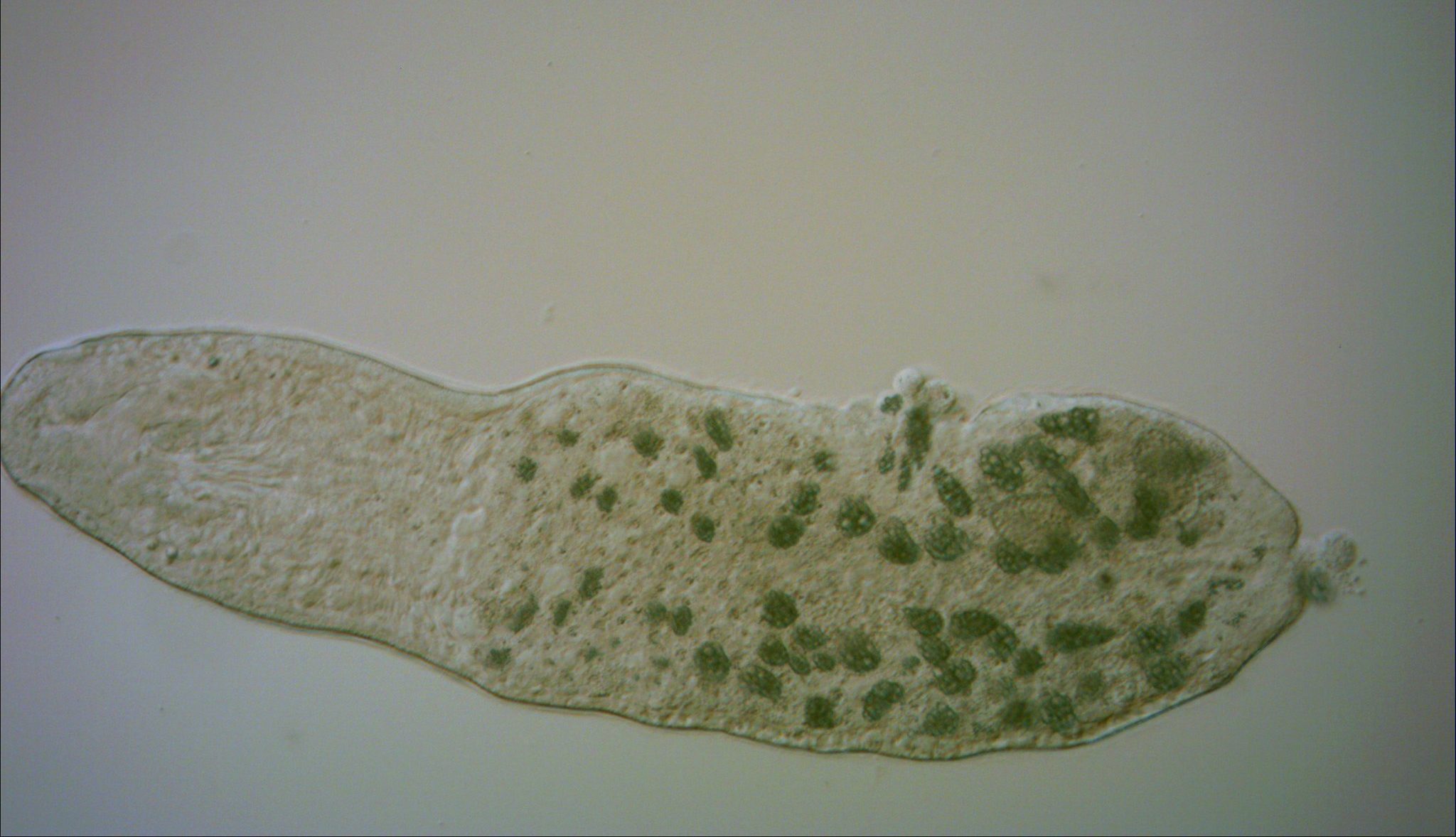

The freshwater flatworm Stenostomum brevipharyngium is, by all accounts, a simple fellow. The worm is small and entirely soft. It has no eyes, only sensory pits that control balance and orientation. This simplicity makes it easy for S. brevipharyngium to make more of itself in every way possible. The flatworm can regenerate major parts of its body, such as sensory organs and musculature, as well as make more worms via asexual reproduction.

The most famous form of asexual reproduction might be budding, in which a new organism emerges from a "bud" on a parent like a new polyp emerging from a coral. But the way S. brevipharyngium sees it—which here is a turn of phrase, as the worms have no eyes—budding is for squares. These flatworms reproduce through a process called paratomy, in which an individual forms new organs inside their original body before splitting into two. This happens through a different molecular process than mere regeneration, in which a split worm regrows a head or a tail. In paratomy, the worm must obey its existing body axis—understanding which end of the original worm is the head and which is the tail so they can put their new tail and new head in the right places.

Katarzyna Tratkiewicz and Ludwik Gąsiorowski, scientists from the University of Warsaw in Poland, were keeping a colony of S. brevipharyngium in the lab when they noticed something strange in one of their cultures. Most of the hundreds of worms in the petri dish were reproducing normally, splitting themselves into two complete worms. But there were also a few double-headed worms—worms with heads on both ends of their body, whose emergence Tratkiewicz and Gąsiorowski described in a new paper in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

This particular petri dish of worms looked like any other. The worms ate the same paramecium prey. They were kept under the same conditions, room-temperature and in the dark. Their dish was cleaned like any other. And yet this dish kept delivering double-headed worms, a few at a time. Tratkiewicz and Gąsiorowski screened their other petri dishes for two-headed flatworms, but found none. When they tried propagating this culture into a new dish, the double-headed worms appeared fewer and fewer times before disappearing entirely. And just like that, the fad was over. "The entire outbreak of the double-head worms lasted altogether for ca. 2 months," the researchers wrote.

A paper from 2017 showed that running an electrical current through the planarian Dugesia japonica could flip the worm's head-to-tail axis, resulting in reversed worms, as well as as worms with two heads or two tails. But this was the first time the double-headed worms had appeared spontaneously. When the researchers cut the double-headed worms into three pieces with an eyelash, the worm fragment with a tail regenerated a head and the fragment with a head regenerated a tail, as would be expected. But the worm fragment in the middle regenerated a tail on the end of their body that once pointed to its head—effectively reversing the axis of its body.

Questions swirled around the rapid appearance and disappearance of the double-headed worms. Scientists like Tratkiewicz and Gąsiorowski wanted to understand, first and foremost, why the double heads formed and by what molecular mechanisms. Bloggers like me wanted to understand, first and foremost, which head would be in charge. Fortunately, Defector was able to secure a brief interview with both heads of S. brevipharyngium, to talk about living, laughing, and loving as a two-headed worm.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Thanks so much for sitting down with us during what must be an overwhelming time for you amidst the publication of your new paper. How has your day been?

Head 1: Fine.

Head 2: It stinks!

Oh, I'm sorry to hear that, Head 2. Can you share more?

Head 2: Firstly, and for the record, I would like to state that I resent this designation of "Head 2." Is there something about me or my head that is giving secondary? Do I come across as subordinate, or somehow lesser than a "regular" head? I am a fully developed head in my own right, with the closest thing us flatworms have to a brain. I am nobody's afterthought! I am no one's Plan B!

Head 1: No one is saying that.

Head 2: Easy for you to say, you're Head 1!

It seems like I've touched a nerve.

Head 2: What a typically human thing to say. We flatworms refer to them as sensory pits, thank you very much.

I apologize, I still have a lot to learn about flatworms.

Head 2: Tell me something I don't know, bozo!

I'd like to get back on track. Can you tell me a little about how you two go about your day? For example, how do you decide in which direction to wriggle?

Head 1: We spend a lot of time ... deciding, which looks like us both wriggling in opposite directions and going nowhere.

Head 2: We'd move a lot faster if Head 1 would just let me navigate. It's a hectic world here in this petri dish, and you've got to bob and weave to avoid bumping into one of the hundreds of other idiots swimming around here. But I've got places to be, worms to see, and a goddamn life to live, and I don't much fancy wasting my time figuring out the perfect direction in which to wriggle. We live in a freaking petri dish! There are no discernible landmarks, structures, or anything you could even charitably call a destination. Our entire world is a third space. But I'd like to see as much of it as I can before I split off into some new worm.

Have you ever seen the 1998 animated television show CatDog?

Head 1: We are collectively about a month old, so no, we have not seen CatDog.

OK, well it was this short-lived and vaguely disturbing children's television show following the hijinks of a creature named CatDog, who is an orange animal with the head of a cat on one end and the head of a dog on the other.

Head 2: And how'd the dog feel about that name, huh? Bet they weren't too pleased! But a show like DogCat, now that's a show I'd watch.

I felt like CatDog might be a good parallel for some of the challenges you navigate in life. For example, CatDog would often move around with one head running ahead and the other side being dragged along. Does this resonate with your experience?

Head 2: Absolutely not, we would never stoop to something like that.

Head 1: Yes.

How would you describe your relationship?

Head 1: Well—

Head 2: What is that?

Head 1: What is happening?

Head 2: It feels like something is slicing us apart! Our bodies are separating, I can feel it in my sensory pits!

Head 1: Oh god, are my wishes finally coming true? Will I finally have a tail of my own?

Head 3: Ahhhh!

Head 2: Who the fuck is this guy?

Head 1: Watch your language!

Head 3: Ahhhh! Who are you? Who am I?

Hello there!

Head 3: Who the fuck is that guy?

Head 2: Ignore them. Well boys, it looks like I'm my own worm now. I've got a head of my own, a tail to match, and a whole wide world of growth medium to explore. Nice knowing you, Head 1, and congratulations on your new friend. I'm outta here!

Head 1: Looks like you're stuck with me, Head 2.

Head 3: Who are you calling Head 2?