Chinook salmon start their lives high upstream in the rivers of western North America. The young fish linger in the safety of freshwater until they are big enough to head out into the open ocean, where they can live for up to five years. At sea, the salmon shine blue-green and glint silver. When the fish head back upriver, however, they flush into warmer hues: olive browns, reds, and purples. The jaws of the males lengthen and hook. The salmon almost always return to the exact stream in which they were born, following the Earth's magnetic field like a compass. There, the salmon meet, mate, and prepare to die.

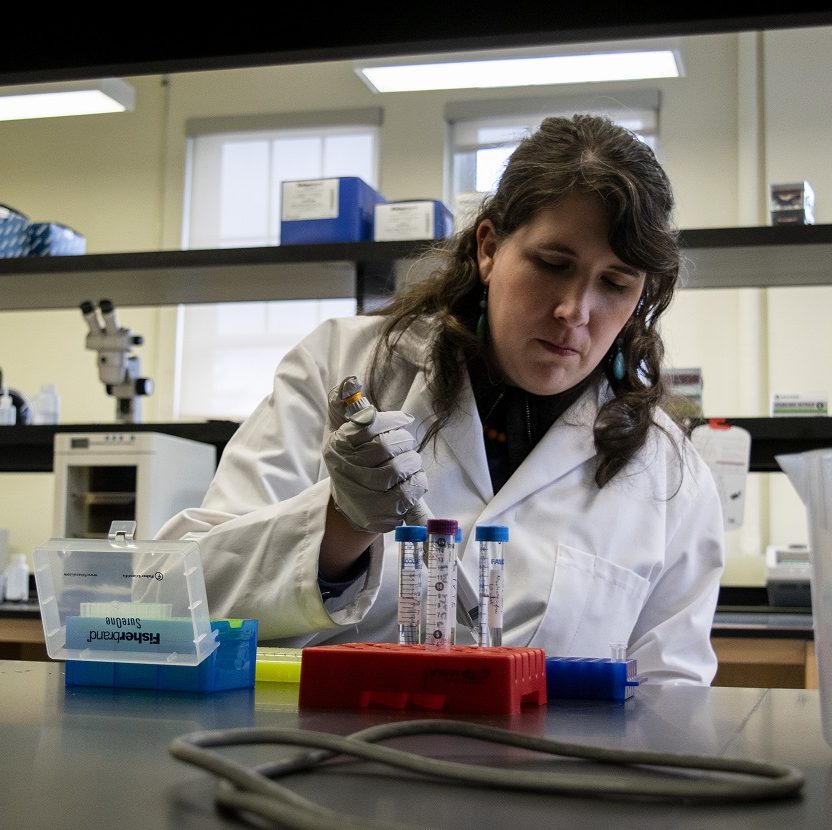

At this stage of the salmon's life, they become "gruesome zombie fish," said Sara Hugentobler, a fish biologist who worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the hatchery evaluation program in Red Bluff, Calif. "They're losing scales. They're losing tissue. You can see exposed bone." But this orgy of death leaves behind a bounty of carcasses—a buffet for bears and other scavengers. And whatever flesh, bone, and scales remain sink to the riverbed and become fertilizer for more life. "They're a really important ecological part of the environment," Hugentobler said.

Chinook salmon are also commercially important fish and a traditional food of Native American tribes in the region. In the 1940s, the construction of dams like the Shasta Dam blocked some Chinook salmon from accessing their historic breeding grounds. The loss of this ancestral breeding habitat is one of the main reasons why a group of Chinook salmon called the winter run is endangered. Several USFWS hatcheries breed and release young salmon each year to make up for population declines caused by the dams. And the hatchery evaluation program analyzes the hatcheries' methods and offers recommendations to most effectively support the salmon. There, a team of eight, including Hugentobler, worked to ensure that as many young salmon as possible would return one day to complete the cycle.

On Feb. 14, Hugentobler and two other probationary USFWS workers on her team were fired under the mass layoffs directed by Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. The majority of their team's funding did not come from the federal budget, but rather from long-term grants. Hugentobler has since been technically reinstated and placed on administrative leave after a series of successful legal challenges against DOGE. Her first day back is set to be March 31, pending no further chaos. I spoke to Hugentobler about the extraordinary life of salmon, the warning signs of her termination, and the threats the layoffs pose to endangered species.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Could you tell me about how you started studying Chinook salmon, and talk a little about your relationship with that fish?

I came of age during the Lisa Frank obsession. I was very obsessed with dolphins and all of that. So people had been saying to me since I was 12, oh you should be a marine biologist. When I was in high school, my mom took me to a talk with an author who wrote about ocean conservation, Carl Safina. There was a little mixer afterwards, and I got to go talk to him after that, when I was, I don't know, 17? I didn't know what I was doing, but that was the first time I'd ever thought about conservation. I'd never heard of overfishing before. I'd never heard of conservation in general. I guess I, at that point, had thought, oh, I'm just going to be in biology, and maybe I'll go train dolphins at Sea World or something. But then I think that really sparked something in me, and I was really interested in biology and conservation from that point forward.

I read Kaesee's story, and I know Kaesee personally—we did the same internship program with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Different locations, but we did it at the same time, so I'd met her previously. She talked about not being able to go out of state for school, which was the same with me. We were like sisters in different places, right? I was in Utah, which is very similar to Nevada in that it's not close to the ocean. But I couldn't afford to go to school out of state, so ended up doing biology at the University of Utah and then hoped at some point I would move closer to the ocean.

[After college] I worked at an aquarium in Utah for a little while as an educator, because that felt like the next best thing. I did presentations for elementary school kids about marine science and biology and things like that. Did that for a little while, and then I eventually did a master's in New York at Stony Brook University in marine conservation and policy.

I got into graduate school at Michigan State, which also seems like it's very far from the ocean, but my advisor had worked on Chinook salmon before. She still had ongoing projects in California that she was running from Michigan State, so she gave me the choice whether I wanted to work on a species in Michigan, or whether I wanted to help her with her projects in California on Chinook salmon. So my PhD was on the genetics of Chinook salmon. It's sort of a full-circle moment, because Carl Safina writes about salmon in some of his books that he had written at the time that I had known him.

And it's nice to work with a fish that is both marine and freshwater.

It represents its own unique challenges, right? Because it's a marine fish but also a terrestrial fish during different points in its life cycle. It's managed by two different agencies. So usually U.S. Fish and Wildlife has jurisdiction over endangered species, but because it spends some portion of its life in the ocean, actually NOAA manages them. And then we work for NOAA, in a sense, to help manage them. Or did work.

I knew since I had done that internship that I really wanted to work with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It was a really great place to work. I really enjoyed all the people that I worked with. They were all very nice and very passionate, and seemed like the place that was where my people were. The people that care about the same things that I do and really work hard to protect species. That position had come up on on USAJobs. I knew that I had a really good shot at it, since I've been working on salmon for so long. And it was in the same river of the same salmon that I'd been working on.

I would love to hear like what an average day looked like for you.

It was really variable. I will say I did work on [the] computer a lot. We work on a lot of reports and things like that, and also data analysis of how the hatchery populations are doing. I will say that I'd only worked there for three months, so it was still trying to get my feet under me. But I was helping with some of the government mandated reports they have to do. We have to do what's called a biological assessment. We have to outline how the hatchery fish are affecting native populations, and how all the actions that the hatchery takes may or may not affect the endangered populations. So that was a part of my job. Then we also do some amount of field work where we go out into the field.

Right before I was fired, they were doing some acoustic tagging of the winter run, the endangered species. That involved surgery where they implant the acoustic tracker so they can track the fish from the point that they're juvenile until they're adult and when they return. I wasn't doing the surgery myself, but I was doing some of the data collection for that. So that involves sitting across from a surgeon, and there's some amount of time that the fish can be operated on, and we have to watch very carefully the amount of time. So I was data recording and timekeeper for the surgeons as they're operating on the fish, to make sure there's minimal stress and damage to the fish.

They're held at the hatchery, and then at some point they are released to go into the ocean. So what might kick off that decision is if, for example, if there's a big rain event. If there's going to be a rain event, it might be better to let the hatchery fish go a little bit earlier, so that there's more water, so there's a better chance of them getting downriver. As opposed to maybe waiting, letting them grow a little bit longer, and they'll be bigger and they'll have a better chance of surviving, but maybe it's dry and they aren't able to make it all the way down river and get to the ocean. So it wasn't uncommon, at least in the three months of time that I was there, first to be called into a meeting, and my boss [would] say, "We're looking at this big rain event happening this weekend. Should we talk about letting the hatchery fish go? What are the pluses and minuses?" If it was pretty certain that it was a rain event, then there's some amount of preparation we have to do. We might be doing surgeries. Or we might be doing—they call it pre-liberation sampling. All hatchery fish have to be marked. They get their adipose fin clipped so that you can tell just by glance that they're a hatchery fish. We have to evaluate some amount of the hatchery fish to see if they've actually been clipped and if they actually have tags on them and things like that. That's part of our job.

It's easier to release the hatchery fish if there's a rainfall event because they'll have a better chance of surviving?

If there's a big rain event, the river is going to be more full of water, right? And if it's more full of water, it's easier for them to get all the way down. If it's the dry season—and this is within the context of, like, if they've been at the hatchery long enough. We wouldn't make this decision every rain event. They'd have to have been in the hatchery for some amount of time. But we might let them go a little bit earlier than we expected if there was a rain event a few weeks prior to when we would usually release them.

They're between six months and a year old usually, depending on whether it's a fall or late-fall fish.

As you were only work for a couple of seasons, would you have been doing different tasks in spring or in summer, or would your day-to-day be the same year-round?

So there's a big concern in our office, specifically, because one of our biggest seasons is the summer. We do something that's called the spawner survey. So in the summer—from what I understood, because I hadn't been through it yet—we have a few biologists on our team, but then we also have some technicians that are full-time, that we work with on our team. [We] basically go out every day in the summer and go up the river, looking for carcasses of salmon as they're starting to spawn.

They have a little tag—all of them do—so that we can recover them and do analysis on how many fish were recovered in the river. How well is the hatchery doing in terms of fish returning? And as I understand it, that was like an every-single-day event. Everybody on the team is involved in it, switching off so that people don't have to go seven days a week.

Some of them will return to the hatchery, but some of them spawn somewhere else, or downriver, or die before they can spawn, or things like that. It's a big survey. And it's in the Sacramento River, which is the biggest river in California. It's a pretty big undertaking.

Could you talk about your firing and how you experienced it?

[In January] executive orders started coming out—one of which was this executive order about DEI and not allowing DEI, right? So there was some time where there was some confusion about, like, OK, what does this mean at an agency level, and how do we have to respond to this?

There are employee resource groups, and I think other agencies have things like this as well. There's an employee resource group for for women, and there's employee research group for BIPOC people, and there's a pride employee resource group, and things like that. Do these things count as DEI, etc.? They had said, OK, well now you're only allowed to spend two hours a month on these resource groups. Which is like, OK, great. If we have one meeting, that's the entire month of work. Then after that, we got notice to please not post anymore in the team chat for the employee resource group, which is like the work chat. Which was sad, because it was this inclusive part of the work that wasn't necessarily part of my work. But [it] was something that made working there nice, and made it feel inclusive, that got taken away.

We got an email from [OPM] that said something like, it's your duty to report if people are participating in DEI initiatives, and if there's any effort to reclassify people who are working in DEI [to] keep them from getting fired. Things like that, which was just scary. Like it's your duty to report on your coworkers if they're working on DEI things? That was this scary backdrop to what's happening.

I was only required to come in office once a week. So I was at home that Friday and was just watching Teams, because Teams will tell you when people are in a meeting or not. And I saw that morning that my supervisor was in a meeting, like, two hours that morning. Then after they got out of the meeting, just sent me a one-sentence message that was like: I'm sorry.

We all met in our conference room. It was all the people that were probationary, and then their supervisors. The atmosphere was so bleak. I've never seen so many grown men cry at once. Everyone was just in tears.

The two techs that got fired, sitting with them, this was their first job right out of they got out of college. Just also knowing that it was just really hard for them. They were two weeks away from not being probationary anymore. Both of them. They'd been hired at the same time. It just felt so terrible and so unfair. They were so close to not being cut. And then I had just moved there, like moved my entire life, and then only been there a few months. It's just terrible.

Could you talk a little more about what you fear your termination and your colleague's termination will mean for your department, and the work you were doing for the hatchery?

The day that I left, one of the other fish biologists had said to me, "I finally felt like we were going to get things done." They just hired me. We had these technicians that we work with that were full-time and were really great and were doing really great work. Everybody on the team got along really well and worked together really well. That's almost half our team gone.

I had learned to code. No one in my office really knew how to code. So what that meant was that any data analysis could be done faster. I was working with one of my coworkers to fast-track some of the data management stuff that takes a long time. Previously, they've been working in an Excel spreadsheet and just doing it all manually, which is important but takes a long time. I was really excited to start working with them on ways to streamline their process with coding, so some of that stuff didn't take so much of their time. So they could really focus on the things that were important to work on, instead of trying to mess around with huge data spreadsheets to get them ready for analysis and things like that.

Another reason that they had hired me was because I had this experience in genetics. I was really starting to see my supervisor lean on my experience. If he had a question about what something meant genetically, he would would ask me. I was just starting to feel like I saw ways that I could really contribute and improve the office before I left.

I worry too, for them, that the office will be cut down even more. We're hearing that agencies have been asked to submit plans to reduce right their workforce by 20 percent to 40 percent. So going through what they call a reduction in force, where they fire some of the the government employees. So I feel like many of my colleagues that are still there also feel like their positions aren't safe and that the office will continue to be cut down.

Would you want to share any thoughts on the future of the department, or USFWS more broadly, under these threats?

If these threats come to fruition, which remains to be seen, it's hard to imagine that there will be much left. If 40 percent of the office gets cut, that's a huge amount of people. It's hard to imagine that all the important work that gets done—not just by my office, but by the agency—will be able to continue in any sort of meaningful way. I feel like people have been saying—and I have experienced—that offices were already understaffed. It's not going to help with that.

For endangered species, that's a huge, huge, huge part of what the service does. There won't be people to essentially speak for this species, or to stand up for them, or to mitigate some of the consequences for endangered species. It's hard to even imagine what might happen. I've heard they've stopped listing decisions as well. So whether a species is listed as endangered or not, that's been stopped. People like us who do surveys to understand what's out there, those are not going to be able to be completed with the skeleton staff, right? We'll just lose all these surveys we've been doing for how many years—will just be stopped. It's kind of scary.

Our species and our lands and all these things that we care about are in the balance right now.

If you are a fired federal worker or contractor interested in speaking with me for this series, please contact me on signal at simbler.88 or simbler@defector.com. I would love to hear from you.