Steven Soderbergh made The Limey for $10 million in 1998, and by his own account had an absolutely miserable time doing it. Or, more specifically, he made it briskly and seemingly happily, then reconfigured it, even more hastily and much less happily, into a film that would go on to make less than a third of that budget back at the box office and, sometime after that, be recognized as one of the most distinctive and stylish thrillers of its era. The film that ultimately attracted that cult is a lean, nasty, intermittently dreamlike 90-minute revenge story that follows a grieving, absent father on a quest for revenge; the film that Soderbergh screened months earlier was a much more straightforward effort, and also straightforwardly a disaster.

"It felt like there was nothing to salvage," Soderbergh remembered during an interview with Deadline in 2019. "In the immediate aftermath of that first screening, it felt like nothing worked. That’s how scared we were at that moment." Over the course of several months, Soderbergh and editor Sara Flack effectively remade the film, first through some reshoots and then by reimagining it in the editing room. "It wasn’t written or shot to be put together the way it ended up being put together," Soderbergh said. The director mentioned in that interview that, until he revisited it for the film's 20th anniversary remastering, he hadn't watched The Limey at all since finishing that edit. For context, this is a man who watched William Friedkin's Sorcerer three times in 2022 and famously never misses an episode of Bravo's Below Deck franchise. Given that Soderbergh uses the phrase "vortex of terror" to describe the film's post-production elsewhere in that interview, we can probably give him a pass.

But I, as someone who loves The Limey and is much less busy than Soderbergh, also hadn't seen it in 20 years before I returned to it last week. The occasion was the recent death of Terence Stamp, the film's lead actor and central presence; the film's on-screen title reads "Terence Stamp In The Limey," which does not remotely overstate how important he is to making the broader enterprise work. You do not need to know about Stamp's long and eventful life—that he was extremely famous and something like the Consensus Hottest Living Dude On Earth in the 1960s, that he bailed on acting and lived on an ashram for much of the 1970s, that he returned as the villain in Richard Donner's Superman and worked steadily as a character star more or less until the end of his life—to appreciate the work that he does in The Limey. But some knowledge of Stamp's actual life in and out of pictures, and of the strikingly large number of other '60s counterculture eminences in the cast, adds a strange and mournful depth to the film.

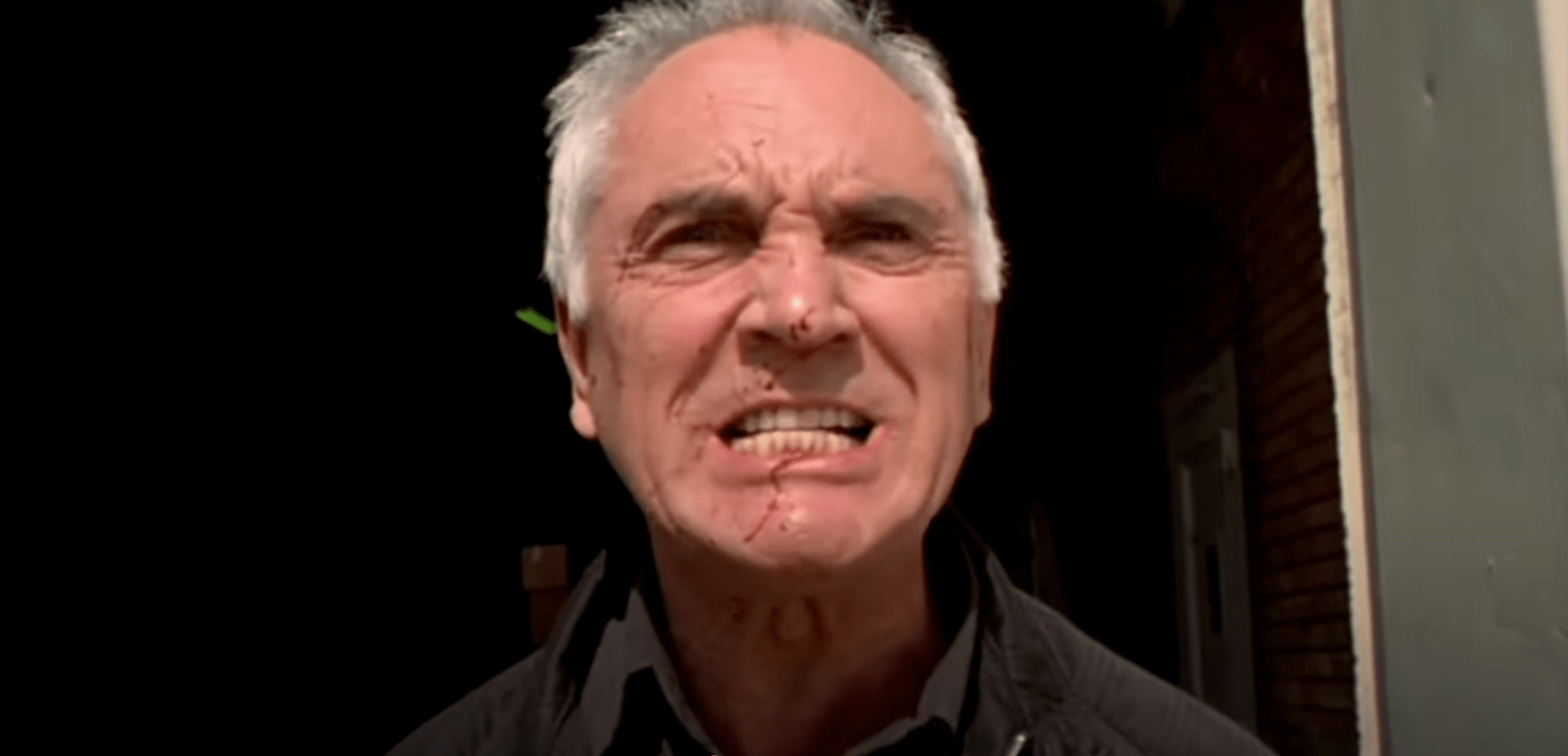

Stamp is astonishingly good in The Limey; his single-minded Wilson, a career criminal dead set on committing some more crimes against whoever was behind the death of his estranged daughter, is an unsettling and reptilian presence throughout, and the moments when he erupts in rage or violence are all the more jarring for how even and placid his eyes remain while he does or just dreams of all the trouble he has in mind. There is no release in any of it, and ultimately no meaningful vengeance, either—what is gone cannot be brought back, and the time that Wilson lost in prison and the distance that absence created in his relationship with his daughter cannot be made up in the present. Stamp's stare, which is utterly emptied out, suggests that there's not much chance any of that will be made up in the future, either.

The most obvious film comparison, which Soderbergh and screenwriter Lem Dobbs have both made, is to John Boorman's ultra-dark 1967 revenge thriller Point Blank, in which a crook who had been left for dead by his partner chases the people that wronged him and the money that he believes is rightly his, and comes up bloodily, brutally empty. But every revenge movie that's remotely honest with the audience is at least a little bit like this; none of this vengeance solves anything, and nothing really even resolves. The dreamlike ambiguity that Soderbergh and Flack introduced into the film in that frantic post-production reimagining—audio and image slip in and out of sync at strange times; the perspective and even the narrative skips and scans around; the film turns and returns to Wilson seething and silent in an airplane, either remembering or fantasizing it all—plays like memory. That is, it moves around in strange ways, but is finally pacing around within a space that is inherently and narrowly proscribed. Stamp's performance, and Soderbergh's visuals, suggest that whether Wilson is literally incarcerated or not is beside the point. He's all the way inside, and not getting out.

There is another, sadder ghost haunting The Limey, and that is the bygone era in which Stamp and so much of the cast were young and beautiful and primed to take over the world. Peter Fonda plays the object of Stamp's vengeance, a music promoter who got rich selling the '60s and now drifts, bored and vain and much more desperate than he seems, through the luxurious life that transaction got him; there is still some of Fonda's Easy Rider rakishness in the character of Terry Valentine, but whatever all that once might have been about, it is plainly now about business, and survival. His glowering chief of security is played by Barry Newman, who was young and handsome in the existential cult movie Vanishing Point in 1972, and looks kind of like Sydney Pollack's sadistic nephew in 1999. One of the thugs in Newman's employ, who is mostly a hulking and silent counterpoint to the late Nicky Katt's motormouthed sociopath Stacey, is played by Joe Dallesandro, who was one of Andy Warhol's beefcake Factory muses in the 1960s and whose crotch Warhol photographed and put front and center on the cover of the Rolling Stones' 1971 album Sticky Fingers. The main actors in the film are all older; Lesley Anne Warren and Luis Guzmán play friends to Wilson's daughter, but they are both denizens of a very different working-class Hollywood—Guzmán mentions that he met Wilson's daughter in acting class—than Valentine. The younger people in the film are either the victims of those '60s survivors, like Wilson's daughter, or their cosseted prisoners, like Valentine's new girlfriend, or their unhappy charges, like the wildly bilious and bitter Stacey. The damaged and secretly desperate people that squandered their optimistic youth, or betrayed it, or just sold it, are still in control.

One of the hazards of watching too many movies is that connections like these tend to come maybe more readily than they should; Bill Duke, who appears in a critical unbilled role, was almost certainly not cast in The Limey because Soderbergh expects viewers to remember him from American Gigolo, and was most likely just cast because Soderbergh, wisely, enjoys casting Bill Duke in his productions. (He's done it twice since.) But for all the things that haunt The Limey—the relationship Wilson had and lost with his daughter, the dream of transcendence that Valentine turned into money and stuff, the hungry ghost of Wilson himself—none of them hangs around quite like regret, and the sense that things might have been otherwise if some decisions made in the distant and irretrievable past had been made differently. Soderbergh literalizes this where Wilson is concerned by cutting in black-and-white footage of Stamp from Ken Loach's 1967 film Poor Cow. Wandering through the film's prison yard of memory, that other vision of Stamp—young, beautiful, happily wrestling with his girlfriend or picking out a song on a guitar—seems like another character entirely, maybe somebody that you used to know or maybe not.

Stamp was by all accounts a gracious and good-humored guy, someone who took his work seriously and understood what it was in a straightforward way. "I’ve done crap, because sometimes I didn’t have the rent," he told The Guardian in 2015. "But when I’ve got the rent, I want to do the best I can." He was a working-class kid who became a working actor, a sort-of-star who could do a very specific thing better than most anyone else and made a life doing it. But the person Stamp was in the 1960s, when he was one of the most famous and in-demand people in the popular culture, didn't survive that decade. "When the 1960s ended, I just ended with it," he said in that Guardian interview. "I remember my agent telling me: ‘They are all looking for a young Terence Stamp.’ And I thought: ‘I am young.’ I was 31, 32. I couldn’t believe it." When he received a telegram on that ashram alerting him to the fact that he'd been cast in Superman, in 1976, it was addressed to "Clarence Stamp."

Both that sudden disappearance and the strange experience of surviving it are there in Stamp's performance in The Limey, and in the film itself. The past haunts the present, and everyone in it. In the story of The Limey, this is extremely literal; that is what the character of Wilson is. But in the dreamy fragments that Soderbergh and Flack used to rebuild The Limey as a film, the past is something stranger and sadder—not an external force seeking vengeance in or against the present, or not just that, but something more like that moment's ghostly twin. It's a presence in every beautiful and anxious space, asking and asking and asking over again how things might have been different.