League Anti-Violence Policies Are Just A Smokescreen For Owners

6:28 PM EDT on August 29, 2021

This past Friday, the day every organization likes to dump its bad news, MLB confirmed it was, once again, extending Trevor Bauer's administrative leave. The Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher has been on leave since July 2, a few days after news broke that a woman was seeking a long-term restraining order against him after she told a court that he assaulted her twice and Pasadena police were investigating. A judge decided on Aug. 19 to not extend the woman's restraining order, but the legal process still brought plenty of horrifying details about Bauer's conduct into the public light. Now Pasadena police have turned over their evidence to prosecutors, to let them decide if a criminal case should be pursued.

Amid all this, it can be easy to forget why MLB had to put Bauer on administrative leave in the first place—the Dodgers themselves were not going to bench Bauer. As has been pointed out before, a team can bench a player at any time for any reason. Yet the Dodgers leadership felt they needed to defer to bureaucracy on this one, which you can argue is also a way of avoiding their own agency in the matter. It also obscures the entire reason these player conduct policies exist. It's so that the most powerful people in sports can keep fans forgetful of how much power and say they actually have over all of this.

And it began, like with Bauer, with a famous athlete accused of intimate-partner violence.

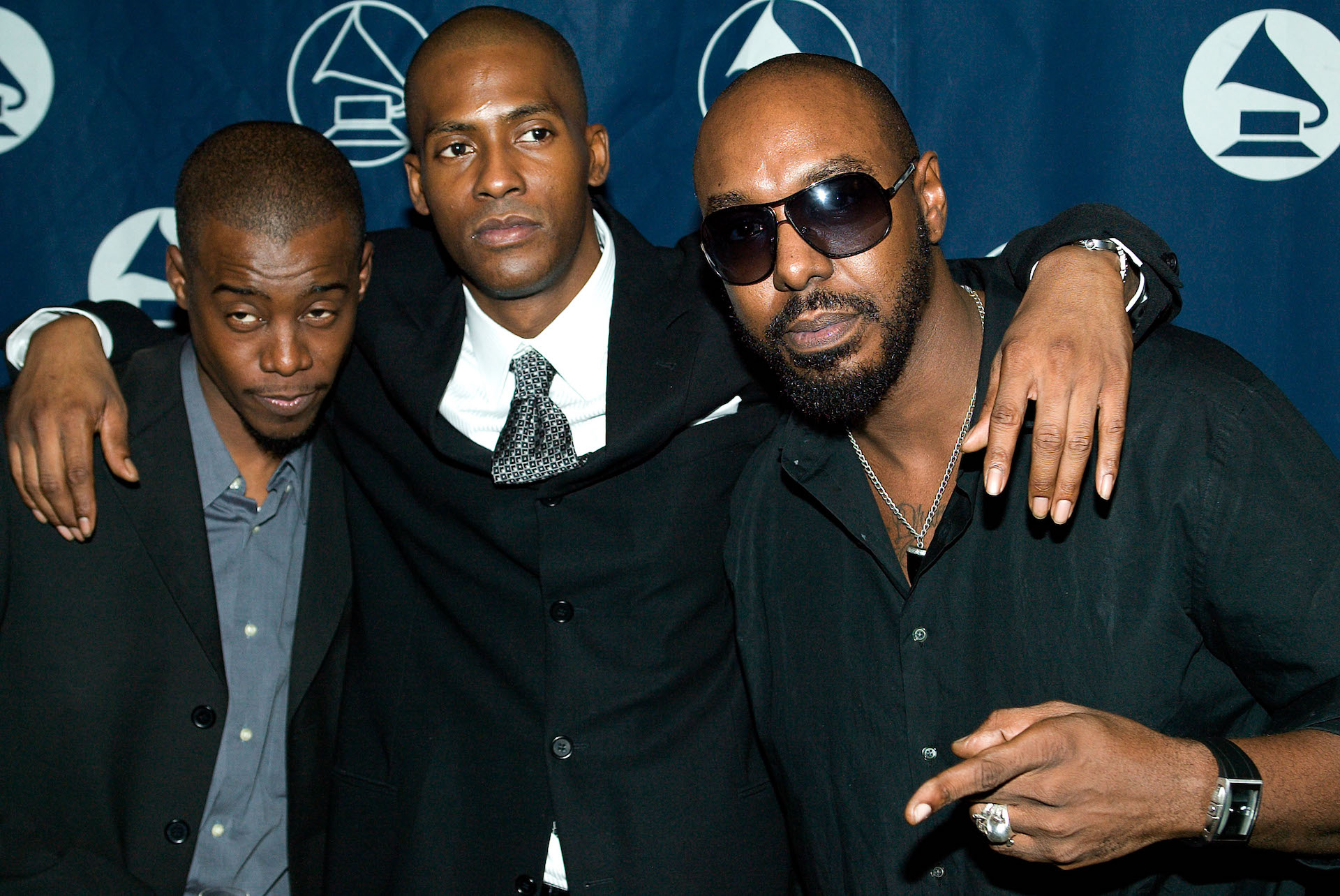

In July of 1995, Warren Moon was easily one of the most famous players in the NFL due to a combination of his spectacular skills and the endemic racism he had overcome to even convince the league to give him a shot as a starting quarterback. The depths of the entrenched racism toward black men who wanted to play quarterback in the NFL is hard to overstate; one of Moon's own teammates compared Moon's leadership in the huddle to that of César Chávez and Martin Luther King Jr. He would go on to have a Hall-of-Fame career and become the first black quarterback, as well as the first undrafted QB, enshrined in Canton.

That July, law enforcement investigated Moon for intimate-partner violence. His wife told Houston police that Moon hit and choked her, but she did not want charges pursued. A criminal case was brought anyway—it's always worth remembering that it is, ultimately, the state and not victims who decide if an investigation happens and if a charge is filed—and a Houston jury acquitted Moon. But by then, the issue of intimate-partner violence in sports had spread far beyond just Moon. Weeks after the Moon case became public, Sports Illustrated ran a story calling intimate-partner violence sports' "dirty secret." The LA Times ran its own special report on violence against women committed by athletes in December. In between, former NFL star O.J. Simpson was acquitted of the murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson in one of the most-watched trials of the century.

Moon's team, the Minnesota Vikings, did not suspend him. In July, then-Vikings president Roger Headrick told the Star Tribune, "We're not talking any discipline, we're not talking any punishment; what we're interested in is seeing if we can help them get their life back in a condition that they can deal with one another and go forward." But was that really going to happen when the Vikings also were the team where the head coach and his assistant had been accused of sexual harassment? With pro-criminalization policies sweeping the country—especially those, like the 1994 crime bill, that sold themselves as getting tough on violence against women—it's little surprise that the NFL saw all this reporting on violence by its athletes and perceived an opportunity.

In late 1990s, the NFL unveiled its anti-violence policy, the first in North American pro sports. Longtime NFL executive Harold Henderson told the Kansas City Star in 1998 that the policy didn't need to be collectively bargained because it fell under the commissioner's jurisdiction. The owners, no surprise, approved of this. Then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue was honest about the policy's intention. It was not to provide any sort of healing or support. It was about how the NFL looked. Here is what the Toronto Star reported Tagilabue said soon after it passed.

''Too many fans today perceive sports leagues, teams and players as irresponsible in their conduct both on and off the field. . . . We want to help the players keep out of trouble and we think this is one way to do it,'' he said.

The policy did not keep any players out of trouble. That didn't stop other leagues from copying it anyway. Because it was, after all, great PR.

I have echoed Natalie Weiner's brilliant observation before, but it's worth repeating: "Without looking at systemic sexism and violence holistically, you wind up playing Whack-A-Sexist with required performative contrition as a mallet." In the case of pro sports, then factor in who is being asked to be holistic: gaggles of ruthless billionaire owners who do not care about climate change, or from whom they steal, or when tragedy happens at their own companies.

These personal conduct plans, ultimately, are exactly for a situation like Bauer. It's so teams and their ownership can put up their hands and exclaim, There's nothing we can do, with a straight face. At this point, these policies have become so ingrained that reporters parrot them back and write as if they are a forgone conclusion, as if they must exist with the same certainty as a football field being 100 yards and the distance between a pitcher's plate and home base being 60 feet, 6 inches. But there is nothing that says they must function this way or exist at all.

People like to ask me what leagues should do, and I know the answer they want: Here is the policy that leagues can pass to make everything better, to make all this go away, to make everyone feel good about how this is being handled. But I'm not sure the answer starts with policy. To me, it would have to start with dialogue. Ask spouses, partners, and family members what they need, how they can be better supported, and what a team should do and should not do when violence happens. Except I cannot fathom such a dialogue happening and that is, perhaps, where the dark heart of all this lies. The answers start with such a basic modicum of human decency—listening—and it's the one option I cannot fathom any team owner ever taking.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Investigations Editor. You can reach her at diana@defector.com or, if you prefer protonmail, dfmoskovitz@protonmail.com. If security is a concern, download the Signal app and send her a text at 929-251-8187.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter