On the night of Dec. 22, 2020, scientists aboard a research cruise in waters off Japan gambled on diving into an unusually warm deep-sea hole. In 2000, the Kurose Hole—technically a caldera, or crater formed in the wake of a volcanic eruption—had teemed with jellyfish and other gelatinous zooplankton. But no one had peeked inside the hole for 20 years. "It's right slap-bang in the middle of the Kuroshio current, which is us-ally three knots or more," said Dhugal Lindsay, a marine biologist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, or JAMSTEC, in Kanagawa.

Lindsay, who observed the jellies inside the Kurose Hole in 2000, always wanted to return. But whenever he managed to get a ship over the caldera, the currents were too strong to safely drop a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV. On the last day of this particular cruise, the researchers could either do a full dive where the ship was already anchored or venture out for a chance at the Kurose Hole. "We kind of went, well, it's a bit of a gamble. But probably it's worth it," Lindsay said. "And thank goodness it was."

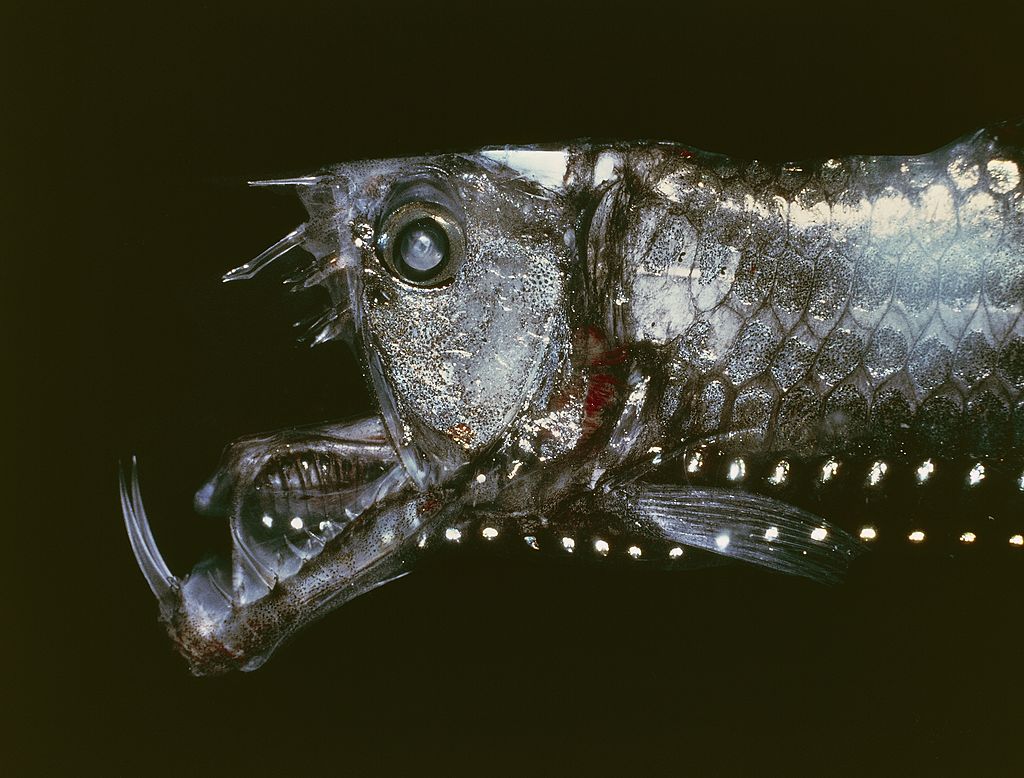

The researchers watched from the control room of the ship as the ROV sank below the sun-lit blues of the ocean and into the depths of the hole. One viperfish—a luminous predatory fish shaped like a broadsword—hovered into the feed, followed by several more. Once the ROV dropped deep enough, there were viperfishes everywhere—thousands of them inside the caldera. "Holy mackerel. Where are all the jellyfish?" Lindsay asked himself.

Sometime in the past 20 years, viperfishes took over the Kurose Hole, Lindsay and colleagues report in Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. The hole is now home to the highest density of viperfishes recorded on Earth.

"I would venture to say no one has ever seen anything like this," Tracey Sutton, the director of the DEEPEND research consortium and researcher at Nova Southeastern University, wrote in an email. Sutton, who was not involved in the research, has seen dense shoals of lanternfishes and hatchetfishes on submersible dives, but has never seen such an abundance of dragonfishes (the family of deep-sea fishes that includes viperfishes). "Such large patches of life are surely more prevalent than we know, we just have not had enough observation in the deep," he said.

Leah Bergman, a doctoral student at Kitasato University in Japan, was supposed to be on the cruise but wound up stuck in COVID-19 quarantine due to a delayed flight. When she first saw the viperfish video on Christmas, after the ship docked, she wondered if there had been a mistake with the identification.

But they were clearly viperfishes, predominantly the Sloane's viperfish Chauliodus sloani. And they appeared to be eating each other. "I was almost as shocked to see two viperfish attacking one another as I was when I first realized that there were thousands in the caldera," Bergman said. The ROV captured some serendipitous footage of a failed act of cannibalism, in which one viperfish bit the head of another twice before swimming away. Opportunistic cannibalism is uncommon among viperfishes, which are sit-and-wait predators. "If all they do is sit around and wait, then two viperfish meeting one another is a very rare event," Bergman said. But the viperfishes inside the Kurose Hole had clearly resorted to it due to their circumstances (living inside the cramped quarters of a hole).

Why were there so many viperfish there in the first place, and why couldn't they leave? The researchers speculate the fish may have wound up inside the hole as larvae—perhaps the result of a pair of mating viperfish spawning within the hole, or a patch of fertilized eggs drifting into its depths. In Japan, viperfish larvae mature into juveniles inside the thermocline, or the area in the water column where temperature rapidly declines. The thermocline inside the Kurose Hole lies beneath the opening of the caldera, meaning "there would be no way of escaping the Kurose Hole after the larval viperfish sank and matured," Bergman said.

"This is an excellent theory," Sutton said. "Otherwise, would one have to assume that viperfishes outside the caldera are aware of conditions inside and then actively swim into it." However the viperfishes got there, Lindsay suspects they have been reproducing inside the hole, as the ROV captured footage of adults and juveniles.

The bottom of Kurose Hole was once once a hub of hydrothermal activity, where chemicals gushed out of vents on the seafloor. Although the other calderas nearby remain hydrothermally active, geological surveys have shown the vents at the Kurose Hole have not been active for over 40 years. But strangely enough, the 2020 dive found the water inside the Kurose Hole warmed by 12 degrees Fahrenheit. The warm water might result from hydrothermal activity occurring beneath the base of the hole, but the researchers cannot say for certain without a survey. "We couldn't find an active vent anywhere, so it's probably geothermal energy," Lindsay said. "It might be becoming active again, who knows."

The curious hotness of the caldera offers scientists valuable insight into how deep-sea communities may shift as the world's oceans warm under climate change. "The deep sea has been so stable and slow-changing over the millennia, there is theoretically no reason for them to be very adaptable," Sutton said. But the ROV glimpsed two species known to prefer colder waters— the Kaup's arrowtooth eel and a red fish called the alfonsino—suggesting these species may be more resilient to warming waters than previously thought.

If the fish found in the Kurose Hole continue to reproduce inside the hole, the species could undergo microevolution, which could increase their adaptation to warm water and, consequently, their resilience to climate change. "This could be like a factory for producing deep-sea species that are going to survive as things warm up," Lindsay said. But even if these potential "winners" of climate change can adapt to new temperatures, Sutton warns, that alone does not guarantee their success. "The winners need to eat," he said. "Their prey would also have to be successful, or food will limit them."

They may also face new competition: the cameras documented species such as the Channel scabbardfish and Japanese horse mackerel living in new depths, likely due to the warmth of the water. Bergman says this phenomenon mirrors changes that are already happening with climate change in mountainous habitats, as species living lower on the mountain can expand their ranges upward and squeeze out the animals once living on the peak. "As waters become warmer in the deep ocean, shallower species may begin to dive deeper, and this could eliminate some deep-sea species," Bergman said.

Lindsay hopes to return to the Kurose Hole for more experiments. But deep-sea cruises are expensive, and much of his team's efforts will be devoted to securing baseline data for sites designated for exploratory deep-sea mining. "They're actually planning to do a mining test in the Japanese EEZ in one of the calderas in Ogasawara in the next few years," Lindsay said. Until an ROV can return to the Kurose Hole, no one knows how long the viperfishes will remain crowded into the caldera. But one thing is certain: The deep ocean is full of strange holes, and we must look inside them.