When Chris Christie decided to seek the Republican nomination for President of the United States in 2016, there were some very obvious arguments for and against him. The arguments against were compelling enough that his campaign looks doomed in retrospect. Christie's approval rating in New Jersey was down to 31 percent by the end of 2015, in part because he had been out of the state for all or part of 261 of that year's 365 days, which it turns out is the sort of thing that voters only think they want their governors to do. Some part of it was just Christie being the way that he is, which is extremely high-handed and personally unpleasant. Christie announced his candidacy in June of 2015 and traveled relentlessly as a candidate, with New Jersey taxpayers picking up the tab for his travel and a security detail of state troopers. He refused to reimburse the state on principle; asked on the campaign trail in New Hampshire why he wasn't overseeing the response to severe coastal flooding in the state he governed, Christie said, "I don’t know what you expect me to do, you want me to go down there with a mop?"

But if you leave aside his personality and I guess also his job performance, there are some ways in which Christie's candidacy seemed almost prescient. Christie correctly adduced that the Republican electorate was very eager to line up behind a Big Loud Asshole, and Christie wasn't wrong that his best political skills—talking grandly about leadership; carrying and prosecuting dumb grudges against rivals; standing behind a phalanx of State Police officers and yelling "oh yeah wow what a tough guy" at a schoolteacher—were well suited for the moment. In a sense, it's hard to fault Christie for not being the biggest, loudest asshole in the 2016 GOP candidate field; in almost any other field, he would have been just that. Already something of a joke when his campaign started, Christie stuck around long enough to land some tepid burns on Marco Rubio, but had been reduced to getting stunted on by the New York Times editorial page by the time he finally, inevitably endorsed Donald Trump and dropped out.

In a Republican presidential primary, Christie's most unappealing personal attributes were his strongest selling point; it's not really his fault that he wasn't quite unpleasant enough, and he absolutely was trying his hardest in that particular area. An attribute of Christie's that might have played well had he made it to a general election, in which he would have had to reach voters outside of the "slavering orc" demographic that votes in GOP primaries, is that he can seem convincingly human when discussing some of the things that he actually cares about. Very few of these have anything to do with governance, good or bad, although a tragic family experience with drug addiction led him to be notably more humane in that area than in any other. This is a classic Republican thing: They govern as if everyone else on earth is a repellent moocher wretch who deserves every misery they endure, but they are sometimes willing to reconsider that, narrowly and tentatively, when some similar misery is visited upon themselves, the heroic protagonist of reality.

Anyway, where Christie really shines, or anyway the areas in which he is less overtly repellent, is in talking about his (apparently real) affection for the normal things he really seems to enjoy—Bruce Springsteen, mostly, but also the pro sports teams he cares about. On these topics, Christie really does know his stuff, really does talk about it with some passion, and sounds... well, he still sounds like a blowhard uncle at a wedding reception who starts every sentence with "Listen," but at least like someone that a normal person could manage some elementary small-talk with while waiting for a drink. In the difficult days at the end of his political career, in 2017, Christie even tried out for a co-hosting gig at local sports flagship station WFAN. (In this he was, oddly, following in the footsteps of the accidental former governor of New York, David Paterson, suggesting the region has a surfeit of politicians who ended up governor because it was easier than getting into radio.)

Christie's on-air stint didn't go very well; regular callers got past the producers and called him "a bum" and then he said "look at the big tough guy on the phone," or something like that, for a few hours. A Monmouth University poll pegged his approval in the state at 15 percent by then. Christie didn't get the job.

But he could have done it! Not well, probably, given his temperament and 80 percent disapproval rating and so on, but Chris Christie knows and cares enough about sports to talk about it in a way that is at least recognizably human; he is not better at it than any number of other annoying loudmouths, but he is appreciably of the same species. Christie has made some noise about running for president again of late—he never did find another job he wanted to do—but it's hard to escape the sense that the moment has passed him by in more ways than one.

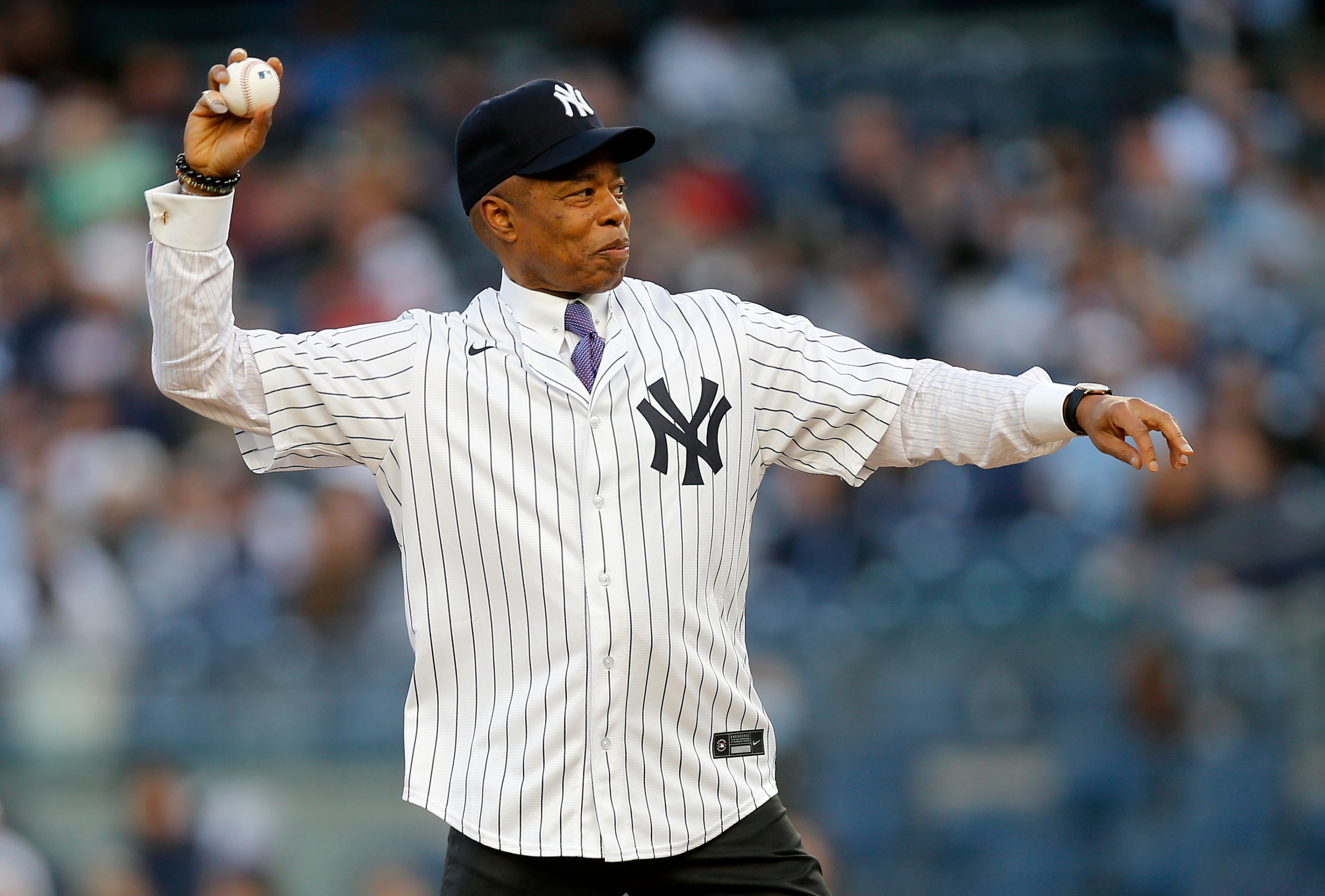

For one thing, the Big Loud Asshole who bigfooted Christie's life's ambition back in 2016 inspired ever greasier and more grandiose weirdos and sociopathic grifters to chase their dreams of political power. Across the country, in races big and small, communities are faced with the decision of whether to elevate obviously daffy and otherwise unemployable goons to high political office. That these people lack the sort of rudimentary political skills that a Christie-grade talent displays—the ability to appear human for a few minutes at a time, or just present as "a type of person who exists in the world"—has not held them back. It certainly has not kept them from reaching high office. And this is how you wind up with Eric Adams, who is the Mayor of New York City, joining the Yankees broadcast on Opening Day and answering very easy are-you-happy-to-be-here questions by telling kids to "put down the Gameboy" and repeatedly bringing up crime and September 11.

The bits to which Adams repeatedly returns are not quite partisan; his catchphrases and obsessions and bewildering personal vibe, which he has imposed on the city with an effectiveness that he hasn't been able to match in any policy aspect, are their own thing. It is not a politician making a canned speech, which is what Christie dinged Rubio for back in 2016; it is not a monstrously vain and venal politician type more or less passing as a normal human being for a few minutes, which is what Christie did during his more effective moments. It's someone who appears to be operating from an entirely different vocabulary of expectations and perceptions, and who transparently believes that he is just killing it.

NYC Mayor Eric Adams loves to come out and root for the home team at "Yankee Park" pic.twitter.com/rvD1ZMdnUX

— Awful Announcing (@awfulannouncing) March 30, 2023

This is just how Adams is. It is tough to say that he represents anything in particular beyond an embodiment of the ongoing trend of communities electing the weirdest and most confident person in that community to increasingly demeaning and impossible governmental roles. This is how Adams does his job, and if no one has ever thought to do it quite this way before—staying up for 22 hours a day, eating exclusively at Midtown restaurants owned and operated by people who have gone to prison for Medicare fraud, talking about undoing bail reform during a Yankees game—it is hard to say that he is doing it wrong by his own standards.

That is, admittedly, a lot easier to assess by other standards. But if Adams's election reflects a bleak new understanding of governance as pure reactive spectacle, the election of relentlessly weird serial fabulist George Santos to a House seat on Long Island almost looks like defensive driving. The trends and broader forces that made his ascent possible are very bad, but Santos is almost certainly doing less damage on a day-to-day basis in the House of Representatives than he would if he had been permitted to keep wandering outer Queens fleecing people out of money intended to pay for veterinary emergencies. It is not "good" that Santos is in Congress, but it could be argued that packing him off to D.C. to do the sort of corny stuff that Members of Congress do is better for the people of his district than leaving him there to do the sort of mid-major felony fraud things that he would otherwise get up to.

Is George Santos good at the congressman stuff? You tell me:

Happy #OpeningDay & let’s go @Mets!! pic.twitter.com/pKQulqpiG9

— Rep. George Santos (@RepSantosNY03) March 30, 2023

Before you answer, remember what he was sent there to do. It is unlikely that voters understood, at the time that they voted for him, that they were doing the equivalent of shooing a very hungry possum out of their kitchen. The incentives that create and elevate a George Santos don't operate at that conscious a level, really. It is important that his politics are cruel, and it is also important that he himself is so relentlessly odd, but this sort of politician exists because people have come to see politics as cynically as politicians do. None of these people—the posh bullies with some latent retail talent; the crystal-vision narcissists; the howlingly overt criminals—will give you anything like what you want. It's not in them to do it; they think that doing so would mean less for them. Watch them bluster and mince in their ridiculous official capacities and their elections can almost start to feel like vengeance. They got what they wanted, and in lieu of any other benefit, the rest of us get to watch them abase themselves doing it.