In 2020, a group of scientists collected eight ocellate river stingrays and put them in the stingray equivalent of an apartment: a 343-gallon tank of balmy water subdivided into several rooms. The stingrays, which came from the Frankfurt Zoo, were brought to the tank for a rather serious purpose. They were there to learn arithmetic—to add and subtract by one item. If the rays had to do math, at least they would be doing so in luxury.

Although this task must have been unexpected for the stingrays, it was not unprecedented for the scientists. Humans attempting to teach animals to count is somewhat of a historical practice. In the early 20th century, a horse named Hans sailed to fame by solving calculations by tapping numbers or letters with his hoof along with his trainer, a mathematics teacher named Wilhelm von Osten. Hans could count the number of people in an audience, perform arithmetic, and even read a clock. There certainly were skeptics, but Hans proved his abilities over more than a year of investigating by the German board of education. The ruse only fell apart when biologist and psychologist Oscar Pfungst revealed that Hans could only answer questions that questioners also knew the answer to; the horse was reading nearly imperceptible signals in his inquisitor's face. After Hans's hoax was found out, he fell out of stardom and was drafted into World War I as a military horse and either killed in action or eaten by hungry soldiers.

In more recent research, scientists have found that many animal species have or can learn numerical cognition, such as counting or distinguishing one quantity from another. Although this list includes obvious candidates like chimps and gray parrots, more and more species have made the cut as cognition scientists turned their lenses toward fish. And this is how the eight ocellate river stingrays came to live in the lab of neuroethologist Vera Schluessel at the University of Bonn in Germany.

Schluessel's research group had tested the cognitive abilities of ocellate river stingrays for years and were familiar with the organisms, according to Nils Kreuter, a marine biologist at Uppsala University in Sweden who was a former student in Schleussel's lab. The stingrays swims in South American rivers and appear in a number of different colors and patterns, from sparse dots to marbled eye-like spots. In 2019, another group of scientists tested honeybees' abilities to add and subtract, and published their results—the honeybees can count!—in a paper in the journal Science Advances. Schluessel, Kreuter, and colleagues adapted the honeybee experiment for eight stingrays and eight bony cichlids, freshwater fish native to Lake Malawi in Eastern Africa, and published their results in the journal Scientific Reports. "As elasmobranchs represent the oldest lineage of vertebrates it is one piece of the puzzle to understand the evolution and development of cognition," Kreuter wrote in an email, referencing the rays.

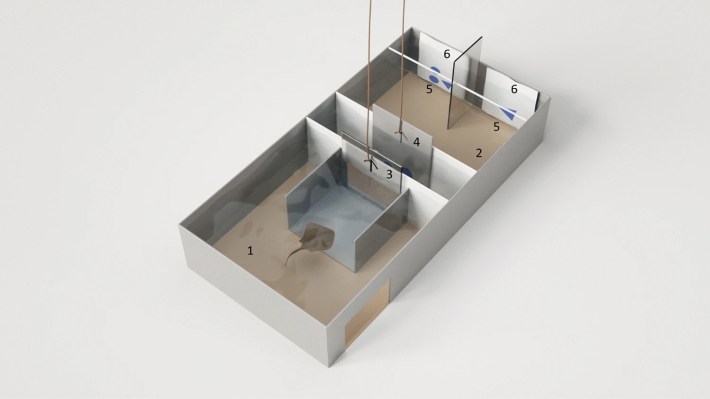

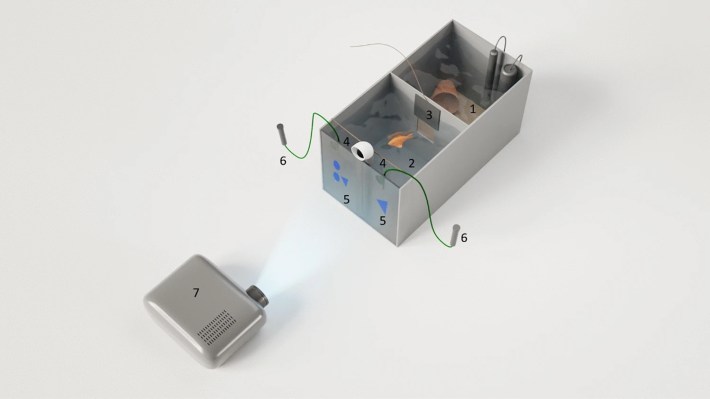

Once the stingrays and cichlids were in their tanks, the scientists began familiarizing them with the simplest concepts of arithmetic. They showed the fishes an image of up to five shapes: squares, circles, triangles. Although the shapes were different sizes and mixed together, they were all either yellow or blue. The scientists trained the cichlids and stingrays to associate yellow with "subtract one" and blue with "add one." The cichlids and stingrays each had five seconds to memorize what they saw. Then, a gate would open to another room in their tank and the fish had to choose between two new images: one with an additional shape, and the other with one fewer shape. If the shapes the fish initially saw were blue, they were supposed to pick a second image with an additional shape—to "add one." If the shapes the fish initially saw were yellow, they were supposed to pick a second image with one fewer shape. Whoever swam to the right picture received a treat: cichlids got pellets and stingrays received earthworms, shrimps, or mussels. Wrong answers received nothing.

Not every fish understood the rules immediately, and some fish never grasped it all. But six of the eight cichlids and four of the eight stingrays managed to learn the rules. And even though the stingrays had a poorer general showing, the four that did complete their training had a higher accuracy rate than the cichlids. But both species had an easier time adding than subtracting.

To ensure the fish were not simply memorizing the images, the researchers posed an arithmetic question with specific values the fish had not seen in their training: 3+1 or 3-1. The fish still often chose the right answer. And in an extra test where the stingrays and cichlids were shown second images that showed a choice between one extra shape and two extra shapes, the fish picked the image that showed one extra shape—following the "+1" rule and not simply picking the higher quantity. The results were surprising, the scientists wrote, as stingrays and cichlids do not have an obvious behavioral or ecological need to possess, let alone excel in, arithmetic.

The brains of humans and other mammals have what's called a cerebral cortex, which helps us carry out complex cognitive skills. Fish lack this structure. But their ability to perform this simple arithmetic suggests a cerebral cortex is not a requisite for such activities, the authors write. "It shows once again that fish are smart animals and that humans tend to underestimate them," Kreuter said.

Some scientists who were not involved with the research expressed reservations toward the paper's interpretation that the stingrays were actually counting, reported Sophie Fessl in The Scientist. But whether the experiment was a true test of addition and subtraction abilities, it still put the stingrays through a ringer of decisions involving visualization and memory, Schluessel told Fessl.

Other marine animals—whose cognitive abilities we have never tested—have bodies that mathematicians today are still trying to unravel. And even though, contrary to popular myth, the average nautilus's shell is not a true golden spiral, it is still a logarithmic spiral, according to a story in the magazine Nautilus (no relation). Though the mollusk may never do geometry, I would argue they are more of an expert than I am, a creature with a brain whose technical ability to do math was easily vanquished by a deep, years-long loathing of the subject.

In the wild, it seems an ocellate river stingray might live its whole life without ever having to solve an arithmetic problem. "For what ocellate river stingrays would need a particularly good numerical ability is not known," Kreuter said. The rays do not hunt or engage in mating-related behaviors that might require numbers, such as counting stripes or eggs. But perhaps the smartest thing in the world is to have the ability to do math and to never, ever use it.