Cal "Big Dumper" Raleigh is an outlier in the obvious sense—he is the current MLB home run leader—but pile on the descriptive adjectives, and you wind up with an amalgam of three truths, all theoretically past their prime: Cal Raleigh is a switch-hitting catcher who plays for the Mariners. Somehow, he is still the current MLB home run leader by a not-insignificant margin of two, his 26 homers beating out names like Aaron Judge and Shohei Ohtani. Per traditional standards, he is slashing a very respectable .264/.370/.632. Throw in some adjusted metrics, and he has a 182 wRC+, which is to say 82 percent better than the average MLB hitter, which is to say, the second-best player in baseball, beating out names like Freddie Freeman and Shohei Ohtani. Raleigh has, so far, cared not for the underpinnings of modern baseball. Where to even start? Perhaps in iambic tetrameter.

PART I: THE CONCEPT OF BEING A GOOD CATCHER

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

Before the season began, when the bar for Cal Raleigh's offense sat at "being the best Mariners hitter," finding a star catcher required definitional wrangling. Like a center fielder, the catcher is permitted to sacrifice offense for positional value and defensive prowess that is, with a few exceptions, inscrutable if done well, and rare when visible. The conventional wisdom valuing subtlety in pitch framing has gone away in favor of dramatic, yanked-glove moments that indisputably get results, but lack appreciable aesthetic clarity. Conversely, great catcher arms make for satisfying viewing, but catchers are lucky to face 80 stolen-base attempts a season to prove their worth. Inevitably, catchers are rarely compared outside of their cohort, and within their cohort the balance shifts: A bad offensive catcher is par for the course, while a bad defensive catcher makes every pitch hell to watch.

Speaking as someone who has watched every J.T. Realmuto caught-stealing in 2019 a number of times best described as too many times, there is meaning in the defensive minutiae. But here we are forced to draw a line between "cool player" and "star player." One will always remember the defensive guys who built long careers off less lauded accomplishments—it is arguably cooler to be an offensive black hole and still maintain a decade-long career—but it doesn't change the fact that, by the tacky concepts of "value" and "fWAR," the third-best catcher in 2024 was the San Francisco Giants' Patrick Bailey, who had a .637 OPS that year.

So, let's get some offense into this joint. The prior-to-season stars or, more accurately, noted names: Will Smith, boosted by benefit of being a Dodger and having Dodgers moments; Austin Wells, boosted by benefit of being a Yankee and being a yanker; Adley Rutschman, boosted by benefit of being young, or relatively so (he is one year younger than Raleigh); Dillon Dingler, as everyone anticipated; the Contreras brothers, if you put a gun to my head; and Big Dumper himself, though primarily for his defense. Ignore 2025 Raleigh, and none of them have put together a particularly memorable season, with a possible exception for Smith. For a catcher, Raleigh has always been a great hitter. You just wouldn't be saying any of his catcher peers' names in the same breath as Aaron Judge.

Contextualizing the abnormality of Raleigh's power hitting this season requires an acknowledgement that it is still early in the season and, to a certain extent, it shows. If Raleigh were to continue at this pace, it would easily be the best batting season a catcher has had—adjusted for park factors (see Part III) and hitting environment—since Buster Posey in 2012 and Joe Mauer in 2009. The belief that Raleigh can continue on like this requires belief that he will have, easily, the greatest season by a catcher post-2000.

But while some concessions must be made to placate the sample-size child—Nine homers in 12 games, she yells, which, by the way, is also the same number of Mariners losses in that timespan!—Raleigh's success is already impressive at face value. Will Smith's 2025 season is also nestled in that list of great modern catcher seasons, right under Posey and Mauer; unfortunately for Smith, he only has six homers. Meanwhile, Raleigh's home run count after 60-plus games nearly matches Mauer's season total of 28, has already exceeded Posey's season total of 24, and is easily on pace to shatter his previous season best of 34. This is a good point at which to note that the state of catchers with power is dire enough for Raleigh's 34 to already rank as the fourth-most by a catcher this quarter-century, beaten out only by a couple early-2000s Mike Piazza seasons, and Salvador Perez's 2021, when he hit a whopping 48.

Then again, we're not putting Raleigh in conversation with his catcher brethren. This is a man who is good enough to DH when he is not starting as a catcher. We're putting Raleigh in conversation with Aaron Judge. Cal Raleigh is currently on pace for a 63-homer season, if you truncate. I'd like to see Aaron Judge do that.

PART II: THE CONCEPT OF BEING A GOOD SWITCH HITTER

The Sun now rose upon the right:

Out of the sea came he,

Still hid in mist, and on the left

Went down into the sea.

The only thing cooler than a catcher who maintains a long career in spite of being an incompetent hitter is a switch hitter. It's a relatively short list. Of the 168 qualified hitters in MLB so far this year, just 17 are switch hitters. Unlike with catchers' offensive statistics, these switch hitters are not all scrubs. There's José Ramírez, Francisco Lindor, Elly De La Cruz, Ozzie Albies, and playoff Tommy Edman.

Borrowing from Mike Petriello's analysis of Yoán Moncada's 2021 BABIP, a switch hitter can be viewed as two separate hitters bearing naming conventions from the '30s. There was Lefty Moncada, who hit a lot of line drives. Then there was Righty Moncada, who more or less sprayed hits all over the place, making targeted defensive positioning harder. Mix them together et voilà: an obscene BABIP machine. What a fun season for the Chicago White Sox! Moncada is now on the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.

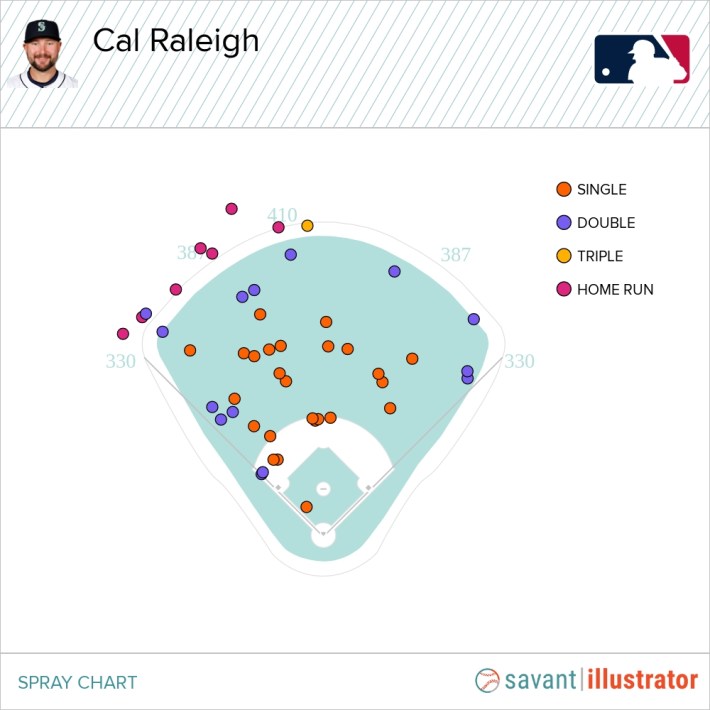

From Raleigh's brief 2021 stint until his first qualified season in 2023, there was a clear difference between Lefty Raleigh and Righty Raleigh that can be easily summarized by his spray charts from those years:

Or, kind of. It's a bit misleading, because Raleigh naturally takes fewer at-bats as a righty than a lefty, due to seeing fewer left-handed pitchers than right-handed pitchers. The left-handed MLB pitcher populace currently stands at an over-represented quarter of all MLB pitchers, and Raleigh's percentage of plate appearances as a righty fluctuates about there. He has taken a slightly higher percentage of his plate appearances as a righty since 2024, hovering about 28 percent this season, but the percentage dipped as low as 19 percent in 2023.

Still, like most switch-hitters, one version of Raleigh was clearly superior to the other. In this case, Lefty Raleigh was lapping Righty Raleigh. Even in 2024, when his spray charts started looking more symmetrical as he developed more power, Righty Raleigh was about a plumb average hitter while Lefty Raleigh boasted a 125 wRC+. You know what they say about right-handed people; Raleigh's Mr. Hyde was dragging him down.

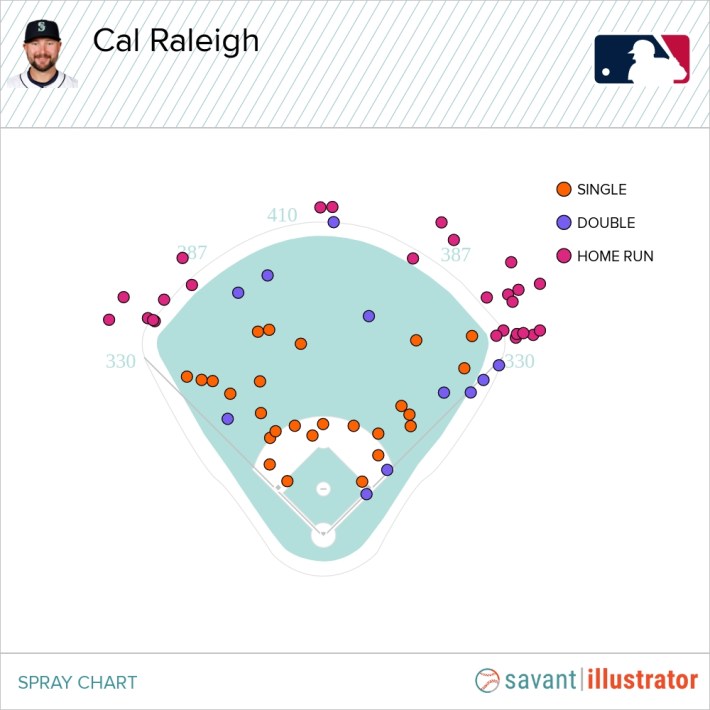

That has not been the case this year. In 2025, Lefty Raleigh and Righty Raleigh boast similar offensive production and swing dimensions. It's almost as though they're the same person. Lefty Raleigh has a .999 OPS and a 180 wRC+. Righty Raleigh has a 1.004 OPS and a 186 wRC+.

Go back a day, and the adjusted numbers are even closer. It was Lefty Raleigh who went 1-for-5 last night against the Arizona Diamondbacks; prior to that, he had a 1.017 OPS and a 185 wRC+. It's only in the sausage-making inspection that you start to see differences. Righty Raleigh still has the same peripheral metrics that hint at a worse hitter when compared to Lefty Raleigh—a much lower walk percentage (five percent vs. 17 percent), a higher strikeout percentage (35 percent vs. 23 percent), a higher percentage of ground balls (31 percent vs. 21 percent)—but has made up for that so far by hitting the ball harder and pulling the ball more, which is where Cal Raleigh as an overall entity gets his power. No need for opposite-field home runs if you can simply switch sides and pull the ball there instead; no need for BABIP luck if you can hit it out of the park.

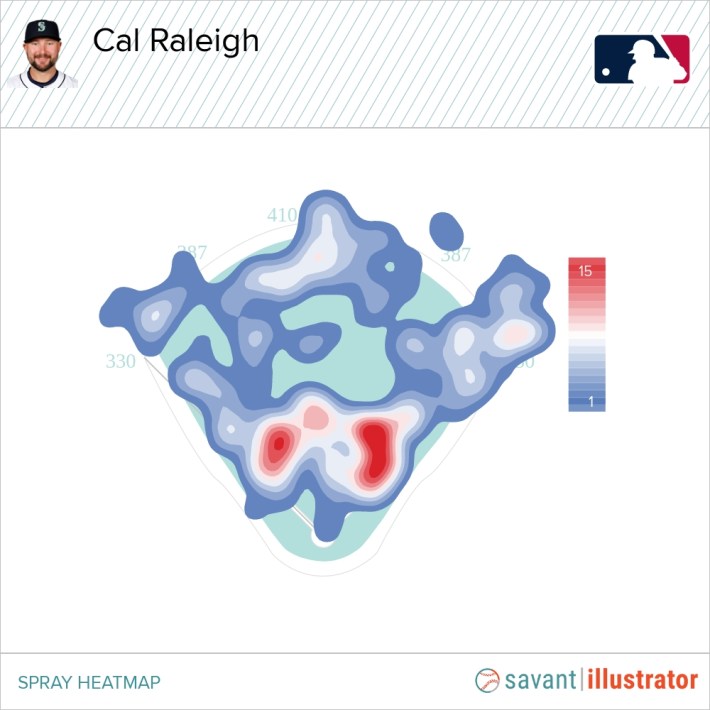

The end result is a pleasing symmetry in spite of the plate-appearance discrepancy. The true measure of any great hitter is whether or not their batted ball heat map can be used as a Rorschach test.

Fun fact: In 2024, Cal Raleigh took one at-bat as a right-handed hitter against a right-handed pitcher. This took place on Sept. 25, against the Houston Astros' Héctor Neris. He struck out swinging in three pitches. It remains to be seen if he will ever try this again.

As far as I am aware, Aaron Judge has never taken a single plate appearance as a left-handed hitter.

PART III: THE CONCEPT OF BEING A GOOD MARINERS HITTER

There passed a weary time. Each throat

Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time! a weary time!

How glazed each weary eye—

In the context of where Raleigh plays, his raw stats are even more impressive than his adjusted ones. This is not poking fun at the Seattle Mariners for doing the pitcher version of the Baltimore Orioles, but noting that the Mariners' home park effectively is for pitchers what Coors Field is for hitters. Hitting stats are deflated there pretty much across the board, except for strikeouts, which are inflated to hell and back. Pretty much any hitter coming into the team will see an increase in K percentage, through no fault of their own. Some possible factors: weird batter's eye, basic weather concepts like the sun and wind.

Raleigh has been performing slightly better by OPS when not batting at home, though the discrepancy isn't as bad as one might expect: Even in the Mariners' pitcher-friendly home he has a .980 OPS, compared to his 1.022 on the road. Considering that no other Mariners hitter has above an .800 OPS overall, home Cal Raleigh would still be far and away the Mariners' best bat.

What is amusing if not particularly conclusive about Raleigh's home/away splits this year is how Lefty Raleigh and Righty Raleigh differ. Lefty Raleigh much prefers playing away from home. Again, Cal Raleigh's 2025 season is such that his poorer splits are still well above average (i.e., OPS hovering about .900), but Lefty Raleigh's away OPS is 1.079. Meanwhile, Righty Raleigh much prefers playing at home, with a home OPS of 1.127. (Does this perhaps reflect right-handed hitters generally faring better in Seattle than left-handed hitters? An over-simplified search yields early results of eh, not really.)

Raleigh's big homers were a hallmark of last year's stagnant offense, and now he's hitting way more of them. He has been swinging the bat a tick faster, walking a bit more, striking out a bit less, and hitting the ball in the air more by a not insignificant amount. But the most dramatic change that one might attribute to his unprecedented offensive production has been, as previously mentioned, how much he is pulling the ball, especially on balls in the air—especially important as pulled fly balls have generally proven to be most productive batted-ball profile out there.

FanGraphs and Statcast have differing listed statistics for pull percentage (seeing as Statcast's cumulative pull, straight, and oppo percentages displayed on player profile pages don't add up to 100 percent, I assume the thresholds are tighter), but both see Raleigh with a 10-percent additive increase from last year. It's been enough to give him a ludicrous home-run–to–fly-ball ratio of 28.3 percent (per FanGraphs), a statistic in which Raleigh has always over-performed, but never to this extent. Rephrased, that means that over a quarter of fly balls off Raleigh's bat are going to be a home run. The MLB average home-run–to–fly-ball ratio is approximately 10 percent. Is this sustainable? Don't worry about it.

I will never talk down about Julio Rodríguez, may he eventually find the consistency he had in his rookie season, but it feels apt for the Mariners to receive help, once again, from an unanticipated corner. From Jarred Kelenic to Julio Rodríguez, and now Julio Rodríguez to Cal Raleigh. As it happened, so it will happen again.

PART IV: I WOULD NOT NECESSARILY SAY THAT I BELIEVE IN THE SEATTLE MARINERS' ABILITY TO MAKE THE POSTSEASON, BUT IT IS AT LEAST NICE TO HAVE A HITTER TO REALLY ROOT FOR, AND FOR THAT I THANK CAL RALEIGH, NO MATTER HOW SUSTAINABLE THIS MAY OR MAY NOT BE

I fear thee, ancient Mariner!

I fear thy skinny hand!

And thou art long, and lank, and brown,

As is the ribbed sea-sand.

Despite at one point being eight games above .500 in late May and comfortably leading the AL West, the Mariners' recent losing skid has set them back to a 33-33 record, three games back from the Houston Astros. Last night, they lost 10–3 to the Arizona Diamondbacks. As of June 11, they have a precisely 50 percent chance of making the playoffs. But do not forget: Cal Raleigh is currently on pace for 63 home runs this season.