As if their murder or suicide somehow finally grants truth to an otherwise unbelievable account.

You know, that's such a terrifying thing to me about this book coming out. How much am I going to be subjected to those sorts of interrogations?

It reminds me of another striking, really moving aspect of Trauma Plot, which is how you situate your rape and the mundanity of rape writ large, with other instances of violence. Gaza is mentioned frequently throughout the book, less as a point of personal comparison and more as a lodestar for the interconnected cruelty that’s so prevalent and, crucially, so virulently misrepresented in the world. Was that element something you found as you were writing?

This is going to be a slant way of approaching your question. My therapist Helen and I, for a long time, worked through this block where I refused to grant my pain or my suffering any dignity. Maybe dignity is not the right word, but significance. I was always hemming and hawing. “Who gives a shit about about this thing that happened to me because this is happening to this person or this is happening on a genocidal scale?” I was deep in the writing of the book in the immediate aftermath of Oct. 7, so this was top of mind and remains so.

In terms of imagining the interconnectivity, I do think about the fact that, as bodies, we are all fundamentally beholden to others. We like to imagine ourselves as discrete entities who move through a world that has something to do with us, but not specifically. And that's just not true. It can be terrifying, that porousness, and it often does result in trauma and violence and exploitation.

In grad school, I was studying a lot of Judith Butler. They wrote this book in 2005 called Giving an Account of Oneself, a slim tome about the production of subjectivity. People misunderstand Butler in so many ways, but part of the reason is because they don't understand Butler's engagement with performativity as an actual production through speech and speech act theory, that very structuralist history that's embedded there. And to me, I don't think you can really talk about Butler's notion of gender without talking about things like Excitable Speech, particularly the work in there about hate speech. Giving an Account of Oneself is very much about not only the production, how we account for ourselves in language and the philosophical histories behind us, but also the Subject as, again, fundamentally beholden to the Other. The Subject is produced in relation to an Other. The self is not a thing that exists in a vacuum. I think a lot about Butler's work in their book on Levinas and the ethical imperative that attends being fundamentally vulnerable to the Other. Levinas has the whole notion of the face: You turn your face to the Other and it's kind of like an ethical obligation that opens up in that moment where you encounter someone else.

People continually failed that ethical obligation with me. Someone actually looked into my face and said, “You are not worthy of being treated with dignity. You are not worthy of having your body protected or cared for. You were meek and that is a failure in this intersubjective encounter.” It's an ethical decision made on the part of someone who decides to commit violence.

So there's something bound up in the way that I talk about these things and also, I exist in the world. I cannot ignore the pain of others simply because I am in pain. Particularly around the Palestinian genocide. It feels to me like the moral knot of our time. I can't imagine not thinking through this and attending to this, and I don't say that to be self-important. I am not going to solve this geopolitical trouble with my little rape book. But it didn't feel to me that I could finish Trauma Plot without thinking about the way that genocide is operating in this discursive trajectory from, say, the War on Terror. Painting Palestinians as these violent rapists while the IOF itself is actually committing sex crimes on a systemic level against Palestinians, Zionist soldiers with Tinder profiles holding up the lingerie of women they've displaced or murdered.

It's shocking to me and I couldn't not have that be part of the thought process when writing about this issue in a personal way.

The book is incredibly personal, but I can't imagine talking about my rapes as if they happened to me in a vacuum. They happened in a political circumstance. Rape is political. Rape is endemic to patriarchy. It is inescapable in our world. It is the miasma. It's how I think we become produced as sexual bodies in some way. And it shouldn't be that way obviously and I dream of a revolution but it does feel like a very political issue to me and I can't just imagine myself as the sole nodule in this political realm. I have to imagine how it's operating in other places and to other people.

Our mutual friend Charlotte Shane has written about this a lot, the moral and ethical imperative that Gaza represents not just in the Middle East but the world. What it means to create a logic around cruelty, especially if you’re doing so through the prism of violence that happened to you. The logic of retribution that enacts a carte blanche of dehumanizing behavior. The difficulty but necessity of elucidating wrongdoing and speaking out.

Charlotte Shane forever! But yes, experiencing deep violence or trauma sort of becomes a blank check in a way. I feel like that's actually one of the reasons why so many people in literary criticism decided to repudiate trauma narratives. There was this idea that it creates morally uncomplicated characters. There is something to be said about the way that experiencing violence can award you some sort of built-in absolution. Maybe trauma makes you into a monster. For me, it kind of did for a long time, but my monstrosity I turned against myself and I think that's very apparent in the book.

One of the things that feels like a development for me is that I have relinquished the idea that I can control my life. But I have peace with that. We don't have control in this world. One of the things about the self-hatred that I had, the acting-out that I did, being really closed off to others, being really nasty to other people, very guarded and barbed and being willing to just cut people off — these were ways that I sought control. I thought, “The only way I can protect myself from further violence is making sure no one gets close enough to me to commit more violence against me.” An easy way to keep people out of your life is to be a huge cunt.

I did insulate myself from tenderness and from being with others because it was too frightening. Every time I was vulnerable, I was being exploited. And that's just not a way to live in the world. I lived that way for too fucking long. The quality of life has improved for me because I don't live that way anymore. And there are a lot of reasons for that. I have such deep friendships with a number of people and those friendships opened the world for me. Getting into therapy was huge. I was making a lot of these changes and improvements in myself prior to therapy, but I still hadn't really addressed the underlying issue, which was that I had deep sexual trauma that I had never faced, had never dealt with, even though I'd been writing about it or alluding to it or talking to people about it for 10 years. The other thing is that I fell in love and our relationship, as indicated by the book, ended last year, but it was the first time I had ever let someone in enough to love me and also the first time I had ever been loved by a man in a serious meaningful way. It reshaped my relationships with men and my relationship to sex.

Those things all resulted in me coming to a place where I actually do feel, “Yes, I'm not in control of my life. I could get raped again tomorrow. That could happen and I would have to deal with it and that would fucking suck.” But I feel so much more at ease. The things that I have control over: How do I treat myself? How do I behave with other people? How do I extend love and grace to people? I can't control whether or not an asteroid is going to hit the earth. I can't control if some guy's going to rape me. And living in misery and self-hatred is not going to change that.

How did you know where the book would end?

I'll answer in a multi-pronged way. For one thing, I am so bad with endings. But probably two or three months before I turned the manuscript in, I knew the line that would end the book. It’s the thing that Helen says to me over and over again during our sessions: I’m mindful of our time. Which always felt like such a gentle ending.

It’s been echoing in my head ever since I finished Trauma Plot.

I wanted it to end that way and I also wanted it to be unclear who said it, whether it's me, whether it's Helen, whether it's the sort of God voice. The ambiguity of the sentence itself structurally, grammatically, and also perspectively and how I position it, it feels like this opening. I knew that the book needed to end by opening outward.

I really didn't want it to feel closed or to feel like I was claiming some form of closure because I don't have closure. I didn't solve rape. I didn't solve my rape. I'm not over it. And yet writing the book was shockingly healing for me in ways that I was very resistant to. It felt exorcistic, it felt purgative and I'm not supposed to say those things as if this cured me. It didn't, but it kind of did. It's hard to get to the end of a project like this and be like, "Oh, wait. I got to the end of this, but the project of my life is ongoing." I had a conversation with Helen not that long ago. I was like, “You know, I could see a world in which I returned to the topic again, in an Annie Ernaux way.” What if 20 years down the line I think, “Well, I didn't quite do everything I wanted to do with Trauma Plot?” I leave that open as a possibility for myself. I have to follow where writing takes me. And that's true of life too. I have to follow where life takes me.

Maybe that's one thing that the sort of rivalry of most of my life has resulted in: a deep adaptability and knowing, in a way that is much less anxious than it used to be, that I have to take things as they come and take art as it comes. Because you can't anticipate things, you can't control things. We're not the gods of our world, you know?