My son was on a mission. Simon has been walking since December, and he’s getting more confident each day. He’d spotted something, and was scooting down the aisle as fast as he could towards it. He wanted to play in the clothing racks.

They were empty. The store was full of people, but all that remained was plus-size women’s clothing, priced at three for $5. Even most of the mannequins had been purchased; rental trucks idled outside as buyers loaded them up with fixtures from the store. Philadelphia’s flagship Macy’s was closing; signs declared it the “final few hours.” I was there with my son, my wife, and my parents. Some guy was riding his bike through the store, which is about when we figured it was OK to let Simon run around. After spending some time entranced by a jewelry case, he found the clothing racks.

The square chrome racks were the kind that fits four rows of clothing, and they were all thrown together in what used to be the shoe section. My son treated it like a maze, moving through the racks and working out how to avoid tripping over their bases. It was a playground in the department store, and he seemed to enjoy it just as much. We all took photos, cheering him on as he worked his way through Wanamaker’s.

That’s what we called it. It hasn’t been Wanamaker’s for 30 years, but Philadelphians are stubborn. Our department store may have been purchased by a New York City company three decades ago, but we liked pretending it was still ours. The store in that space has cycled through a series of names: Hecht’s, Strawbridge’s, Lord & Taylor. It has been a Macy’s since 2006, and it closed Sunday as part of what the company calls a “bold new chapter.” Market Street once had five department stores. Now it has none.

John Wanamaker and Nathan Brown, his brother-in-law, opened their first department store in 1861. He was 22. The store, called Oak Hall, had a gimmick: “One price and goods returnable.” There would be no haggling, and Wanamaker offered a two-week return policy. The young merchant’s store had an auspicious start: 94 hours after opening, the Civil War started. According to William Allen Zulker’s John Wanamaker: King of Merchants, sales on the first day totaled $24.67. But word got around, and business improved. Wanamaker himself started to get a reputation; he opened a second store in 1869 and named that one after himself. By the end of the 1860s, his stores were doing more than $2 million in sales a year. Wanamaker’s is generally considered the first department store, though Zulker writes that Wanamaker “never accepted the honor.”

Brown died in 1868, and Wanamaker leaned into his perfectionism after assuming solo control. “An inner-directed man like John Wanamaker could be hard to get along with in everyday life,” sociologist Tony Campolo wrote in the King of Merchants forward. “He was a man who did not understand the meaning of compromise.” He had a bit of an ego. “Let those who follow me continue to build with the plumb of honor, the level of truth, and the square of integrity, education, courtesy, and mutuality,” read a sign at the store.

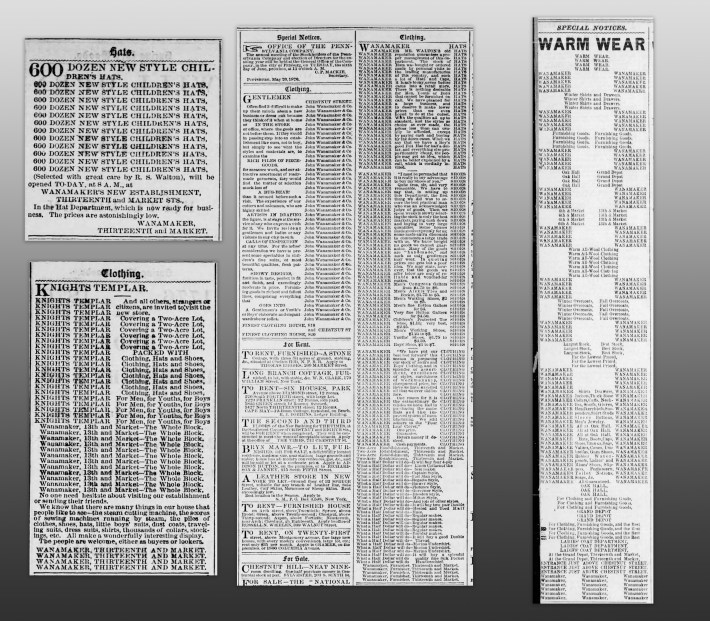

Wanamaker purchased a site at 13th and Market streets in 1875. At the time, 13th Street was on the outskirts of the Center City shopping district and seemed worlds away. Wanamaker had a plan, however. He donated the land for the duration of a religious revival run by Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey. The people of Philadelphia, in making that pilgrimage, realized 13th Street was not really that far. This primed shoppers for the new store, and Wanamaker sealed the deal by peppering newspapers with advertisements that now look like the ramblings of a crackpot—specifically, the ones on the bottles of Dr. Bronner’s.

Surprisingly or not, repeating the name WANAMAKER 111 times in an ad proved successful. The store opened in 1876 with 654 employees. Per Zulker’s book, doormen counted 71,106 visitors on that first day. They would have left impressed. The Times of Philadelphia wrote that a visitor “will likely stare his eyes out as he gazes this Centennial summer on our prosperous clothier’s mammoth house at Thirteenth and Market streets, and should he follow the lead of curiosity and walk in, at the sight of five hundred sale counters, loaded with everything that good tailors make, and rooms on rooms of busy workmen and busy machinery, he will more likely be struck dumb with astonishment.”

The 12-story building, which occupied an entire city block, expanded over time. It was not fully finished until 1911; President Taft presided over its dedication. It had 45 acres of shopping space and 50 elevators. The store was pitched as a modern marvel. “The air in the lower floors of the store is changed every six minutes,” read one advertisement, “being removed by suction as fresh air is admitted.”

The store’s showpiece was the Grand Court, an open atrium stretching beneath a ceiling 150 feet above. There is an enormous pipe organ on one side; in the middle was a 6-foot-6 statue of an eagle with 5,000 bronze feathers. That is the spot where I proposed to my wife.

My department store proposal came on a snowy day in early January of 2018. My wife and I are not ones for pomp and circumstance, and I kept things pretty simple. I did drop down to one knee, which was easier seven years ago, and asked her a question I already knew the answer to. We have a photo in front of the eagle because an employee asked if we wanted her to take one. Somehow my wife and I shared a significant and private moment in the middle of the Macy’s; we committed to spend the rest of our lives together while women tried on shoes a few feet away.

My wife and I were not the only ones to share moments at the eagle. It is a tale mentioned in basically every story about Wanamaker’s: Philadelphians would use the eagle as a meeting point in Center City. The center court also features the aforementioned Wanamaker Organ, the largest fully-functional pipe organ in the world. Since the mid-1950s, one wall of the Grand Court sports a Christmas light show. A walkthrough attraction called Dickens Village, which told the story of A Christmas Carol, was moved into Wanamaker’s from Strawbridge & Clothier when that store shuttered in 2006. A balcony cafe overlooking the court complemented the store’s Crystal Tea Room on the ninth floor; a Wanamaker guidebook said that restaurant could seat 1,400 people. That all of this was so grandiose and outsized and antique somehow never made it feel less like home, or less a part of the city changing and changing away outside.

These shows and meeting places are cherished traditions for many Philadelphians. Another cherished tradition is worrying about the future of those cherished traditions. Macy’s purchased a bankrupt Wanamaker’s in 1995. Since then, basically every story about the store’s future has pondered the fate of these Philadelphia landmarks. TF Cornerstone, a New York developer, plans to convert upper-floor office space into apartments, and says it will keep the organ. The Grand Court was packed one last time Saturday for a final concert. At one point someone played “Fly Eagles Fly.”

Those are the traditions that get written about, for good reason, but they are not the only ones. As we walked through on the last day, my mom talked about going downtown as a kid. People would crowd around the windows to look at new displays. She particularly liked the toy department, where a model train circled the room. My mom and I created our own tradition years later, an annual trip downtown to shop on Black Friday. We saw the light show, and walked through Dickens Village. But my memories of those trips mostly center around picking out clothes, and trying to convince my mom I needed this now instead of waiting to get it on Christmas. When I worked across town I’d often walk through Macy’s after work—there might be a deal in the clearance section.

But those aren’t my main memories, either. My wife and I have a different Wanamaker Building backstory. Ours centers on the movie Mannequin, a 1987 comedy with Andrew McCarthy and Kim Cattrall that was filmed at the store. A while back I bought a DVD of the film, and longtime Dan McQuade readers will not be surprised that I have been able to turn this film into content at three different publications—if this story counts, make it four. For Jezebel I even interviewed Tanya Wolf Ragir, the artist who sculpted mannequins of Cattrall and Meshach Taylor for the film and its sequel. I am deep into Mannequin lore; I cried when Ragir died last year.

I showed the movie to Jan not long after we started dating. It was almost a test. Would she get why I love this bad movie? I mentioned our son at the start of this story, so obviously she did. In some ways, I think she gets it more than I do. When we were watching Mannequin Two: On The Move, the (much worse) sequel, she identified the address of the main character’s house after about 10 minutes of searching.

That is part of how I ended up in the Grand Court, on one knee. We got married two years later; our photographer took shots of us at the eagle then. And yesterday, the two of us posed in front of the eagle with our son. The Grand Court, the organ, the eagle, and everything else in the store are essentially just advertisements. But there’s a reason that all those news stories fret about their future, even beyond Philadelphia’s obsession with its history and lore. They really have become part of the fabric of the city, even if it’s possible the last time anyone met at the eagle was last century.

“I’m going to really miss this place,” my mom said as we followed my son across the store. She hadn’t been there in years. But she worked downtown for her whole career, and Wanamaker’s was the place to shop after work and on lunch breaks. Pawing through clothes racks, even by yourself, can be a great memory. It really was a wonderful place to shop.

My son had his own adventure through the clothes racks on Sunday. He stepped carefully through them, giggling as he discovered a new pathway to explore or a discarded security tag to play with. Eventually he toddled out the other side of the sea of racks, ready to check out the rest of the store. We all continued to walk after him, my dad eventually picking him up and placing him on top of a display case. He needed a rest.

It was great. Wanamaker’s is closed, but we got to make one last beautiful memory there in its final hours.