As a general rule, you do not want to know what sportswriters are eating. Assume that it's happening at strange times and in strange ways. Some of this is due to the specific pressures of the job; some of it is just because sportswriters are strange. Sportswriters, on balance, are probably not as strange about food as the people that talk about sports on TV—Jim Nantz orders his toast briquette style; Ian Eagle claims that he has never "ingested" a condiment; Michael Kay once said he had never tried coffee or soup, and didn't eat an egg until he was 62 years old—but sportswriters do not get paid as much, either. Just know that there are a lot of finicky habits in this industry. (Not me, though. I am normal.)

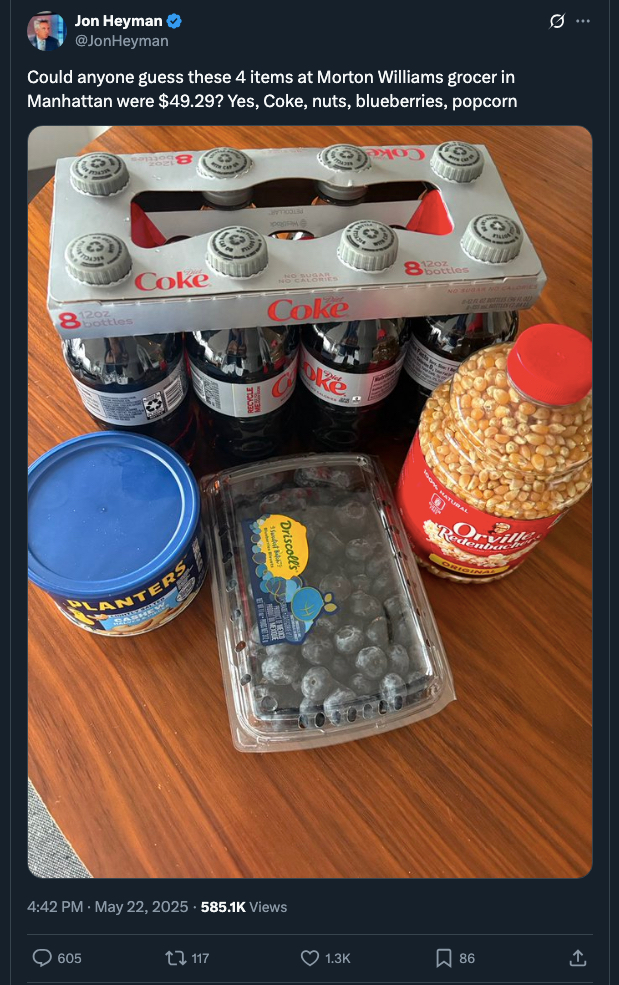

In one sense, the strangest thing about the grocery run that New York Post baseball columnist Jon Heyman posted on Twitter on Thursday is that the order itself is not very strange at all. It's the sort of stuff that a sportswriter might enjoy while writing about sports: a big container of blueberries, popcorn (unpopped), Diet Coke, and cashews. Surely Heyman has peers whose last grocery receipts are far more unsettling. But think about the items above, and how much you would pay for them at the store. Would it be nearly $50? Would you be so upset about how close it is to $50 that you post about it online?

Would you then post a poorly redacted version of your receipt as proof that you were not making this up, and run the risk of revealing that the grocery store you shopped at wasn't all that far from the home of someone with nothing better to do? And whose coworkers know that he does not really have that much else going on at that time? No?

I should mention here that the Morton Williams at which Jon Heyman paid $49.29 for four items is not the closest Morton Williams to where I live. I am familiar with Heyman's preferred branch of the New York City grocery chain—it is not too far from the Trump Plaza, a glum and oddly tarnished-looking co-op tower, the construction of which was one of the projects that led to the 1986 racketeering indictment of Genovese family underboss Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno, and near a cosmetics store that my wife likes. But I do not shop at that Morton Williams, or the other Morton Williams that is much closer to where I live. Until I went to check Heyman's grocery shopping work, I had never been in either.

The thrill of visiting a totally normal supermarket that I'd never visited before was its own reward, in a way, and the presence of a local television news crew in the store—a cameraman panned slowly down and then up shelves of cereal boxes while a reporter watched—was first reassuring, and then less so. It was nice to know that I was not the only person doing journalism in that particular Morton Williams, but what if I got beat on this story by a better-resourced or just more motivated outfit? I was waved past by the cameraman and walked quickly to the back of the store, which felt like the area where they might keep the unpopped popcorn. Chris Isaak's suavely haunted "Wicked Game" was playing over the in-store speakers, which felt about right. I was navigating by feel, here, but I was not going to let a lack of familiarity with Morton Williams keep me from doing what I was there to do.

As we'd discussed it, the idea was that I would go and check Heyman's work, then compare the prices he paid to those at some other grocery stores in the area. We never really got to the part where we figured out why this was a good use of my time, or what broader purpose this mission might serve, and that was another thing I thought about as I tried to figure out where the cashews were. I was able to replicate Heyman's order, and while I had some notes—he paid the highest price in the store for those blueberries, by a lot; a slightly larger container of organic berries located immediately next to it was $13.99, and others were much cheaper—we have already established what and where the baseline is here.

Do I think Jon Heyman might have done better if he'd gotten a bag of the store-brand Best Yet popcorn for $6 less than he paid for the plastic jar of Orville Redenbacher-branded kernels? Sure. But it's also worth underlining here that despite having read his work for years, I do not know Jon Heyman. I would not approach him in the store and say "Jon, big fan—did you notice that there is a fancy brand of 'black popcorn' kernels right there that also costs less than what you're getting?" all while Michael Bolton's cover of "When A Man Loves A Woman" played. ("Wicked Game" had ended by then.)

This was no longer about whether Jon Heyman did the optimal grocery shopping job. It was now about something I'd long wondered, which was how much grocery store prices varied within neighborhoods. It would not be a scientific survey, but more just scratching an itch.

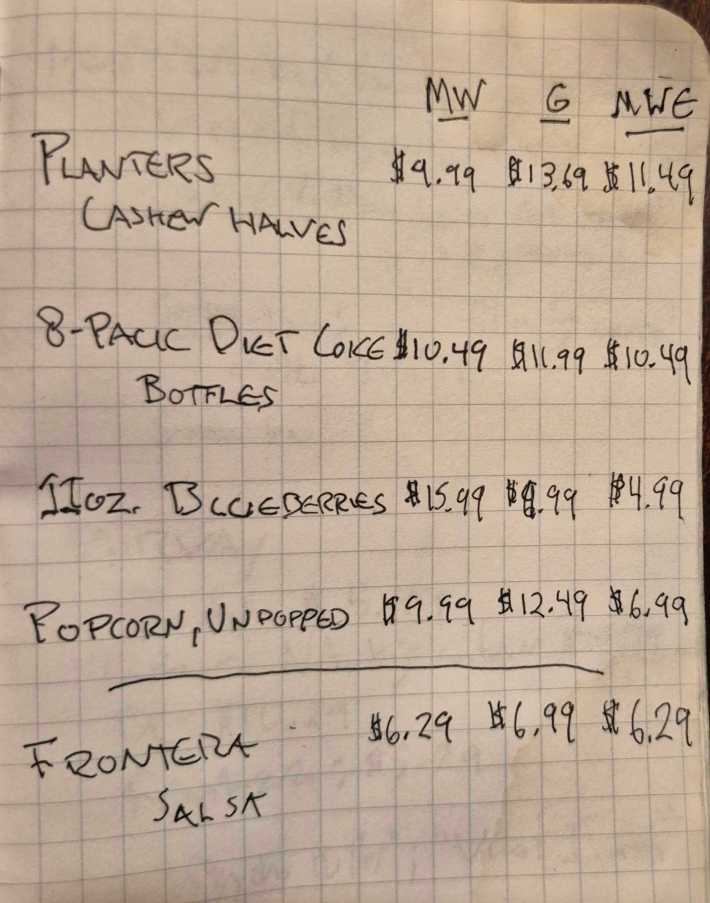

By then I was walking east in the rain, toward the First Avenue outpost of Gristedes, a universally reviled New York City grocery chain owned by the former Republican mayoral candidate and big-time local weirdo John Catsimatidis. It was with this in mind that I started to keep track of another item in my notebook, one that Heyman did not purchase but which I regularly do. The price of a jar of Frontera salsa was fresher in my mind. At Morton Williams, that jar cost $6.29, which I knew was more than what I usually pay for it. At Gristedes, it was $6.99.

The Gristedes I visited was just a quarter-mile east of Heyman's Morton Williams, and much more cheerfully lit and appointed than the location in my neighborhood, which has the look and feel of the grocery store where Jamie Lee Curtis shoots a young Tom Sizemore near the beginning of Kathryn Bigelow's 1990 thriller Blue Steel. It was, as I suspected it would be, much more expensive than Heyman's Morton Williams on every item. Every item, that is, except one: The otherwise reliable John Catsimatidis Worst Price Guarantee failed on the blueberries, which at $9.99 were a cool $6 less than the dry pint Heyman had purchased. Credit to Jon Heyman for not making one of the most obvious mistakes a New Yorker can make, which is to shop at Gristedes.

There was one more itch to scratch, though. The Morton Williams in my neighborhood was more than a mile uptown, and as unfamiliar to me as the one in the grimy shadow of Trump Plaza. Was that enough distance to have any meaningful impact on the price of an eight-pack of Diet Coke? As it turned out, not on the soda. But the prices were otherwise different: the popcorn cost $3 less, the cashews $1.50 more. And the blueberries ... well, I can show you.

Heyman's blueberries were the Driscoll's brand, and these were not. But the difference in price is so notable that I will do the arithmetic for you: This package, which is slightly larger than the one Heyman purchased (his was 11 ounces) is a whopping $11 less. It was, to be fair, also the best price I saw; I looked in at another supermarket closer to my apartment and found the 11-ounce Driscoll package for $5.99.

I won't bore you with the other details of my fourth grocery store visit that evening, beyond noting that I am in fact getting the best price for my salsa of choice. Here is the final accounting:

Jon Heyman paid $48.36 (before tax) for four items that would have cost him $48.16 at a different store slightly farther away, or $33.96 at another branch of the same franchise in an adjacent neighborhood. All of this volatility is the result of the fact that Heyman paid what I now believe with reasonable certainty to be the absolute highest possible price for blueberries. This confirms some suspicions I had going in regarding Gristedes, but also concerning the random nature of grocery prices. It confirms nothing very significant about Jon Heyman, beyond a relatively responsible taste in snacks. If anything, the most remarkable conclusion was the most obvious one—that there is nothing to gain from posting a complaint about how much you just paid for some food. Look where that got us.