Fifty-one days ago, I had a very long and very complicated jaw surgery. I’m basically fine now; you don’t need to worry about me. But I know exactly how many days it’s been because obsessively crossing squares off my calendar is the only way I’ve been able to stay sane through the recovery process. That, and documenting every horrific phase of this so that some day I can look back and laugh about it. That day has not yet come. I’m typing this sentence after being forced to stop eating risotto because my tongue started bleeding in three different spots, from fishing wayward rice grains out of my wired-in splint. When I told Barry I was writing about my surgery and recovery, he asked me what my angle was. “This sucks butt?” he suggested. Pretty much.

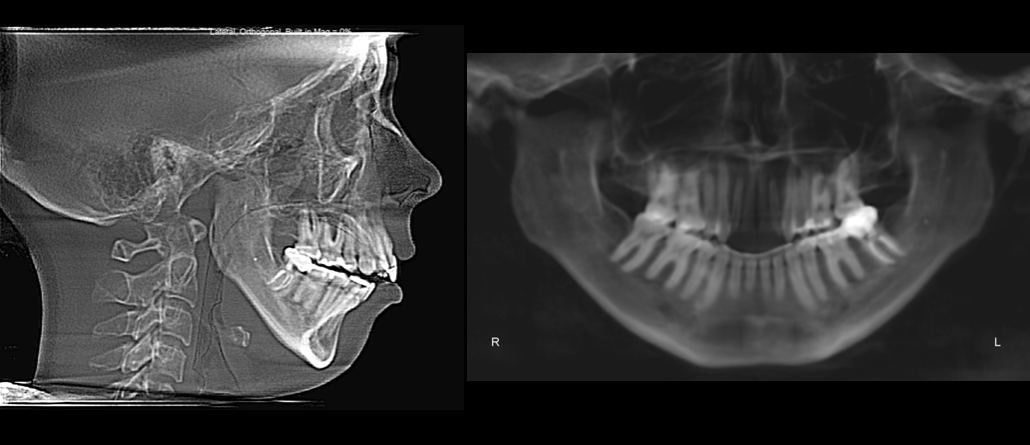

When I was 16 or 17 years old, I found myself back at the orthodontist because I started noticing my teeth were hitting differently. I had braces when I was 10 and 11 to fix my very prominent buckteeth, and the braces had worked. My teeth were perfect. Julia Roberts was my favorite actress then and I had a smile that rivaled Julia’s. But now my jaw joints were hurting, and my bite felt funny. I went to my orthodontist to see what was up, thinking I probably was just clenching my teeth and needed a night guard. Nope. The scans showed that my jaw was doing this rare, weird thing. My orthodontist sent me to an oral surgeon to investigate further. He confirmed what my orthodontist thought: Idiopathic condylar resorption. Translation: My jaw joints were eating themselves, and for no apparent reason.

After I got my diagnosis I learned that ICR is most common in teen girls and the only way to fix it is with surgery, but I’d have to wait until all the damage was done, until whatever little demon was causing trouble in there had worn itself out. So I waited, as my bite kept changing. My jaw joints slowly shrunk and my cute little chin moved farther and farther back, until I hardly had a chin to speak of. I couldn’t close my lips. I couldn’t breathe out of my nose very well. I couldn’t bite into a sandwich or a slice of pizza. I had to use a fork to eat a hamburger! I hated eating in front of people, because I could only use my back four molars to chew and I was constantly dropping chunks of food out of my mouth. My weird open bite soon became my party trick: I would stick my tongue out between my completely shut teeth and wiggle it as my friends looked on. I looked like a little lizard.

I got scans of my jaw every six-ish months to assess the destruction. By the time I was 21-ish, the jaw had eaten its little heart out. I could now get surgery whenever I was ready. But I wasn’t ready and likely would never be ready-ready. I was graduating and moving to New York. When would I ever have the time to handle this?

My specific problem meant I would need a total joint replacement and upper jaw surgery, both done at the same time: Two titanium joints on both sides that would bring my lower jaw forward an entire inch into its previous and proper position, and a LeFort osteotomy, in which the doctors saw (I don’t actually know if “saw” is the correct verb here and I don’t truly want to know) my upper jaw into three pieces, and then fit the pieces back together in a new position. In order to do it, the surgeons have to stretch the facial nerve that runs along your jawline. That nerve does not like to be disturbed, so it rebels and goes on strike and there’s usually temporary loss of facial movement and feeling after surgery. It could take months to return and there’s no guarantee it will come back fully.

The surgeons don’t have the technology to show you a mockup of what your face will look like post-surgery, and I was really afraid I might hate my face or have a hard time adapting to my new look. Most people I’d seen who got a similar surgery ended up looking way hotter, but I’d also seen a YouTuber crying about how she thought her nose was bigger post-surgery. There’s a surprisingly large community of jaw surgery TikTokers out there that will show you all the graphic details and really fill you with dread. On top of all that, my mom’s brother died during a routine surgery when he was 12 years old. We’re not sure what happened, but the most likely cause is a genetic condition called malignant hyperthermia, basically an allergy to the most common forms of general anesthesia. None of my family knows if any of us have it, because the testing is very complicated, so we’re all terrified of having surgery. I’d never had surgery before and with MH looming over my head, I decided to put this off because my jaw problem was not life-threatening. It was inconvenient and frustrating and I didn’t always like how my face looked, but the average person wouldn’t know anything was wrong with me if I didn’t tell them.

Sure, I hated my profile, the way my chin sank back into my neck and made me look like a turkey. I hated the way Twitter trolls regularly commented on my gummy smile and big teeth, comparing me to a horse girl or once, Rufus, the naked mole rat from Kim Possible. But I learned how to smile in pictures and how to angle my chin so it looked a little more there. I hated how my open bite gave me a slight lisp, and I hated getting regular sinus infections and having seasonal allergies pretty much every day from mouth breathing. But none of this was devastating enough for me to seriously consider going through surgery hell.

Then the pandemic arrived and everything slowed down. I got laid off, I didn’t travel as much, and then I needed a root canal. A root canal at 27?! I was pissed. It was expensive as hell and my dentist told me that if I didn’t get surgery, I’d soon burn out all four of my molars that were doing all my chewing. I might never have the time to do this again, and with everyone wearing masks no one would even need to know I had braces!

I spoke to an oral surgeon in Chicago, who I’d been referred to years earlier. I started the process with him in the spring of 2021. This time I was sure I wanted to do it, until I met his boss, the head of the oral surgery department, who asked me what my main motivation for surgery was. “I want to save my teeth,” I told him.

That’s it? he said. This is not an easy surgery. You need to be really sure that this is what you want to do.

I was offended by his response. I wasn’t uneducated about this. I’d been learning about my condition for years at this point and had put surgery off for so long because I knew how bad it was going to be.

“Well, I also want to breathe better, and be able to chew things normally, and not have a lisp and be able to shut my mouth again!”

OK, he said, nodding at me. Now I wanted to do it just to prove him wrong.

It turned out he was onto something, because as the months slowly went by, I had plenty of time to doubt my decision. I almost quit and pulled the plug three or four different times. Once when I was told I’d need braces for a year in advance (that was incorrect), another time when I was told I wouldn’t be able to have long conversations (a.k.a. interviews!) for five weeks (mostly untrue). In September, my surgeon submitted the order for my titanium joints. Of course there’s only one company that is FDA-approved to make the joints, so I had to get in line and wait. In February, I finally got my surgery date: May 4.

A week before surgery, I got my braces on. I was surrounded by kids discussing their eighth-grade graduations, and I was silently fuming. At one point in the appointment, another orthodontist came by and checked my resident’s work. “Bite down,” he said. I bit down. He waited. “I am biting,” I said.

“Oh, you are going to love your results from this surgery,” he said.

“Yeah, well, fuck this,” I said, a bit louder than I meant to. But I didn’t regret it. This sucked, and I wasn’t going to pretend like everything was all fine and dandy. I wanted everyone to know I was not pleased and I hope I scared all the little tweens in the room too.

When I finally left the orthodontist with my bag of special floss, I called my mom and burst into tears. The brackets were irritating me, I could hardly talk with the surgical hooks sticking out in every direction, and the reality of what was coming in a week hit me hard. I got on my bike to go home and I cried for most of the four miles. I taught my dance classes that night, my last dance night before my long surgery break, and as I said goodbye to all my dancers I found myself actually wondering, what if this is the last time I see them? What if I don’t make it out of this surgery? Rationally, there was basically no risk. None of my doctors were concerned at all. But I’m not a rational person. I’m certainly not a scientific person. I am emotional, dramatic and impulsive. It was the elective aspect of this surgery that was slowly destroying me. I wished a doctor would just say: Kalyn, you have to do this.

That night I booked a flight to Florida for the next morning. I was a mess after the braces experience and I needed to visit my mom and get in some sunshine before surgery. She picked me up from the airport, and I cried again as I told her how I was worried that I might die. “You don’t have to do this,” she told me. “It’s OK to change your mind.”

I knew that was true, but I’d already put in a year’s worth of doctor appointments, battled through insurance pre-authorization (not easy!), put down a $600 deposit for braces, and waited months for these stupid joints. I’d made all my plans for medical leave from work, my mom was coming to take care of me for two weeks, and all my Amazon packages of syringes and protein powder and peanut butter and bone broths and ice packs and a pill crusher had arrived (thank you to the TikTokers for properly preparing me). I’d been in therapy for two months discussing all my fears and anxieties. My bathroom mirror was filled with hopeful post-it note affirmations that I repeated to myself daily, though they sometimes took the form of questions.

MY FEAR IS FADING BY THE DAY.

MY SURGERY WILL GO WELL.

NO MATTER HOW SCARED I AM, I WILL GET SURGERY.

I AM READY?

“Do you think I will chicken out?” I asked my stepdad.

“Not if you have any common sense,” he said.

“But that is the question,” I pointed out.

I cried a lot.

On the day of surgery, I woke up at 4 a.m. to chug a Gatorade before my deadline to stop drinking. I showered with antibacterial soap and then was forbidden from putting on any lotion or even deodorant. I cried as I shut the door to my apartment, thinking about how miserable I would be when I returned. When my mom and I tried to park in the hospital’s garage, the ticket reader wouldn’t scan our ticket to let us through the gates. Turn around! I said. But then a woman who worked at the hospital walked by and scanned her monthly pass for us. Oh God, I thought. I really have to do this.

My legs started shaking as I checked in for pre-op. I was hiding in the bathroom when the nurse called my name to come to the back. I started crying again as the nurses gave me pre-operation directions to use the antibacterial wipes and change into the surgery gown and surgery hairnet and surgery socks. Two different nurses came over to hug me because I looked so upset.

We still had an hour to kill before surgery. My mom wore her special affirmation shirt for me, embroidered with the words, She Can, She Will. Normally I hate that shit, but boy did I need it now. One of my friends updated our group text that I was in fact at the hospital: She was stalking my location on Find My Friends to make sure I wasn’t going to run away.

They started putting some relaxing juice into my IV even before they wheeled me back. I asked if I could bring my headphones with me so I could listen to music until I was totally out. My resident said no, but offered to play music from his own phone while they wheeled me to the operating room. “What do you want to hear?” he asked.

“Umm, the Mamma Mia soundtrack,” I said instantly. ABBA always makes me happy.

“OK,” he laughed.

I remember getting wheeled back, and then everyone lifting me onto the operating table. By the chorus, I was out.

When I woke up, I heard the doctors all talking around me. I blinked my eyes open a sliver to see their very blurry outlines. I couldn’t breathe or move my limbs, but I was very awake. My brain was raring to go. I panicked, trying to figure out why I couldn’t breathe on my own but also somehow wasn’t dying or dead. How was this possible? I was totally paralyzed but also extremely conscious and nobody seemed to realize I was awake. I tried to breathe again. Nothing happened. Then I felt someone pull out my catheter, and then my breathing tube. Ohh, there’s the oxygen!

They wheeled me out of the operating room, and I fist-bumped my doctors. Part of me was genuinely surprised to have made it out alive. What time is it? I asked. 9 p.m. The surgery took 10 hours, someone said.

In the recovery room, a nurse strapped ice packs on my face. The doctors didn’t rubber-band me shut then, because I’m claustrophobic and I specifically asked them not to, so my jaw was hanging open. I had no idea how to maneuver it at all. My tongue flopped out aimlessly because I also had no idea what to do with that thing. While I waited for my mom to come back to the recovery room, I took inventory of my face. The only thing I could feel was my forehead. The surgeons asked me to move my eyebrows and close my eyes. Only one eyebrow worked, and I had to work harder to squeeze my eyelid shut on the non-working side. My nose was so stuffed up, so I was mostly breathing out of my mouth. My lips were massive and numb but with my tongue, I could feel the thick permanent plastic splint that covered my upper teeth.

When my mom came back, I told her and my nurse how I was wide awake when the catheter came out. “I felt that shit!” I mumbled at them. My mom had tried to comfort me the day before by saying I probably wouldn’t even remember being in the hospital.

Before long another nurse wheeled me to go get a scan to make sure everything was correct. On the ride to the scan, I started choking on blood in my throat and coughing it up onto my gown. “I can’t breathe!” I tried to say. My mom ran to the bathroom because she felt dizzy seeing so much blood.

The nurse sat me up very slowly, but I still passed out. She shook me awake (rude!) and forced me out of the bed again. I slowly shuffled into the chair and put my chin on the chin-rest, shutting my eyes because I was too dizzy to function. After that nightmare ended, she wheeled me to my room for the night, which is when I learned how much I hate hospitals. They gave me a roommate and told me my mom wasn’t allowed to stay with me. I texted her nonstop. (She informed me the next day that she woke up to 109 texts from me.) Every time I was on the edge of sleep I jolted awake, panicked that I wasn’t breathing. I requested paper and a pen from my nurse, because I couldn’t talk well enough for anyone to really understand me. At 3 a.m. a different surgery resident came in, one I hadn’t met before. He asked me to try drinking water, but I couldn’t figure out how to swallow it, so I started crying again.

By the morning, I hadn’t slept more than 30 minutes. A trail of blood covered the tile floor because every time I stood up to go to the bathroom, my nose bled uncontrollably. Apparently no one bothered to clean it up. My resident came and checked on me at 6 a.m. and gave me a syringe with a catheter tip to use to drink water. This made it much easier to swallow, because I could shoot the liquid down the side of my cheek straight into my throat. He told me I could go home that afternoon if I was able to drink a whole jug of water and eat a bowl of chicken broth. My room was hot and stuffy, and I smelled worse than I ever have before, so I was desperate to get the hell out of there. I syringed and syringed and syringed until it was all gone. I felt like a little gerbil drinking water from that thing gerbils drink from, but I succeeded in my mission and got dismissed at 2 p.m. The hospital person who was supposed to wheel me down to the lobby was late, so I said fuck it, I’m walking out.

The next week was the absolute worst single week of my life. I lost 10 pounds, I hardly slept because I still couldn’t figure out how to breathe, and every time I stood up my heart pounded like crazy. Every time I went to the bathroom, I shut off the light so I wouldn’t have to see my reflection; I was so swollen, I looked like a cross between a grumpy toad and Vito Corleone. I couldn’t move my lips at all, so my mom only understood 40 percent of what I said. I woke up early each day because I was starving but then I could only eat broths or chocolate milk. Even applesauce was too thick. The first time I showered was horrific; I combed through my matted hair and screamed when I tugged on a giant tangled chunk and it came off in my hand. I felt like I had been in a car accident, because my entire body hurt. My neck turned Elphaba green from bruising and I had a scab right between my eyes and more all over my hairline and the back of my neck, where they’d somehow pinned my head into place during surgery. My sideburns were shaved where they made incisions in front of my ears, and I could hardly turn my neck because of the incisions underneath my jawline. I had to buy a special pillow, because one side of my butt was too sore to even sit on. Three times a day, I had to syringe the most evil-tasting liquid antibiotic. My face was so numb, I couldn’t even do my own nasal spray, because I had no idea where the hell my nostrils were. I stained all my clothes because I was constantly drooling. I was constipated for eight days, so my mom split open a laxative capsule and put it in water for me to syringe. I took one shot of it and spit it everywhere, coughing and choking. The medicine burned my throat for at least 20 minutes. This time, both my mom and I cry-laughed.

Nights were scary. I tried so many things to fall asleep. I fine-tuned an elevated pillow structure, ran my diffuser and humidifier, sniffed a Vicks stick for congestion, meditated, put on relaxing lotion, took melatonin, and played Friends on my TV all night long.

Every time I woke up in the middle of the night and looked at my phone to see that only 45 minutes had passed since I was last awake, I whimpered. (I couldn't really cry because my face could not move.) Because I couldn’t sleep, the days felt impossibly long. I felt like a toddler because I had to nap every day at 3 p.m. And even then, I still had daily tantrums because I couldn’t tell if I was tired or hungry. I even looked like a toddler, thanks to my cherubic swollen face and my braces. About four weeks after surgery, I got into an Uber and the first thing the driver said was: “How was school today?”

There were a lot of meltdowns. One day during those first couple weeks, I was syringing a thick soup when the catheter tip came unattached and the soup exploded out of the end of the syringe, coating my glasses and my whole face in ginger turmeric chicken soup. I started laughing, but then the laughing hurt my face, which felt like it was concrete cracking. So then I started crying. This meltdown ended with a hysterical shower tantrum, laugh-crying until I exhausted myself. How long was I going to be like this?! I started crossing off the days to stay sane, marking the various checkpoints along the way but also keeping track of how long I can go without having a meltdown. As I click publish on this blog, it’s been seven days.

A week after surgery, I could syringe thicker shakes with ice cream and peanut butter and watery mashed potatoes. I started eating ice cream two or three times a day for the extra calories, though I was still not gaining weight, which would be fun if it weren’t so terrible. I put ice cream in my coffee, in my fruit smoothies, in my shakes. My mom and I went on longer walks and even went to Anthropologie before I ran out of energy and needed to nap. We saw the musical Six, because it has a run time of only 80 minutes with no intermission, meaning I could make it through without needing to eat anything.

My surgeon said the first two weeks would be the worst, and he was right. Things started to get marginally better. My congestion cleared up and I could breathe through my nose so well it was painful. I was getting so much air into my expanded airway that my throat and nose felt dry. Is this what it feels like to breathe? I asked my mom. It reminded me of what I said to her after I got glasses when I was 8 years old: Trees have leaves?

After two weeks, I could at least drink out of a cup, which meant I was done with the damn syringes. I still couldn’t figure out how to close my mouth by using my actual jaw muscles (I had to use my hand to push my chin back into my neck to force my lower jaw into place), but I could at least go on walks with my smoothies and avoid the weird stares that came when I sat on a park bench and drank out of a big syringe. I still had to nap and if I wasn’t home at naptime, it was an issue. My second follow-up appointment was scheduled for 1:30 p.m. on a Monday, dangerously close to naptime. There weren’t any seats in the waiting room and my surgeon was 30 minutes late. Then I couldn’t open wide enough to put my rubber bands in myself, which frustrated me, and my surgeon scraped off the scabs on my incisions, which made me nauseous. My surgeon said I could start trying to use a spoon, but I felt like I was nowhere near opening wide enough for that. I was tired and frustrated, and it was too cold. I cried the whole drive home.

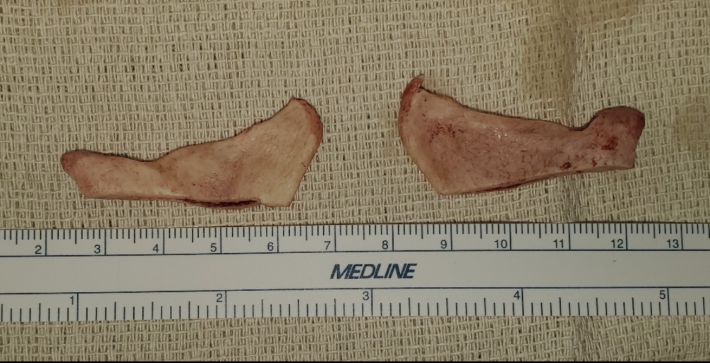

That day, I decided the coming Friday would be Spoon Friday. Surely I’d be able to open wide enough in four days' time. The thing I didn’t understand about this surgery before I got it is that when they put in the titanium joints, they have to strip away most of the existing muscle. "What did you do with my muscles?” I asked the doctor. “Are they in the trash?”

Yeah, we sent some out for tissue samples, but basically, yes.

So my muscles are in the trash, and now you want me to try to open my mouth? It didn’t hurt to try; it was just mostly ineffective. I’d think I was opening it so wide, and then I’d look in the mirror and it’d be just a few millimeters. As the week progressed, it became clear I would not be celebrating Spoon Friday.

At my third appointment, about three and a half weeks out, my surgeon said I could move to a semi-solid diet, like soft bread, potatoes, oatmeal, small pasta, if I was able to open wide enough for it. I wasn’t, but my bite was slowly improving, and so was my speech, though my dad, who had taken the second caretaker shift, started calling me “Slurpee.” Even complete strangers were noticing my progress. At UPS, where I go to print return labels for my online shopping, the cashier said, “Wow, you look so much better! You looked like you were ready to go to bed last time.”

By week three, I was ready to try to reenter society. My dad took me and some friends to a Chicago Sky game, though I had to get special security clearance so I could bring in my own smoothie.

The desperate need for real food started to hit me hard. I had never realized how many food commercials there are. I stopped opening my weekly recipe newsletters. I drove past a Popeyes and immediately rolled up my windows so I didn’t have to smell the fried chicken. On my walk home from Target, I pass by two restaurants with outdoor seating, a hot dog stand and a Mexican restaurant, and I found myself staring at the food so intently that I was turning my head as I walked past the diners. I went to the farmers’ market just to gaze upon my favorite scone. I started a list in my Notes app of all the restaurants and food I want to have during the week after my splint removal, which I am calling “Eating Week.”

I’m not sure how much I’ll be able to chew by Eating Week but I’m trying to be optimistic. My splint is this big fat plastic mouthguard that is wired into my braces on my upper teeth. I can’t take it out and it impedes my eating because everything gets stuck inside it or on the bottom of it. When I eat a sweet potato, it completely coats the grooves of the splint to the point where I'm not sure how much sweet potato I’ve actually swallowed and how much I've rinsed off the splint in the sink afterward. I get the splint removed in five days (eight weeks post-surgery), and as far as I’m concerned, that is when my life will begin again.

I finally celebrated Spoon Friday on the Friday of week four, except that I changed it to Fork Friday because that sounds better and because I’ve realized that I hate spoons. The convex nature of the spoon does not make it a friendly utensil for people like me. Forks are thin and much more approachable. You can do anything with a fork! I used my fork to eat chocolate frosting off a piece of yellow cake and it tasted so good. It was the most exciting thing to happen to me in weeks.

I took five weeks of medical leave and needed every minute of it, but I’m not used to being so unproductive. It’s been hard to get back into my work, and hard to focus on anything for long enough to make progress on it. I still need my naps. All my story ideas seem impossible. But I felt like if I could finish this jaw blog, I could probably remember how to do my job.

The hardest part about this long recovery period is that all of my friends have had the audacity to continue living their lives and traveling and having a good time. This feeling of being alone, that my life has stopped and everyone else is having fun without me, moving on and accomplishing things, has inspired several meltdowns.

Still, I’m glad it’s over and it’s not looming over me anymore. My anxiety feels much more manageable now. I looked at my profile in the mirror last week and I have a chin, which is very cool. I also have two new affirmation sticky notes on my mirror, borrowed from what my yoga teacher said during shavasana in a recent class:

MY BODY IS HEALING THE BEST WAY IT CAN.

EVERY MOMENT I AM ONE STEP CLOSER TO FULL RECOVERY.

My most recent meltdown, and hopefully but probably not the last, came on Day 43. My insomnia was getting worse, because something I added into my diet was hurting my stomach. I was tired all day long and feeling really stuck. My cheeks were—and are—still numb and swollen and my left eyebrow was—and is—still frozen. I’m so sick of my braces and splint always getting in my way. I cried in front of my laptop that morning, wanting to get to work and actually do something but unable to stop thinking of the two more weeks I would still have to endure until I could start chewing normally.

For dinner that 43rd night I decided to try eating ramen. I hadn’t yet been able to eat other pastas without blending them, but maybe these noodles would be skinny enough to lightly chew and swallow.

I stuck my fork in and I finished the whole cup.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter