The death of Dilbert creator Scott Adams in January at age 68 was followed by obituaries with a predictably wide range in tone. While some were charitable to the late cartoonist, most were less forgiving. Adams’s long leap into infamy on the back of countless racist, sexist, transphobic, and antisemitic statements, and his close association with right-wing politics, cost him dearly while he was still alive, including the eventual cancelation of his comic strip from most of the country’s remaining newspapers. The last decade of Adams’s life was a public and often bizarre downward spiral, culminating in feuds with some of the alt-health quacks who gave him medically unsound advice after his prostate cancer diagnosis. Most of the obits were dedicated to rehashing these late-career follies, only occasionally straying to examinations of his artistic legacy.

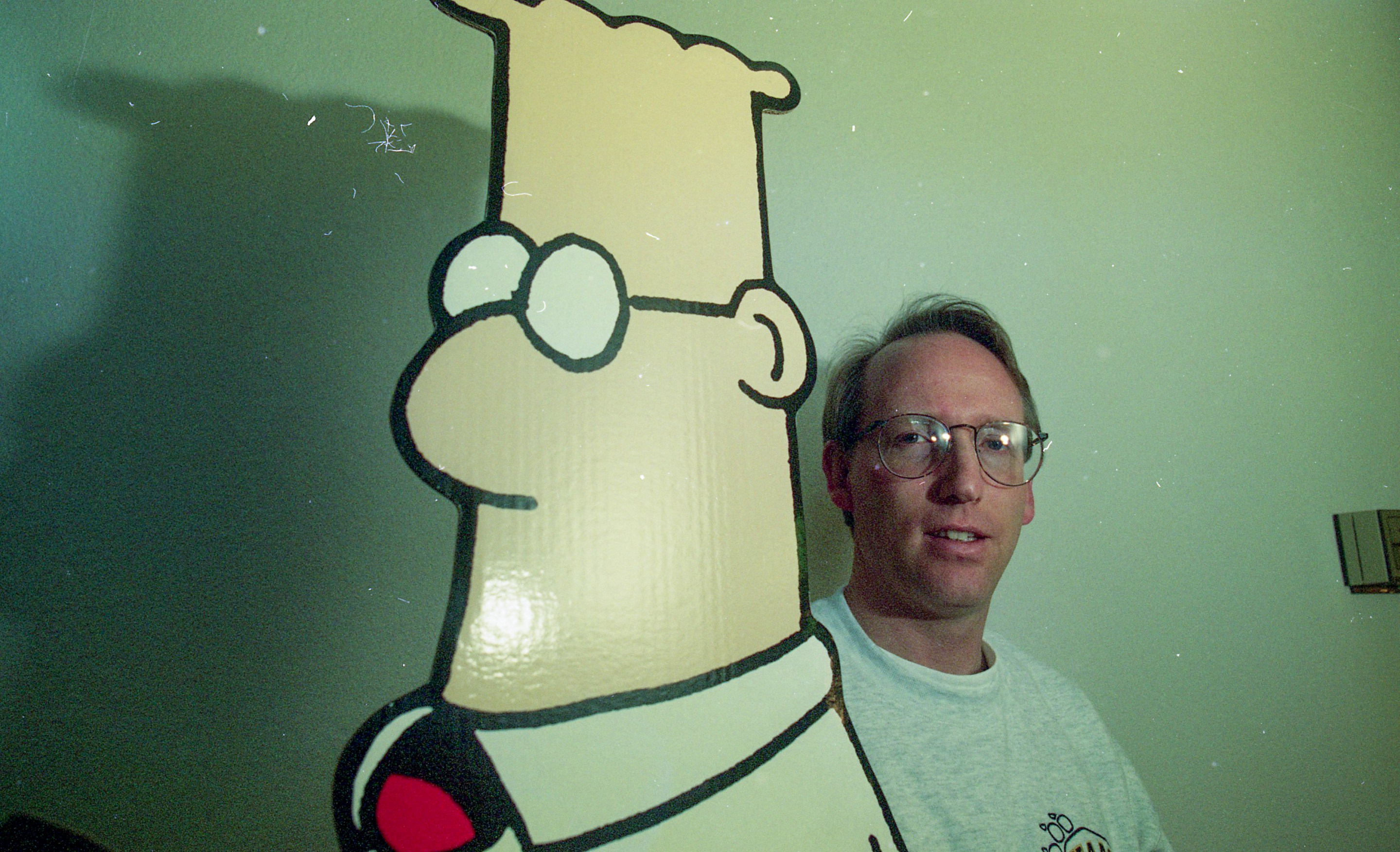

I find myself interested in Adams damaging and/or capitalizing upon his artistic legacy in a different era: at the height of the strip’s popularity. In the late 1990s, Adams undertook tireless efforts to commercialize the Dilbert brand. From the highly successful Office Depot ad campaign to a million coffee mugs to lunchboxes to rubber masks to the ill-fated Dilberito—available in “Mexican” and “Indian” flavors!—Adams was a relentless promoter. Among the franchise detritus, one particularly intriguing tidbit has caught the attention of obscure media aficionados: a supposedly lost, live-action Dilbert sitcom pilot, which Adams wrote and directed for the Fox network.

Numerous articles have identified the pilot as lost media, but are light on details. A ghastly Dogbert animatronic puppet is the only artifact from the pilot that has made it into public view; it was featured on a segment of a local PBS station’s B-movie happy hour, having somehow landed in the collection of a movie prop museum in Florida.

It seems true that no footage of the actual show is to be found on the internet. But in my research, I discovered that the Library of Congress holds a copy in their collection. All hope was not lost. I decided to see if I could finagle my way into viewing it, partly because Adams’s death had left me feeling introspective about the whole Dilbert zeitgeist.

My relationship with Dilbert goes back to my childhood. I grew up in a white-collar household, so Dilbert was ubiquitous. My dad’s career as an engineer definitely contributed to that, but Dilbert was a touchstone well beyond his specific field. Every cube farm was festooned with cut-out Dilbert strips, a sort of language of the semi-oppressed, the universal currency of the office- dweller. Dilbert merch was everywhere, on the shelves of every office supply store in the land and guaranteed to be occupying space somewhere on a desk nearby. As a nerdy kid obsessed with newspaper comics, I had well-thumbed stacks of the collected strips alongside my Far Side and Calvin and Hobbes anthologies.

Reading Dilbert as an adolescent felt like an important and grown-up thing to do, because clearly this was the kind of humor that accomplished, professional adults got their kicks from. Sure, a lot of the jokes about layoffs and the specifics of corporate culture didn’t land for me. But even to a kid, there was real pathos in seeing Dilbert slog through every attempt to break his spirit or degrade his sense of professional ethics. It’s easy to forget because of Adams’s heel turn, but there was real humanity on display in the strip’s heyday. It forged an emotional bond that characterized the best newspaper comics, punching through the glazed apathy of the average reader and created a connection with just three panels. Dilbert was a good man surrounded by evil bosses and lazy cretins. He persisted in trying to do right by his profession, despite all that was arrayed against him. It was hard not to root for him, and at its peak the strip mostly skewered the right targets: moron bosses, slick-tongued marketing lizards, conniving coworkers, and lunch thieves.

Of course, there are some cringeworthy strips in Adams’s back catalog, and when he tried to write about dating or gender politics, he often ran aground. Those strips weren’t vicious, but they didn’t add anything, and largely fell flat with fans. He acknowledged as much in his earlier reflections on the strip, and for a long time avoided non-office topics altogether.

The animated Dilbert television series carried on the wry wit of the comic while adding some depth to the characters. Notably, there were numerous professional writers brought in, including a handful of sitcom veterans. The combo was successful enough to win an Emmy and keep the series running for two seasons and 30 episodes. If not for parent network UPN’s struggles, the show probably could have carried on for a good bit longer. After the animated series went off the air in 2000, the entire Dilbert franchise began to lose cultural prestige. This was concomitant with the decline of regional papers; newspaper comics as a whole lost the cultural cachet they once enjoyed. While it would remain a staple for a particular strain of office drones and tech nerds, Dilbert’s relevancy had clearly faded. I stopped keeping up faithfully with the strips around the time I went off to college, but the few I saw here and there didn’t land with nearly the same punch of the millennium-era stuff. Dilbert had entered its late Simpsons era. Its creator's efforts to take on wokeness were predictably cringeworthy and only landed him in hotter water.

Adams might have faded into genteel near-obscurity if not for his comeback as a social media provocateur, a career second act that almost eclipsed his notoriety as an artist. He was ahead of the curve in predicting Donald Trump’s rise to power, a prescience that garnered him a new cult following. He would spend much of the next decade embroiled in one social media controversy or another, culminating in a disastrous 2023 podcast segment where he advised white Americans to “get the hell away from black people.” By the time newspapers dropped Dilbert en masse shortly thereafter, Adams was more notorious for his social media posting than anything else he’d done in the previous two decades.

I went into my viewing of the live-action Dilbert pilot determined to judge it on its own merits. I wanted to see if I could understand why it was never picked up, despite having been made at the height of the comic strip's cultural power. Maybe the pilot would turn out to be a secret masterpiece, another example of Scott Adams’s supposed unrighteous rejection by the suits he used to so artfully lampoon. And perhaps there would be clues about why Adams veered into reactionary terrain later in his life.

I can fortunately affirm that the pilot isn’t truly lost. The Library of Congress indeed owns a tape copy, which was deposited in 1997 to register the copyright. They’ve even digitized it. On a whim one morning about a week after Adams died, I took a train to the LOC, just across the street from the Supreme Court, picked up my newly minted library card, and asked to see the video. The helpful staff immediately knew what I was asking for. It was obvious that I wasn’t the first to ask for it.

There’s a catch: Since the pilot is still under copyright protection, the digitized version can only be viewed on-site. Because 20th Century Fox (and now by extension Disney) owns the copyright, there really isn’t any prospect of the pilot being legally disseminated any time soon. There’s no way for you to see it except at the Library of Congress itself, in their media repository and viewing room. So I sat down in the '70s-era upholstered chair, slipped on a library-issue pair of headphones, and buckled in.

The video clocks in at just under 26 minutes, and the episode itself spans roughly 20 minutes of that, the obvious target being a half-hour TV runtime. The rest of the reel is given over to test clips and audio-free versions of some scenes, presumably meant for promos. The settings are about what you’d expect: the cubicle-centric office, a conference room, the boss’s corner, and a quick foray into Dilbert’s apartment. All the major characters from the strip are represented, including a few recurring side acts.

The casting is a panoply of workaday TV, film, and stage actors. With few exceptions, they’re all veterans, usually character actors. Tracey Ellis, she of Last of the Mohicans and The Age of Innocence, is the cranky office feminist Alice. Dilbert’s lazy coworker Wally is Tom McGowan, of Frasier and Everybody Loves Raymond fame. Patrick Fabian, long before his Better Call Saul role, plays a jerk salesman from marketing. Dilbert’s evil boss is Fred Applegate, another veteran screen and stage guy who’s had bits on everything from Seinfeld to Stargate SG-1. The late Gregory Itzin appears as the company chairman. Dilbert himself is portrayed by Daniel Jenkins, a Tony nominee with a long list of Broadway and film credits.

The voice of Dogbert is credited to magician Penn Jillette. About that puppet: While not exactly the stuff of nightmares, it’s a pretty artless rush job that doesn’t look much like the strip character, or even like a dog. It moves with the juddering gait of a worn-out pizza parlor animatronic, and mostly has the effect of making an otherwise passable production look cheap.

The cast also includes Tom Virtue (a coworker), Rebecca Chambers (a coworker and potential Dilbert love interest), Julie Hagerty (yes, the Airplane! actress, here as a company client), and Richard Fancy (a manager). Kelsey Berglund, Richard Israel, Susan Isaacs, and Marla Frees round out the credited cast list. In short, it’s a list of real professionals, and no real stars. Most of their performances are serviceable, but by the end of my viewing I could start to understand why the project fell short.

After the pilot’s failure to gain traction with Fox, Adams complained that the actor cast as Dilbert was too handsome for the role. He apparently envisioned a more homely lead character, in keeping with the Dilbert strip persona. Jenkins isn’t exactly Brad Pitt, but he’s not an ugly guy either; I think he would have made a fine Dilbert. He shows good comedic timing in the pilot, despite what he was given to work with. Ditto Fred Applegate, who fills the shoes of the pointy-haired boss with some aplomb. His lines aren’t memorable, but his personality carries the role. The problem with the pilot is that it’s just not very funny.

It opens with a meeting in a conference room where all the main characters are in attendance. In a setup gag, the boss lays off one of Dilbert’s coworkers after his daughter unknowingly volunteers him for a firing during Take Your Child To Work Day. The laid-off coworker then gets in a fight with Wally as he tries to steal his office chair from his cubicle. The humor would be familiar to any Dilbert reader of that era of the strips, but it doesn’t quite translate to the screen; as an extended gag rather than a three-strip setup/punchline, it comes off as more cruel than anything else.

This off-kilter feeling doesn’t get any better. There’s an “A” plotline about a fatal bug in the company’s computer code that Dilbert has to work overtime to solve, but this is repeatedly interrupted by numerous subplots drawn straight from the strips. Dilbert blows up a relationship with a client by telling her about the software bug. He manages to avoid punishment because the marketing guy steals his idea to sell the bug-free version as a software upgrade. (Confusingly, the pointy-haired boss also takes credit for this in another scene.) Then Alice files a sexual harassment complaint against Dilbert for looking too long in her direction. Meanwhile, Dogbert smooth-talks his way into being hired as a high-paid consultant. He advises management to show that Dilbert could not have been staring at Alice because he can’t see without his glasses; Dogbert proves this by throwing a chair at him. Finally, there’s the introduction of Heather, an attractive female coworker that Dilbert awkwardly flirts with under Wally’s encouragement. There are a few laughs to be had, but the whole is much less than the sum of its parts. It feels exactly like what it is: a collection of cartoon strip punchlines, not a coherent episode of television.

If anything in the pilot sticks out as a relic, it’s the Alice subplot. Tracey Ellis as Alice feels like she isn’t having any fun with the role, and the material doesn’t do her any favors. In the strips of that era, Alice was largely written as a frustrated but effective coworker who never receives credit for her contributions. In this portrayal, she’s drawn as a caricature of a professional-class feminist. She files a harassment claim against Dilbert after he looks at her for more than three seconds, which she claims is evidence of leering. She loses her complaint. That the episode ends with Dilbert’s gratification at having successfully flirted with another coworker is clearly meant as a deliberate repudiation of the entire sexual harassment paradigm. In the end, Alice is left looking like an unreasonable, undersexed shrew with an axe to grind—a far cry from the more sympathetic character in the strips.

Beyond that specific qualm, it’s easy to see why the pilot wasn’t picked up. There simply isn’t enough material here to work up into a full-fledged TV show. In the roughly 20-minute runtime, all of the familiar strip punchlines were hit. There’s Wally, the dweeby corporate sponge, always looking to protect his job by doing as little as possible. There’s the pointy-haired boss who steals the credit and kicks consequences downward. The slimy marketing guy promises too much and underdelivers. Dilbert’s hard work goes unrewarded. There’s a layoff, there’s buggy software, consultants that give bad advice, and office feminism run amok. With all of that, what’s left over for Episode 2?

There’s a sharp contrast here with the animated series, in which the writing room took the characters from the strips but developed original, running plot lines that held over multiple episodes. The pilot, on the other hand, features Adams as the sole credited writer. I’ll defend Adams’s talent as a strip writer (up to a point), but he clearly didn’t have the chops to run a show like this on his own.

In fairness, the pilot’s shortcomings highlight a larger problem of adapting comic strips into longer works. The artist has to move beyond the constraints of the newspaper format and articulate a different kind of vision, one a little broader and deeper. This can unlock opportunities for new ideas, but it can also mean compromising the original vision and ceding creative control. Charles Schulz and Jim Davis went down this road and became commercial juggernauts, partly because they were less discriminating in how Snoopy or Garfield might be used. This is also why Bill Watterson famously rejected the idea of turning Calvin and Hobbes into a merchandising machine, even though there was enormous interest in doing so. He valued the integrity of his art and control of his characters above all else, turning down what would have easily been millions of dollars.

Since the conclusion of Calvin and Hobbes in 1995, Watterson has basically vanished from the public eye, while appreciation of his art has only grown. Adams pursued a path closer to the American mainstream, licensing and relentlessly promoting the Dilbert franchise in every conceivable arena. That made Adams a rich man, but it seemingly wasn’t enough to make him happy. He spent his last years indubitably Online, claiming to teach hypnosis to ChatGPT, and generally exhausting whatever goodwill he had earned in his artistic salad days. Maybe Adams could have learned a lesson from his contemporary Watterson, but they were very different men. I hope that the live-action Dilbert pilot, and the broad arc of Adams’s life, tell a cautionary tale about not quitting when you’re ahead.