There's a new sports sponcon documentary out, and this time it's about the little-known story of a mini-dynasty from Dallas that reigned during the end of the last century. That's right: It's the '90s Dallas Cowboys' turn to be exhumed for easy, bloated content. In my best Stefon voice, this documentary has everything: old men crying about sports, guys to remember, cocaine, strippers, former presidents as talking heads, even scissors in a guy's neck!

Netflix's new eight-part documentary America's Team: The Gambler and His Cowboys covers the entirety of the self-important franchise's last gasp of true relevance. In the wake of The Last Dance, many documentaries have tried pretty transparently to borrow from its style: its over-the-top sense of drama, its trading of actual journalism for the glamor and pathos of player testimonials, the carrying on about how "you couldn't do this in today's game," and of course the kitschy, time-stamping needle drops. But America's Team might be the most blatant attempt by a documentary to follow The Last Dance's roadmap, right down to the framing of it all around one central figure, here plugging Jerry Jones into the Michael Jordan role.

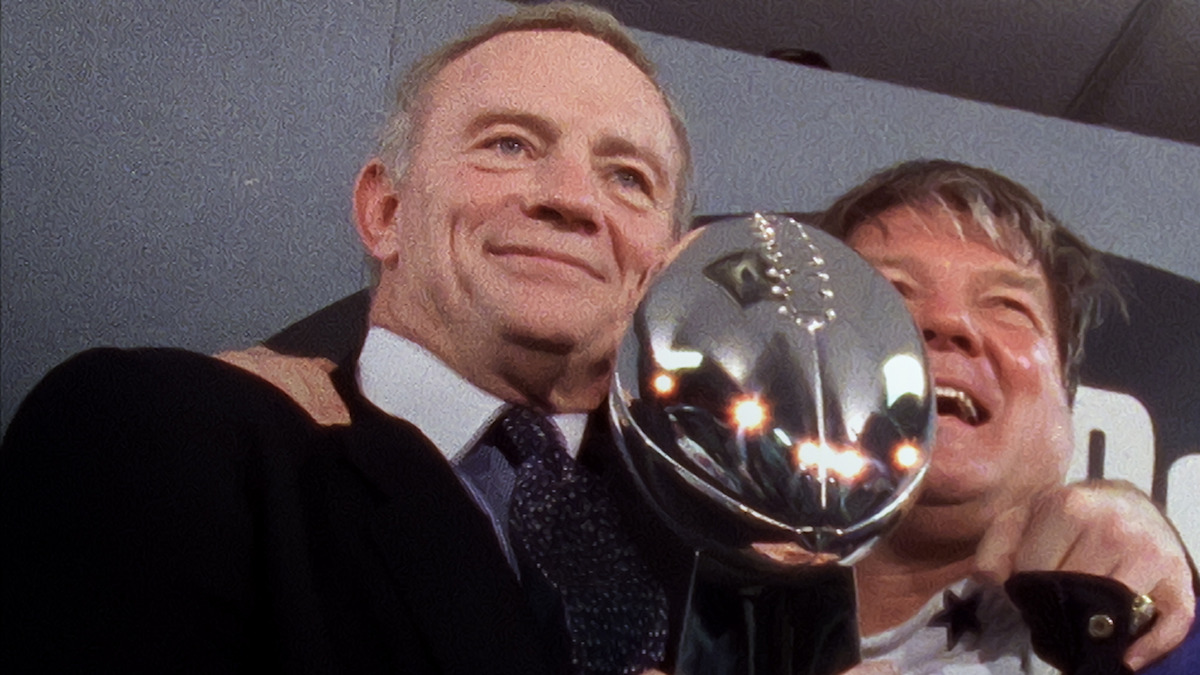

As such, America's Team is a documentary about Jones first and foremost. It begins with him retelling his villain origin story about when his oil mine hit black gold and earned him $100 million, and how his plan from that very day was to buy the Dallas Cowboys. Everyone else involved in the success of those teams in the '90s—you know, the actual players and coaches—plays a secondary role, recounting the good times of being a Cowboy but mostly just validating Jerry's many gambles to get them there, things like his decision to fire Tom Landry and Tex Schramm unceremoniously in his first week, the Herschel Walker trade, and his battle with the NFL's commissioner and other owners over the right to do separate brand deals with his team. Even at moments when you're getting into the well-trodden but undeniably compelling stuff with the team, and you're loving the old game footage and Michael Irvin is stealing the show the way he tends to, the documentary will just go off on some Jerry-related tangent that you don't actually care about. This doc, even more than The Last Dance, is terrible at sticking to any kind of coherent timeline or narrative through line. Which is not surprising, seeing as poor editing is a hallmark of the Netflix documentary industrial complex.

Was anybody really asking for this? It's hard to imagine a viewer who would be interested in this topic but also wouldn't already know the main beats of the story. There's nothing new to learn here—not about the Cowboys, not about Jerry, not about Jimmy Johnson and his eventual blood feud with Jerry, not about Troy Aikman or Irvin or Deion Sanders. It's like the world's oldest museum at this point; everyone has already been through it. That isn't to say there aren't fun moments. Those 49ers and Cowboys games were almost always more interesting than the actual Super Bowls. Seeing the on-field assaults Irvin and Aikman would have to endure makes you wince while also making you a little nostalgic. Personally, I could watch Johnson talk about his coaching style all day. Like all the docs in this genre, the old footage is the best part, and there really is a lot of great old footage.

Still, the Cowboys series suffers for the same reason The Last Dance did, and for the reason all these new sports sponcon docs do. It's this love affair with myth-making over facts and history. There's value to listening to the athletes, coaches, and front-office people who were directly involved, but that doesn't mean their voices are the only ones that matter. Usually in these docs journalists are afterthoughts, if they're included at all, and the types of journalists included are often telling. The most prominent journalistic voice in this one is Skip Bayless, who earned his sordid reputation writing tawdry stories about the Cowboys to sell books. His presence, like the man himself, is embarrassing, but it's what we've come to expect from this genre: people who are journalists in name only, and insiders who gained that status by carrying water for the powerful. Historical accuracy, new insight, proper context, the search for truth—none of that stuff is important to these documentaries, which exist solely to entertain in a way that flatters the most important subjects and inculcates positive feelings in the viewers. Who needs all that pesky vetting if it might get in the way of the story being sold?

Speaking of telling stories: One story America's Team repeats is the time Jones took separate brand deals for the Cowboys, back when the league still believed in shared revenues and split profits. The biggest of those deals was one with Nike, which may or may not have helped them sign Deion Sanders to one of the richest contracts in the league at the time. Jerry was seen as a troublemaker by the rest of the league, someone who was ruining the sanctity of the sport, so much so that the league sued him over the deals. Of course, since this is Jerry's documentary, this makes him a "maverick." Current NFL commissioner Roger Goodell shows up to argue that Jerry was just the first to see a future that the rest of the owners and then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue could not. It's always interesting how our most fervent capitalists never actively create a new future, they simply see the way the world must go, and through that clairvoyance they are absolutely powerless to the march of progress. But hey, this is Jerry's show, so we can trust that he always knows what's best.

Indeed, the future Jones foresaw is in fact the one the NFL lives in today. Instead of a club for bored rich people, the league is its own fiefdom where mini kingdoms abound. Part of what's fascinating about sports is how they explain the world in miniature. Here we have rich owners using power, money, and influence to alter the world around them until it better suits their egos and bank accounts, regardless of what it does to everyone else. We have a commissioner (kind of like a president) who ostensibly works for everyone, but in reality works exclusively for the interests of the ownership class. Workers and consumers exist as bases to exploit in furtherance of those interests. If that sounds like, well, every other facet of life, then you're seeing the point.

Maybe there is something new to learn from this docuseries after all. The doc explains that the origin of Jones's obsession with owning a football team goes back to his college days as a member of the 1964 national champion Arkansas Razorbacks football team, alongside teammate and roommate Jimmy Johnson and a young assistant coach Barry Switzer. Like many other mediocre men, Jones's primary motivation was to recreate a moment in his youth, and he quickly discovered that none of it, not even winning three Super Bowls, could compare to the bliss of being 20 years old, in the prime of youth, having fun in college, and being part of a winning team. The time has passed, and the memories are a narcotic.

If there's one thing that most bothers me about this trend of poorly made, uncritical, advertorial pseudo-documentaries, it's how they eschew an urgent story about how we keep ending up where we always end up, in favor of yet more pablum that plays on, but never challenges, the so-called halcyon days of yore. It's worse than slop, because slop would make you gag. This always goes down easy: a tranquilizer of remembering the good times. Jerry Jones understands the feeling.