The Cleveland Browns' victory over the Eagles on Dec. 3, 1950, marked a changing of the guard. The upstart Browns, in their first year in the NFL after four years of dominance in the All-America Football Conference, beat the Eagles for the second time that year, eliminating them from the playoffs. The Eagles had won the two previous championships, and were the flagship of the league, which at the time had its offices in Philadelphia, Commissioner Bert Bell’s hometown.

The Browns' 13-7 win at Cleveland Stadium was perhaps even more notable for another reason: It remains the last time an NFL team won without recording an official pass attempt.

The weather was decidedly not conducive to an air raid on the lakefront, with rain and wind, as snow continued to melt from what in Cleveland is still called the Thanksgiving Blizzard. But there’s another reason no passes were thrown: Head coach Paul Brown wanted to prove that his team was so much better than the Eagles that he could beat them with one hand metaphorically tied behind his back.

The history of professional sports in America is a good example of survivorship bias. It only seems like the current major leagues were fated to survive, but there have been plenty of challenges from competitor leagues, some more serious than others. Competing leagues generally raise the cost of labor—which was kept artificially low for decades, thanks to the reserve clause in baseball, which was imitated in other sports. Although pro sports now seems like a money-printing monolith, that wasn’t always the case.

And so it was in 1949, when the NFL absorbed three teams from the All-America Football Conference. While the postwar economy was starting to hum again, that hadn’t extended to pro football, which was still not as popular as the college game.

The AAFC was the brainchild of Arch Ward, the Chicago Tribune sports editor. There are sportswriters from the era who are regarded as brilliant wordsmiths and storytellers. Ward was never one of them. That didn’t seem to bother him in the least. He was regarded as a power broker and an innovator, the confidant of some of the greatest figures in sports history. He’d gotten his start as a student at Notre Dame, doing publicity for football coach Knute Rockne.

It was Ward who’d suggested a baseball all-star contest at Comiskey Park in Chicago in 1933. Originally intended as a one-off, the All-Star Game has become an annual tradition. Ward also organized the Golden Gloves amateur boxing competition. In the 1940s, he decided another pro football league was necessary. The AAFC would feature teams in cities that weren’t served by the NFL, like Buffalo, Miami, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. On Sept. 6, 1946, the eight-team league launched with the Cleveland Browns—named for their already accomplished coach, Paul Brown—who hammered the Miami Seahawks, 44-0.

Brown, who’d won state and national titles at his alma mater of Massillon High School and then won Ohio State’s first national championship, had created a dynasty in Cleveland. The Browns dominated the league, playing a perfect season in 1948, but were such a juggernaut that interest started to wane. Nobody wants to watch a league with only one contender.

Meanwhile, the NFL seemed to be wobbling as well. The league was pumping money into Green Bay; the luster of Titletown was fading, not to be recovered until the Packers hired Vince Lombardi a decade later. The Steelers were also taking on water, as were the Lions, as recalled by Brown in his autobiography, PB: The Paul Brown Story.

Following the 1949 season, a deal was reached: Three teams from the AAFC would join the NFL: the Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts. The Browns and the 49ers had just played in the championship game, and were the hottest rivalry in the AAFC. (The Colts were not quite as stable, and folded after just one year in the NFL.)

Additionally, the New York Yankees of the AAFC effectively merged with the New York Bulldogs of the NFL, and played as the New York Yanks before an ill-fated move to Dallas for the 1952 season—the subject of a new book, A Big Mess in Texas. Those Dallas Texans, not to be confused with the later AFL team of the same name, limped through one season before collapsing. That team’s remnants were moved to Baltimore to become the second iteration of the Colts, whose lineage exists to this day.

The Browns were the only champions the AAFC had known. But the NFL’s old guard didn’t take them seriously.

“Our weakest team could toy with the Browns,” said George Preston Marshall, the unrepentant racist who owned the Washington team.

Browns quarterback Otto Graham took the talk with a certain aplomb. When the AAFC was referred to as defunct, he said, “The AAFC is not defunct. We just absorbed the NFL.”

Marshall fired back, “You probably won’t even have a job next winter. Maybe you’d like to drive one of my laundry trucks.” (Ironically, Graham’s only head coaching job in the NFL came in 1966, when he was hired to coach … Washington. Marshall was still putatively the owner, but he was in declining health and not involved in running the team's day-to-day.)

“He was obnoxious,” Paul Brown said of Marshall in his memoir. That autobiography remains eminently readable, in part for how few punches he pulled. He was fined $10,000 by the NFL for what he wrote about Browns owner Art Modell, the man who fired him. “My father’s rebuttal was ‘But it’s true,’” Mike Brown recalled.

Following an undefeated preseason, the Browns were scheduled to open the season at the two-time champion Philadelphia Eagles. Commissioner Bert Bell might have viewed the game as a chance to prove the NFL’s superiority. We don’t know, because he remained assiduously diplomatic on the topic. But he definitely saw the game, billed as football’s World Series, as an opportunity for a big crowd. The Eagles’ home field at the time was Shibe Park, with a football capacity of only around 32,000. The Browns-Eagles game would be held instead at Municipal Stadium, which could seat 102,000. Preorders for tickets started in June.

But while Bell believed the better part of valor was discretion, Eagles head coach Earle “Greasy” Neale had no such restraint, volunteering that he didn’t even bother to scout the Browns before the season. “They are just a basketball team,” he said. “All they can do is throw the ball.”

The Marietta, Ohio, native was already an accomplished football coach, with stops in colleges throughout Appalachia, including most notably at Washington & Jefferson, taking them to a Rose Bowl in 1922. Neale had also had a career in professional baseball, winning a World Series with the 1919 Cincinnati Reds, who beat the notorious Black Sox. As a football coach, he had built the much imitated Eagle Defense, progenitor of the 4-3 defense, which can still be seen on NFL Sundays. Neale believed it could stop any team, even one quarterbacked by the elite Otto Graham.

If the Eagles didn’t scout the Browns, the Philadelphia Inquirer did, sending reporter Mort Berry to preseason games. He was impressed by what he saw. “Just how good they’ll be by Sept. 16, when they make their National Football League debut against the Eagles in a classic to be held with the co-operation of the Inquirer Charities at Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium, is a thought that must make Eagles’ fans shudder,” Berry wrote after the Browns’ second preseason game, a 34-7 drubbing of the Colts at Nippert Stadium in Cincinnati.

“You will need a lot of touchdowns to stay in the game with the high-scoring Browns a week from Saturday,” he warned the Eagles after the Browns beat the Steelers 41-31 in the preseason finale at the old Rockpile, War Memorial Stadium in Buffalo. “Show up prepared for the game of your lives.”

“They aren’t human,” said Lions tackle Chet Bulger, who saw the Browns up close in a 35-14 preseason loss at the Rubber Bowl in Akron.

A crowd of more than 71,000 fans showed up for the Saturday night opener against the Eagles. The Browns, one of the first teams to regularly use an airplane for travel, flew into Philadelphia the day before. “The Browns are more conscious of air than any team in football,” Berry wrote, referring to the team’s wide-open passing game.

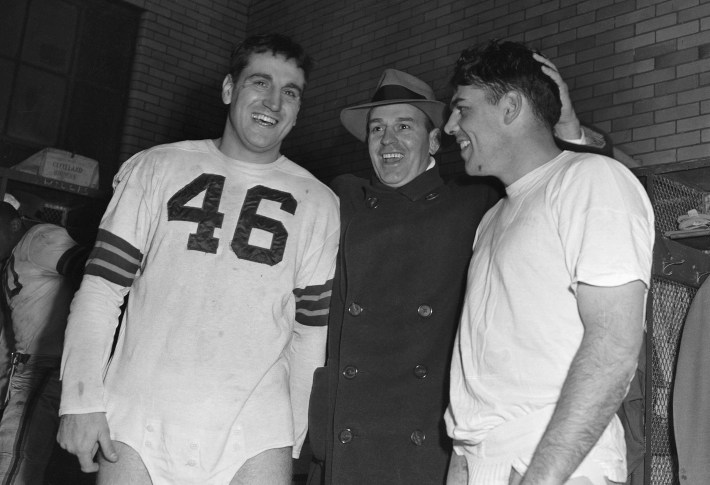

After the Eagles scored first, the Browns unleashed the air raid. Brown said he made it a point to spread the Eagle Defense by spacing his offensive linemen, taking advantage of the lack of a middle linebacker to throw passes over the middle. Graham threw touchdown passes to three different receivers, and ran for another. The Eagles outgained the Browns on the ground 148-141, but were no match for their passing game. Graham went 21-for-38 for 346 yards. Neale noted later that Graham had a knack for throwing his receivers open.

“Greasy Neale's awesome monsters, the most feared defensive team around the last couple of years, just couldn't get untracked in trying to cover Graham’s deadly aerial darts,” wrote Dick Cresap in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin.

“So the Eagles now have their work cut out for them as they seek to regain prestige, which has been theirs two years running, as pro football's best team,” Ed Delaney wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News.

Neale believed—and said as much—that the Browns had gotten special treatment in the merger, being able to take the best players from the AAFC teams that folded. They would have nearly three months before their rematch. That was more than enough time for Paul Brown to get good and stewed over Neale running his mouth.

Dec. 3, 1950, was a wet day in Cleveland. The city had been paralyzed the previous week as a cold front blew in, dropping nearly two feet of snow, leading to closures of businesses, schools, even the airport. The blizzard stymied ticket sales as well. More than 60,000 fans were initially expected for the Eagles-Browns rematch, but attendance was closer to 37,000.

Temperatures had risen into the 50s, and snow was melting quickly enough that flooding was a concern along the Cuyahoga and Chagrin rivers. Showers continued Sunday, making the field at Cleveland Stadium a muddy mess. Neale stood on the field and told reporters he was afraid he’d drown in one of the marshes around the Eagles’ bench.

The Browns got off to an early lead when defensive halfback (a 1950s-era hybrid between cornerback and linebacker) Warren Lahr stepped in front of Steve Van Buren to intercept a wounded duck from Tommy Thompson for a 30-yard pick-six on the Eagles’ third play from scrimmage. It was the first of four turnovers for the Eagles that day.

That lead was crucial to Brown’s game plan, which didn’t just call for beating the Eagles—he wanted to humiliate them.

“Coach Brown said, ‘As long as the score is tied or we’re ahead, we’re not going to throw a pass,’” guard Alex Agase said afterward. “And we didn’t.”

The Browns instead played the field position game, with Horace Gillom punting 12 times—several times on third down just in case there was an issue handling the ball.

Lou Groza booted a pair of field goals to stake the Browns to a 13-0 lead, giving him 12 field goals for the season and setting a new NFL record. It was an era before specialization, and Groza was a Pro Bowl offensive tackle, but he became known as “The Toe,” serving as the team’s placekicker for an astonishing 20 years. When he retired in 1967, he was the last of the original Browns.

The Eagles were able to put together one drive at the end of the game, but the outcome wasn’t in doubt by that point, and the Browns won, 13-7. They had a total of 68 yards on offense, one first down, and no pass attempts. Just like Paul Brown drew it up.

“It was a silly grandstand play,” Brown said after the game. “But I wanted to prove we could win the hard way.”

“Their reign as the pro gridiron kingpins has come to a sorrowful ending after their winning of three divisional titles and two league crowns,” the Daily News wrote of the Eagles. But the Browns were still in the fight of their lives. They faced another must-win game the following week against Washington, and hammered them 45-21 to set up a tiebreaker game against the Giants.

The Browns won a coin toss to host the game, and it was a frigid day on the lakefront—cold enough that the Browns wore sneakers, except for Groza, who wore one sneaker and one football shoe, minus the cleats, for kicking. He booted a pair of field goals and the Browns scored a late safety to win 8-3. Otto Graham was 3-of-8 passing for 43 yards, and the Browns were heading to the NFL Championship Game in their first year in the league.

They would host the Los Angeles Rams in the championship game, and as the fourth quarter started, the Browns were trailing 28-20. But Graham led a drive that required three fourth-down conversions, and culminated in a touchdown pass to Rex Bumgardner. The teams exchanged punts, and the Browns started driving again. They were within Groza’s range when Graham fumbled. “Don’t worry about it,” Brown told him. “We’re going to win.”

The Rams went three-and-out, and the Browns drove again, setting up Groza for a 16-yard game-winning field goal.

The Browns' 30-28 victory showcased the aerial stylings of Graham and Rams quarterback Bob Waterfield. Commissioner Bert Bell called it “the greatest football game I’ve ever seen.” Graham said the season was the highlight of his career.

That offseason, Brown was offered the head coaching job at the University of Southern California, which he declined. His name was also mentioned for a return to Ohio State, and although there was widespread acclaim for him to take that job, Brown declined that one, too. The Buckeyes instead tapped another Eastern Ohio native, the coach at Brown’s alma mater, Miami University. Although there were factions that were upset with the hire of Woody Hayes, it seemed to work out pretty well.

Brown stayed with his namesake NFL team until his unceremonious removal by Art Modell in 1963, then started a team in Cincinnati: the Bengals, who are still owned by the Brown family.

Still, in an illustrious and innovative career, nothing beat 1950.

“Our first season in the National Football League," Brown later wrote, “was the most satisfying football experience of my life.”