Last week in Nature, scientists described an absolute doozy of an ancient cetacean: a 39-million-year-old creature called Perucetus colossus that they say may have weighed somewhere between 85 to 340 tons (187,000 to 680,000 pounds). If the most extreme estimate is true, Perucetus would easily topple the blue whale as the reigning titan of heft. Blue whales, which can grow to 180 tons (330,000 pounds), are the heaviest animals known to ever exist. And even more impressively, Perucetus was only about two-thirds the length of a blue whale, meaning its body may have been laden with flab.

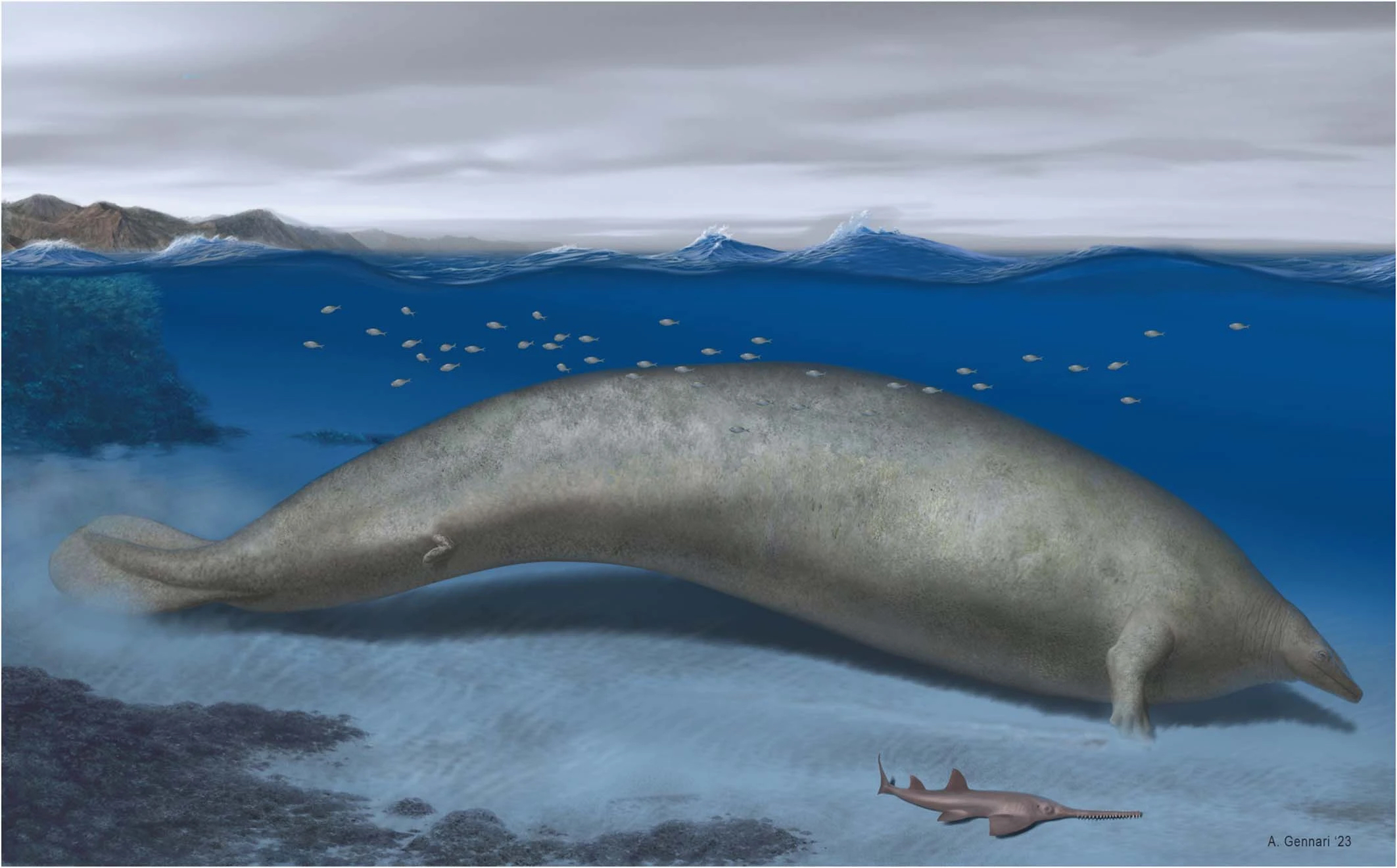

The researchers discovered a fraction of the fossilized whale in a desert in southern Peru, unearthing a bit of a pelvis, four ribs, and 13 vertebrae. But the paper also included a hypothetical reconstruction of Perucetus that suggested the whale resembled a swimming bratwurst tapering into a vanishingly tiny, crocodilian head. It is a beautiful illustration depicting a rather silly-looking creature, raising the timeless question that plagues all paleoart: Why does it look like that?

All paleoart is speculative—a blend of often-evolving scientific hypotheses and artistic interpretation in pursuit of helping people visualize what life looked like millions of years ago. Few fossils are found in their entirety, and many species are known only from scarce bone fragments, meaning that some paleoart involves more educated guesswork than others. The process behind these reconstructions is not always obvious to the public, so I asked one of the authors of the paper and Alberto Gennari, the scientific illustrator behind the image, to break down how a part of a pelvis, some ribs, and 13 weirdly thick vertebrae became the vastly chubby animal you see on this page.

In the case of Perucetus, "a big part of the reconstruction is speculative," Eli Amson, a paleontologist at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in German and an author on the paper, wrote in an email. The missing bones, as well as the fact that Perucetus's bone morphology strays significantly from modern mammals, make it hard to make precise conclusions about what the whale would have looked like, Amson explained. "We work with what we have," he said.

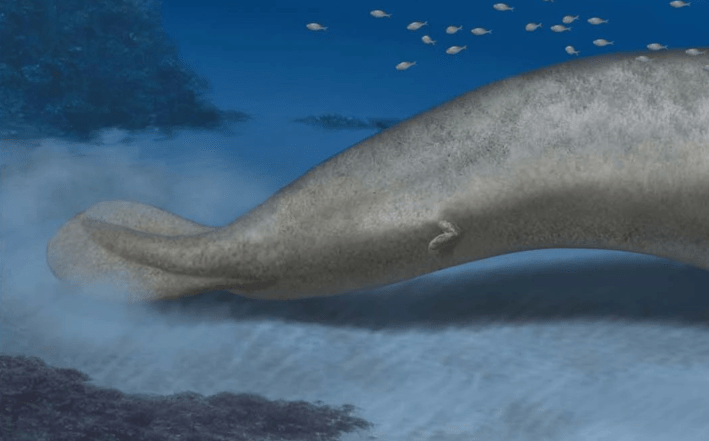

First, the researchers had to fill in the rest of the ancient whale's skeleton. "The missing parts of the body are based on a close relative for which a complete skeleton is known, which was scaled up to match Perucetus's size," Amson said. The close relative, Cynthiacetus peruvianus, is an extinct early whale that lived in what is now Peru in the Late Eocene, around the same time as Perucetus. The nearly complete fossil skeleton of a young adult C. peruvianus reveals the animals had small hindlimbs and forelimbs—too small for walking, but dangling there nonetheless. So this explains Perucetus's wee little limbs.

But this does not answer perhaps the most pressing question about the restoration: Why would Perucetus have such a laughably small head? The ancient whale's head is also based on C. peruvianus, Amson said. But the vertebral bodies of C. peruvianus are surprisingly shorter than the vertebral bodies of other early whales in the same family, Amson said. Perucetus has longer vertebral bodies than C. peruvianus, which would indicate that its body was also more elongate. "An even more extreme condition of elongation of the vertebral bodies is seen in Basilosaurus, where the head was also ridiculously small," Amson said. So Percetus's elongated vertebral bodies would suggest its head would also be ridiculously small.

Tiny head aside, a reconstructed skeleton does not obviously shed light on the flesh that once surrounded it. Why does the reconstruction depict Perucetus as a girthy banana as opposed to a svelter swimmer? This hypothesis, Amson explains, was informed by the composition of the ancient whale's bones. Perucetus's bones were thick and strangely rock-like, far denser than the spongier bones typical of mammals. Each of the 13 vertebrae weighs over 220 pounds. And the bones showed signs of pachyosteosclerosis, a condition where bones thicken with extra layers and fewer cavities. These heavy, compact bones can help mammals such as modern manatees regulate their buoyancy while grazing in shallow waters. So a manatee served as "the major guide for the overall appearance, including the body shape and fluke shape," Amson said.

Without a trace of a skull or teeth, the researchers do not know what Perucetus would have eaten—if the creature fed on sea grass like manatees, scavenged for carcasses, or sifted through sand for clams. Everyone seems to agree that Perucetus was far too thick to catch anything that could swim. So the sawfish Gennari drew next to Perucetus, a species that was excavated nearby in Peru, would have no reason to fear its gigantic companion (except, perhaps, the fear of being mightily squashed).

Any paper this big is not without its skeptics. A scientist not involved with the paper expressed doubt about the higher-end estimates of Perucetus's weight. But the researchers are not claiming Perucetus was heavier than a blue whale, just suggesting it may have been. Amson believes the reconstruction is "very conservative" in regards to the overall body shape and what he calls the "degree of chubbiness," and added that his team might attempt to more accurately estimate the volume of soft tissue on Perucetus. A 400,000-pound whale can be associated with different volumes, depending on how much of its soft tissue is fat versus blubber or muscle. "I can foresee that the result will be even weirder than what we see in the current reconstructions," Amson said. Weirder, in this case, might mean an even girthier Perucetus, according to Amson's preliminary calculations.

When the scientists created a sketch of their best approximation of Perucetus's shape, they sent it to Gennari, suggesting the whale may have swum in the shallow and fed near the seafloor. "Just looking at the shape drawn by paleontologists, I thought that this animal looked like a huge sausage with fins," Gennari said.

But in all Gennari's scientific illustrations, he thinks about the emotion and responsibility of giving "life" to a fossilized animal or plant that is "often reduced to a pile of petrified remains, unattractive and difficult to understand for the great public." And it's also a detective-like task that involves copious research—studying photos of modern animals, learning about anatomy, and even studying prehistoric botany. So, sketch in hand, Gennari worked to bring the strange whale to life. "I covered the body with patches of algae, encrustations," Gennari said. "I imagined a color similar to that of the sands of shallow waters, and I placed the beast in shallow water, on a windy day along the Peruvian coast."

Other paleoartists have already began illustrating their own interpretations of Perucetus, encompassing the inspiring, the fantastical, the dramatic, and the minimalist. And all of these illustrations will likely change if the scientists ever unearth a Perucetus skull, or even some teeth. Until then, please enjoy the timeless, soothing beats underlying this Perucetus video, in which an animation of the ancient whale cruises in the shallows to do what, exactly? I guess we'll never know.