Every so often, an obvious talent will suddenly appear from nowhere. The initial instinct, among critics, is to indicate this event as an event via a rush of comparisons. One such case was that of Elisa Shua Dusapin, 24 at the time of her debut novel, and 29 when her work reached English-speaking audiences. Dusapin was immediately inducted into a number of artistic lineages that all forecast some future importance. Dusapin writes a distinct type of novel—roughly 150 pages of sparse and haunted prose—that netted her comparisons to interdisciplinary titan Marguerite Duras; perennial Booker Prize competitors including Michael Ondaatje, Deborah Levy, Elena Ferrante; and a note from the publisher evoking Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux. International praise evokes all-timers the likes of Henry James, and Anton Chekhov. Dusapin traverses the same banal dreamscapes made famous by filmmakers like David Lynch or Yorgos Lanthimos (in their less hostile moments), where everything seems perceptibly wrong. Dusapin is also a truly international writer, born in France, and raised between Paris, Seoul, and Switzerland, she currently lives in Jordan’s capital city, Amman. Her books have now been translated into 35 languages, and she won the 2021 National Book Award for translated literature. The forecasting was correct, and she really does have a gift.

Like the international cities she has called home, each of Dusapin’s novels is distinct, but united by her astonishing, borderline-generational talent for mood and atmosphere. The range of emotion is extensive, from the thrumming disquiet of her breakout debut, Winter in Sokcho, to the minor-key sadness of The Pachinko Parlor, to the simmering tenderness of Vladivostok Circus.

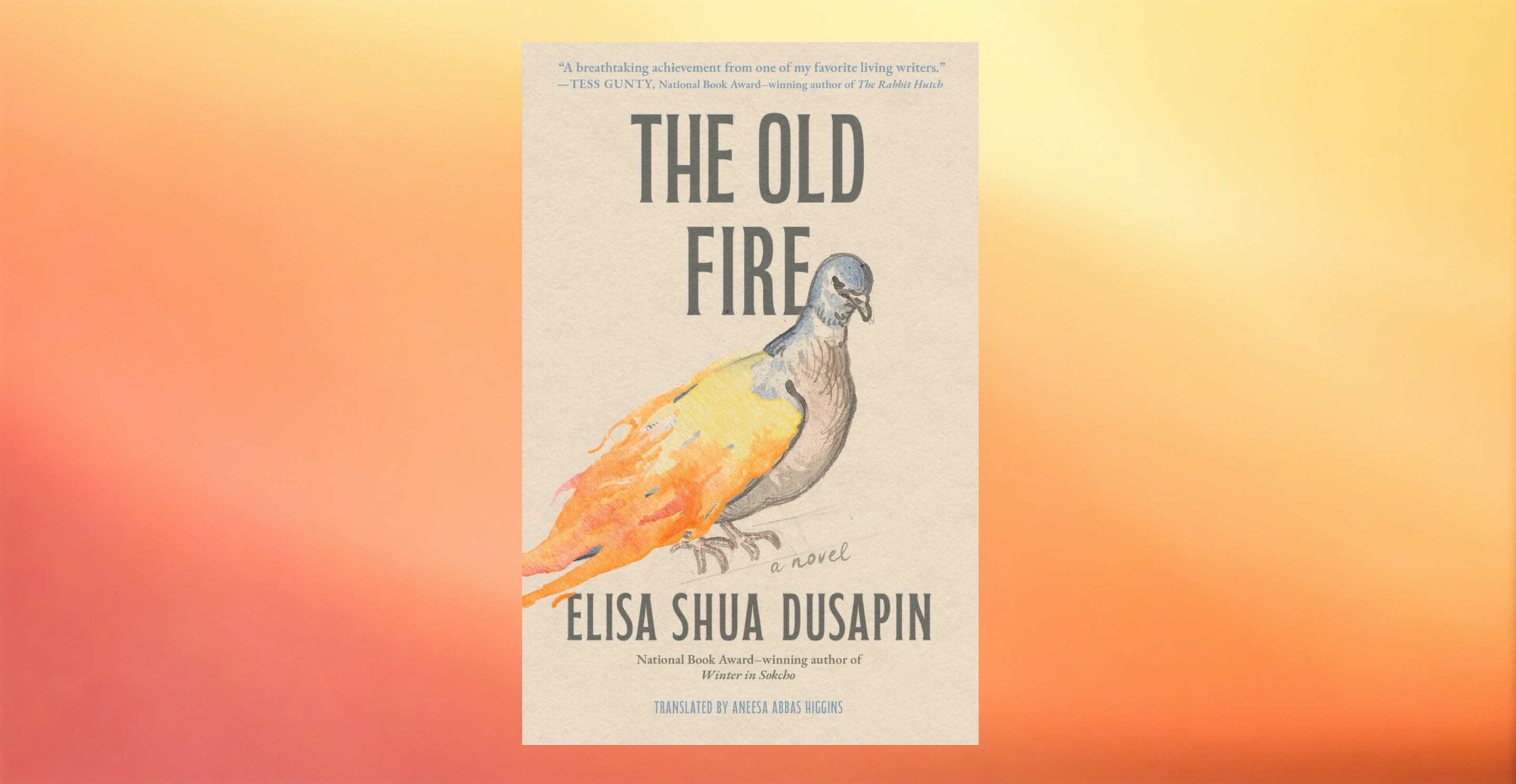

These three novels form a sort of unofficial trilogy, all appearing in excellent translations from the original French by Aneesa Abbas Higgins, and were published by Rochester-based press, Open Letter. The Old Fire, Dusapin’s fourth novel, reaches a sort of synthesis of the three prevailing moods that have appeared in her novels thus far.

Arriving via Summit Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster, and again translated by Higgins, The Old Fire is Dusapin’s first outing with Major League Publishing, but remarkably sacrifices none of the things that earned her such devoted readership. Despite sharing a publisher with bestsellers and celebrity memoirs, The Old Fire is not necessarily a piece of commercial fiction, and in many ways, outright refuses to be.

Dusapin’s novels have very distinct settings, and Old Fire continues this trend, but she is interested in the spaces online essayists love to call liminal. Her work has been set on the border of the two Koreas, amid the sprawl of contemporary Tokyo, the isolated Siberian city of Vladivostok, and now, a strange half-burned house in the French countryside. Beyond a physical sense of the in-between, she is preoccupied by the space between past and present, and between human beings. Largely devoid of plot, her books are so unique in setting, and so precise in their emotional register, that they prove unforgettable even if little “happens” in them.

In this way, Dusapin often avoids the common practice of subverting expectations by simply refusing narrative convention altogether. Winter in Sokcho, for example, ends at exactly the moment where another, longer book would see the plot begin in earnest. Similarly, The Old Fire has all of the trappings of a classic family saga, but stays almost entirely in the present moment, letting the family history and traumatic backstories exist as if behind a locked door.

Our two principal characters are Agathe and Véra. Agathe is a screenwriter, who has left France to live in New York and hasn't seen her childhood home in 15 years. Véra stayed at home to take care of their aging father, and to let her father take care of her. After a decade and a half of semi-estrangement, Agathe returns home to rural Périgord, a region of France east of Bordeaux, to help her sister clean out their childhood home after the death of their father. The house, in which Véra still lives, was partially burned in a fire, and has been slated for demolition.

From there, the book unfolds in a state of rain and perpetual twilight. Dusapin’s knack for atmosphere is on full display as she renders the early November. Here, the reddening leaves appear as miniature hearts escaped from their rib cages, as the wind “blows up against the front of our house, rolling over like a swimmer turning in a pool.” Her descriptive prowess continues as the sisters traverse the minefields of memory attached to places and objects. In town, while the sisters are shopping, Agathe lags behind her sister. “Most of the shutters are closed,” she notes. “Outside the church I notice the recesses at the base of the wall. A sign explains that these are the sarcophagi of children who died in the womb, or didn’t live long enough to be baptised. The sign wasn’t there when I lived here.” The scene ends with Agathe comparing her sister to dust, trapped beneath the eyelid, her body trying to wash Véra out with tears.

Dusapin conceals a good look into the past that has made these relationships so complicated. Instead, as the sisters pack photographs and articles of clothing, we are shown a collage of feelings and flashbacks that create a breadcrumb trail through their history. In one especially poignant vignette, Agathe finds a photo of their mother, dated 10 months before she was born. “My mother. But not yet my mother,” she thinks. Neither sister has heard from their mother since the death of their father. The implication is that a photo of this same woman would now show someone who is their mother, but no longer their mother. She left the family when the girls were young. She lives in London, happily remarried, as if none of it had ever happened.

In another scene, Matryoshka dolls and glassware, dismissed as “bric-a-brac from Eastern Europe,” are revealed to be gifts that Agathe and Vera’s mother had purchased for them. The mother, we then learn, was the breadwinner for the family. Their father had spent all of his money, and all of his free time, maintaining the house. Their father’s steadfast and pragmatic nature is slowly understood as a mask that he wears to hide feelings, and perceived shortcomings, as a single father and the lower-earning parent.

The dynamics between characters are felt more than they’re ever explained. Véra developed aphasia when the two were children, and hasn’t spoken in two decades. In the present, she communicates with her sister by typing out messages on her phone. It gives even the most basic communication a stilted pacing that effortlessly implies the reserve with which the sisters regard each other at first. Similarly, after so many years apart, the sisters are not used to their shared history and refer to their parents possessively, saying “my father” or “papa” before gradually shifting into the communal “our.” At one point, Agathe states it bluntly, saying: “I force a smile. I find it hurtful when she talks about her life with my father without me.”

Elsewhere in the sisters’ present, we learn that Agathe has had an abortion, which she has kept secret from her partner until the bleeding becomes too serious to conceal. This detail is also kept from the reader until the moment in the book when it becomes seemingly unavoidable.

This attention to language is sharpened to incredible effect as Dusapin exacerbates disconnection and discomfort at almost every turn. Beyond cleaning out the half-burnt house, Agathe conducts meetings over email and Zoom—straddling time zones and relationships between the two phases of her life. Véra is a botanist, attempting to alter the DNA of flowers so that they bloom forever. The dissonance is intentional, however frustrating it may be.

The veiled nature of Dusapin’s storytelling is most evident when the moment of fallout—the untimely death of a kitten the family had recently brought home—is finally revealed. But even the key details of this grand reveal are left somewhat ambiguous. The death is assumed to be Véra’s doing, a moment of unexplainable cruelty, which occurs after Véra has stopped speaking. We never see the moment of the pet’s demise, only its aftermath. Véra is blamed, but Véra is also unable to explain, or defend herself. As with the death of the father, their absent mother, the numerous explanations for Véra’s aphasia, Dusapin is less interested in the events that affect her characters, than in the fact that they have been affected. The drama is not something contained in the past, but, like time itself, is always unfolding.

The Old Fire is a masterpiece of restraint. A book that deals in sensitive subjects, but eschews void-gazing and bloodletting to craft a truly unique approach to grief and trauma, even in the moments when actual blood is involved. These ambiguities are a risk in the landscape of contemporary literature, but it’s a risk that will pay off for readers who enjoy sitting with something after it has ended. Dusapin’s status as a rising star of the literary world was evident immediately, but with The Old Fire she demonstrates an ambition beyond her talents for mood and atmosphere. Turn your attention to the bigger pictures, and you will be rewarded with a reminder that like a body, or a house, our lives are lived within our history, not alongside it.