The moment I had long dreaded finally arrived: the day I’d have to dismantle my childhood. I suppose I should consider myself lucky. It took 43 years to get here, to this spring day in 2025, standing in my nearly empty former bedroom in my mother’s house in Philadelphia, wearing a Mitski T-shirt, ratty yoga pants, and the glasses I only have on when I’m beyond exhausted. And lucky, too, that after the end of a 19-year run at a music writing job that shaped my identity and devoured my time, I was finally able to help my mom move out of the big old house that had become much too much for her.

But I didn’t feel very lucky—not with the encroaching phalanx of contractors, movers, and junk removal guys, and a seven-year-old daughter back in Brooklyn growing increasingly anxious for me to return home to her. I had only two days to pack everything up, including the painstaking task of taking everything off of my bedroom's walls. At work, I had been a master of efficiency and organization, coordinating a team of writers and wrangling the many moving parts of editorial projects into manageable timelines. But standing there in my room, I was at a loss.

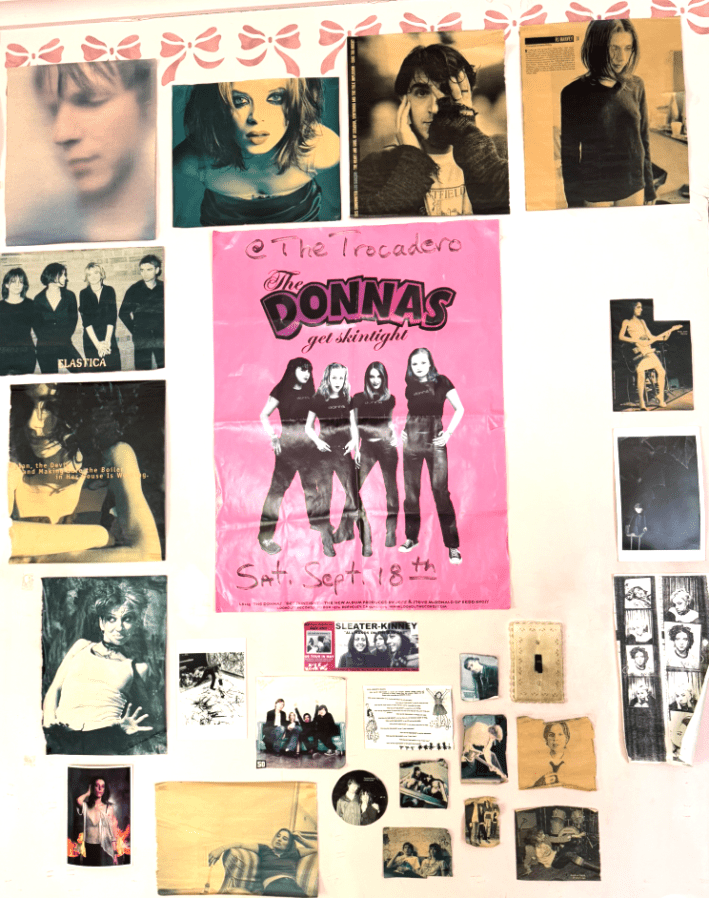

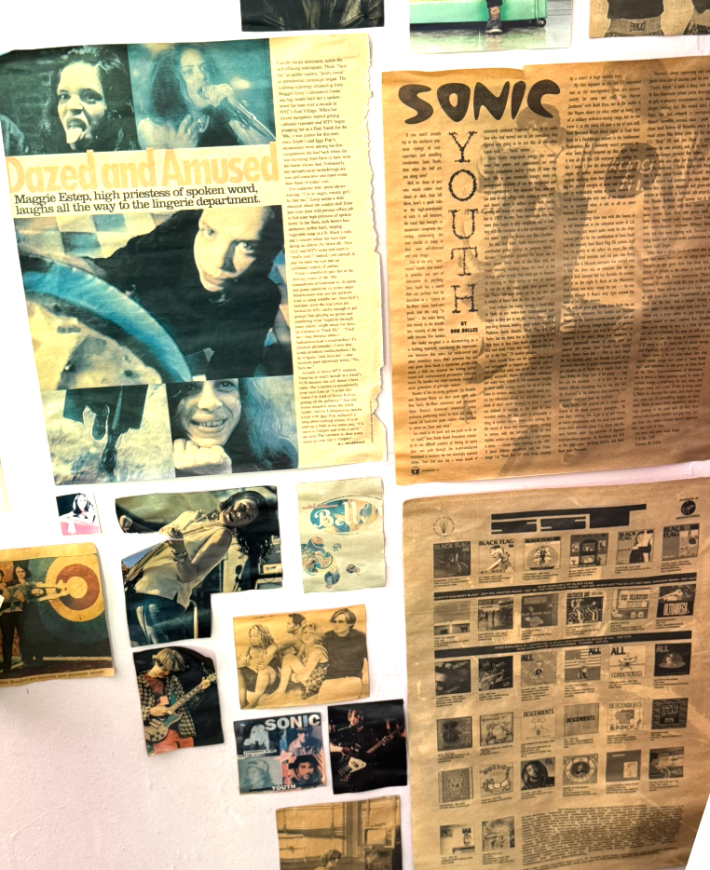

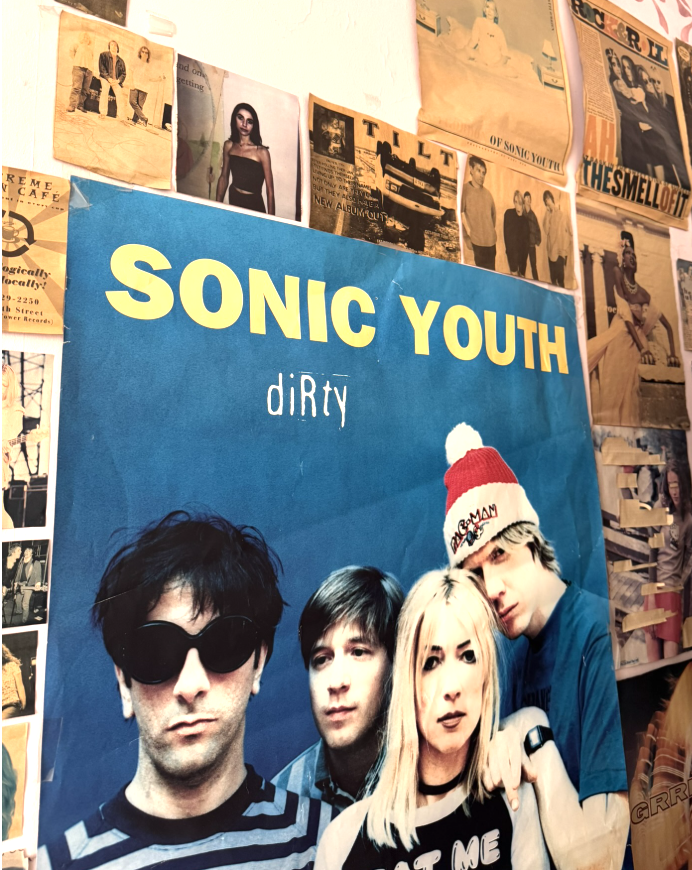

Taped to the walls, floor to ceiling, were hundreds of pictures of ‘90s rock stars, cut from newspapers and magazines over countless hours during my middle and high school years. I’m an only child, and for long stretches of my adolescence, I didn’t have a lot of friends. That left me with plenty of free time to pore over the latest issues of the likes of Rolling Stone, SPIN, Alternative Press, Raygun, Option, Magnet, Tower Records’ Pulse!, Sam Goody’s Request, and CMJ. Sometimes, if an issue seemed particularly image-rich, I would buy two copies: one to keep pristine and treasure, and the other to chop up.

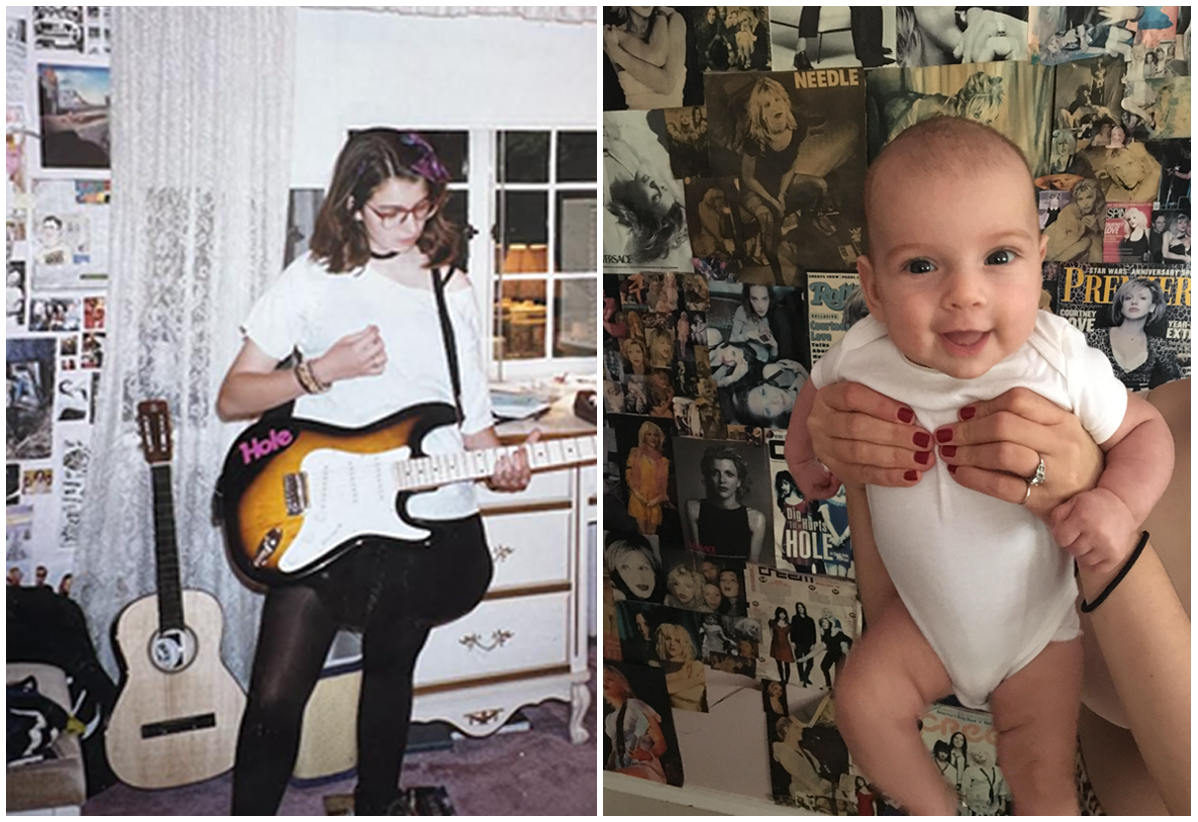

A sane person might have saved a few favorite photos and let the painters scrape off the rest. But I am not a sane person. I needed to take each and every clipping down myself, carefully preserving the ones that didn’t immediately disintegrate on contact. I needed to immerse myself, one last time, in the space where my lifelong obsession with music—and music journalism—was born. I’ve always been more a curator than a creator, relying on other people’s genius to help me make my way through the world. Maybe, standing here surrounded by my youthful idols, I could make peace with who I am now: a recently unemployed, middle-aged mother and wife—everything those images once told me was the opposite of the cool.

I stared at a quote from Björk on a photo from a 1995 issue of Pulse!: “There are certain emotions in your body that not even your best friend can sympathize with, but you will find the right film or the right book, and it will understand you.” Or the right song, of course. Slowly, carefully, I peeled the photo off the wall, marveling that the Scotch tape had managed to hold on for three decades. I placed it gently in a box.

When my mother, stepfather, and I moved into this house in 1988, I was seven years old. And when my mom told me I could decorate my new room however I wanted, I went all in: pale pink paint for the walls with stenciled bows around the top trim, matching wall-to-wall carpeting, and two canopy beds (one for me, one for friend sleepovers). This was girlhood as I knew and loved it: My Little Pony, Barbie, Care Bears, Disney princesses. By 1994, a mere six years later, I was an angsty teenager deep in thrall to grunge, and all that pink started to feel suffocating. So I made it my mission to cover as much of it as I could.

I first became entranced by Courtney Love that spring, in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s death and the release of Hole’s Live Through This. I was 13—the perfect time for disruption. In that messy cusp between childhood and teenagedom, she ripped a wide, deep gash through conventions of feminine comportment. She was loud and wild and beautiful, a paragon of glamorous decay.

The first photo I taped to the wall beside my bed was the cover torn from the April 1994 issue of Option: a softly lit close-up of Courtney looking bored, chin in hand, wearing a black dress with a white Peter Pan collar, signature bright red lipstick, and a necklace spelling out the name BEAN (for her daughter, Frances Bean Cobain). I later added more photos from that issue, then moved on to the May 1994 issue of SPIN, and the June 1994 Rolling Stone issue memorializing Kurt Cobain.

At first, I included some photos of Kurt solo, but I eventually took those down—I wanted the wall to be entirely focused on Courtney. For reasons long lost to my teenage brain, I decided that this wall would contain no space between the images. Every inch would be covered. If the photos didn’t align perfectly, I would cut teeny tiny pictures of Courtney to fill the spaces. Slowly, the collage grew and grew until it covered the entire wall, eventually creeping over the doorframe like kudzu. By the time I stopped adding to it during my freshman year of college, the wallpaper of images measured 12 feet wide and eight feet tall. One photo, clipped from Newsweek, featured a pull quote that stuck with me: “Ever since I was 14, it's like, ‘this year you've just got to shut up.’” Thankfully, she never did.

The photos on the remaining, non-Courtney-fied walls of the room—while slightly more spaced out—still formed a floor-to-ceiling collage of ‘90s alt-rock icons, mostly white women: Kim Gordon, PJ Harvey, Tori Amos, Björk, Kim Deal, Babes in Toyland, L7, Belly, Liz Phair, and on and on. They were the last thing I saw before falling asleep each night, and the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes in the morning. I had built myself a little feminist rock-and-roll cocoon—one where I could quietly, obsessively metamorphose into the grown-up I imagined becoming.

To be clear, that grown-up wasn’t a rock star. After three years of guitar lessons, I came to the conclusion that I hated practicing and had no desire to write songs. I was more captivated by the people behind the bylines—the writers whose articles accompanied the photos taped to my walls. I didn’t want to be in a band, I wanted to be the one writing about them. I dreamed of becoming a cool music journalist in a cool city, covering cool bands for cool magazines.

Incredibly, through some combination of dumb luck, privilege, persistence, and hard work, I actually lived out that dream in various iterations for two decades. But all dreams must end, and so did this one. In January 2024, I was laid off from one of the last good staff jobs in music journalism and watched the institution I helped build slashed down to its barest bones. On the drive home from my final day in the office, boxes in my lap, I found myself in one of those moments that felt ripped straight from a Lifetime movie: My phone rang. It was my mom, telling me she had been in the hospital for three days with heart failure. She was going to be “fine,” she said—she hadn’t wanted to tell me earlier, not with “everything going on.” Typical mom: fiercely independent, committed to doing everything herself. She’d been through worse.

My father died in 1984, when he was 36 and my mom 33. I was three. He had ALS, a neuromuscular disease that progressively destroys every bodily function while leaving the mind fully intact, essentially making a person a prisoner inside their own body. During the two years of his illness, my mom became involved with our local chapter of the ALS Association. After his death, she took over the chapter and became its president. What had been run out of a literal shoebox grew, under her leadership, into a multi-million dollar powerhouse—one of the largest chapters in the country, with a partnership with the Phillies. Before my dad got sick, she’d been a middle school reading teacher. By the time I was a pre-teen, she was overseeing a large staff, hobnobbing with famous donors, and heading off to Washington to work with Congress and the FDA on ALS advocacy.

She got married again in 1986 and divorced my stepdad in 1996, and from then it was just me and her and a cast of cats in the house until I left for college in 1999. After that, it was just her and the cats (now there’s just one). She always said she never wanted to leave, that she wanted to live out her days in the house and its beautiful garden. But after her heart failure in January 2024—followed by open-heart surgery and months of rehabilitation—the house became too much. The stairs were too steep. She needed to move. And with my career suddenly non-existent, I had plenty of time to help her.

Like most kids, I grew up thinking of my mom as an annoying, uncool nag, despite the fact that she drove me to rock concerts, paid for me to take guitar lessons, and let me dye my hair and wear basically whatever I wanted. (She drew the line at L7’s Smell the Magic T-shirt, which … fair.) She also let me spend hours and hours blasting loud music in my room while I cut pictures out of magazines. In retrospect, she was actually a pretty fucking awesome mom.

For most of my life, I would have told you that I was allergic to the kind of generalizing that leads to proclamations like: Being raised by a strong independent woman, surrounded by strong independent women, turned me into a strong independent woman—now raising my own daughter to be the same. Most days, I do not feel particularly strong or independent. But as I’ve gotten older—especially in my 40s—I’ve learned to appreciate what once seemed cringe. To quote the great, underappreciated Bratmobile, “Fuck you too, cool schmool!”

During that frantic two-day stretch, seeped in my youth, I felt like I could finally, fully embrace the influence of the women who both literally and spiritually raised me. My mother—the foundation—gave me space, freedom, and support to immerse myself in music and writing. She modeled how resilience and hard work can get you through the absolute worst shit life can throw at you. So did Courtney Love.

One photo prominently displayed on the Courtney Love Wall, taken from a 1995 issue of Vanity Fair, contains a quote from a Hole fan: “I think she’s been through hell and back. And she’s survived!” But as a mother myself now, I better understand and appreciate the guardrails my mom quietly put in place—disciplinary boundaries that kept me from following Courtney too far down her darker, unstable paths.

Taking down the photos meant seeing what was on the backs of them for the first time in decades. It took all my willpower not to waste precious hours re-reading everything. But there they were: the seeds of my career, the articles that taught me how to write about music. Francesca Lia Block taking the reader deep inside Tori Amos’s fairyland for SPIN in 1996. Ann Powers charting the rise of political feminist rockers in the New York Times in 1993. Emily White reporting on the aftermath of Mia Zapata’s murder in SPIN in 1995. And the articles that taught me how not to write about music: every condescending profile of a female musician that read like the subject was flirting with the male writer, every “Women in Rock” special edition that corralled all the girls together into one issue or feature instead of simply covering them equally year-round.

As I said goodbye to that picture-bedecked room—the womb that birthed my identity as a music writer—I kept thinking about how we’re all just a collection of past selves, a collage of influences taped tightly together over a base coat of pale pink. I am the canopy bed. I am the Courtney Love wall. I am the blank white walls repainted by the contractors, ready for redecoration. (And, no, I am not currently stoned.)

I will always be my mother’s daughter—and a spiritual daughter of my ‘90s alt rock family. But what that means now is very different than what it meant 30 years ago. It means obsessing over the new Chappell Roan video, spending way too much money on Charli XCX tickets, and figuring out who’s going to babysit during the Beyoncé show. It means being a boring middle-aged mom with boring middle-aged problems—navigating life between an aging mother and a sometimes angelic, sometimes bratty daughter.

Concepts like freedom and independence and following your own path mean something very different when half your life is behind you. All I can do now is stay true to the Scotch-taped bedrock underneath it all—whether that meant giving my daughter my last name rather than my husband’s (and marrying a man who was not only cool with that, but encouraged it), or not giving a fuck that all the other moms at school drop-off are skinnier and more made up than I am.

The 48 hours assigned to me passed in a blur of paper and tape and numb fingers. Down came the flyers for so many formative shows of my youth: the magical Lollapalooza ‘95 where I got Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo’s autograph; the 1999 Hole Celebrity Skin tour stop at the Electric Factory, where I waited in line for hours to be in the front row; the Breeders show at the TLA in 1997 that I went to with my high school boyfriend. Down came the collage I made with the lyrics to Sonic Youth’s “Expressway to Yr Skull” (“We’re gonna kill the California girls”) pasted over a page from the Delia’s catalog. Down came the last photo I ever taped up: Destiny’s Child in Newsweek in 2000, with Beyoncé in a Baby Phat tee and Kelly in a New York Dolls (the band, not the strip club) crop top. And down came the Courtney Love Wall. Somehow, one of my daughter’s Peppa Pig stickers had made its way onto a 1992 photo of Courtney, Kurt, and Frances Bean. I hadn’t noticed until that moment.

I didn’t want to listen to music while I worked. Instead, I listened to the Lady Gaga and Ariana Grande episodes of Las Culturistas, trying to inject some levity into the proceedings, interrupted only by calls from the school nurse and my husband about my daughter’s (perhaps psychosomatic) stomach bug. I filled up two cardboard boxes and a plastic bin, then gathered them with the rest of the stuff headed for the storage space in the garage of my mom’s new apartment building. I didn’t have time to go through the bins of intact newspapers and magazines I had been hoarding since the ‘90s in the attic, so those got moved sight unseen. Another nostalgia trip for another time.

The rest of the house was already empty. The next day, the movers and haulers came, and then the contractors got to work. The house was transformed into a shiny, market-ready blank slate by a professional staging company. My old childhood room now features a big white bed with too many throw pillows, a white throw rug, and a shelf full of books about Philadelphia history and interior design. But not for long: As of a few days ago, it’s under contract, with a settlement date set for next week. I wonder what the next family that lives there will be like, what music and trauma will shape them there. Time for the next kid to vomit their personality on the walls, should their parents let them.

Now that my mom is moved and the house is sold, I have plenty of time to figure out what to do with those boxes of photos. Maybe I’ll make my own private ‘90s museum in our Brooklyn apartment. Maybe I’ll make a series of scrapbooks. But for now, I have to go press play on the KPop Demon Hunters soundtrack on the Sonos app. It’s the only thing my daughter will listen to this summer. And I’m going to let her play it as long and as loud as she chooses.