For a few years, Maggie Nelson was everywhere. The celebrated autotheorist is the voice of, if not a generation, a meaningful corner of one; her 2015 memoir The Argonauts is one of the rare unifying must-reads of the millennial intelligentsia. Nelson is omnipresent within her own work, too: She theorizes on sex in the Chelsea Hotel and the birth of her son, philosophizes the shades of her own grief, pairs her experience alongside quotes from Lacan and Sontag. While she didn’t invent the critically informed memoir, she’s created a version that now feels ubiquitous—immediate, intimate, pulling from an expansive database of external sources, like if a Romantic poet had internet access.

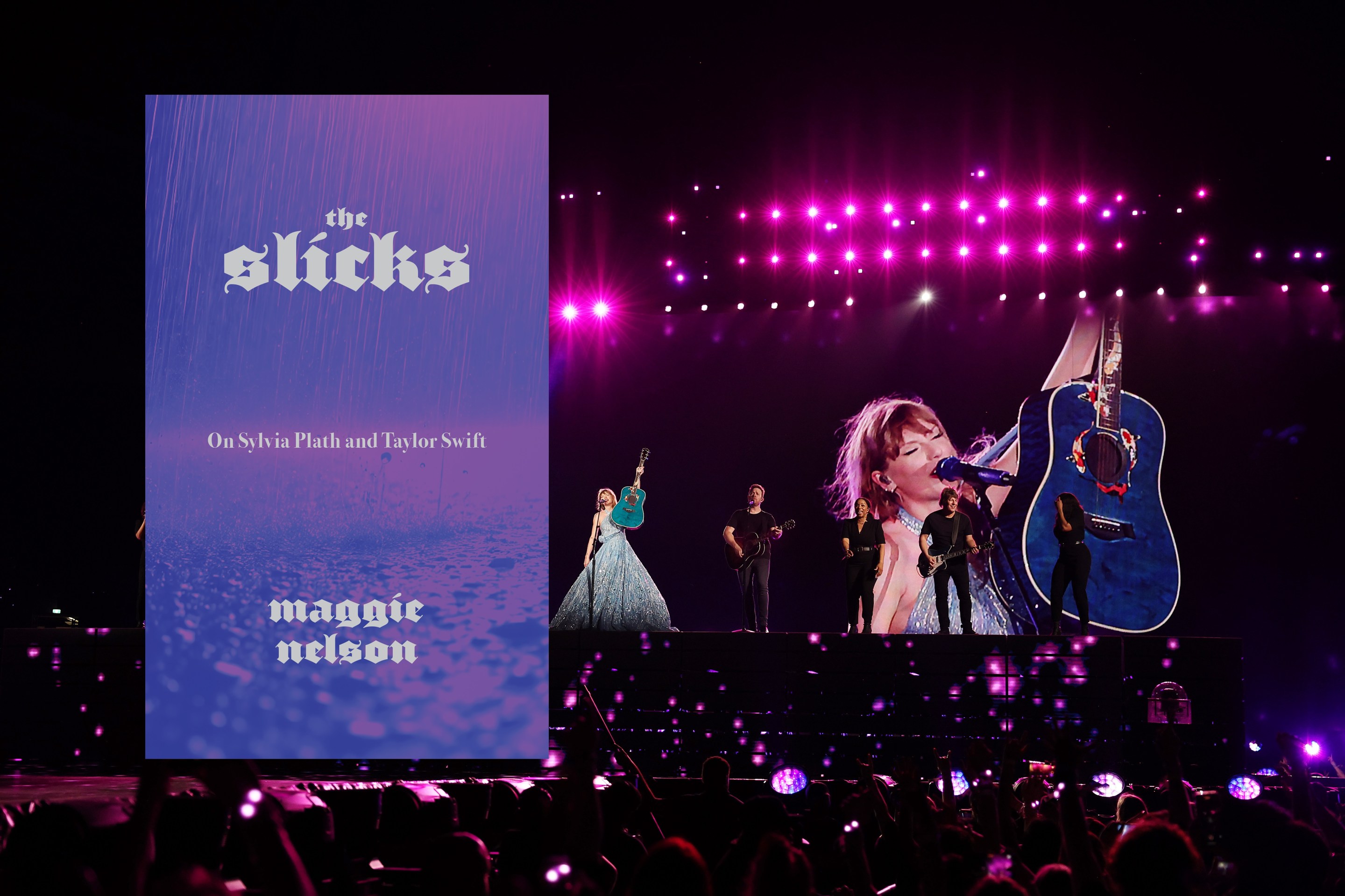

That her latest book is called The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift was cause for some trepidation, but I held out hope. After all, the book claims to take on Swift and Plath as “twinned targets of patriarchy’s ancient urge to disparage…creative work by women rooted in autobiography and abundance”—an apt description of Nelson, as well. As eyeroll-inducing as anything written about Taylor Swift as a victim of patriarchy may be, Nelson’s own career as a thoughtful and capable memoirist promised that The Slicks might hold some great wisdom on the nature of autobiography and womanhood. If anyone could pull it off, surely it would be Maggie Nelson.

Let me spare you the suspense by saying it now: She doesn’t. The book is ill-conceived and poorly wrought, a cynical scripture from the Church of Taylor Swift that relies on circular, shallow argumentation leading the reader nowhere. The central premise, that Swift and Plath are both victims of the patriarchal distaste for prolific woman artists, comes off as tired and outdated; parts of the book read like they belong back in 2015, on the shelf beside a Ruth Bader Ginsburg mug. There’s a notable absence of many of Nelson’s usual strengths—a penchant for universalizing the personal, a deft application of critical theory—and the strengths that are evident, namely her vast wealth of knowledge about poetry and literature, are drowned out by a poorly considered “feminist” argument that reads more like a chip on Nelson’s shoulder than a legitimate political issue.

Nelson had to know that her argument was a big swing—the promotional materials describe Swift and Plath as an “unexpected pairing”—so it’s surprising that the book is so brief (just 51 pages!) and unstructured. The reader is rushed through a series of progressively harder-to-swallow claims and meandering paths of contradictory evidence about Swift and Plath’s careers, leading to an elegant but incoherent conclusion that we should celebrate Swift’s “jouissance” and “let it rain.” Throughout the text, Nelson oscillates between drawing the two together (both function as a “metonym for a woman who makes art about a broken heart”) and highlighting their extreme differences: Plath died in middle-class, purgatorial anonymity while Swift is a billionaire superstar; Plath’s art reflected the depth and grotesqueness of her inner darkness, while Swift primarily writes in platitudes about a series of heterosexual misadventures; Plath is a poet and author, while Swift is a pop star who claims literary affiliations but, as Nelson notes, “is not trying to be a great poet.” This is the most bewildering statement of all, given that the book’s premise is built on Swift’s persistent branding as a writer first, if one who has stumbled into pop stardom. By the end of the book, Nelson has spent more time elaborating on and then brushing away these essential discrepancies than she has convincing the reader that the two women have anything in common.

Still, Nelson insists that Plath and Swift, despite their varying circumstances, are similarly victimized by the patriarchal distaste for the “female urge toward wanting hard, working hard, and pouring forth.” While Plath did inarguably suffer from the sexist limitations of her time, Nelson focuses primarily on Swift as a case study. And given that Swift has achieved an almost world-historical level of success, it’s a hard sell. She details the critical reception of Swift’s two hour, 31-song 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department, which she claims followed a patriarchal “script” that aims to “moderate or chasten” Swift’s artistic “flow.” She points to the New York Times review which argues that the album was strong but could have benefitted from editing—hardly a sharp condemnation—and follows with a quote from the same publication that asks, “Will Swift ever voluntarily step away from the spotlight?” A damning question if it were the framework of an op-ed or a quote of a critic, as Nelson implies; upon research, the reader will find that the question is one of several listener-submitted talking points in an episode of the Times’ pop music podcast. As for the claim that critics don’t like autobiographical work, Nelson relies on a quote from an Anne Carson essay on the gendered nature of self-censorship and a headline from an op-ed by the universally reviled conservative commentator Ross Douthat. Nelson then goes on to clarify that Swift’s fans, of course, “adore the abundance,” are “passionately drawn toward deeply personal work”—as if only critics are subject to patriarchal norms, and fans are magically exempt from outside social forces. The landscape of repression upon which Nelson’s entire argument relies is only somewhat persuasive on a first read and nearly vanishes upon review.

And what about Plath? The strongest parts of the book focus on Plath’s relationship to poetry and to other female poets, such as Emily Dickinson, who appears throughout the book as a kind of specter of what could have been had Nelson not invested herself in adjudicating Swift’s poetic accolades. There are moments of more typical Nelsonian insight in the sections on Plath—a lovely musing on how poetry is inversely correlated with wealth, on Plath’s fame being birthed out of the tragedy of her death—but none of these reflections serve the book’s central argument about patriarchal repression. If Swift is victimized by a handful of critics, a victimization which merits numerous pages of detailing, Plath’s repression is largely left to vague allusions to negative public reception when she was alive. Today, as Nelson notes, Plath has achieved public acclaim. In fact, a quote Nelson pulls from the Times criticizing Swift points to Plath as an example of a “great poet” who “[knew] how to condense.”

The irony of Nelson’s neglect of Plath is that she did indeed suffer at the hands of patriarchy, her brilliance rejected in her time as the musings of a bored housewife. The tragedy of the woman poet who killed herself in the kitchen, using the tools that kept her small to end her life, has not been reduced to a “meme,” as Nelson claims—it’s a cautionary tale about stifled genius. She worked and worked and never broke into the titular slicks, until it was too late for her to reap the rewards of her labor. There’s something to be said for putting Swift and Plath in conversation as representations of what happens to shrewd, ambitious women in their respective times. Nelson forgoes this opportunity for historical reflection to instead conflate the very real limitations that Plath faced as a woman artist of her time, with Swift’s self-proclaimed victimhood in a world that has by and large rewarded her for mediocre, commercialized artistry.

Swift’s “profusion” could be easily repainted as a relentless pursuit of commercial domination. Nelson cites her habit of releasing bonus track albums hours after initial releases; her Eras tour, which has racked in more than $2 billion; even her highly publicized remaster project, framed as a feminist move to reclaim power over her art, as proof of her work and dedication. They also result in the accumulation of an enormous amount of capital. Nelson celebrates Swift’s strategic “flooding the zone” by releasing a 31-track album, taking over the Billboard chart in the process, but it’s strange to attribute her motivations to artistic outpouring when they could be more easily explained by Swift’s business acumen. There are brilliant, prolific woman musicians who write deeply personal work who could only dream of achieving the kind of wealth and fame that Swift has managed to accrue in her relatively short life: Bjork, Courtney Love, Esperanza Spalding, Joni Mitchell—and all of these women’s work, despite their personal nature, despite their profuseness, have been critically acclaimed. The “round after round of resentment” Swift’s music provokes is surely colored in some way by the fact that people don’t like it when women become successful, as Nelson argues, but it’s hardly held her back, and there are plenty of reasons to resent Swift’s “outpouring” when what it amounts to feels like a vast commercial empire.

If and where there’s truth to Nelson’s claims, it’s completely muddled and undermined by inane argumentation in favor of the defense of a celebrity who is hardly under attack. Which raises the question: Why did Nelson write this brief, unwieldy book at all? The book doesn’t reveal much about the world, and we only get the vaguest sense that it reveals something about Nelson—a prolific woman artist who works primarily in autobiography, whose own career is left strangely unacknowledged. She writes extensively in defense of Swift, and to a lesser degree Plath, as women writing in the personal, but never does she note that she herself has built a career on “pouring forth” stories of her own pain and desire. The shadow of Nelson’s MacArthur Genius Grant, awarded for her work in memoir, hangs heavy over Nelson’s claims about the societal denigration of autobiographical art by women. There are a number of strange, almost meta moments in the text, where Nelson quotes Eileen Myles and Nietzsche to prove that art is inherently autobiographical, “the confession of its originator.” So, what is Nelson confessing with this book? She’s a Swiftie, no doubt, and a fan of Plath. She is upset that someone, somewhere, doesn’t like autobiographical writing. She is anxious about her own reception as a prolific woman author, but doesn’t feel justified in saying it outright?

As I read, I found myself increasingly frustrated. I had just read The Argonauts for the first time this year, and was amazed by Nelson’s capacity for reflection, her skill for needling through the sticky contradictions of womanhood and queerness. She’s a smart woman, and an excellent critical thinker. This book—which cries “misogyny” at the mere hint of suspicion toward her primary subject—feels less like an exploration of contemporary feminism than an exercise in contemporary fandom. That she claims thinking Swift’s album is too long is a symptom of the same “feral misogyny [as] the MAGA movement” and the “overturning of Roe v. Wade"; that she brushes aside critiques of Swift’s wealth; that she compares Swift’s artistry, and suffering, to that of Plath at all, demonstrates a kind of jaw-dropping lack of perspective that betrays the reader’s trust.

Whatever Nelson’s motivations may be, it’s hard not to read the book as a cynical attempt at maintaining relevance by tacking Swift’s name onto what would otherwise be a perfectly serviceable essay on Sylvia Plath. Her “feminist” argument is so poorly supported that one wonders if Nelson herself believes it. Her claims about Swift’s artistry in relation to Plath are contradictory to the point of saying nothing. Mostly, it reads like an amateurish imitation of Maggie Nelson, and we have enough of those already.