For health and safety reasons, I have been trying to ease myself away from White Sox baseball, and have chosen the Seattle Mariners as a tentative American League replacement. This will surely not harm me. We're already seeing excellent results, in fact. Just yesterday, Cal Raleigh proved my point by smashing an absolute meatball for a walk-off grand slam against the White Sox, in a game that the White Sox were originally winning 4-0.

Ah, that feels both good and terrible at the same time. But this is not about Raleigh's heroics, or even Logan Gilbert. This post is about one of my current favorite pitchers in the Mariners rotation, which is filled with fun and interesting pitchers. That pitcher is Bryan Woo, and I'll admit here that some of my fascination with Woo comes from a sense of kinship in that we both bear the less-popular, y-enhanced spellings of our given names. But he's also very cool, and because he will be facing the White Sox tonight, he can be expected to look that way for at least one more start. Update (6:55 p.m. ET): Woo has been scratched from tonight's start, and the team is waiting for MRI results on his right arm.

Woo missed the start of the season due to right elbow inflammation, and the team has eased him back into the mix. He's only made six starts, all on relatively limited pitch counts, and so is not yet a qualified pitcher for most leaderboards. But in those six starts, which span 33.2 innings, Woo has a 1.07 ERA, 24 strikeouts, and only two walks; these are the best six starts to open a Mariners pitching season ever, topping Randy Johnson. Two walks against 24 strikeouts is a K/BB ratio of 12, which is higher than any qualified pitcher so far this year, but not by as much as you'd think. Woo's strike-happy teammate George Kirby is currently rocking a 11.14 K/BB ratio over 14 starts. Lots of fun and interesting pitchers in this rotation!

This may or may not be sustainable, but any pitcher who's able to put up those sorts of numbers over six consecutive starts deserves a closer look. Woo especially deserves a look, because he is baffling. Look at Paul Skenes, and it's clear exactly how he does what he does. Or, at the opposite end, you can look at Shota Imanaga, and it's clear how he does what he does, too. But Woo isn't really like either. Unlike Skenes, he is not a power pitcher with overwhelmingly nasty stuff—at a glance, his four-seamer hits a more or less average 95 mph with respectable-but-average movement; his second-most frequently used pitch, a sinker, sits at around 94 mph with average vertical break and slightly above average horizontal break. As long as Woo's heat maps look like this—here are Imanaga's four-seamer and splitter, for comparison—and he uses his fastballs a combined 78 percent of the time, he can't really be described as a soft(er)-throwing control pitcher.

And yet: Woo has generated 11 runs worth of value on his fastballs alone, which is 98th-percentile in MLB despite run value being a cumulative statistic. Nationals sicko Chris Thompson informed me that when Woo pitched in Washington, a Nats announcer was "raving about his fastball shape," whatever that means. Often, when a guy goes on my guy list, it's not just because of what they've done but because they've done it in such a way that it's amusingly devastating to my brain chemistry. My favorite players are ones that have baffled or awed me in some way, in some lasting capacity; the best comparison I can make, here, is to this Korean dog Instagram. I can't really describe what happened to me after Woo's last start against the Oakland A's except that, after dinner, I entered a sort of fugue state and that when I awoke from it just short of midnight it was with about 30 tabs open and a 1,000-word outline for a post about a pitcher I'd watched a handful of times. Welcome to the Bryan Woo rabbit hole—we're very happy to have you here.

In baseball, you're rarely the only person asking a particular question; a pitcher who is good enough, in a weird enough way, will invariably have a lot of people looking into how and why. Foolish Baseball did a video that basically started from the same point as my fascination with Bryan Woo, except through the lens of Reds closer Alexis Díaz. I highly recommend watching it, but the latter half of the video focuses on Vertical Approach Angle, a stat popularized by FanGraphs writer Alex Chamberlain that looks jargon-y but is ultimately pretty simple. VAA is the angle at which a ball approaches home plate, assuming the zero degree mark runs parallel to the ground, set at the pitcher's release point. Because pitchers are often tall, lanky, and elevated on the mound, your VAA will basically always be negative. Extreme VAAs test the awkward extrema of a batter's swing up and low in the zone, which makes it especially important for pitches like high four-seamers and low sinkers. For four-seamers, you want to get your VAA as high, or as close to zero, as possible; for sinkers, you want to get your VAA as low, or as steep, as you can.

In Foolish Baseball's video, you'll note that Woo crops up on Chamberlain's leaderboard. In 2024, Woo's four-seamer still ranks highly, with a -3.8 degree VAA in comparison to a -4.7 degree league average; restrict that to starting pitchers, and his four-seamer jumps up to third. VAA is unsurprisingly heavily correlated with pitch height and pitcher release point, and Woo's release point, which sits at just under five feet, is one of the lowest in the league—restrict that again to starting pitchers, which filters out weird-throwing reliever freaks (affectionate) like Tyler Rogers, and Woo has the fifth-lowest release point in MLB. Mechanically speaking, the reason why pitchers often have high release points is that it's easier to generate the spin that goes into making a rising fastball rise. When a pitcher throws sidearm four-seamers like Woo, you would normally expect less velocity and vertical movement and way more horizontal movement. And that's what you'll get from most of Woo's peers in the sub-five foot release point gang: JP Sears, Kyle Harrison, and Trevor Williams.

But Woo has been a lot better than those pitchers in large part because he is able to get league average velocity, spin, and movement from a very much non-league-average release point; suddenly, that average-looking rising fastball isn't very average at all. The pitch has the weird delivery aspects that make pitchers hard to face, and does things that pitches thrown from that weird delivery generally don't. Another player along Woo's mold is Joe Ryan, for the Twins. There aren't many others.

That helps explain what makes Woo's four-seamer pop, but not so much the sinker. A sinker, conversely, wants a steeper VAA; because VAA is heavily correlated with release point, Woo also has a relatively flat VAA for his sinkers, too. But the sinker has been Woo's both second-most thrown and second-most effective pitch after the four-seamer. So what's up with that one? The easiest explanation for this probably comes down to the pitching buzzphrase of seam-shifted wake, which got a quick rundown from Tom Tango back in 2021. Tango used Max Fried as an example, but Woo has a similar profile with his fastballs:

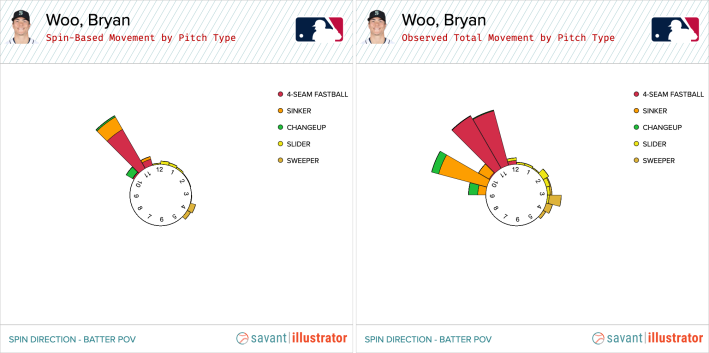

When looking at the spin of his fastballs at release (visualized in the spin-based movement chart on the left), his four-seamer and sinker are rotating along the same axis. Per traditional, right-hand rule based spin movement, you would expect these pitches to move the same way. Woo's don't, and it's because of how he uses the seams of a baseball to generate movement beyond spin. The movement of Woo's sinker, visualized in the observed total movement radial chart on the right, diverges significantly from the movement of his fastball, despite appearing the same out of his hand.

In his prospect overview of Woo last year, Eric Longenhagen noted that Woo's fastball usage between his four-seamer and sinker—then also clocking in at roughly three-quarters of the time—would be unprecedented among any starter in MLB; he wrote, quite sensibly, that the lack of development in secondary pitches might hold him back. This seems a fair consideration, especially considering how much an improved change-up could help aid in Woo's unhappy splits against left-handed hitters. But I think it's also worth consideration that, because Woo doesn't also have Max Fried's curveball, he uses his sinker the same way that most pitchers might use a slider or a change-up. That is, he uses it to play off of those four-seamers—batters read the ball one way out of his hand, and it winds up doing something entirely different on its way to the plate. This seems strange, using one fastball to set up and play off another. But it sure passes the eye test.

Bryan Woo, Wicked 95mph Front Door Two Seamer. 🤢 pic.twitter.com/zpC773ilOi

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) June 6, 2024

It's fun to try and figure things out, but what really gives Woo elevated guy status in my mind is how he approaches the zone. He does this with all the methodical patience of a bull noticing a red flag—Woo charges right at the zone, over and over. If Woo's teammate Kirby hadn't let off the gas a bit this year, we'd probably still call it the George Kirby school of pitching, but right now we can call it the Cole Irvin–Zach Eflin–Tarik Skubal school of pitching. Either way, Woo's attendance in class has been excellent; he has thrown 62 percent of his pitches in the zone. League average sits at around 50 percent—the current qualified MLB leader, the aforementioned Cole Irvin, is sitting at a mere 57 percent.

Here is the breakdown of Woo's in-zone percentage based on if he's behind, even, or ahead in the count:

- Behind in the count: 75.3%, 2nd in MLB (min. 50 pitches)

- Even in the count: 62.2%, 9th in MLB (min. 100 pitches)

- Ahead in the count: 54.1%, 6th in MLB (min. 100 pitches)

That is to say, even when Woo is ahead in the count and has some pitches to burn, he still throws pitches in the zone at a rate above league average. As you might anticipate from the minimum pitch drop for behind-the-count pitches in the above breakdown, this kind of approach means that Woo just doesn't fall behind very much. Here is the breakdown by count, along with the number of total pitches he's thrown in each count (counts where he's behind are italicized):

- 0-0: 70.3%, 118 total pitches

- 0-1: 55.7%, 70 total pitches

- 0-2: 42.9%, 42 total pitches

- 1-0: 68.8%, 32 total pitches

- 1-1: 50.0%, 42 total pitches

- 1-2: 62.2%, 45 total pitches

- 2-0: 100.0%, 7 total pitches

- 2-1: 72.2%, 18 total pitches

- 2-2: 48.5%, 33 total pitches

- 3-1: 50.0%, 2 total pitches

- 3-2: 80.0%, 30 total pitches

This means that out of the 439 total pitches Woo has thrown this year, only 89, or about a fifth of them, have come while he's behind in the count. But I know what you're really thinking, looking at the above breakdown: Where are my 3-0 counts? Sir, sir, you've left off the 3-0 counts! Respectfully, asking this makes you sound very foolish. You think Bryan Woo allows 3-0 counts? The man throws the ball in the zone 70 percent of the time to open an at bat, and you think he's seen a 3-0 count this year? He's only seen a 3-1 count twice! Bryan Woo is an honorable pitcher—he doesn't nibble around the strike zone. The only time he's more likely to throw outside of the strike zone than in it are on 0-2 and 2-2 counts. He'd rather give up a hit rather than a walk, and I know that's right.

I also understand that Woo gave up three runs against the Nationals in his worst start so far, blah blah blah, but here are my Bryan Woo lowlights:

It's a short reel. Since allowing a walk to Kyle Isbel in his second start back from injury, Woo has yet to allow another. In that same span of time, he's pitched 24 more innings and racked up 16 strikeouts. It's way, way too early to start looking at the leaderboards, but it's impressive nonetheless. The man simply does not walk batters, because walks are for infants in prams and cute Instagram dogs frolicking in the grass on Jeju Island. Bryan Woo does not have time for this sort of thing. There are strikes to throw.

But this is over six starts, and while it is working very well, it is tough to escape the sense that there's simply no way an approach like this is sustainable. The reason why pitchers don't throw the ball in the zone that often is because it doesn't usually help. Woo is getting really bad contact on his pitches so far, but his low whiff rate, considering both how much he throws the ball in the zone and how often batters swing at those pitches, is concerning. He's also currently rocking a 2.4 percent home run to fly ball ratio; league average hovers closer to 16 percent, and that suggests a correction is in the offing, too. So far, he's faced the A's twice and the Yankees, Nationals, Royals, and Angels once—out of those five teams, the Yankees are arguably the only one that presents a significant challenge. And even with the new focus on his change-up, Woo is still not great against lefties. Thanks to pitch limits due to his return from injury, he also hasn't had to see most batters more than twice, which is a very good thing for his 78 percent fastball rate—he doesn't fare particularly well the third time through the order.

The flipside of all this is ... well, everything you've already read. It's working; Woo has gone six innings in each of his last four starts and only once had to break 80 pitches to do so. Perhaps "throw it in the zone" has been a directive from the Mariners pitching staff to help get him right as he recovers from his injury; it's very hard to imagine Woo or anyone else maintaining that through the remainder of the season, even though I would selfishly like to see it. Some of this is hard to imagine because no one has really done it before, but there's something to that.

Woo is only in his second year, and so very much still in the part of his career in which he is actively figuring things out. He has already dramatically changed his approach with his secondary pitches—fewer sliders and sinkers, more change-ups to left-handed hitters. Perhaps the most surprising outcome of all would be if Woo looks exactly as he does now just a few months from now, much less a season later. But until then: Hell yeah, brother, throw it in the zone.