Next year marks the 25th anniversary of 9/11 and the start of the War on Terror. The totalizing and disastrous effects of American intervention in the Middle East followed a familiar trajectory: righteous vengeance and prolonged victimhood; creeping guilt and doubt about the efficacy of increasingly cruel methods; and finally, regret if not outright shame at the destruction invoked in the name of democracy. The racism and xenophobia trotted out against America’s enemies during this time took different forms, though one moniker, that of the narco-terrorist, painted a broad but provocative picture of a Middle Eastern caricature selling opiates to prop up endless violence in the name of revolution. How ironic, then, to learn the term is better applied domestically. It turns out not only was the U.S. government subsidizing war through the tacit approval and use of drug money abroad, but that American special forces operatives were running drugs on the side, sometimes utilizing military equipment and vehicles, while also pocketing millions of dollars in discretionary funds, all without any greater or noble purpose than boredom and greed.

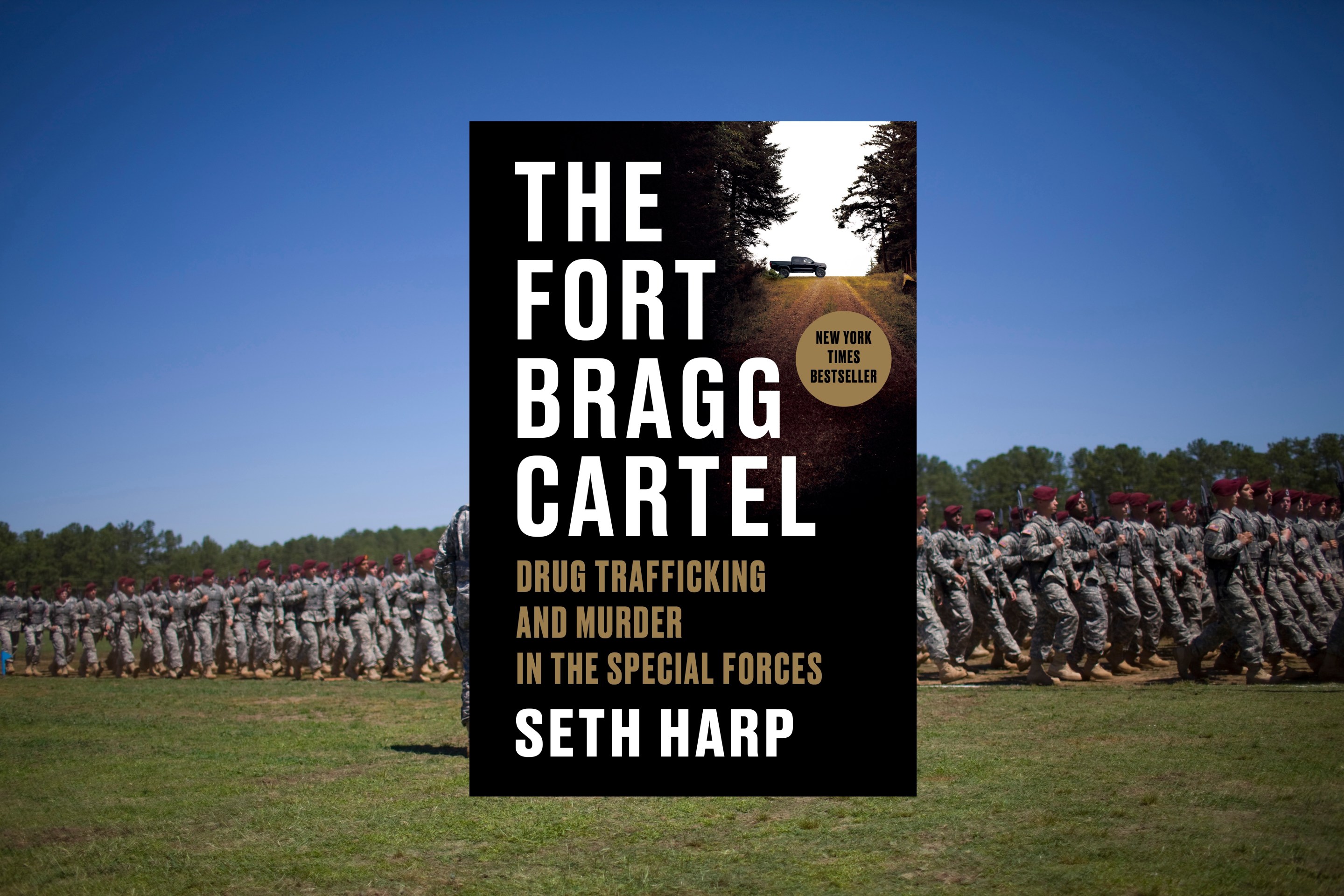

Investigative journalist Seth Harp’s book The Fort Bragg Cartel charts a pattern of suicide, homicide, overdoses, and rampant drug dealing at the titular military installation in North Carolina, which serves as a microcosm for a far-reaching dilemma of reckless behavior, violence, and addiction within American special forces organization like the Green Berets and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). Harp, who served a tour in Iraq in the mid-aughts, teases out the minutiae of Fort Bragg’s founding and importance to the training and deployment of special forces soldiers who quickly became the hidden but extremely well-funded offensive arm of the U.S. government. What exactly has the government accomplished after such a prolonged series of occupations? What patterns and cultures within the military drive soldiers to take and deal narcotics, often to deadly ends?

Harp locates the answers to these questions in the international drug trade, aided and abetted by American military personnel, active duty and retired, who took advantage of a carte-blanche, at-any-cost mindset sanctioned by presidents from both political parties. Special forces operators have been present as the spearhead of a new and profoundly disturbing era of global military engagement, with substance abuse as a rampant and growing problem at its core. The future Harp glimpses is a bleak one, where “the American way of war will be characterized, to an even greater degree than before, by the use of special operators, contractors, proxy forces, drones, spies, saboteurs, and hackers, all acting against the backdrop of an English-language media environment dominated like never before by propaganda produced by the military and State Department and disseminated by wire services, public radio, and the newspapers of record.” Running beneath it, an unsanctioned but highly tolerated breakdown that recalls the high degree of accessibility of amphetamines amongst soldiers and civilians in Germany during World War I and II.

Harp and I spoke by phone about his new book, the undertaking of his reporting, how the status quo has or has not changed under Donald Trump, and what Americans need to learn about the actions committed abroad in their name. Our conversation has been lightly edited.

I feel like a lot of American soldiers, even if they have conflicted feelings about occupation in different countries after their service, don't typically come to as robust a critical outlook as you have with your work.

There are other veterans who are equally forceful in their criticism—I’m thinking of Spencer Ackerman off the top of my head, or Roy Scranton. I also have the perspective of a lawyer, so looking at the lawless state of exception around JSOC and Delta Force and all the things that they do. It's offensive to anyone who thinks about and takes seriously constitutional law, the law of war, those kinds of things. And then also working as a war reporter, I've seen a lot more combat and been a lot closer to military violence as a journalist than I did as a soldier.

I was reading David Wallace Wells’ New York Times piece where he writes about your book, and he draws a parallel to a series of articles by Matthieu Aikins about unlawful killings by Green Berets in Afghanistan in 2012. Something I find interesting thinking about your book, and Aikins’ pieces, along with other candid reports about American intervention in the Middle East, is timing. I'm curious if you have an opinion as to why it's taken so long for there to be more honest accounts about the brutality of the occupying forces.

That's a good question. I think your question mostly has to do with Afghanistan because the extreme violence of Iraq was very much out in the open and acknowledged and understood. But the Iraq War ended pretty early on, in the 2000s. It was basically over by ’08, ’09. Obviously, armed conflict started again in 2014 with the outbreak of ISIS. Afghanistan was really in the background and on the back burner. There were just fewer people in Afghanistan. The terrain is very spread out and remote, so the sheer number of people killed was significantly less.

Most crucially, the Obama administration very effectively turned Afghanistan into a special operations war in which there were no reporters. The practice of embedding ended under Obama. You could not get a spot with U.S. troops in Afghanistan. I tried, many people tried. It was easier to embed with the Taliban. That was a big part of it, the fact that people thought, Now we have a good Democratic president. Afghanistan is the good war. There's not much going on there. All is quiet. Not hearing about it on the news, people just tuned it out.

I think what's coming to light now are revelations about the nature of the type of fighting that was going on there, the extent to which it was all about assassinations and the use of these zero units—lining people up against a wall and then shooting them—and Black Ops troops doing assassination missions a.k.a. night raids and how bad their intelligence was. That stuff just takes years to percolate out. Finally, I'll say that the collapse of the war in Afghanistan in 2021 really prompted a lot of people, including myself, to take a hard look at the war from a fresh perspective for the first time, to try to reassess it as a whole.

The bipartisan nature of American war is another theme that really struck me reading The Fort Bragg Cartel. Do you find great differences between administrations since Bush? I’m trying not to use the phrase “mask off” here.

I think that there is a qualitative difference between Trump 2.0 and the Biden administration. The way I see it, every president that has served in my adult life has been worse than the one before. There was Bush, he was the worst president in U.S. history. Then there was Obama who, for more complicated and less obvious reasons, then became the worst president in U.S. history. Specifically, because he had a popular mandate to reverse all this stuff and instead made it permanent. Then, of course, Trump came in and he was by far the worst president in U.S. history. Even worse than Obama. And then Biden came in and oversaw the genocide in Gaza. That by itself qualifies him as the worst.

But Trump is outdoing him because he's continued the war in Gaza. Unfortunately, we already used the phrase “mask off” for his first administration so now the mask is doubly off. What do you even call it when you have Pete Hegseth saying “Kill them all” to shipwrecked survivors? Which is specifically criminalized in the Pentagon's own law of war manual.

Hegseth is a figure that unsettles me for a number of reasons, but I wonder how many guys in the military are like him.

I can't really say quantitatively. There's lots of guys like him, though. Especially in JSOC. It's sometimes difficult to get a read on certain personalities and to know what distinguishes them because it's such a company-style organization and all the generals are such yes men that it's hard to know which of them actually believe in maintaining what you could call a fig leaf or a legal architecture. You know, following the laws of war and doing things by the book. It’s difficult to tell those guys from those who are just complete pirates the same as Hezbollah and terrorists and murderers.

Let's be real, attacking civilian targets to achieve a political aim is terrorism. So Pete Hegseth is a terrorist. And Admiral Frank Bradley. And the officers who carry out his orders in that regard to blow up refineries and stuff in Venezuela, they're terrorists too. They're murderers because you're a murderer if you kill someone who's unarmed. You're a murderer if you kill someone who's out of the battle or who has surrendered or who's injured. This isn’t going to happen, but you could conceive of a situation in which the political order in the United States changes and, under existing law that's already on the books, you could prosecute all these people for murder and put them in prison for life or conceivably even the death penalty under the UCMJ (Uniform Code of Military Justice). The only thing I can tell you is that the pirates, there's more of them now than ever.

This is an embarrassing anecdote, but the first time I ever heard of JSOC was in the first Avengers movie where Tony Stark says something to the effect of, “We’re a bunch of JSOC guys who have no compunction about being impolite.” But I was already subconsciously familiar with the image of a JSOC guy: a bearded white dude in a keffiyeh slinging a rifle. It’s both specific and generic. I'm wondering how you went about reporting this book and such a slippery subject.

I didn't have a set methodology. I just had the motivation to try to figure out who killed these two guys in Fort Bragg. That single-minded purpose really brought clarity to what I was doing and because one of the main figures in the book, Billy Lavigne, belonged to JSOC, I wanted to learn everything I could about it. I just read every book. It's not that hard because there's not that many books about JSOC. In fact, there’s basically only one serious work, which is Sean Naylor’s Relentless Strike. Besides that, I just got everything I could get my hands on. Every time I came up with a name, I called their house, knocked on their door. If they weren’t there, I looked up their parents, tried to talk to their siblings, spouses, exes, whatever. Everything that got swept into the book was in service of that single purpose, trying to figure out who was responsible for that murder on Bragg in 2020.

I have a feeling the answer is “no,” but did you find that being a veteran gave you access when looking into these more secretive organizations?

No.

Is there publicly available information regarding JSOC?

Depends. I can get the casualty report for a JSOC operator who dies in active duty. I was able to look at the investigations into operators who were suspected of committing crimes. I can get personnel records for JSOC operators, their enlisted record briefs. There is some stuff that's accessible, but it's not in the custody of JSOC. You can't talk to JSOC. They do weirdly have one person who's their PAO (public affairs officer), but she's not going to return your phone call. I don't know what she does.

One aspect of the book that compelled me is the strength of the prose, normally an element of true crime that’s sorely lacking, and the sense that what’s being revealed is less a matter of salaciousness than public importance. Did you have a creative philosophy as you were putting all this together?

I guess I wanted to be a writer before I wanted to be a journalist. I did a bunch of writing when I was young and unpublished. Wrote a bunch of short stories and stuff, so the quality of the prose matters to me while keeping it utilitarian and workmanlike. I've concentrated on eliminating bad prose, which there was plenty of, and my editor helped a lot with that. I think before you write well, just write not bad.

We were talking about terrorism earlier, and it struck me that the word “terrorist” feels very specific to the post-9/11 era. I felt like I was hearing it all the time through to the mid-2010s, but much less so now. I wonder if you could speak a bit about that word’s definition and how it’s morphed.

People have become so inured to hearing that word, but kind of understand, on a gut level, that it's generally deployed to describe the enemies of the United States and Israel. But it actually does have a real meaning. So when I just used it a moment ago, I think it’s important to always keep in mind: Attacking civilian targets to achieve a political aim is terrorism. The word has become this empty, Orwellian signifier that's applied to stigmatize any armed group that resists Israeli-American imperialism.

I'm curious about the afterlife of this book. I saw that HBO is going to be adapting it. I'm wondering about the conversations you had in terms of translating this material honestly on screen.

It was really important to me to be able to protect the artistic integrity of the work. We had a lot of offers, and we took the one from HBO because they were willing to let me be the executive producer of the show. So there's just one other executive producer and myself and we’re kind of in the driver's seat. HBO still has veto power over whether the series gets made, but as far as the substance of it, my team was able to ensure that I'm in a position to make sure it doesn't get inverted into some kind of jingoistic project, the opposite of the intended meaning, as often happens in Hollywood, less for political reasons than for narrative convenience.

Do you feel this current beat will become a thread you'll continue to pull on throughout your career? Or do you hope to move on to other things?

We’ll see. I haven't really come to that stage yet. As a journalist, you kind of take what comes your way. You seize upon things when you see a story where you're like, I know that's good. I certainly wasn't looking for this one. When I read that Billy Lavigne and Timothy Dumas had been murdered on Fort Bragg, I read that in the newspaper and I was like, "Holy shit." And that could just be because I knew one guy was in Delta Force and one was a drug dealer. So who knows what the next one like that will be. I can't even be sure it’ll be about the military. You’ve got to spontaneously jump on the stories that present themselves that you feel capable of tackling.