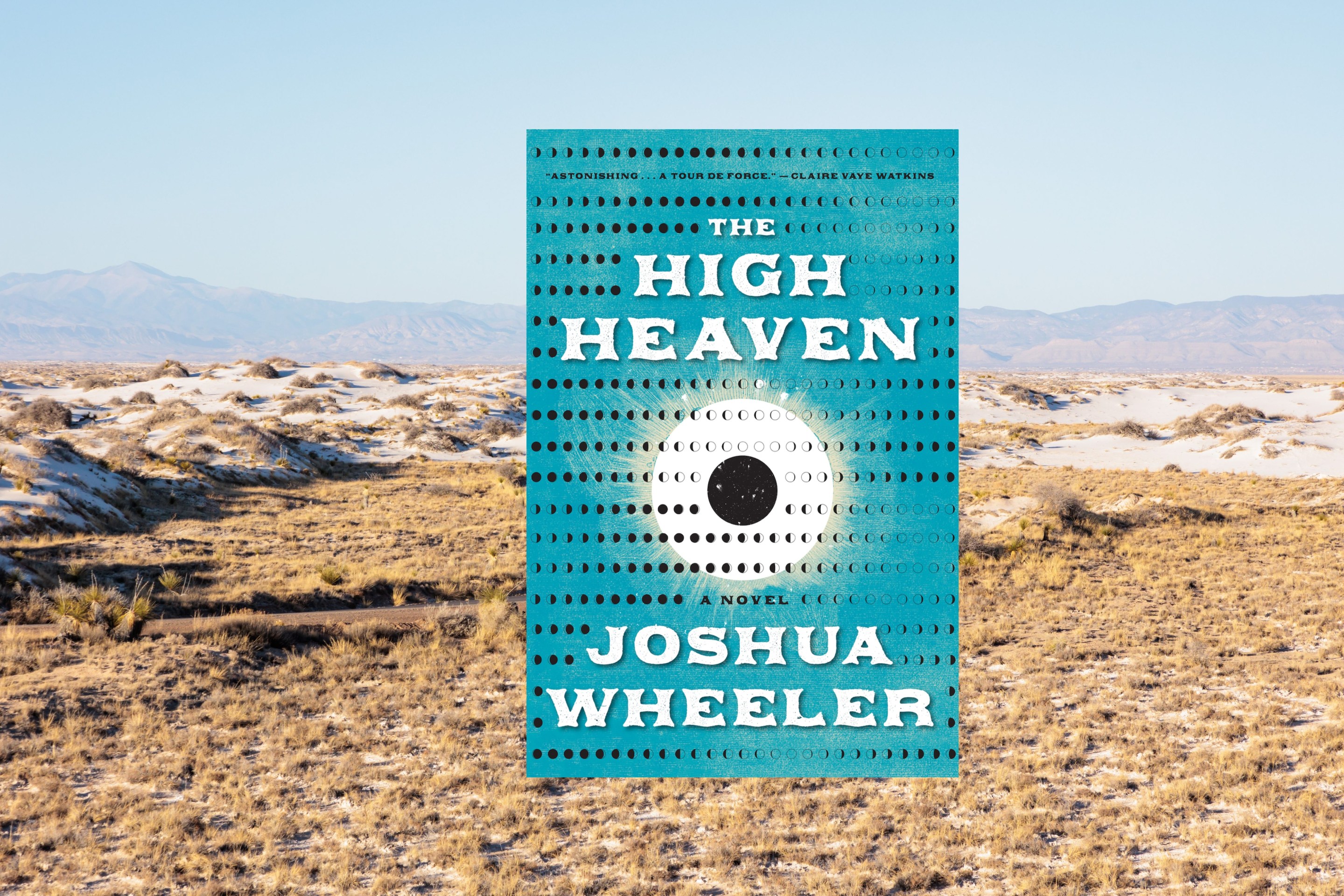

We first meet Izzy Gently, the protagonist of Joshua Wheeler’s captivating debut novel, The High Heaven, as a child. She is alone, wounded, and wandering. The year is 1967, and disaster has befallen the doomsday cult in which she’s grown up after the local Sheriff’s office raided their compound, discovering a dead body and a landing strip with a sign welcoming extraterrestrial visitors. Rumors had long circulated among residents of Alamogordo, New Mexico, about what was going on at the farm in nearby La Luz, but nothing like this had ever happened.

The first person Izzy comes across is Oliver Gently, a local rancher who, along with his wife, Maude, treats her wound and takes her in. Wheeler himself is an Alamogordo native back seven generations, which he writes about at length in his 2018 essay collection, Acid West. Even as Wheeler makes pains through an author’s note to establish the fictitious nature of the characters and locations featured in the novel, his love and care for the place, and his feelings about what has been done to it, shine through in the quality of his attention to it.

Oliver finds Izzy the day after the great failure of the first Apollo mission, which ended in the deaths of all three crew members after a fire broke out during a test; the mission never made it off the ground. The disaster of Apollo 1 holds particular resonance for Oliver: His family ranch is near the White Sands Missile Range and is increasingly being encroached on by government testing sites, as it has been for years. Oliver knows intimately the costs associated with the manic march forward of Cold War America, knows what it’s like to fall victim to the ambitions of a distant government to whom individual lives hold little weight on the scales of progress.

“All that worry over Soviet bombs,” says Oliver to an Army representative who comes to negotiate for his land, “and the only people ever dropped anything on my family is yall.” It’s an echo of a passage from Joseph Maslow’s The Nuclear Borderlands, which Wheeler discusses at length in his essay on the fallout from the Trinity test, “Children of the Gadget”, included in Acid West: “The United States…is the most nuclear-bombed country in the world, having detonated nearly one thousand nuclear devices within its own territorial boundaries.” Many of these bombs were detonated in the part of New Mexico where the Gently ranch is located. Oliver has had enough.

Izzy comes of age on the Gently ranch under the (not officially authorized) care of Oliver and Maude, whose only son is stuck in Vietnam. With his son gone and his family ranch firmly in the government’s crosshairs, Oliver views caring for Izzy less as charity than as an act of moral fortitude. “He was done getting pushed around and keeping quiet about whatever fell to his ranch, or exploded on his ranch, or got took from his ranch. He settled it in his mind then. Can’t let nothin ruin the child no more. Whatever she is, she’s our line in the sand.” Oliver and Maude shelter Izzy and ease her into their world, one filled with loss, with government encroachment and neglect for their well-being, and yet nonetheless filled with real tenderness. That tenderness is one of the throughlines of The High Heaven, which goes on to trace the roving life Izzy lives across the American southwest, eventually landing and settling in New Orleans as a social worker.

Before that, we follow Izzy as she waits tables for roughnecks, assists an eccentric geologist on the hunt for space rocks, finds “a way to scam people into helping themselves” in West Texas, works as a light operator at SeaWorld in San Antonio, cultivates a hidden weed farm in a national forest in East Texas, and generally tries to outrun her past. There’s a Charles Portis-like quality to this part of the novel, which covers much of Izzy’s middle age and is populated by wild characters with cockeyed dreams whose lives don’t register in the stories America tells about itself. Izzy lives her life among these unseen, among those for whom America’s relative global position means little. “I look around and it’s just the conquered,” says Rocky, the rogue social worker who sets Izzy up on the weed farm.

And yet, Izzy retains her sense of cosmic wonder, leftover from her childhood among people waiting for rescue from beyond the stars, even as she lives a difficult life made no easier by her government’s fixation on space exploration and technological progress. NASA’s moonshots, the cycles of the moon, the power of an eclipse—everything about the moon inspires awe in Izzy, and humanity’s quest to reach the moon mirrors her own lifelong quest for healing, for escape, for elsewhere.

In a novel of cosmic proportions like Wheeler’s, it is striking just how carefully and beautifully the book attends to the out-of-the-way places that feature in it. It’s a small miracle that Wheeler manages to do that so effectively in a novel so concerned with matters of exploration and escape, both earthly and beyond. The reader might expect it of his treatment of Southern New Mexico, about which he has written at length in his past work, but he devotes the same care to the way he writes about various locales across Texas, and the New Orleans of the destitute—each place is vibrant and alive, written with an attention to its particularity that lends weight to the novel’s visions of escape.

Part of Wheeler’s manner of attending to place revolves around the book’s structure: The High Heaven is separated into three parts, Wheeler adopting a form in each to match its locale—the neo-Western for the book’s first part, the picaresque for its second, and the Southern gothic for its third. The movement between genres is a tribute of sorts to the literary traditions of each, and introduces a layer of formal complexity and play to the novel without sacrificing any of the narrative consistency of Izzy’s story.

Izzy lives a hard and often lonely life, but she’s consistently buoyed by the people around her, most of whom come into her life by dint of tragedy or sheer abject necessity, or, in the case of the Gentlys, some combination of both. The world of The High Heaven is a deeply solidaristic one. One of the book’s defining passages gets at this idea: the beauty that comes out of our shared struggle.

This must be the flow of things, all of life one great big pain exchange. You take some and you pass it on. You don’t worry none about running low because there will be more to come, more to pass along. You look at it one way and it’s a bleak cycle sure to bring you down just to think about. You look at it the other way and it’s a triumph, how we live to share the burden…On the big scale, the pain exchange was awful and endless. On the small scale, the pain exchange was love.

If companionship along the pain exchange we all share is the foundation of The High Heaven, the moon is its illuminating light. Toward the end of the novel, as NASA is working toward returning to the moon through its Artemis missions, Izzy is working as a social worker in New Orleans with a quest to help those who have lost the ability to see the moon. This moonlessness acts as a stand-in for a sort of existential absence, an absence of wonder—“If we cannot be astonished by what is there, then we must learn to be astonished by what is missing.” The quest she devotes herself to in the novel’s final section is a quest to reanimate the downtrodden in her orbit, to re-enchant their lives.

For Izzy, the moon is “like a protective lens for eyeballing unfathomable power without totally giggling your brain. Here I am, your path to fathom the unfathomable, says the moon.” The unfathomable is, of course, both cosmic and deeply human. The High Heaven watches from afar (mostly from television screens) as humankind meets disaster in its efforts to reach the moon, and then reaches it, Izzy chief among the watchers. But perhaps more than the cosmic, The High Heaven is concerned with that which is unfathomably human, and the moon acts as a portal to understanding, or at least to easing incomprehensible pain, just a bit. Oliver tells this to Izzy early on, in another passage that reverberates throughout the novel:

Can I tell you somethin my mother taught me? said Oliver. I was in the war, you know? A couple wars ago anyway. When I left, Momma said, Anytime things get bad, just look up at that moon. I thought she might tell me something sappy like, I’ll be lookin at the same moon too…But she said, Just pretend that’s you. That moon. Kinda silly but it sure helped sometimes. When stuff got bad, I looked up there and it was, like, if I was the moon, I was further off from things. Could see better. Be less scared.

This lesson stays with Izzy through the rest of her life, and her fascination with the moonshots both mirrors it and confounds it. Once we make it to the moon, if it’s no longer an unreachably distant force, can it still hold our pain? Who do we become when we lose our sense of the cosmic?

The day the Apollo 11 mission reaches the moon, Izzy is taken aback by the reaction. “The day hadn’t cooled one bit but everyone ran into the cotton fields yelling skyward, We are the moonpeople! At last, the moonpeople are us! The excitement startled Izzy. She floated back to La Luz and her family there beckoning rapture atop the mountain.” For Izzy, reaching the moon takes her back to her childhood, expecting transcendence and salvific escape. Finally reaching the moon creates in humankind something akin to the madness Izzy was victim to as a young girl, tasked with using salt and clay to preserve her mother’s dead body while the cult Izzy was born into awaited her mother’s resurrection.

We are, after all, not the moonpeople. If there’s one message Wheeler’s novel brings into sharp focus, it’s this: We belong here, with and for each other.