The Cambrian period is most famously remembered as an era of biological experimentation, with bizarre creatures such as Hallucigenia, whose body resembled anti-bird spikes, and Wiwaxia, which looked like a medieval flail come to life. But the Cambrian should also be remembered as a time when shit got extremely real for fish. If life in the oceans seems scary now for anything small and soft-bodied, they were undoubtedly scarier 518 million years ago in the Cambrian period. For eons, the oceans belonged to filter feeders, which raked in plankton and other animalcules rather peacefully (for everyone except for the plankton, of course.) But over time, the oceans gave rise to large, carnivorous predators, which meant little fish needed to adapt if they were going to make it out of the Paleozoic period alive.

Myllokunmingiids, the earliest fossils that look anything like fish, were discovered in China and hail from around 518 to 530 million years ago. One species of myllokunmingiid called Haikouichthys was, scientifically speaking, just a little guy, topping out at about an inch long. Like a modern fish, Haikouichthys had a head, a modest array of slits that looked like gills, and a distinct muscle-bound spine. Unlike modern fish, it lacked a jaw. Instead of a modern fish mouth, it had a conical opening like that of a lamprey or hagfish. It didn't have much in the way of fins, either.

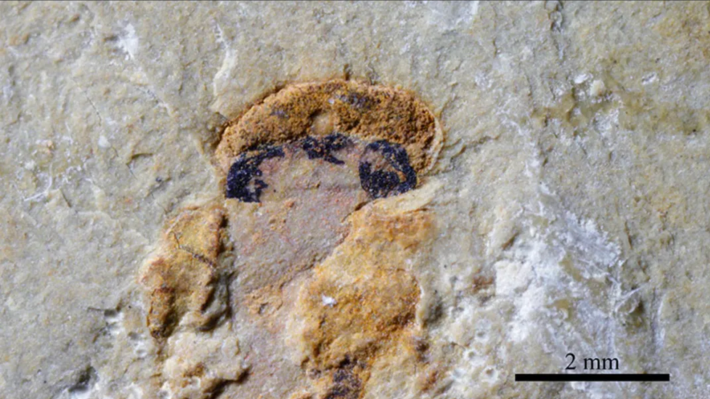

Now, a new paper in Nature suggests that Haikouichthys diverges from modern fish in another key way: Instead of two eyes, Haikouichthys had four. The authors, a team of researchers from China and the United Kingdom, examined some exquisitely preserved fossils and found Haikouichthys and another myllokunmingid had two larger eyes outside their heads and two smaller eyes in the middle of their heads. All four eyes contained melanosomes, organelles that produce and store melanin and control coloration and light absorption in eyes.

"We started by examining the obvious large eyes to understand their anatomy—and it was a complete surprise to find two smaller, fully functional eyes between them," author Peiyun Cong of Yunnan University said in a statement.

These four eyes gave Haikouichthys some clear advantages, including a wider field of vision that would have helped them dodge predators. The second pair of eyes were not just simple light sensors, but rather sophisticated organs that could translate the world into images. The researchers suspect the second set of eyes were the precursor of the pineal gland. This gland helps us regulate sleep by producing melatonin when it gets dark. But in some fish, amphibians, and reptiles, the gland still detects light.

Here, I propose another, alternative advantage these third and fourth eyes conferred unto Haikouichthys: Capturing the sheer terror of being alive.

It is famously hard for fish to communicate emotions, or whatever equivalent exists for them. We cannot understand the sounds they make. They cannot smile or make any facial expressions recognizable to us. For centuries, people have dismissed fish as alien and simple. "Fishes, but not other vertebrates, are repeatedly asked, in increasingly elaborate experiential designs, to prove that they can feel pain," the animal scholar Becca Franks wrote in the anthology Animal Dignity.

There is a growing body of evidence that expands what we might describe as the inner lives of fish. Research suggests fish can learn, remember, and experience pain. They have complex social relationships and use tools. I wager that Haikouichthys's second, smaller set of eyes, made flesh by this artist's reconstruction, would prove a powerful tool in our modern grappling with fish sentience. It looks like a smaller face that is experiencing the terror familiar to so many of us, which is to say the inescapable anguish of being alive on this planet. Who amongst us cannot relate to this little fellow?

Perhaps if we imagined that fish, too, experienced existential dread, we would be less likely to kill them brutally en masse in the commercial fishing industry. Perhaps if we speculated that fish, too, knew the horror of being in a fragile, mutable, and corruptible body, we might extend them some grace in our considerations of their welfare. Perhaps if we envisioned a world in which fish, too, grappled with their own mortality, we might treat those around us with a little more empathy. Let Haikouichthys be a reminder that we are not alone to weather the angst of worldly threats, the panic of uncertainty, the trembling of great fear, or the torment of despair. And that sometimes the only thing to do is scream!