"People were writing poems," Patricia Lockwood tells us. Also: "People brought you cabbages." In her hands, events don't unfold in the usual way, with a beginning, middle, and end. Instead, we seem to come upon people and things doing what they always do, their actions and goings-on both a matter of course and an incorrigible fact of their existence. The sensation of duration and repetition accumulates and compounds, so that the feeling is that this, whatever it is, has been going on forever.

In a similar way, you could say people were reading Patricia Lockwood. She arrived on the literary scene, some 15 years or so ago, apparently fully formed, blurring at the edges slightly and yet for that all the more identifiable as herself. Her poetry, her uncanny ability to post viral tweets—back when that meant something, though no one had any idea what—her immediately recognizable prose style, all that having the feeling not so much of promise but fulfillment, an IOU from the culture to itself, finally being paid.

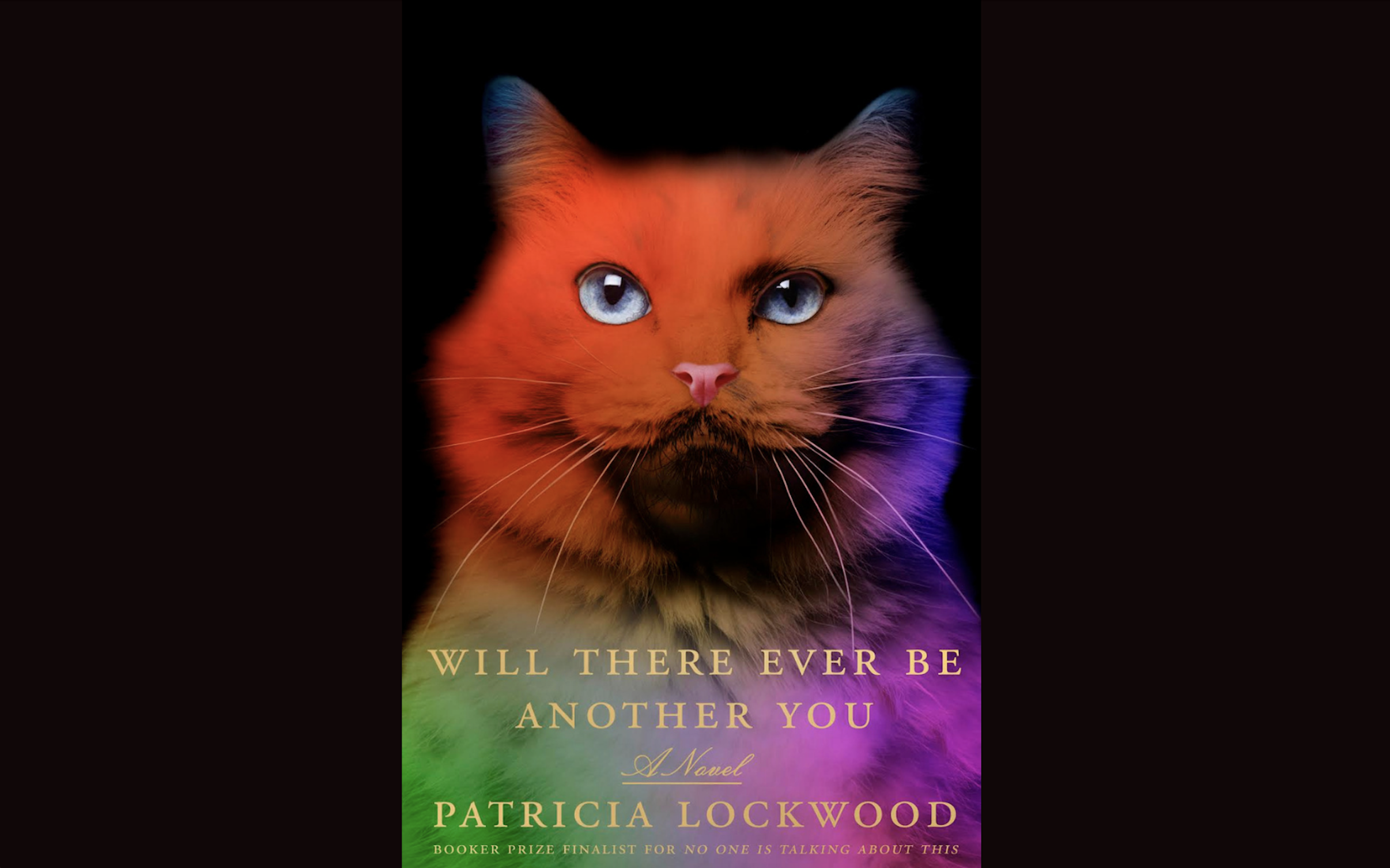

Lockwood's facility in pointing out that uncanny sense of things happening both now and always—exploring it, and yet allowing it to remain untouched, unspoiled, unconquered by explanation—has been among her greatest gifts as a writer of the internet and an internet-addled age. It has come to her aid again in Will There Ever Be Another You, her autobiographical novel of long COVID, that curiously social and socialized malady, the persistence of which is matched only by the doubt that it even exists.

The novel opens with a fictionalized Lockwood in Scotland on a family holiday. We follow Patricia through her life as an in-demand writer, trying to maintain her busy schedule as various events befall her in addition to her own illness: Deaths and near-deaths in her family loom large, but so too do things like reading tours and meeting the pope. From the outset, we're in the borderland between the ordinary world and a fantastical one. "As soon as she touched down in Scotland," goes the opening line, "she believed in fairies." But lest this seem like too welcoming an introduction, she follows it immediately with: "No, as soon as the rock and velvet of Inverness rushed up to her where she was falling, a long way through the hagstone hole of a cloud, and she plunged down into the center of the cloud and stayed there."

In Lockwood's world, there is little to separate the real out from the illusory, except one's own sense of self, one's own intelligence, which might be as complicated and intractable as the external world, but is one's own. In this opening passage, the world tries to assert itself with an easy association—of course you believe in fairies in Scotland. "No," the mind counters, insisting on the primacy of its own operation. No, I remember it differently.

Lockwood's voice, her peculiar sense of humor, her tendency toward the self-consciously idiosyncratic, has been the subject of a great deal of admiration and perhaps an equal amount of skepticism. In a mixed review of Will There Ever Be Another You for The Guardian, the critic Beejay Silcox wrote that the novel "feels auteurish, the literary equivalent of a Wes Anderson film: over-styled and perilously close to self-parody. A delirious in-joke." But Lockwood's insistence on her voice and her cast of mind is the clearest marker of her humanism, and is the saving grace of an otherwise tenuous relationship to ordinary novelistic standards.

It's a sensibility framed by dichotomies and dualisms, the boundaries between which are at once wholly given and constantly undermined. Her literary essays are forever straying between derision and admiration for the author, for their works, for the whole exercise. Her memoir, Priestdaddy, is from the title on down a play of opposites that may also be synonyms. Her previous novel, No One Is Talking About This, is split down the middle between "the portal," itself an infinitely self-dividing quasi-landscape of obscure, possibly meaningless references and self-references (in other words, the internet) and the imposingly real world of illness and family trauma.

Will There Ever Be Another You is at once more cohesive and more divided. It's short on plot, almost nonexistent in dialogue or the usual encounters between characters, and at times maddeningly chaotic in its thematic development; the fictionalized Patricia seems intent on nothing so much as her own sense of self, and that is precisely what is falling apart. There is one gigantic, terrifying, profoundly humane question at the novel's heart that carries us through all of its formal and conceptual demands: What if someone who doggedly, at times heroically insists on the importance of her own mind begins to lose it? "It"—the illness—"stole people from themselves. You might look the same to others, but you had been replaced."

The initial evidence of this, which resonates with much of Lockwood's past work, is that she begins to blur boundaries, especially those between subject and object, the events experienced and the person experiencing them. When illness strikes in Scotland and refuses to leave, lists begin to proliferate, as though the mere objects of her quicksilver attention were a replacement for thought, insight, action.

People lost their fingerprints, how was that possible? People were up at three a.m., contemplating the purchase of apple-flavored horse deworming paste, which had gone up thirty bucks a tube. People—or maybe just her—were becoming confused after they got out of the shower and applying large tracts of deodorant to the skin of their face. People had Alice in Wonderland syndrome, and something called Drunk Baby Head, and glittering damage to their vegas nerve. People were writing poems about it—hahaha, she said whenever she saw one, though she used to write poems about everything that happened to her. People had Brian fog—oh no—and people did not recognize themselves. People stood in front of the mirror in the bathroom, flicking the lights on and off to see if their pupils were the same size.

This is, at first glance, a list of Lockwood's own internet searches, but as the lists go on, both in themselves and over the course of the novel, the provenance and location of the phenomena she lists become increasingly unclear. In this way, the illness that bedevils her is not unlike the internet, in the ordinary sense of untrustworthy sourcing and in the more troubling way that the scroll becomes the place you spend all of your time, even though it doesn't exist. The difference is that while the internet scrolls on indefinitely, even as it gets shittier all the time, a person really decays, really loses hope, really can die.

But again like the internet, there is little in the process that is linear. The narrative, such as it is, of Will There Ever Be Another You proceeds by fits and starts, with bursts of luminescence followed by fizzling and sputtering. As the surface of her mind gets scratched away, Lockwood's literary intelligence, never in doubt yet ironically easy to overlook, emerges with refreshing, if slightly unnerving clarity. References and readings abound: Shakespeare, Walter Benjamin, Proust, the Bible. Better when she's thinking through—if that's the right phrase—what literature has made of her life:

Warm skin was the surface we polished and polished toward. It was not like poetry at all, or else it was—it is like your words are washing me, a student once said after a reading. It was like it ended a dozen times before it did, said another.

But the disintegration of the mind accelerates:

I was subject to a different law here, and I could make it: amulets, worry beads, coins free of any country. I could marry people more properly than my father, tie a knot that would last a thousand years. Then I was rising in the air. Then I was upside down, mining opals in Australia.

Running through all of this is Lockwood's religious sensibility, which rests comfortably within the sacramental and iconographic tradition of European Catholicism even as it grates against the ubiquitous contemporary assumption that Christianity is a dour, abstract thing. When her husband suffers a medical catastrophe—a kind of intestinal blockage that requires major surgery and leaves him with a massive gash down his side—the language she finds is invariably sacral: "According to the scale he weighed 140 pounds; his Christ now belonged to the Middle Ages, rather than the Renaissance." The Wound, as they call it, resonates with nothing so much as the side wound of Jesus, right down to the gender trouble it helps to elicit.

Illness, physical disaster, bodily collapse have always been linked to the mystical. In the first days after her husband's surgery, he begins to babble into his Notes app: "There is the Spirit Layer, and there is the God Layer. The God Layer is occupied by a single entity called God, whose materiality stretches out infinitely and fills its whole layer." And so on. It's charming and a bit silly, in a way Lockwood often spins her material to be. But in these unprecedented depths, something else emerges: fear. "It was so funny, the sound of it—why did new religions always sound like that?—until you realized it was the clarity of a man beginning to starve. It had now been seven days since he had eaten, and his thoughts had climbed up into thin white air. 'Please,' he said to anyone who came into the room, 'please.'"

For a certain subset of the devotionally online, the relationship between physical collapse and a brush with the transcendent is a given, almost old news. For Lockwood, who is a kind of fellow-traveler-cum-anthropologist of this mentality, that's exactly where it becomes interesting: not in novelty, but on the precipice of cliché. She is the great stylist of millennial exhaustion, of that afterglow of paranoia, which, having confirmed that they are, in fact, after you, has settled into love—of whatever—of Big Brother. It makes the success of the book, and of its author, all the more astounding, having found a voice at precisely the point where someone else's—anyone else's, really—gives out. But what makes Lockwood more than a mere stylist, and what really accounts for the power of her work, is that something comes after exhaustion.

By the end of the book, in part buoyed by Lockwood's own care of her husband, the illness seems to have receded, however much devastation it left in its wake. But in the wreckage, nearly everyone more or less alive, she begins to build again: The closing pages have her constructing an island in her imagination, an island like Crusoe's, a literary place from which reality might be reproduced (if only as a reproduction), as well as a person to inhabit it, a cryptid she names MANGRO. "So what is MANGRO's deal exactly," her husband asks. "But in the process of assembly you couldn't say too much. I groped my way back inside the whirlwind of paper, the description coming in short pants. He's like a thought—or a light on the mind—he reveals. Not a piece of scenery but the person behind it. Looks like a tangle, but that's our un-understanding. All connections necessary. Not something wrong with the brain. The brain itself. I opened up the notebook (which I had brought like my family) to show."

This is hardly a triumph—little more than fragments shored against ruin. And beyond that, it's hard to know what exactly to make of them. Are we putting ourselves back together, or continuing to fall apart, now with an imaginary friend? There might well be some wisdom here, but is that a filthy little pun I see? These questions have always attended the reading of Patricia Lockwood, but now the stakes seem higher. You can't log off of life, a fact all the more terrible the more it feels like we're always online. But what keeps us going along with Lockwood is how patiently she sits, and allows us to sit, in the affective swirl, noticing things as they pass by, sometimes slowly enough to care. Ironic as ever, yet transforming irony into the medium of sincere exploration, Lockwood's is a project of interior envelope-pushing, applying pressure at precisely the points where it seems we've already caved.

It's encouraging, galvanizing even, to feel that even exhaustion can be converted into energy, into life, by that shopworn old machine, literature. It's a little bit twilight, a little bit ships-in-the-night, a little bit bully-knocked-out-cold. It's always going a little dark, but that doesn't always matter.