A line about the experience of reading, possibly first spoken by the young actor Zoe Colletti in the 2019 film adaptation of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, is that you don’t read a book, the book reads you. Applied to something other than haunted books, which was Colletti’s usage, the statement suggests that because each reader brings their unique point of view to a work of art, our experience of that book reveals something not just about the work but about ourselves. We find our own preoccupations loose in the pages of works that couldn’t possibly have taken notice of them. This is what makes reading fun.

In this way, it is entirely reasonable that Hoopla, Harry Stein’s 1983 baseball novel about demagoguery framed around the Black Sox conspiracy to throw the 1919 World Series in service to gamblers, seems very much like a work about the present moment. It’s a book that says very little of importance about baseball, but which does a great job of explaining how a country might come to find itself spending the better part of a decade as (mostly) unwilling participants in the Donald Trump Extended Universe. Hoopla depicts an America in which news and entertainment have become so thoroughly muddled and cynical that stories derived from human pleasure and pain, fortune and misfortune, have value only insofar as they can be torqued so as to serve one agenda or another. Truth still exists in this world, but it doesn’t really matter.

In the years since writing Hoopla, Stein refashioned himself as a loudly lapsed liberal of the “I didn’t leave the Democratic party, the party left me” variety. As with many such transformations, some of his political devolution seems related to discomfort with what he perceived as the left’s effort to wean American culture away from persistent, casual racism. Stein built a second career as a sort of public intellectual who opposed things like stigmatizing ethnic or racial humor, and who stayed mad about the cancellation of the radio minstrel show Amos & Andy for decades after it went off the air; after dropping the N-word in public and absorbing some related public humiliation, Stein claimed to have made “more and better Black friends than ever before.” In 2005, the critic James Wolcott referred to Stein as “a skullful of mush.” This is relevant here as proof that even someone who wrote an extremely perceptive novel about the process was vulnerable to hoopla-induced brain rot. Anyway, the book is much more interesting than its author.

Hoopla sets up parallel narratives in which the rise of fictional journalist Luther Pond—something of a mashup of columnists Walter Winchell and Westbrook Pegler, both of whom pursued red-baiting for fun and profit—is juxtaposed with the fall of White Sox third baseman Buck Weaver. The 1944 death of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the hypocritical commissioner who banned the Black Sox for life, inspires Weaver to write his memoirs, in which he depicts himself as a disillusioned innocent who ends up banned from baseball despite not participating in the fix.

Pond is a knowing cynic who learns and cares nothing about the lives destroyed through the hoopla of the title—extravagant promotion or publicity, per the dictionary headline—and more specifically the chase for sensationalistic hype and headlines where the Black Sox were concerned. Heroes and villains change places mostly through manipulation by the media. Hoopla’s parallel tales mostly keep to themselves: One is a bildungsroman of a hack’s progress, the other a lament for what happens to people once hacks get hold of your story and use it for their own purposes.

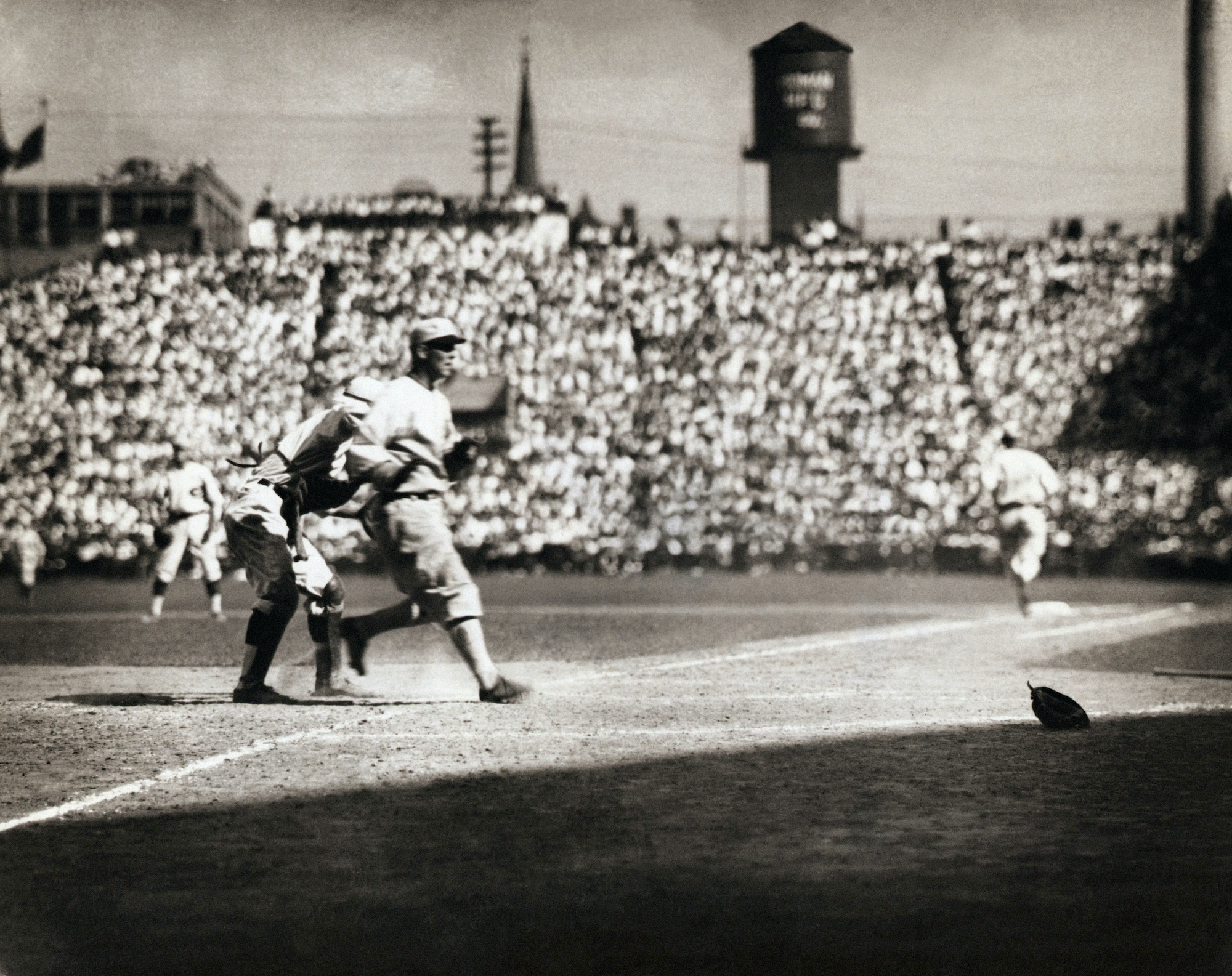

Weaver is the party on the wrong end of that business. A shortstop and third baseman for the White Sox from 1912 through his suspension at the end of the 1920 season, Weaver has long been an irresistible lure to sentimental storytellers. This has proven true whether the teller of the Black Sox tale is Stein, Eliot Asinof, or John Sayles, all of whom portrayed Weaver as a man who played to win and nonetheless found himself banned for life. Stein’s politics, we’ve been over; Asinof (who wrote the book Eight Men Out) and Sayles (who directed its movie adaptation and co-wrote the screenplay with Asinof) represent something like his polar opposite. But any sort of writer telling this story will need a Weaver figure. Without this distortion, the Black Sox narrative lacks a satisfying center. No figure in that universal greedfest rose to the level of Shakespearian tragedy; even Shoeless Joe Jackson, the best player involved in the scandal by far, just drifted along, taking the gamblers’ money (after it was literally thrown at him) without opting in or opting out. We will never know if the players first approached the gamblers or if both sides hit upon the scheme independently. This hinders the search for sympathetic characters. There’s no one to root for when everyone sucks.

Weaver doesn’t solve that problem, so Stein plays pretend. Weaver really did hit .324 in the eight-game World Series, and this normally very butterfingered infielder didn’t make a single error. That he was nonetheless banned made Weaver a martyr, especially to himself, and it allows a book like Hoopla to present some powerful if sometimes dishonest juxtapositions. Stein compares the conspiracy to fix the World Series with the brokered Republican National Convention of 1920, quoting Warren Harding’s eventual attorney general, the spectacularly corrupt Harry M. Daugherty, as saying the nominee was picked “in seclusion around a big table, by fifteen men, perspiring profusely and bleary-eyed with loss of sleep. Just a nice bunch of fellows cutting a deal.”

This is a red herring. Whether Weaver played to win or not, he was not a martyr; he had guilty knowledge of the fix and chose to keep it to himself. This made him an accessory to a conspiracy, whereas a brokered convention isn’t a conspiracy against the public trust, no matter how poor the results—it was the recognized selection process at the time, for one, and at no time was the public forced to vote for the selected candidate, whereas the outcome of the 1919 World Series really was both brokered and ordained. (It is a fortunate thing that Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the 2024 presidential race and Kamala Harris’s concomitant elevation to the top of the ticket occurred over 40 years after this book was written; the comparison would have been inevitable, especially for Stein, but similarly inapt.)

Similarly, Hoopla concludes by contrasting Weaver’s fate with the resolution of the 1926 Ty Cobb-Tris Speaker affair. When an old game-fixing arrangement surfaced, the two greats were convincingly implicated, Cobb more so than Speaker. Both were ultimately exonerated by Landis. Cobb, in Stein’s telling, was the beneficiary of superior “hoopla” to Weaver, but for all the confluence of money and power and fame and hype carried him just as guilty of fixing a game—and maybe more so, given that Weaver played to win. Landis’s decision, as well as his role as the judge who squelched the Federal League challenge to the American and National League cartel prior to becoming the commissioner, can certainly be questioned. Yet the commissioner’s very real hypocrisy does nothing to vindicate Weaver’s decision to show greater loyalty to fixers like Chick Gandil and Swede Risberg than to the integrity of the game and his own honor.

Stein is on firmer ground when he has Weaver relate the story of Francesco Stephano Pezzolo, known to baseball history as Ping Bodie, the only player ever to indirectly murder an ostrich via eating contest. Bodie, who was with the White Sox from 1911 to 1914, was an accomplished hitter, but failed to stick in the majors. According to Hoopla’s Weaver, that wasn’t Bodie’s fault, but that of the sportswriters who focused on Bodie’s eccentricities over his talents:

“Bodie was indeed a character and a half… and he ran as slow as a seven-year itch. One time when he tried to swipe a base, some scribe wrote down that ‘his head was full of larceny but his feet were honest,’ which is about how it was. And that is the sort of thing they were always putting down about Ping, that and what a bragger he was, which I must admit was also true… Only, the thing was, there was another part to Ping… and it never got in the papers at all. See, he was not only a daffydil, but also a player with amazing skills. When he landed with the lumber, the horsehide took a regular expedition with Byrd. He could lace the ball as long as any ballplayer I have ever seen, even including the Babe, but he never got any kind of real chance to show off his stuff, on account of everyone taking him for such a bean skull… And so old Ping was sent back to San Fran. He never did forget what [White Sox owner Charles] Comiskey had done to him, nor the scribes neither, for he would tell anybody that asked him the same thing. ‘Those fellows just do not have no sense of responsibility.’”

Conversely, here is a vision of responsibility from Stein’s 2012 book No Matter What… They’ll Call This Book Racist: “Far too many black people, as well as legions of white liberals, have opted for… a definition of racism so expansive that almost anything—from the failure of too few blacks to pass an exam for promotion to a perceived slight at a social function—can be made to fit the bill.”

The Stein who wrote those words about Bodie would have recognized the place of entitlement and cruel complacency from which those later sentences were written. The hallmark of the “Why can’t you just take a joke?” lobby is the insistence that those who haven’t suffered a given form of insult or discrimination have a right to tell those who have when they’re being too sensitive—and that those Polish jokes, or the career-wrecking caricature of an outfielder just trying to make a living, are just too much fun to give up. Stein’s later embrace of overdog resentment is anticipated in Hoopla through the grandiose Pond’s opening narrative:

Never before in my long experience has this nation been in such sorry condition as it is today. Never before have the values upon which I was nurtured been in such desperate need of affirmation… I stand as eager as I was 50 years ago to take on the world’s self-righteous, those infuriating souls who believe they’ve got a corner on conscience and integrity and every other quality that might conceivably get a man into heaven.

No one had even called him “deplorable.”

Nothing in Hoopla vindicates values; the book is an exploration of their absence. “Conscience and integrity,” what one might otherwise call an awareness of inclusivity’s possibilities and some sensitivity to its role in the civic function of an increasingly diverse nation, is actually pretty easy. Or it could be, provided a person isn’t so narcissistic as to feel oppressed simply because they don’t feel sufficiently free to oppress someone else. If someone’s dignity is wounded by the story one tells, or the way one has told it, basic empathy requires a person to ask if the yuks were worth their pain. That answer is often going to be no. At least that’s what Ping Bodie, victim of hoopla that he was, would have told you.

This is not a complicated concept. It is the stuff every successful relationship is made of. The problem is not that anyone aside from true narcissists struggle to grasp this, but that, to borrow from Upton Sinclair, it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary—or his social or political standing—depends upon his not understanding it. This is the business of hoopla: It is valorization or demonization for profit, elevated over any attempt at empathetic understanding, and always, always juxtaposes “we” and “us” against “they,” “them,” and “those people.”

In putting the journalistic reveal of the Black Sox conspiracy in the hands of his Winchell stand-in Pond rather than the man who actually uncovered it, the dogged journalist Hugh Fullerton, Stein illustrates the contingent way in which winners and losers get picked, then and now. Back in 1919, Fullerton was “utterly disgusted with the [corruption in baseball] thing,” and wanted the truth to come out so that the game could be cleansed; in Hoopla, Pond pursues the story because his livelihood depends upon delivering a steady supply of nastiness and innuendo. The former is public-interest reporting, the latter more equivalent to the horse-race political coverage that has long distorted American presidential elections.

This is not the only way the national relationship with both sport and the concept of integrity have been degraded. Every baseball book concerning the first half of the 20th century takes the centrality of baseball to American culture as a given; it feels as unlikely and antique as tulipmania. Consider this introductory passage from Lore and Legends of Baseball by Mac Davis (1953):

For Americans, there is no other game in the world like baseball. The national pastime is rooted deep in their hearts. It has become a way of life and something of a religion, generating the pure essence of joy. Baseball has become part of our national character, part of our culture, and part of our faith.

It is also democracy at work, for the game reduces people from all walks of life to a common denominator. Once a baseball game is on, everybody wants to get into the act.

The famous F. Scott Fitzgerald line about the World Series fix from The Great Gatsby, said of his stand-in for the fix’s financier Arnold Rothstein, springs from this same sense of the game’s importance to American identity. “It never occurred to me,” Fitzgerald writes, “that one man could start to play with the faith of fifty million people—with the single-mindedness of a burglar blowing a safe.”

This now seems ridiculous. Maybe it was inevitable that baseball would not have the same importance to a country of 333 million that it had to one so much smaller, and yet even in 1925, Fitzgerald should have known better. The nation had already gotten over the shame of the Black Sox by then, seduced by Babe Ruth’s home runs and the headlong hedonism of that decade. In our own time we’ve experienced the cancellation of a World Series, PEDs, and Astros trashcan-banging among other things, and nothing happened. We just accept that baseball is as cynical and dishonest as our politics, or any of the other little shadow plays unfolding in the twilight of the empire. There is nothing to believe in but the ubiquity of hoopla, which means that reality is functionally extinct. If everything that happens—a mass shooting, a pandemic, wildfires or, least significantly, a World Series—scans more like just another story to project some politicized opinion upon to millions of people, then our hoopla providers have been so successful in their efforts. In place of any kind of common experience is a field of noise.

The difference between Buck Weaver’s day and ours was that the “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend” ethos mainly affected him and his prospects. Our hoopla—create your own facts, drill them relentlessly—is a call to mass action or inaction, approbation or condemnation. Nelson Algren began his prose poem about the Black Sox, “Ballet For Opening Day” with the subtitle “The Swede Was a Hard Guy.” This was Joe Jackson’s explanation for why he didn’t inform on the fix—the shortstop Risberg had threatened to hurt him. It is a reactionary truism at this moment—in many moments before, too—that the nation is all out of hard guys. The idea is that the nation lacks appropriate moral outrage, that it meekly goes along and takes what it’s given; this is true enough, if not in the way the reactionaries mean. Americans absolutely do accept the relentless and multi-front degradation of our civic life, if only for lack of recourse, but that’s not what the practitioners of hoopla are mad about.

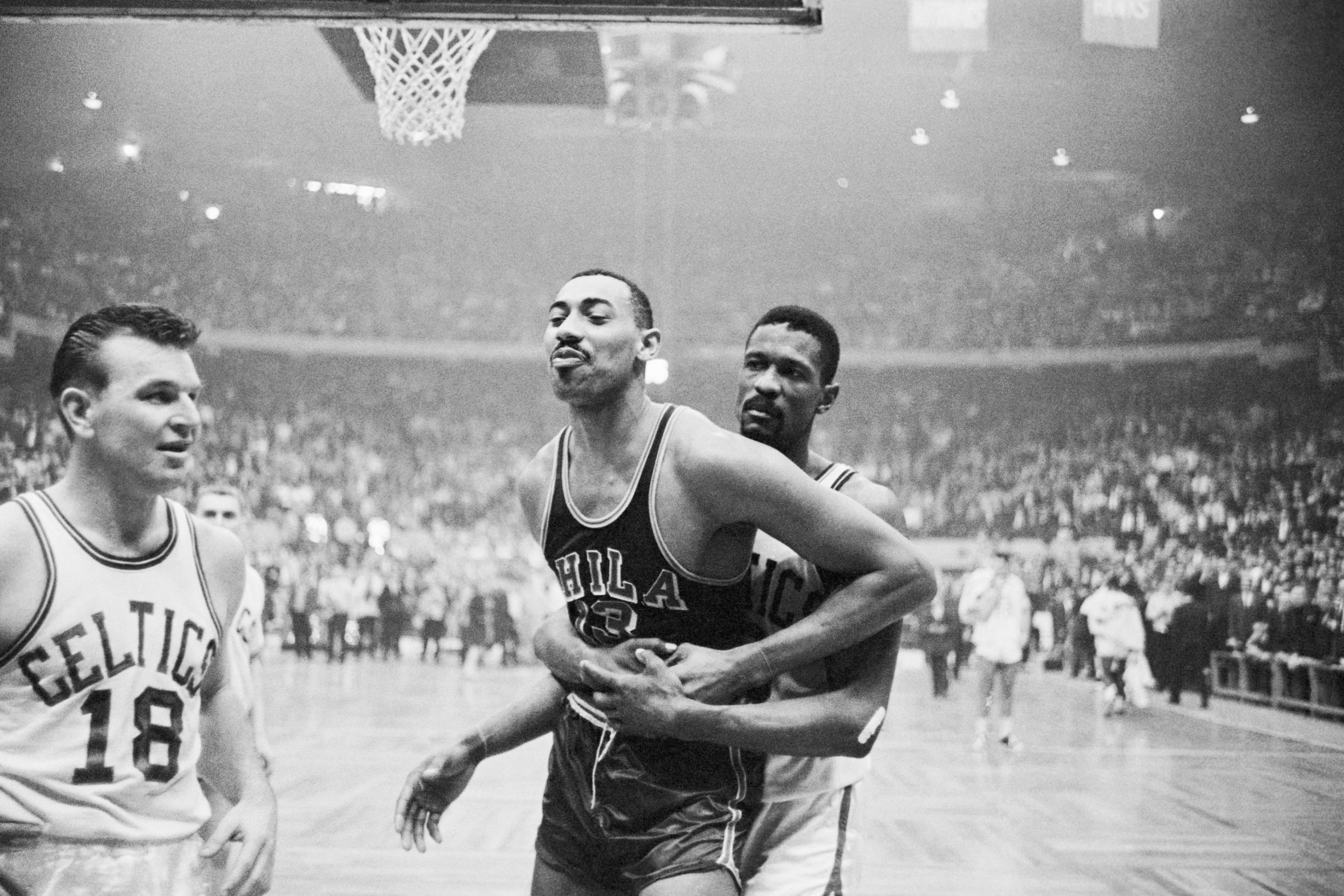

Hoopla is incisive, and stands out in the surprisingly large field of Black Sox-inspired literature because it isn’t just tragedy porn. But it’s also a disheartening book to read in this moment. There is the sense that 105 years later, the culture hasn’t learned a damned thing. (Perhaps coincidentally, this is also the theme of Bernard Malamud’s The Natural: “I never did learn anything out of my past life,” Roy Hobbs concludes, “now I have to suffer again.”) One of the formative incidents of Pond’s career is the 1910 Jack Johnson-James Jeffries heavyweight boxing match, billed as a nigh-Darwinian battle for supremacy between the Black Johnson and Jeffries, named “the great white hope” by Jack London. This case of murderous crowd-hyping—when Johnson beat Jeffries, more than two score people were killed in race riots—wasn’t the birth of modern hoopla. The “you furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war" newspaper frenzy in the run-up to the Spanish-American War a dozen years earlier seems a better candidate.

But the manipulation of the public’s baser instincts surrounding that fight, when considered next to the last presidential campaign’s overtly bigoted incitements about “importing the third world” and the attendant threat to America’s pets, suggests a country that has refused to learn anything more or less on principle. There is still good business to be done in willing problems into existence, and in keeping them alive for as long as they can keep the masses hooked on both a pathetic credulity and the masochistic dopamine hit that comes from the conviction that someone, somewhere is lying to you.

Buck Weaver’s life ended in January 1956, on Chicago’s 71st Street. He was on his way to see his accountant when he had a fatal heart attack. Nothing is certain but death and taxes, Benjamin Franklin said; Weaver was claimed by both at once. The 20th century expanded that maxim, and the 21st has piled it on. Nothing, now, is certain except death, taxes, and hoopla. Guilty or not, Algren’s description of Buck Weaver fits cleanly over the broader moment:

A joyous boy, all heart and hard-trying

A territorial animal

Who guarded the spiked sand around third like his life.

And wound up coaching a girls softball team

With no heart left in him at all.