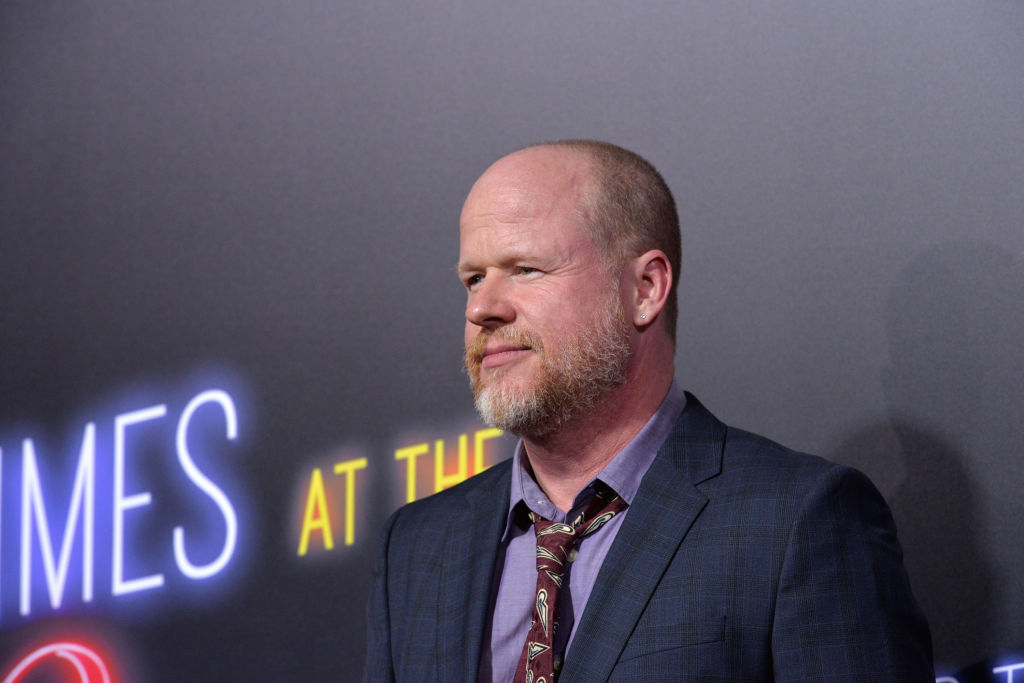

You have to admit there is a certain irony to framing someone as becoming undone, as having fallen, as being an alleged vampire, while featuring that same person’s face on the cover of a magazine, in a culture in which fame is everything and the dwindling media landscape means the chances of exercising that fame on a magazine cover—let alone one of the, like, big four—is next to impossible. "Joss Whedon, Hollywood’s feminist nerd king, struggles to explain himself," New York magazine’s latest cover reads, as the inside delivers a tale of the Buffy the Vampire Slayer creator’s fall from grace, which almost perfectly aligns with his own. "The beginning of the internet raised me up, and the modern internet pulled me down," Whedon tells author Lila Shapiro. "The perfect symmetry is not lost on me."

All of us operate according to a narrative we have adopted for ourselves. Depending on who you ask, that narrative can be closer to the truth or ... not. Usually, it’s somewhere in between. But for people like Whedon, for people like Louis C.K., even for people like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, their narratives about themselves are not only false, but foisted upon everyone else. As these men acquire more and more power, that forced autobiography becomes so ingrained that the growing pile of actions pointing to the contrary becomes easier and easier to ignore. The internet didn’t raise up Whedon; the internet raised up an idea of Whedon that he actively fostered, that his power allowed him to proliferate. And the modern internet did not pull him down, it pulled down the idea it had bought into along with everyone else. This is not about the complicity of fandom or the celebrity machine, it is about the complicity of the wider culture in the stories powerful people tell, a genre which runs on the famously patronizing adage, “Do as I say, not as I do.”

The Whedon story opens with academics deifying the sci-fi filmmaker as the founder of a new faith, having subverted centuries of oppression by creating a blonde cheerleader from the valley who kills vampires. If that sounds facetious, it’s because it’s supposed to—academics, of all people, should know better than anyone that the origin story of subverted stereotypes is usually found in the very marginalized communities that have experienced the repercussions of those stereotypes. This happens long before the inevitable white male nerd comes along and—with the help of multiple people, including the woman who discovered him—casts himself as the male embodiment of female empowerment, the savior of women in a world full of men like him. When it came to Buffy, Whedon, in the words of Shapiro, "wanted to be her, and he wanted to fuck her." And the public—from academics to fans to the media to Hollywood—in turn wanted to be him and to (in some cases, at least) fuck him. Because separating the art from the artist is only really a conversation when an artist’s bad behavior is exposed, Whedon was, for a long time, a feminist superhero because that is what he created. He then spent the rest of his career reaffirming this narrative as he acted out its polar opposite. Until, of course, the cracks in his contradiction got too big for him to paper over.

Still, Whedon knows to tweak the narrative when it isn’t serving him anymore. While he previously implied his mother helped shape him into a feminist, he now says it was difficult to grow up with her. In other words, if the feminist mother cannot serve the hero, the feminist mother will be his enemy. This is perhaps less bizarre than Cosby’s tactic—in prison for sexual assault, he said, "My political beliefs, my actions of trying to humanize all races, genders and religions landed me in this place ..."—but both approaches involve adopting a storyline which keeps these men from owning their actions. And anything is better than the real story—the boy who feels undesired grows up in a stew of resentment to be the powerful man who feels entitled to what he was denied for so long—the story a vaunted fabulist like Whedon no doubt recognizes as eminently banal.

"I know certain religions forbid idol worship," Jerry Seinfeld blurbed for the release of Cosby’s 2014 biography. "If anyone ever told me I had to stop idolizing Bill Cosby, I would say, 'Sorry, but I’m out of this religion.'" While Seinfeld’s rep has since asked that this quote be removed from circulation, it made me think of the response to Weinstein in his heyday (allegations against Cosby date back to the '60s), when everyone knew he was awful but because the industry had rewarded him so incessantly, that awfulness became a prerequisite for his grand success. Weinstein himself had recast his abusiveness as a virtue. "Let me translate brutality in the movie industry: honesty," he said in The New Yorker in 2002. "They say it’s brutal. Yeah, it’s brutal to tell the truth in an industry where everyone lies."

Everyone knows that Hollywood is built on fantasy, so Hollywood (and everyone else) bought into the idea that Weinstein’s behavior was the antidote (while it distracted from a litany of even worse acts behind closed doors). Stars like Madonna praised him at the Academy Awards as "the punisher," the big joke being that Weinstein’s name came up more in Oscar speeches than God’s—sometimes the two were even one and the same. So, while that comic book artist in the Whedon piece fell into the old cliché that fandom has a "bad habit" of deifying, the reality is that the culture at large has a bad habit of conceding to powerful people who present themselves as deities.

Though Whedon doesn’t seem to have been as destructive as Weinstein, he reportedly had a knack for demeaning women. He belittled their work, insulted their weight, threatened their careers, and generally just seemed to be an unprofessional asshole. In New York, he explained each one of these allegations away by basically claiming they did not fit the Whedon narrative—he would never upset anyone, because it would be “a problem for me”; he did not grab a coworker, because he was “never physical with people"; he did not make out with an actress on someone else’s office floor (don’t ask), because he was terrified his affairs would be found out. He did not, however, question the accuracy of descriptions of a monthly gathering at his home, which sounded like the Hollywood version of Sunday worship, in which he had his cast and crew over for some Shakespeare and some good old-fashioned poster signing (he signed, they genuflected). In Hollywood, there often seems to be an overwhelming response to men not being dicks, and an underwhelming response to their abuse of power. The acrobatics required to explain Whedon’s unprofessional behavior—apparently, he speaks in a flowery tongue?—are only used for men like him. Powerful people who act professionally tend to not require decryption.

Whedon is a misogynist who sold himself as a feminist, and the industry bought it. And then that image was sold on. Now, despite not copping to much of the behavior he is accused of, Whedon claims he has a condition (complex PTSD, the same condition, New York notes, that his ex has) that explains all of it. This is a man casting about for absolution without acknowledging the reason it is necessary. People may not be buying Whedon’s line anymore, but the media is still willing to put him on a cover, and that says something. After C.K.’s comeback in 2018 following allegations of sexual misconduct, Amanda Hess wrote at The New York Times, “When our greatest commodity is attention, one way to conceive of societal payment is for an abuser to simply refrain from calling attention to himself; to give us the time to not think of him at all.” But Whedon knows he still has the power to draw a crowd. Too savvy to lean on silence, he speaks over his actions and says, “I’m terrified of every word that comes out of my mouth,” knowing full well that his audience will still be hanging on to every single one.