They started out in Kansas City, only to die before playing a game for want of an arena, and got shipped west in a frantic last-minute move—in all, the proper way for a future NBA champion to begin its existence.

The Denver Nuggets are the second product of the NBA-ABA merger to claim a title (after San Antonio's five), but their history before Monday night was a tape loop of not good enough, fun but not good enough, and occasionally abysmal. Their high-water mark as a franchise was a 112-106 loss to the Nets in the final ABA game ever, and since then they have been known for three things: painting the number 5,280 in every corner of their arenas to make sure opponents knew how far from the earth's core they were, having teams that loved offense and hated defense, and being an early knockout in the playoffs. They were a team you could rely upon to be unreliable in the most important moments, and their best players were shooters, first, last, and always. They were, to give it a name, Carmelo Anthony. And yes, that's probably unfair to Melo.

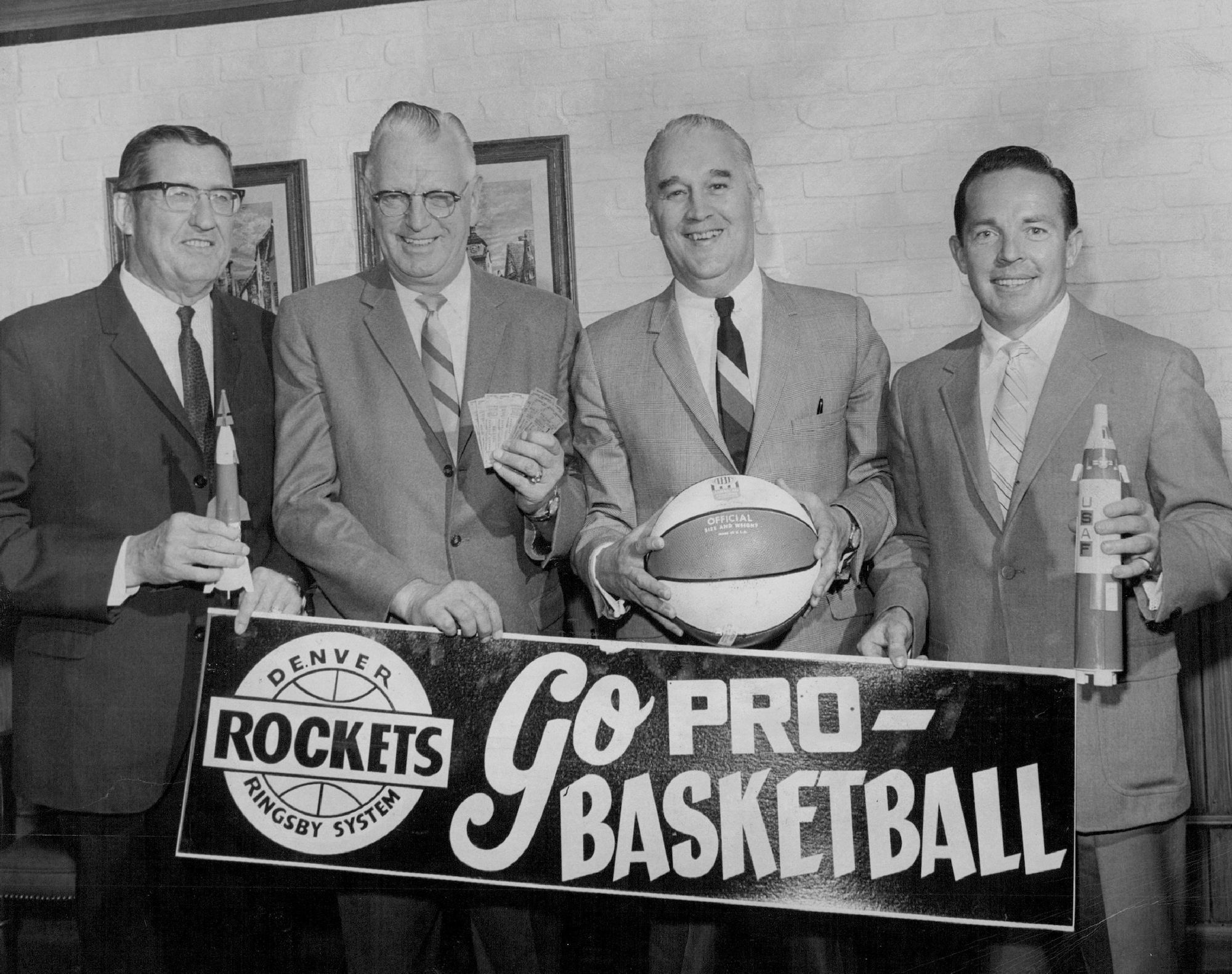

The Nuggets began life in Denver in 1967 as the Larks and then the Rockets, under the care of a trucking magnate named Bill Ringsby who gave money and his product's name (Ringsby Rocket) to the team that eventually gave you Nikola Jokic. Ringsby bailed out the failed Kansas City ownership group and put together teams that lost to the New Orleans Buccaneers, Oakland Oaks, Los Angeles Stars, Texas Chaparrals, Indiana Pacers, San Diego Conquistadors, and a bunch more times to the Pacers. Their greatest feat in nine years was not ending up like the Kentucky Colonels, San Diego Sails, Utah Stars, Virginia Squires, or Spirits Of St. Louis—they survived. They were good enough to be absorbed into the NBA, and even to make the Western Conference Finals in their second year, only to lose to the Seattle SuperSonics to cement their "We Lose To Teams That Don't Exist Anymore" niche.

Indeed, they nearly became one of those teams, lurching toward obliteration in 1974 through a series of bland seasons first caused when their prize rookie, Spencer Haywood, bolted for the NBA. That move, and the ensuing bidding wars over underaged talent, forced the eventual merger of the leagues, and the Rockets, irrelevant in their home town though they were, managed to reinvent themselves just in time to be included with Indiana, New Jersey, and San Antonio in the new NBA. That reinvention included new owners, a new nickname and logo (out: an anthropomorphic dribbling rocket; in: a spread-eagled pickaxe-wielding miner) and a you-don't-have-to-defend-if-you-score-enough-points philosophy driven by ABA veteran Brooklyn wise guys Larry Brown and Doug Moe.

It worked well enough to continue to exist, but the flaw in even the new plan was the same every time. Eventually you don't score enough against the wrong team and you go home. Often, that team was the Los Angeles Lakers, whom the Nuggets swept this year for their first series win ever. But for all the players you would cheerfully pay to watch (Haywood, Anthony, pre-injury and -addiction David Thompson, Alex English, Fat Lever, Dikembe Mutombo, pre-blacklist Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf), you would never consider the Nuggets a team you needed to keep your eye on because they'd be gone in a blink. They filled out a schedule faithfully every year without leaving an impression.

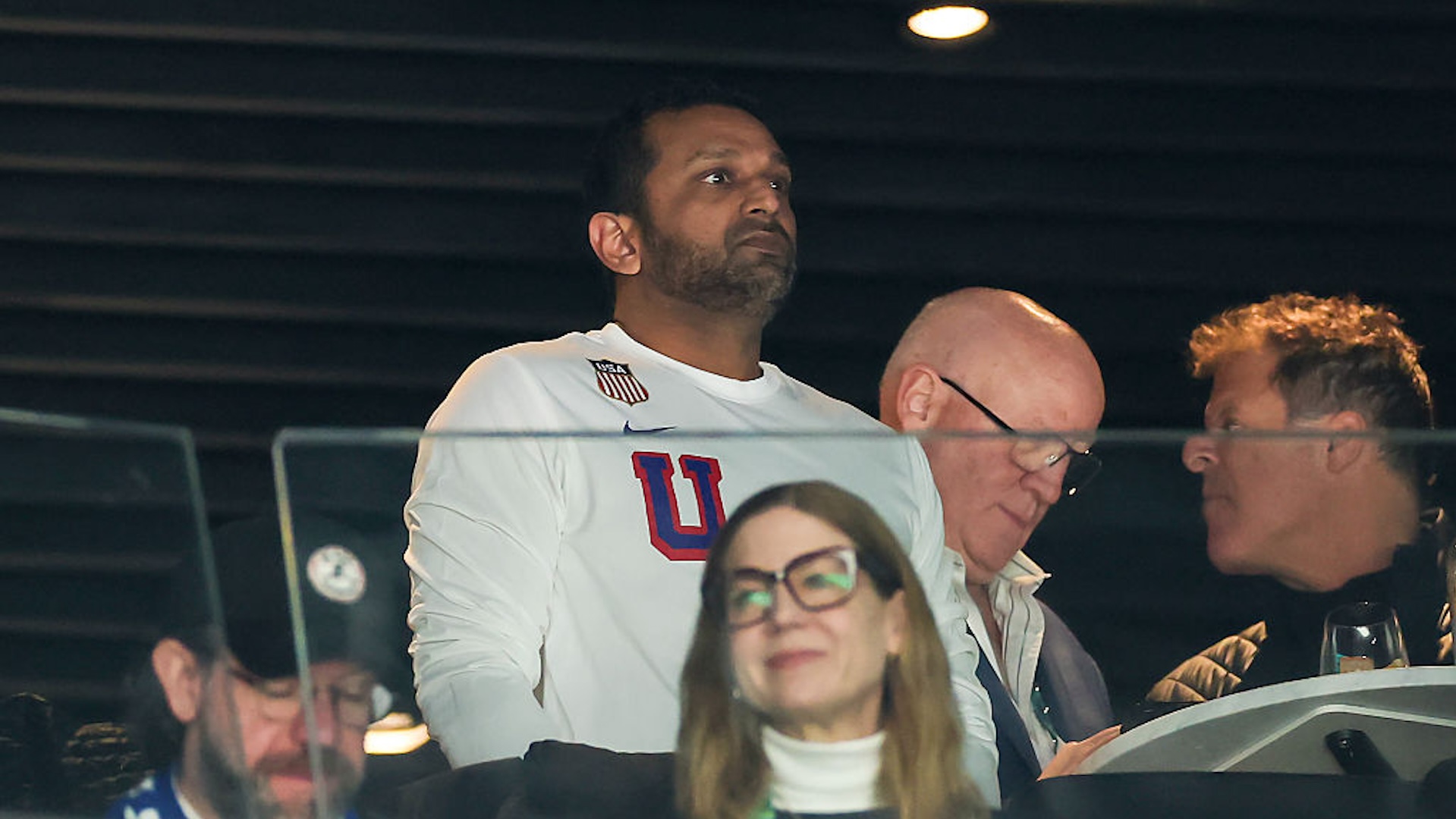

That is, until they tripped over Jokic and previously fired Sacramento Kings coach Michael Malone, and even then it took three years just to make the postseason. And now, in the most hierarchical non-soccer sports league in the world, they are a new champion with all the evaluations of potential dynasty-hood that come with it. Today, they look like the new model of how to play the game, the way the Golden State Warriors were before they became yesterday's news.

Even the carping about the Nuggets' path to glory—beating eight-, seven-, four- and eight-seeds—seems more whiny than analytical. The point is, a year ago, they were what they always seemed to be, a six-seed losing in the first round, and now they are The Thing. That seems almost quaint, and that's saying something when you consider that the first person to hold the championship trophy was Stan Kroenke.