There are only two pieces of media that have made me wistful for a small-town/suburban childhood I didn't have: A Christmas Story, and Calvin and Hobbes. Before you accuse me of specifically longing for the tract housing of Ohio, if I interrogate this a little further it turns out that what I really wanted was a yard. Because I wanted to shoot a BB gun at imaginary bandits like Ralphie did, and, like Calvin, I wanted to build demented snowmen.

Bill Watterson knew, or at least captured better than anyone, the private derangement of the average 6-year-old boy. Imagination is one thing: Monsters lived under the bed, dinosaurs roamed the Earth, teachers were misshapen alien monsters in disguise, Tracer Bullet charges $50 per day plus expenses. But somewhere beyond those fairly standard fantasy worlds lies the grisly id of the artist, and the snow is his canvas.

Calvin and Hobbes is perfect. It's the perfect comic strip. I don't know any way to describe it better than that. It is earnest and sarcastic, philosophical and silly, violent and serene. It ran for 10 years, and ended at the height of its creativity. Watterson was burnt out; he had had a huge battle with Universal Press Syndicate over merchandising, which he didn't want, and after winning total creative control, he became reclusive, moving to the desert and turning down all media appearances. He wanted the strip to speak for itself, and when it had said what it had to say, it got out before it got old.

I didn't know any of this at the time. I just knew it was very funny and relatable, and I had several of the book collections, stored in a crate next to my bed along with the Garfield and The Far Side books I also treasured. One of those I outgrew, the other I still love for its absurdity, but only Calvin and Hobbes got better as I got older and came to identify increasingly more with Calvin's parents than with Calvin. Time hasn't eroded its appeal for me so much as it has exposed its heart.

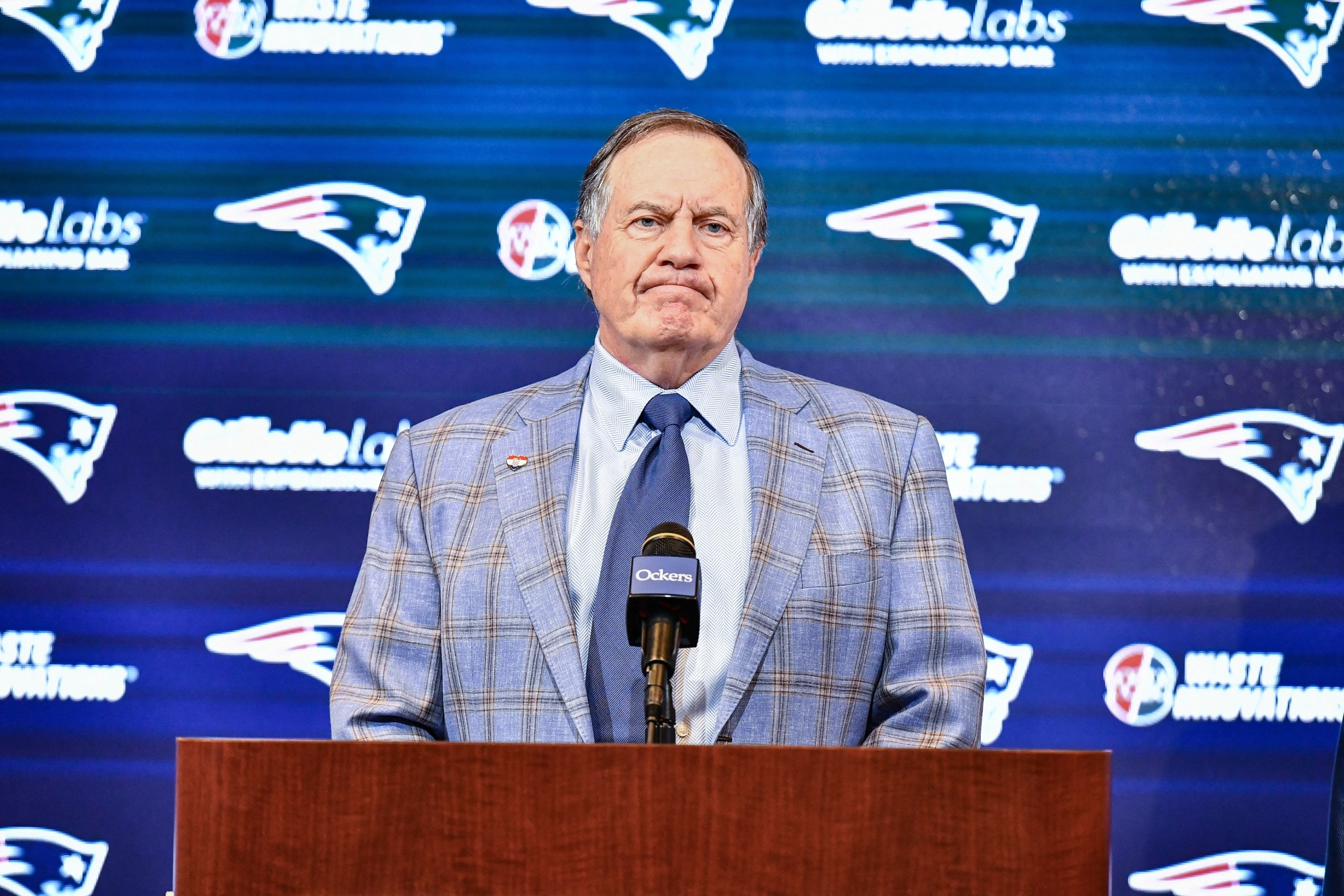

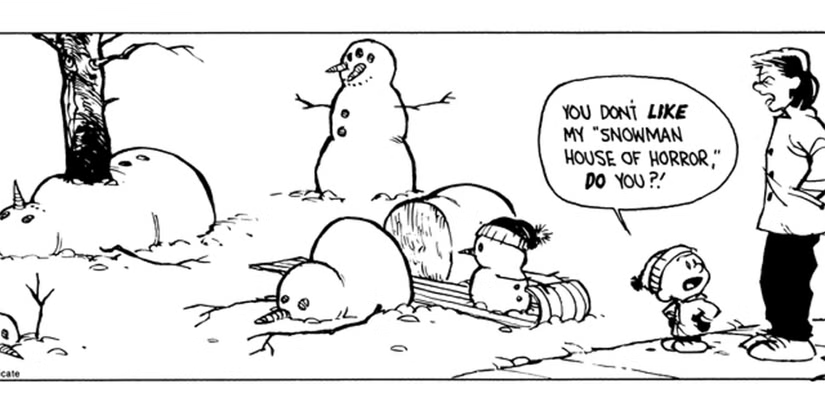

But: the snowmen. That running gag wasn't about heart, or so I didn't think as a kid. It was about what a young boy finds funny, and what a young boy finds funny is cartoonish violence, and what a young boy finds strange is that everyone doesn't find it as funny as he does.

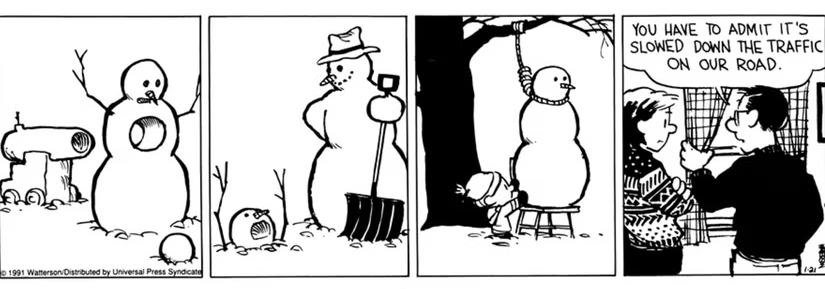

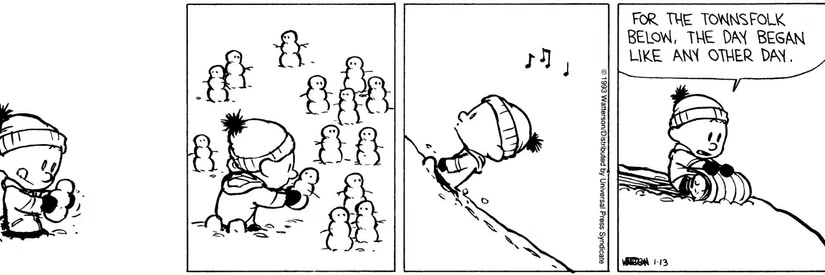

"Misunderstood" is the standard operating state of a child. "Inscrutable" is the face they show the world. Somewhere between lies the truth, that adult and child may as well be two different species for their mutual incomprehensibility. Watterson's magic was, I think, as straightforward as being able to remember. Most of us forget, but we retain some epigenetic traces of the wonder and the confusion of living in a world not made for us, and Watterson's work is able to activate those sleeper cells. There is something atavistic in the joy I still recognize in the concept of taking a kaiju-scale death sled through a horde of tiny snowmen:

The snowmen were how Calvin expressed himself: his cravings for destruction, his fascination with anatomy, his frustration with his creations not being valued as much as he believed they deserved. His medium was the endlessly malleable slush of his imagination. (He was, from one angle, an artist with complete creative control, toiling in an industry that preferred marketable conformity to auteurism. Watterson, you scamp.)

Calvin was unrealistically precocious, but not because he was an author's mouthpiece. The fun of the strip was from the delta between his intelligence and his worldliness. He had an only slightly exaggerated 6-year-old's sense of how the world should be, but based upon first principles—and a child's selfishness—rather than gathered directly by living in it. "The thing that I really enjoy about him is that he has no sense of restraint, he doesn't have the experience yet to know the things that you shouldn't do," Watterson said, back before he swore off media appearances. And, in another interview: "The socialization that we all go through to become adults teaches you not to say certain things because you later suffer the consequences. Calvin doesn't know that rule of thumb yet."

In his world of snowmen, however, Calvin was god. He made the rules. He dealt out punishments. He reveled in making others perform for his amusement, because in his life, he was the servile homunculus forever at the mercy of authority figures operating under mores he didn't understand and which thus felt arbitrary.

In Calvin's world, Calvin's subjects understood and demanded justice, which coincidentally looked a lot like freedom:

As an adult, I find Bill Watterson an inspiration—an actual role model, which I didn't really have or think much about as a child. Mostly for his refusal to compromise his principles, which would have made him a very, very rich man, because he took more pleasure in the creating, and in the freedom to create, than he would have from the money. If we must lose so much of what made us tick as children when we collide with the real world, we needn't lose that base idealism itself.

I built a snowman once, just once. At my grandparents' house in the suburbs, where they had a lawn just like the ones I'd seen in the newspaper. It was harder than I'd imagined. Also it was cold and damp and miserable out there. I settled for something closer to an ice cream cone than a life-sized representation of a human form. He was probably five inches tall, three diminishing, roughly rounded snowballs atop each other, and I named him "Ugly." Real life never quite lives up to your imagination. That's only a tragedy if you stop thinking of your inner life as real, too.