The first overtime game in NFL history was a stunt. For three summers in the 1950s, the New York Giants spent training camp in Salem, Oregon. In 1955, they were slated to play a preseason game in Portland on August 28. Harry Glickman, then the president of Oregon Sports Attractions and later the founder of the Portland Trail Blazers, was looking for a way to get a good crowd for a preseason football game. He convinced the Rams, Giants, and NFL commissioner Bert Bell to let him try out two new innovations: The field would be numbered from 0 to 100 yards, and the teams would play a sudden death overtime if the game ended up tied after 60 minutes.

The Capital Journal, Salem’s newspaper, was more excited about the former: “The change in numbering of sideline markers is expected to prove a great convenience for the press and fans, since it will enable them to compute the distance on long gaining plays, punts, and kickoffs much easier.” Was this actually any easier? To me it seems more confusing. Who computes the distance on a kickoff in the stands anyway? Because that rule didn’t have any staying power, we don't need to worry about it. The OT rule was a one-time thing, too, although that one would come back eventually. I don’t know if it juiced attendance—the number was listed at 22,222 for the game at Multnomah Stadium, a number that is, uh, surely accurate—but what were the odds the game would end tied, anyway? Glickman had an answer postgame: “I didn’t think there was a chance in a million it would be used.”

Good thing he didn’t make a bet. The Rams and Giants ended the game tied at 17. Ref Ross Bowen talked to Rams owner Dan Reeves and Giants GM Wellington Mara to confirm it, and the first overtime began. It did not take long. Here’s how The Capital Journal’s A.C. Jones described it: “Apparently getting stronger all the time, the Los Angeles corps of gridders took the overtime kickoff on the goal line and in eight plays carried out the victory requirements—the first to score in the extra session.” Tank Younger scored the winning TD on a 2-yard run; Norm Van Brocklin was the Rams quarterback. Just over three minutes elapsed in the extra session all told. He was not used in the OT, but a man named Thurlow “Tad” Weed was the kicker for Los Angeles; in the 1970s he invented a giant tennis racquet.

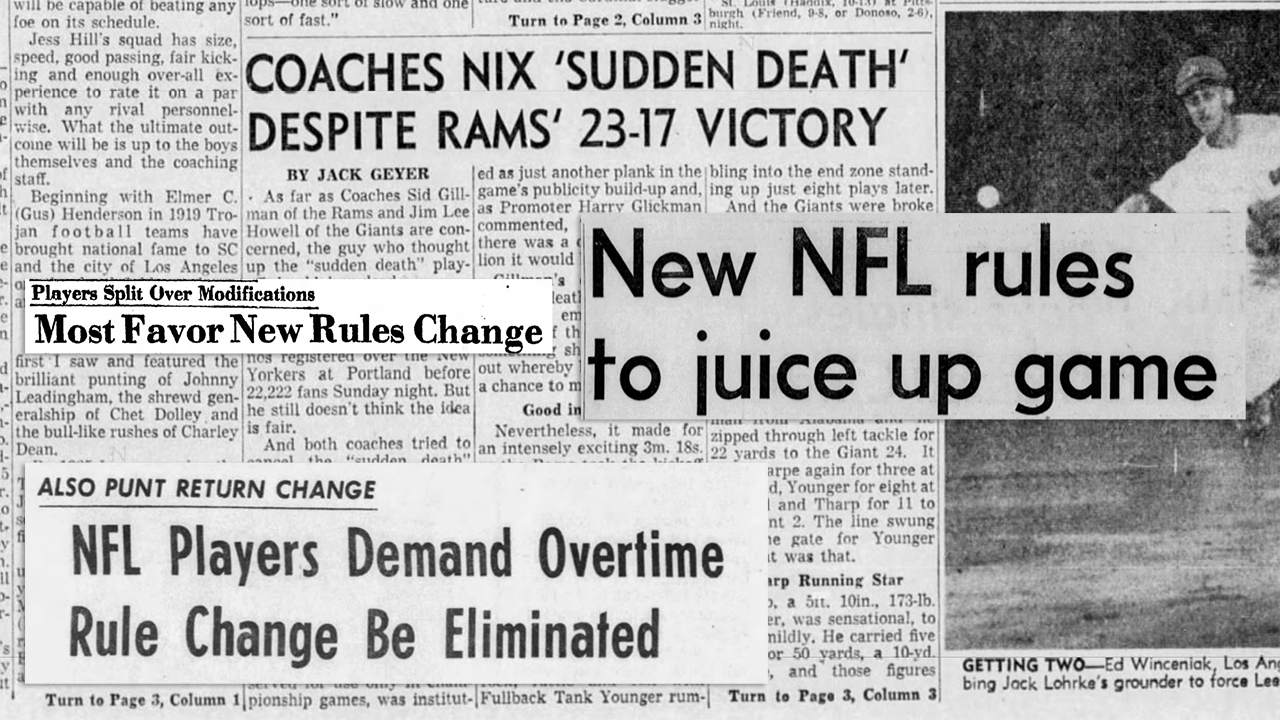

No one really liked OT all that much. “Flip of Coin Gives Winners Chance,” the Journal headline read. Both coaches, the Rams’ Sid Gillman and the Giants’ Jim Lee Howell, had actually tried to stop the OT from taking place when the game ended tied. They both hated the idea of a “sudden death” overtime in which only one team might get the chance to possess the ball. “The Giants were broke without ever getting their hands on the dice,” The Los Angeles Times’ Jack Geyer wrote. Even though his team won, Gillman thought any football overtime should let both teams possess the ball. The players, per Glickman, were split on the issue: The Rams liked it, but the Giants thought it was “a letdown and that players would find it hard to get used to the idea of playing past the final gun.”

It has been almost 67 years since that game, and the arguments about overtime remain pretty much the same. On Sunday the Bills and Chiefs played an incredibly thrilling game where the teams combined to score three touchdowns and a field goal in the final two minutes of regulation. In overtime, the Chiefs won the coin toss. Just as the Rams did in the first-ever OT game, it took Kansas City eight plays to score the winning touchdown—though it took Pat Mahomes Jr. and his teammates about a minute longer. No word if KC kicker Harrison Butker has any plans for a giant polo mallet or something. Who knows what the future holds.

The overtime rules have always been unfair, which is a big part of what people have always disliked about them. The rule changes that have led to more offense in the game have only made it more unfair. When it’s easier to score points, the team that gets the ball first in overtime generally wins. But the NFL has only ever done sudden-death overtime. The first OT game that meant something was the 1958 NFL Championship, known as The Greatest Game Ever Played. “We really didn't know what to do,” Colts receiver Raymond Berry said. “We’d never played it. Nobody had ever played it. Nobody really knew what came next.” The Giants won the overtime coin toss but couldn’t move the ball; Baltimore scored on their ensuing possession on Alan Ameche’s 1-yard TD plunge. Former NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle credited the game, and its entertaining overtime conclusion, for the NFL's rise in popularity.

It was another OT game that helped the then-fledgling American Football League, the NFL’s rival in the 1960s. The Dallas Texans, the organization that is now the Kansas City Chiefs, defeated the Houston Oilers, 20-17, in double overtime in the 1962 AFL Championship Game. There was a big snowstorm on the East Coast, so TV viewership was high in the parts of the country that NFL and TV executives cared about most. There was an infamous blooper before overtime. The Texans actually won the toss and attempted to defer in order to have the strong wind at their back. But the Texans’ Abner Haynes said “we’ll kick to the clock” instead of which direction he wanted, and so the Oilers got both the ball and the wind at their back. No matter. Offenses stalled and the Texans won on a field goal in the second OT period. Still, it was proof that, ah, usually you would like the ball at the start of overtime.

It wasn’t until 1974 that the NFL adopted OT for regular-season games. The original overtime rule was itself part of an attempt to increase scoring; reporters at the time said it was done in part to head off the World Football League, a new league that would begin play later that year. Rozelle said it was in response to criticism of that year’s Super Bowl, where the Dolphins beat the Vikings 24-7. “The clubs felt frustration,” the NFL commissioner said. “They wanted to see more offense. They have been sensitive to the criticism of the Super Bowl from both the media and the public.”

The NFL proposed seven changes in April 1974, in response to a game that had become dominated by defenses. Kickoffs were moved from the 40 to the 35. Missed field goals would return to the line of scrimmage instead of the 20. Goalposts were moved back to the end line instead of the goal line. Offensive holding was reduced to a 10-yard penalty instead of 15. Defenders could no longer hit receivers as much as they wanted. Crackback and other blocks were restricted. And the league instituted that 15-minute sudden death overtime. (The WFL’s planned overtime notably was not sudden death; called a “fifth quarter,” there would be two seven-and-a-half minute overtime quarters with two kickoffs. The WFL was otherwise angry about the NFL’s rule changes. “It looks like they went right down the line and copied our rulebook,” said Tom Origer, owner of the league’s Chicago Fire.)

Once again, coaches and players hated the rule changes. Don Shula was happy that Mercury Morris could return kicks more easily, but voted against the rules anyway: “When you have been as successful as we have in Miami, you naturally are against all changes.” Norm Van Brocklin, then coach of the Falcons, said: “My personal feeling is that these changes are a reaction to the media.” The Giants were worried they’d have to schedule games earlier, as there weren’t lights at the Yale Bowl. (They played there in 1973 and 1974 after Yankee Stadium kicked them out.) A wire report in the Los Angeles Times ended like this: “The reaction of Philadelphia Eagles coach Mike McCormack was a screeching, ‘Ech!’”

The players hated overtime especially, saying they deserved more pay for longer games. “I think it’s stupid,” NFLPA executive director Ed Garvey said of overtime. “It exposes players to more injuries since, after four quarters, they are exhausted and more likely to get hurt.” Browns middle linebacker Bob Babich said players should get “time-and-a-half pay for overtime.” He was “half-joking,” a report said.

The labor strife that year was no joke. Players made demands, including the elimination of overtime. They actually made 90 demands in sets of 57 and 33 before the 1974 season; personally, I would’ve done it 5-10 demands at a time, but more power to ’em. Players went on strike in July and the NFL fielded replacement players, mostly rookies, for preseason games. They broke the strike, and players returned in August without a contract, content to let their arguments play out in the courts. The players’ main concern was the Rozelle Rule, a non-bargained rule that a judge invalidated two years later. That rule limited free agency by allowing the league to award compensation to teams that lost free agents, which obviously depressed salaries. The players and owners reached a new agreement in 1977.

Two crucial groups did like the new rules, though: Sportswriters and fans. NFL overtime was here to stay. It would later become tradition that some players did not know there were ties in the NFL. At the start, players didn’t even know there was overtime. Glen Bonner, a Chargers replacement player, said after the very first preseason OT game that he didn’t realize he was going to get a chance to catch the first game-winning pass under the new rule: “I was surprised to hear about it. The first I knew about it was when they said over the loud speaker near the end of the game that if nobody scored there would be sudden death and the first team to score wins the game.” Jesse Freitas threw the first OT TD pass, an 18-yarder, in the Chargers’ 20-14 win over the Jets. The Chargers got the ball first but missed a 37-yard field goal; they’d get the ball back for the winning drive on an interception on the next possession. The next week, there were three preseason overtime games, including one where the Eagles drove to the Pittsburgh 38 and punted into the end zone, then lost the game on the ensuing Steelers’ drive. Great stuff.

The first regular season overtime game was a tie. The Broncos blocked a 25-yard field goal attempt by the Steelers’ Roy Gerela at the end of regulation; their own placekicker, Jim Turner, then missed a 41-yard attempt that would’ve given them the win in OT. It ended 35-all. “This game was destined to be a tie,” Broncos coach John Ralston said. The Jets were the first winners of an overtime game, beating the Giants 26-20 in November. (Thanks to what I can only imagine is an optical character recognition screwup, the current New York Times headline on the recap of that game is: “Jets Doon Giants On Ivan Namath’s Pass In Overtime, 26‐20.”) Joe, not Ivan, Namath hit Emerson Boozer (not a typo) for a 5-yard touchdown for the first overtime win in a regular season game.

Overtime rules have seen stayed pretty much the same ever since. Games rarely end in ties anymore, even with the NFL making some changes recently. In 2010 the NFL changed the rules just for the postseason—if the team that won the coin flip scored a field goal on their first possession, they would have to kick off afterwards. After that, the game became sudden death. A first-possession touchdown still won the game, as when Tim Tebow hit Demaryius Thomas to beat the Steelers in 2012 on the first play of OT. (Ref Ron Winters took forever to explain the new rules before overtime, which didn’t end up mattering anyway.) In 2012 the NFL expanded this rule to regular-season games as well. In 2017, supposedly for reasons of player safety, the NFL shortened regular-season OT to just 10 minutes; playoff OT stayed at 15.

When the NFL changed the rule in 2010, teams that had won the overtime coin toss were 7-7 in postseason games over the past 16 years. After the rule change, which was an attempt to give the team that loses the coin toss a better chance, teams that win the coin toss are 10-1 in playoff OT games. (The Saints, in the NFC title game in 2019, are the only coin-toss winners that went on to become losers.) Seven of those eventual winners scored a TD on the opening possession. Regular season, with its larger sample size, is much closer since the 2012 rule change: Teams that win the toss are 86-67-10. Still, it seems unfair.

Teams have attempted to introduce a variety of rule changes in the last decade-plus, to no success. In 2019 Kansas City tried to allow both teams to get the ball in OT; in 2020 Philadelphia wanted OT possession to favor the team that had scored more touchdowns in the game. A joint Eagles/Ravens proposal last year was called “spot and choose,” wherein the coin toss winner could elect to get the ball or where the ball would be spotted to start overtime. All of these proposals failed.

With overtime rules once again making national news after the Bills’ loss to the Chiefs on Sunday, more rule change proposals are sure to happen. One thing we can take from league history is the certainty that, no matter what’s decided, a lot of people are going to hate it.