Just once! As a favor to your buddy, the food blogger on the sports website. It can be a thing we both did. A shared trial. A real bonding experience! Ready? Let's make ravioli.

Here are some things you will need:

You will need some flour, and some eggs. A fun thing to do, when you're curious to make fresh pasta, or if you just think you might enjoy the sensation of your head spinning atop your neck, is to find a handful of recipes for pasta dough, in books or online. No two of them will be quite the same. Look up a dozen; eight will use only all-purpose flour, and four will use a mixture of all-purpose flour and coarser semolina, for example. Do yourself a favor and discard the latter of these; semolina is good for dried pasta but the fresh stuff is traditionally made with regular bread flour; all-purpose is close enough.

The ratio of egg to flour, meanwhile, will, ah, vary. Serious Eats has you using two whole eggs plus four egg yolks, per nine ounces (roughly two cups) of flour. In Bill Buford's Heat, Betta, the Italian cook from whom he learns the secret dark arts of pasta-making, uses one egg per hundred grams (somewhere in the neighborhood of three quarters of a cup, loosely packed) of all-purpose flour, but the egg must be a fresh egg from a small farm, with a nearly red yolk. Also in that book, the since-disgraced celebrity chef Mario Batali uses three eggs plus eight yolks per pound of flour. La Cucina, the Italian Academy of Cuisine's invaluable compendium of Italian cooking as done by Italian home cooks, has a brain-melting number of recipes in it, and repeatedly falls back on a pasta dough recipe from Lazio, calling for two large eggs per 1.5 cups of all-purpose flour—but this recipe also asks you to include two tablespoons of olive oil, plus a teaspoon of lard. (Also Lazio's soccer team is sometimes known as "Nazio" for its supporters' political affiliations, so Lazio can eat butt!) The Culinary Institute of America, in the eighth edition of The Professional Chef, recommends four whole eggs per pound* of all-purpose or mixed flour; a pound of flour is approximately 450 grams, so this isn't so far off from Betta's ratio in Buford's book; the CIA covers the remaining liquid distance with one fluid ounce of oil.

*You'll notice, perhaps, that the CIA and Batali are both working with restaurant proportions, here; if you use a pound of flour to make ravioli dough, you are going to have enough dough to make a freaking lot of ravioli. Enough, at least, to feed 10 people.

You can view this as a bewildering pain in the ass—How will I ever know which of these is the One True Correct Pasta Recipe???—or you can view it as liberating: Clearly, there are at least several different ways to make perfectly adequate pasta dough. What all of them so far have in common are flour and eggs. You can pick any of the above ratios and you will be fine. The ones with less egg will be a bit more of a pain to work with. If you'd like me to pick for you, that Serious Eats one—two eggs, four extra yolks, nine ounces of flour—is reasonably proportioned and doesn't require the egg equivalent of the friggin' One Ring. It'll make enough pasta dough that, if you dedicate yourself to rolling it very thin, you will end up with enough ravioli for a handful of reasonably hungry people.

On the other hand! Ravioli-making, like the in many respects similar pierogi-making, is a tedious and exhausting process no matter how many you're making, and you may not ever want to do it again. So I recommend making a lot of ravioli, and freezing most of them. So maybe double the quantities? Or go for Batali's proportions?

You'll need salt. You'll need a little extra flour for dusting various surfaces and pins and such. That's it for the pasta dough.

You'll need a little bowl of regular tap water, for moistening the edges of ravioli when you close them.

Then there's the filling. Butternut squash (or pumpkin; same thing really) is a natural ravioli filling for this time of year, and also incredibly delicious. A butternut squash will be plenty; cut it into, oh, like one-inch hunks for roasting. It's not going into the ravioli all by itself, though. You'll also need to shred or grate some good Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese; if you prepare a cup of it, you probably won't use it all in the filling and will have some left with which to dress the finished product. You'll need freshly ground black pepper and a teeny tiny lil' pinch of nutmeg. You'll need extra-virgin olive oil and salt.

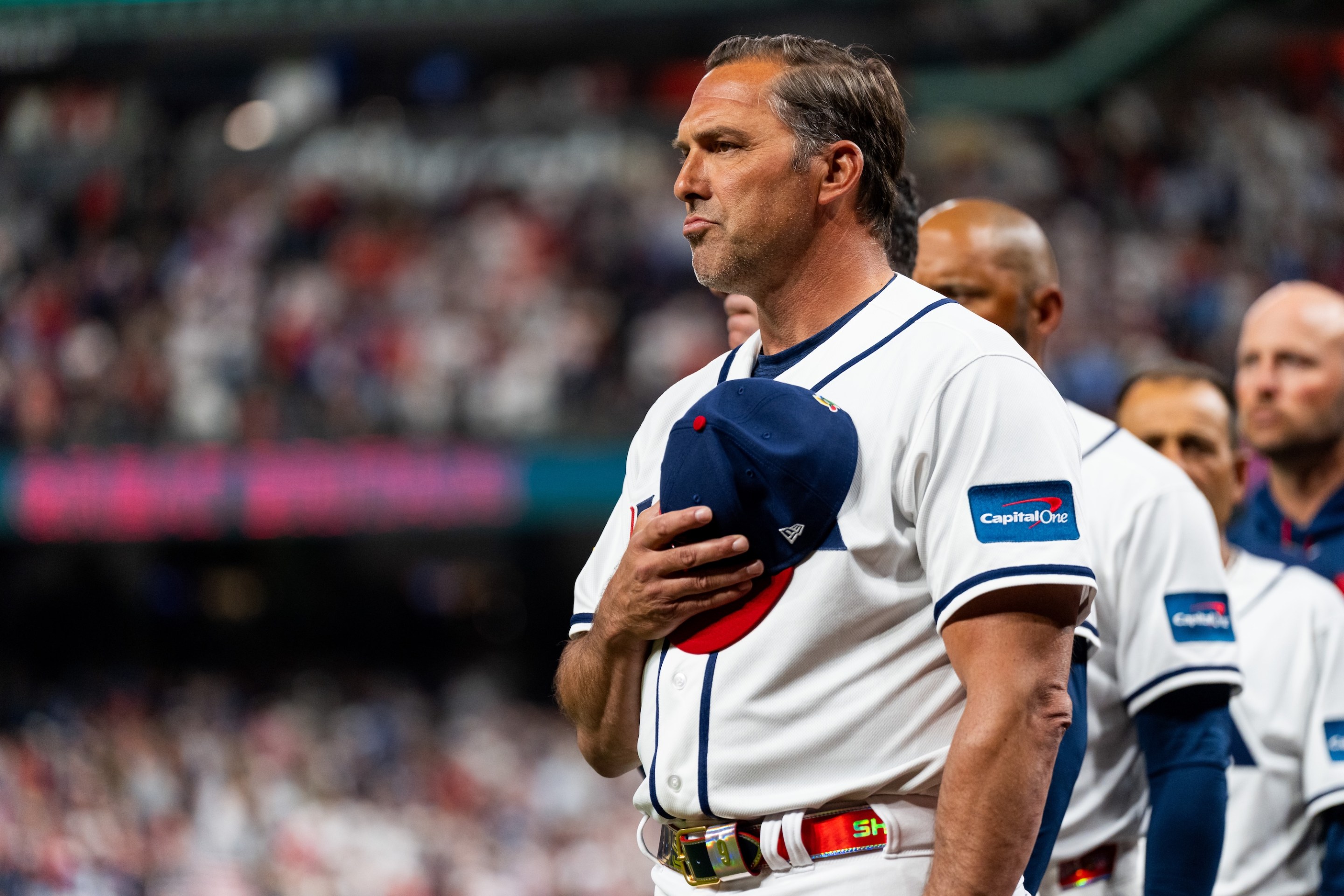

A popular and/or traditional way to serve butternut squash ravioli is with sage and brown butter. That's grand. The ravioli in the photo up there are drowning in the stuff. For this you'll need a couple sticks of unsalted butter and some fresh sage leaves. The ravioli in that photo also have toasted walnuts, a dollop of fresh ricotta, freshly ground black pepper, and a frankly immodest heaping of that shredded Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese on them. If you want that stuff on your ravioli, uh, then you will need that stuff. (Toasting the walnuts is very easy: Put some walnut pieces into a skillet over medium-high heat and shake and toss them around for a few minutes until the warm woodsy smell of their toasting has caused you to offer them your hand in matrimony.)

You'll need a wide, flat, smooth surface for working with dough, like a very large cutting board or a wide countertop or a tabletop that you don't mind getting flour all over. You'll need a rolling pin; if you feel that this must be a knob-ended Italian mattarello, suit yourself, but a regular ol' roller guy with the fat drum in the middle and the screwed-on handles on the ends is fine. You'll need a big pot of water for boiling ravioli; you'll need a flat roasting pan, maybe lined with aluminum foil, for roasting squash; you'll need a big bowl, and some sort of implement for mashing and stirring together the filling. A fork, for crimping the edges of the ravioli as you close them, would be nice, and a spoon for scooping filling into ravioli, and a knife for cutting pasta sheets into strips. I think that's it? Let's get started and see.

The first thing is to roast the butternut squash. Preheat your oven to 400 degrees. While it's heating up, toss the squash hunks with a glug of olive oil and arrange them in one layer on the roasting pan. When the oven is hot, slide that sucker on in there; check it and maybe shake it, or turn the squash hunks with tongs if you want to be dang perfectionist about it, every 15 minutes or so until the squash is soft enough to offer very little resistance to a fork, and maybe browned here and there. That should take around 45 minutes. Dump the cooked squash into that big bowl. Now add a modest fistful of the cheese, a pinch of salt, the tiny pinch of nutmeg, some black pepper, and a drizzle of olive oil, and mash this all together with maybe a potato masher or a fork or, what the hell, possibly your hands.

Taste it. Mmm. Sweet and nutty and good. Does it need more salt? More cheese? More pepper? Would the Italian Food Cops crash through the ceiling and shoot you dead if you snuck a teeny tiny lil' dusting of granulated garlic in there? Make it taste how you want it, unless how you want it includes cake frosting, in which case go to hell. When it's seasoned and cheesed and oiled how you like, cover the bowl with plastic wrap and set it aside ... for a really long friggin' time. Now you have to make pasta dough.

I'm going to tell you straight out that at first this is going to seem very tedious and annoying. I'd love to be able to follow that by assuring you that as you fall into a rhythm, it will become Actually Fun, but that would be a lie. But you can settle into a rhythm and a state of deep (and grim) concentration with it, and this makes it endurable. And then when you are done, nothing will ever make more sense to you than the fact that people invented machines to make pasta for them.

OK. So. Let's make pasta dough. I'm not going to boldface the individual steps in this part because that would be ridiculous. Pile the flour into a lil' heap on your flat surface. A cute little mountain of flour. You're going to turn this mountain into a volcano—not by exploding it, or by putting baking soda and vinegar in it, but by using the heel of your palm to press a little crater into the top. Like a well.

Into this well go your eggs (without their shells!) and your extra egg yolks, and a pinch of salt. With your fork, gently—so as not to collapse the sides of the well, which would cause the runny egg to go all over the friggin' place—whisk the eggs in the well, to scramble them. As they gradually go from yolks-and-whites to homogenous scrambled egg, you'll also be pulling in little amounts of flour from the sides of the well, whether you intend to or not; do this a very little at a time, on purpose, and you'll see the egg gradually transforming into something thicker and stickier. Once it's thick and sticky enough that you're sure it isn't a threat to run anywhere—you can switch to a silicone spatula if the fork gets too annoying around this time—go ahead and start incorporating the flour from the well more aggressively, until it's pretty much all in there.

An infuriating thing that pasta recipes do at this point is they refer to the mixture of flour and egg as a "ball" of "dough." It likely will not seem much like a "ball" at this point, and may not even seem all that reminiscent of anything you'd call "dough," either. It very well might seem alarmingly dry to you, and you will be standing there thinking to yourself, Oh God, it's supposed to be a doughy little ball and I've fucked this up, there was some article of ancient ingrained Italian Knowledge I had to have possessed by this point and I did it wrong and now what, should I just like sneak another egg in there? It's fine! It's fine. You don't need to sneak another egg in there. You just need to beat that dang wad of flour and egg up a little bit.

Form the ... the mass ... into as ball-like a shape as you can manage. Now, on your floured surface, press down hard into the center of the mass with the heel of your palm. Really put your weight onto it! Flatten that fucker! Now sorta rotate it maybe a quarter-turn, and repeat. And repeat. And maybe reform it a little, and repeat. And repeat. And reform it a little, and repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat repeat repeat repeat repeat repeat.

It's miserable! I'm very sorry. But as you do this, you will start to notice something. Somehow, in some weird way, this clump of flour and egg will start to seem moister through this repeated action of smushing it with your hand. That doesn't seem like it should be possible—you're not adding more liquid to it, after all—but it happens anyway. It'll start to seem warmer and stretchier and smoother, too. It'll start to seem like ... dough! When it's finally smooth and stretchy and feels like something you could mold into shapes, form it into a neat ball, wrap it tightly and completely in plastic wrap and set it aside on the countertop for half an hour. That's plenty of time to write a rude email to my editor requesting that I face you upon the field of combat.

There are Science Reasons why the dough needs to rest. For all that you accomplished by kneading this stuff with your bare hands, at this point it is still mostly just some egg and some flour, trapped next to each other. During the resting period, the flour particles will absorb the egg liquid and the gluten in the dough will relax, so that when you roll it out, it will more readily settle into the thinness you want, rather than tearing, or snapping back to its original shape. And let me tell you, buddy, both of those latter two outcomes are extremely fucking infuriating! So let your dough rest.

Has your dough rested? OK. Let's make ravioli out of it. This is the most tedious part of all. I promise to try to get through it quickly here.

If you had a genuinely huge surface, and a really incredibly wide rolling pin, maybe you could roll the whole entire ball of dough into a flat pasta sheet all at once. Unfortunately, if your life is anything like mine, you do not have a 92-foot wingspan, so you will have to do it in portions. Station your bowl of ravioli filling nearby and plop a spoon into it. Also the little bowl of water from way back up in the ingredients portion of this endless blog.

Scatter a little flour across your work surface; rub a little onto your rolling pin. Tear off a quarter of the dough ball and roll it into its own little ball with your hands. On the work surface, press the rolling pin down on this little ball and roll back and forth a few times until it's a flat oblong, then turn it 90 degrees and roll it a few times that way so it's more of an even shape. Repeat this process, pressing down progressively harder, until the dough ball has been turned into probably a pretty irregular and mutated but very flat and thin shape. Can you make it any thinner? Please try. You do not need to be able to read a book through the eventual sheet of dough, but the thinner it is, the more ravioli you'll get out of it.

It's not going to be some shapely flat circle, or rectangle. It's going to be a bizarre abstract shape. You will not be able to look at this thing and easily visualize some number of discrete ravioli that will come out of it. That's fine.

Now. In theory you could maybe use the rim of a glass or aluminum can to cut out neat circles for your individual ravioli, but then there's going to be a bunch of leftover dough from between the circles. What I recommend is using a butterknife to cut this big flat sheet of dough into long strips, two or three inches wide. On one strip of dough, plop little roughly tablespoon-sized blobs of filling, with an inch or so of space between them. Lay another strip of dough atop this. With that knife, cut the ravioli apart in those areas of space between the lil' heaps of filling. Wet the edges of each raviolo with your fingertips (using the water in that little bowl from way back up there) and pinch them together, then use the fork to press down around the perimeter for a nice tight seal and a sweet-looking pattern.

I pride myself on not allowing cooking steps to seem much easier in the blog than they will be in practice. If the procedure in the above paragraph did not sound like a pain in the neck, I have failed. It's a pain in the neck! No two of your strips may be the same size; the filling may try to poop out the sides of the ravioli as you close them; the dough may start to get dry if you don't work quickly, making sealing the ravioli a tricky job. None of that is unusual; none of it means you are doing anything wrong; none of it precludes the finished product making anyone who tastes it groan and roll their eyes around as though experiencing an NC-17 rated form of ecstasy. Just keep working.

When you've turned as much of this first hunk of dough into ravioli as you can, set those ravioli aside (on a sheet of aluminum foil maybe?), tear off another hunk of that dough ball, and repeat. This is where it really helps to have a team: Somebody can roll the dough, somebody can cut it into strips, somebody can plop filling on there, somebody can separate and seal the ravioli. This can make it a not-totally-unenjoyable group activity, rather than a grim march of death.

My hope is that after a while you will have turned that initial ball of dough into a lotta frickin' ravioli, instead of being like Fuck this and fuck you and finding something else to do with your day. Assume an adult may eat up to six of these in one go if they're dressed with butter and cheese and nuts and do the math on how many you'll need today; the rest can be frozen on a sheet pan until they're hard and then socked into a sealed heavy-duty Ziploc-type bag and stored in the freezer for months. Shall we cook up the rest and eat them? Hell yeah we shall.

Melt the unsalted butter in a skillet over low-ish heat. Then just kind of hang out with it for a while, while you put the big pot of water over high heat to boil; after a little bit, the milk solids from the butter, which have settled to the bottom of the skillet, will begin browning. At this point, toss the sage leaves in there so they can make the butter taste and smell good; once the butter has taken on a deep toasty brown color—but before it burns black!—turn the heat off.

If you time this right, the butter will finish browning around the time the water comes to a boil; the ravioli, being freshly made, will not need more than maybe a minute of boiling. Boil the ravioli! I recommend doing this in batches and removing each batch from the water with a long-handled wire spider or mesh strainer before adding the next. They're very delicate, and they won't like being dumped through a colander.

Here's a good way to do this: Boil two people's servings of ravioli, extract them from the water, very gently toss them with some of the browned butter in a bowl, then slide them onto a pair of plates. Dump the next batch of ravioli into the boiling water, then return your attention to the plates; top each with a handful of toasted nuts and some of that shredded or grated cheese (and maybe a blob of smooth ricotta if you went that route) and crack some black pepper on there; by the time you're done with that, the batch of ravioli in the water should be done boiling. Repeat this pattern until they're all cooked. Then it's time to eat.

You put up with like 9,000 paragraphs of winding instruction on how to make ravioli; you don't need 200 purply words on what the fuck they taste like. Eat the damn ravioli!