In the winter of 1977, Sports Illustrated reporter Ray Kennedy ventured into the Riverside Table Tennis club at 96th and Broadway. It was a dingy joint with leaky pipes, below street level, beneath a supermarket, inhabited by characters with names like Freddie the Fence, Betty the Monkey Lady, and Tony the Arm, a smattering of celebrities—Walter Matthau! Art Carney! Bobby Fischer! Kurt Vonnegut!—and a group of violinists from the Metropolitan Opera.

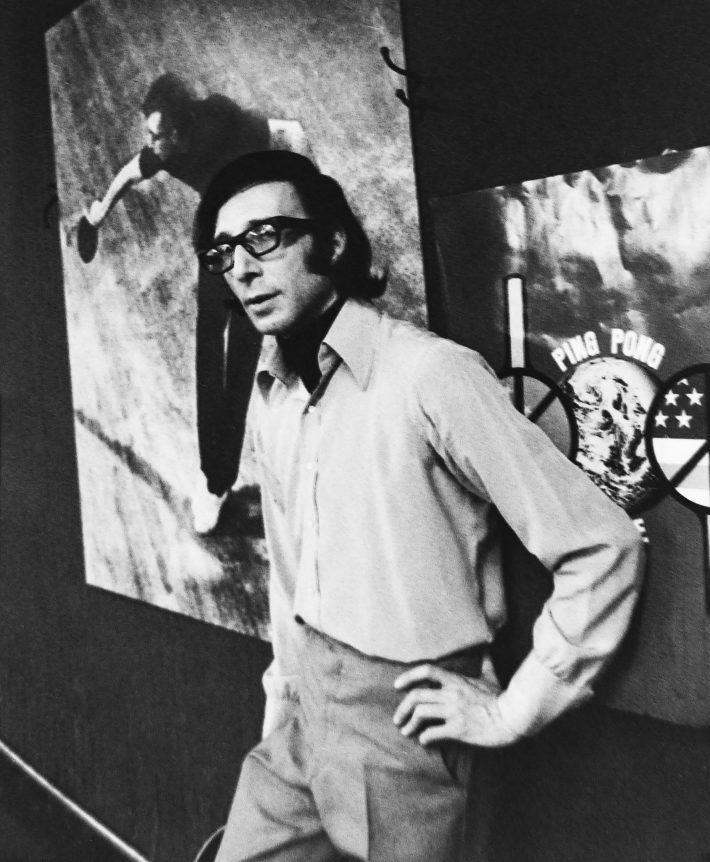

The club’s main draw was the magniloquent Marty Reisman, its owner-operator, with a heavy emphasis on "operator." Marty was then 47 years old, past his prime as a competitive athlete, which had been back when the United States was a ping-pong powerhouse and New York City was the hub of the sport in this country. But "The Needle," so-called for his cadaverous frame as much as his sharpness, was back in the spotlight, because table tennis was enjoying a minute in the aftermath of the Ping-Pong Diplomacy affair with China.

Reisman had taken advantage of the moment to publish his ribald and mostly true memoir, a romp of a read with the immodest title of The Money Player: The Confessions of America's Greatest Table Tennis Champion and Hustler, in which he related said hustles. To lure in prey for the wagers, he'd agree to play with any imaginable handicap—using a Coke bottle for a paddle, or a garbage-can lid, a shoe, a light bulb, his eyeglasses. Think Minnesota Fats meets Bobby Riggs meets Stu Ungar meets Jimmy the Greek.

Kennedy watched as Reisman, roguishly outfitted in black riding boots and a silk shirt with billowing sleeves, picked up his antique Hock Special hardbat paddle and dispatched a frisky opponent after spotting the young man an 18-point handicap (in a race to 21), the twick-tock, twick-tock, twickety-tock of ball-meeting-paddle-meeting-table providing the resonant soundtrack. Marty pocketed the cash, sold the rube a copy of his book, and offhandedly mentioned that a Hollywood producer had optioned the film rights to Money Player. He suggested that Bob De Niro, fresh off starring in Taxi Driver, "could do it right."

Some 51 years after the publication of Money Player, Hollywood is finally getting around to portraying Marty on the big screen—and, no, De Niro is not involved. Marty Supreme, directed by Josh Safdie and starring Timothée Chalamet as "Marty Mauser," in a wispy mustache, pleated trousers and vintage spectacles, promises to offer a "loosely inspired by" portrait of the most charismatic table-tennis player the world has ever witnessed.

Reisman died in 2012 at age 82, so he won't be around to walk the red carpet. Though you never know with Marty, whom Booker Award–winning author Howard Jacobson once dubbed "the fatal Odysseus you have to follow beyond the sunset." Given his wheeling-dealing, he probably negotiated a rider allowing him to attend the premiere after his death.

For most of us, table tennis functions as a diversion. You play under buzzing fluorescent lights on a fold-up table in a neighbor's garage. Your kids play it at summer camp, the tournament bracket hand-lettered on colored construction paper. It's quite possible you've played more games of beer pong in your life.

The colloquially named ping pong—a trademarked designation once owned by the game company Parker Brothers—is likely the only onomatopoetic sport.

No matter what you call it, it's serious competition. Table tennis has been an Olympic sport since 1988. The fact that no American athlete has ever medaled in it at the Olympics, or that Lily Zhang's mixed doubles bronze at the 2021 World Table Tennis championships was the first American medal at the biennial tourney in 62 years, doesn't diminish its athleticism or its worldwide appeal.

The U.S. was once a powerhouse. Marty Reisman's brash hustler persona eventually came to overshadow his elite talent, but as he recounted to the legion of writers—from Murray Kempton to Jerome Charyn to Susan Brownmiller to George Plimpton—who came to schmooze and volley with him, once upon a time, in the late 1940s and 1950s, a slew of skilled Americans, Marty very much included, were ranked among the world’s best pongistes.

These athletes changed the direction of the sport. Their matches were contests of stamina with extended, flurried rallies as they roamed far beyond the table to retrieve their opponent's shots, then reversed course and raced to the net to cover a drop shot. Thousands of adoring, chain-smoking spectators followed the action with the rapt attention these days reserved for tennis.

"To play with the hard rubber racket is to be in communion with the ball," Marty put it. "The strategy, the entrapments, the players could be understood and enjoyed by everyone."

Reisman grew up Jewish and poor in New York City. Comedian Jackie Mason was a childhood friend. Reisman's father owned a fleet of taxis that he squandered shooting craps and playing poker; Marty admired his dad and also called him a "compulsive loser." Young Marty overcame a nervous breakdown at age nine—he was admitted to Bellevue for a month—and poor eyesight by shaking hands with a paddle. It was as if he'd gripped a lifeline: Ping pong was basically the only job he ever had.

He learned the rudiments of the game in Seward Park and at a settlement house. He was obviously gifted from the get-go, but didn't excel until he dropped out of high school and matriculated at a fabled ping-pong emporium in Midtown Manhattan. Lawrence's was located on two floors in a former speakeasy allegedly once owned by "Legs" Diamond, the bullet holes in the walls a relic from Prohibition. A Barbados-born black man named Herwald Lawrence turned the establishment into the focal point for the sport in the U.S. and policed the Friday night tourneys (and wagering: one unofficial rule at Lawrence's was that no one played just for fun) that lasted until dawn. "Care for a game, old top?" was his greeting, delivered in a clipped British accent, whenever a newbie wandered into his establishment at 1721 Broadway.

Amid the ceaseless twickety-tock, a teenaged Reisman learned from ping-pong royalty, many of them fellow Jews or émigrés from Hungary and Czechoslovakia, names now familiar only to the cognoscenti: Sol Schiff, the redheaded southpaw who led the U.S. to its lone Swaythling Cup at the 1937 Worlds; Lou Pagliaro, nicknamed "The Terrible Midget" during his three-peat streak as U.S. men's singles champ; and Dick Miles, the 10-time U.S. men's singles champ who was "Bjorn Borg to Reisman's Jimmy Connors," according to journalist Nancy Franklin.

Dick was a product of the Upper West Side; Marty, the Lower East Side. The 5-foot-7, 125-pound Miles was compact and aloof; the 6-foot, 135-pound Reisman was a gangly whiz-bang. Miles walked around with a well-worn copy of Ulysses under his arm and wrote erudite articles for Sports Illustrated; Reisman's memoir, as Jacobson noted, was ghostwritten.

They shared a maniacal obsession. "I have a machine, a girl friend and a dog," Miles once told The New York Times. "Those, and the game, are all I need." It should be noted that the machine was a Stiga that fired ping pong balls at him at every angle, spin, and speed so that he could practice at home.

"His forehand drive was an amazing work of art that could demolish any defense," Reisman wrote after Miles died in 2010. "In his prime, I saw him make Richard Bergmann, a four-time World Champion, break down and cry in the locker room after the beating Miles gave him in 1949 before 10,000 spectators in London's Wembley Stadium."

When the two met, what Reisman described as "withering combat" ensued. Across nine feet of the green wooden expanse on Lawrence’s renowned table No. 7, he and Miles "risk[ed] our last buck against each [other] with our egos on the line." The nightly sparring and double-or-nothing bets helped Marty whittle his 10-point handicap down to zero as he developed an "atomic blast" forehand that surpassed even Miles's.

The two met in the finals of the U.S. championships in 1948 and '49, with Miles triumphing both times. In 1951, Reisman took the first two games before Miles steadied and won the next two. Reisman was up 17-9 in the decisive fifth game when, according to one account, the telephone started ringing. Quipped Marty: "If that's the Associated Press, tell them I haven't won yet."

Miles rallied to take the match and his sixth U.S. title.

Crucially, their rivalry flourished during the classic "hardbat" era, when everyone used the standard hardwood paddles covered with a thin layer of pimpled rubber. Marathon rallies were the norm. Miles once detailed the infamous (and apocryphal) "long point" at the 1936 Worlds in Prague: The very first point of the match lasted two hours and 12 minutes, they say, with the ball crossing the net approximately 12,000 times. The umpire had to be replaced after his neck locked up.

Even if exaggerated, the exhausting spectacle led to reform. Games were limited to 20-minute duration, and the net was lowered. This served to invigorate the sport, highlighted by the aggressive, back-and-forth exchanges that suited the Americans' style. After the war, when international sports contests resumed, Miles and Reisman were favored to become the first American men to win the singles title at the world championships. (Ruth Aarons won the women's title twice in the 1930s and remains the sole American to win a world singles title.)

Miles and Reisman led the U.S. to the bronze in team play at the 1948 and '49 world championships, and Miles and Thelma Thall took the gold in mixed doubles in 1948. That same year, Miles held a 2-1 game lead and then a 16-9 edge in the deciding fifth game in the singles quarterfinals against Czech great Bohumil Vana. But Miles couldn't capitalize on his advantage. "I blew it," he later said, calling it the "cruelest loss I had ever suffered."

The following year, as 19-year-old Marty became "more serious, more scientific" about his game, he advanced to the singles semis, dropping just one game in six matches. He was so convinced of glory that he "envisioned ticker-tape parades through the streets of New York and had already composed in my mind the cable I would send my dad." He was, he later admitted, "too confident," and fell to the seasoned Vana in three straight games.

Marty redeemed himself later that month in the British Open at Wembley Stadium. He stayed sharp, winning money matches in the backrooms, then proceeded to defeat Miles in the semis, and Hungarian legend Victor Barna, considered table tennis's Babe Ruth, in the finals to take the prestigious title, something no American man has ever done.

In 1952, Reisman’s game "had never been sharper" when he flew to India for the world championships at Bombay's Brabourne Stadium. What ensued so demoralized him that he never fully recovered, and completely revolutionized the sport.

Japan was making its first appearance at an international sports event since before the war. Its team included an unknown competitor named Hiroji Satoh, whom Reisman described as "a picture of Oriental humility. He wore horn-rimmed glasses. He was pigeon-toed, slight in build, a wisp of a man."

Satoh secreted his paddle in a wooden box. Turns out, he had covered one side of the bat with a three-quarter-inch covering of smooth foam rubber; he used that side whenever he struck the ball, forehand or backhand. The padding produced "eerie flights" of the ball, according to Reisman, that was "like nothing any of us had seen before." Sometimes, the ball "floated like a knuckleball, a dead ball with no spin whatsoever. On other occasions the spin was overpowering."

Marty and every other top-ranked player had instinctively learned to anticipate the flight of the ball—its spin, velocity, and trajectory—in part by the sound it made coming off the paddle. Twick-tock, twick-tock, twickety-tock. But Satoh's foam muted the reverb, rendering worthless the innate skills that Marty, Miles, and others had gleaned over thousands of hours of hardbat exchanges.

"Like Willie Mays taking off at the crack of the bat," Reisman explained, "we were all conditioned to react to the sound of the racket hitting the ball. But with Satoh that was impossible. Suddenly, we were all deaf-mutes in a game that required dialogue."

Reisman faced Satoh in a preliminary round. He managed to win the first game before losing the match in four. "He gave me that little bow; a nice man, I thought, but oh how I hated him."

Miles was less charitable. "This abused, apologetic homunculus who had wrecked the game in 10 days was never seen again in international play," he wrote.

Reisman tracked down Satoh in Japan to revenge his ignominious defeat. But he couldn’t or, rather, wouldn’t adjust to this alien form and eschewed the “fraud and deception” of the sponge paddle with only rare exceptions. His obstinacy puzzled friends and opponents alike, leaving them to wonder why he didn’t at least try to change. Marty refused to be swayed.

An anguished Miles wrote that the newfangled serve-and-volley affair of speed and spin “reduced a sport to a game,” and lamented that table tennis was no longer attractive to the TV networks. Their disapproval did little to halt the sponge revolution amid rule changes that standardized the thickness of the sponge on the paddles and, eventually, led to the introduction of the “sandwich rubber” (sponge covered with ordinary rubber). “Overnight, former champions were has-beens,” noted Reisman, arguing that sponge was a boon for manufacturers because the rubber wears out quickly and has to be replaced frequently.

Not long afterward, as ping pong emerged as the No. 1 spectator and participatory sport in China, their top players usurped Europe and the U.S. in the rankings. Miles reached the semis in singles at worlds in 1959, beating two Red Chinese opponents (as he called them) before losing to a third. Reisman won his only U.S. singles titles in 1958 and '60.

Their window to a world title had closed as millions of Chinese heeded Mao's admonition: "Regard a ping-pong ball as the head of your capitalist enemy. Hit it with your socialist bat, and you have won the point for the fatherland." The Great Helmsman apparently didn't make a distinction between sponge and hardbat.

Through highs and lows, from the sartorial glamour of the '50s to the polyester shorts of the 2000s, Reisman and Miles never abandoned their obsession. They cobbled together careers in ways that mirrored their personal stylings. Miles took on an ambassadorial role. He gave demonstrations touring with Bob Hope on the USO circuit. He sold branded paddles and equipment for Sears and Montgomery Ward. He wrote a table-tennis manual for beginners and provided commentary for Wide World of Sports. He served on the executive board of the U.S. Table Tennis Association (now USATT).

Marty embraced the role of ping-pong jester, the "Danny Kaye of the sport," with élan. He and doubles partner Doug Cartland put on exhibitions, gave lessons, and played for stakes from Hanoi to Delhi to Hong Kong, from Phnom Penh to Singapore to Manila, from Osaka to Rio to Okinawa. No bet was refused. (They also won the bronze medal in men's doubles at the ill-fated 1952 worlds.)

They reportedly earned $500 a week touring with the Harlem Globetrotters through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, entertaining thousands of fans at halftime with neat tricks. They played with five balls going at one time and made behind-the-back returns. Marty's pièce de résistance was to place a cigarette at the opposite end of the table and then, crushing the ball with his powerful forehand, break the cigarette in two.

Escapades of varying legality cemented his stature as a ping-pong pirate. He bought nylon stockings and ballpoint pens in the U.S. and re-sold them at a premium in war-torn countries. He bragged about making approximately 25 trips smuggling gold bars in Asia by stuffing the bulky bullion into the pockets of a muslin vest. He earned $1,000 to $2,000 per journey and used the funds to finance "all sorts of money exchanges and black-market activities."

In Money Player, he relates a tale about a mattress factory owner from Nebraska who called him out of the blue to help win back the $80,000 he'd lost playing ping pong against another local. Pretending to be a visiting baby-crib salesman, Marty flew to Nebraska and hustled the mark out of 20 grand. (Marty received one-third of the loot.)

Not all of his ventures were successful. Marty liked to say that he made three fortunes and lost three fortunes.

In 1958, about to marry his first wife, Reisman tried steady employment for the first time: selling shoes at B. Altman's department store for $50 a week. He lasted four weeks before he was fired. "I had to be at work at precisely the hour I was used to going to bed: 9 a.m.," he complained.

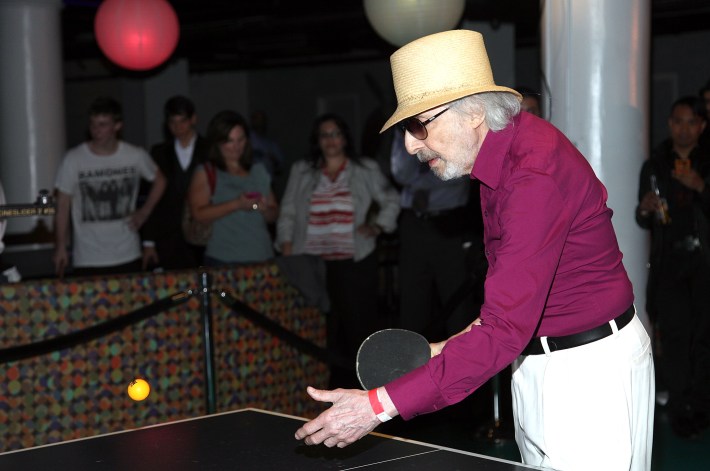

Marty returned to his roots and bought Riverside Table Tennis, reportedly for $6,000. He turned it into a latter-day Lawrence's, a neighborhood hangout that allowed him to give lessons, charm reporters, work on his fluorescent tan, survive another nervous breakdown, divorce his first wife and marry his second. Always immaculately outfitted in tailored slacks, tinted aviator glasses, and a Panama hat, Reisman, ever the showman, might casually remove a $100 bill from his wad and use it to measure the height of the net.

Reisman and Miles were settling in their roles as éminences grises when geopolitics unexpectedly engulfed table tennis. During the 1971 world championships in Nagoya, the top-ranked Chinese team invited the U.S. contingent (ranked a lowly 23rd) to tour the mainland and play a series of exhibitions. Miles was covering the event for Sports Illustrated; he and the other "accidental diplomats" were the first Americans to journey behind the bamboo curtain since the Communist takeover in 1949. They posed on the Great Wall for the cover of Time, their trip marking an unlikely if encouraging step in the rapprochement between the world's most powerful nation and its most populous.

"They did, with sponge racquets, what the Paris peace talks, striped pants and Homburg hats, and the State Department couldn't do in decades—unthaw one-quarter of the world," Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray quipped. "Not since Marco Polo or Admiral Perry had so few brought back so much from the Orient."

The Chinese squad returned the favor the next year, playing matches across the U.S., while President Richard Nixon toasted Premier Zhou Enlai. Glenn Cowan, the long-haired young star from Los Angeles who stepped off the team bus in Beijing looking like he was going to Coachella, wrote an instructional book and hit the talk-show circuit.

With "The Ping Heard ‘Round the World" generating enormous global publicity as a symbol for peace, the sport seemed poised for a comeback. Optimistic USATT officials predicted that the surge would resemble the chess boom that followed Bobby Fischer's victory over Boris Spassky in 1972. (Marty had placed a winning bet on the chess match because he'd seen Fischer play ping pong at the club, and knew him to be "a remorseless conscienceless ice-blooded castrater who was not satisfied simply de-nutting an opponent; he had to taste and savor and chew and, in the end, spit out the ruined remains.")

The rally fizzled quickly, unlike the chess boom. Cowan's dreams of establishing a national chain of table-tennis parlors went nowhere, and he eventually succumbed to mental illness. Soon enough, ping pong was relegated to America's musty basements and lumped together with casual pastimes like pool, darts, and bowling.

During the initial frenzy of Ping-Pong Diplomacy, journalists from Esquire, the Washington Post, the New York Times and the New Yorker came to Marty's club to interview him about the developments because, as he truthfully claimed, "I'm more famous in Hong Kong than I am in New York, my home town."

But he was persona non grata on the circuit due to his festering spats with USATT authorities going back to the 1940s. Marty was 15 years old when he handed $500 to a guy he thought was a bookie "to put on myself." Turns out, he had mistakenly approached the president of the USATT, that "most righteous of officials." Marty was escorted from the premises. Fines and suspensions followed, and USATT denied him "the opportunity to play in all the tournaments he should have played in," according to Jacobson.

Their refusal to include Marty was a missed opportunity for the sport. "I'm legendary in my own time—I'm serious about this—the crowds shift whenever I go out and play," he complained to Post reporter Kenneth Turan.

When Marty published Money Player in 1974, he blasted the USATT "bureaucrats … who could not be expected to see beyond a rule book." The organization "did not want 'controversial' players … playing against the World Champion Chinese, even though I had ties and close friendships going back a long time with a number of top Mainland Chinese players."

When his first club shuttered, he opened a second version across the street. That one closed in the early '80s, but he continued to hit at tables around New York City, including one that editor-publisher Sir Harold Evans and his wife, Tina Brown, set up in the basement of their Upper East Side apartment building. Into his 70s and 80s, still "thin as a string bean," according to Jacobson, Marty boasted that his arsenal of strokes remained mechanically perfect.

Perhaps his greatest contribution to "the game that infects the bloodstream," as he called it, was his lifelong advocacy for the old-school paddle. His devotion helped launch a modest contemporary revival at places like Spin, which advertises itself as a "ping-pong social club" and has opened locations first in New York City and then across the country. (Order yourself the signature "Marty Reisman," a Mezcal-based cocktail.) Whether Chalamet can provide another boost to the sport remains to be seen.

More importantly for Marty's legacy: The USATT decided to revive hardbat events at the national tournament. The men's singles hardbat winner in 1997? None other than Marty Reisman. He was only 67 years old.

Twick-tock, twick-tock, twickety-tock.