Aryna Sabalenka did something unusual in her Miami Open semifinal with Jasmine Paolini: She visibly acknowledged an error while a point was still live. Between points, anything goes in tennis. Players eviscerate their rackets, scream at umpires, spew abuse at their support team, or send tennis balls caroming around stadiums. But live rallies themselves are treated like a sacred space, free of even an eye-roll as long as a chance to win the point remains.

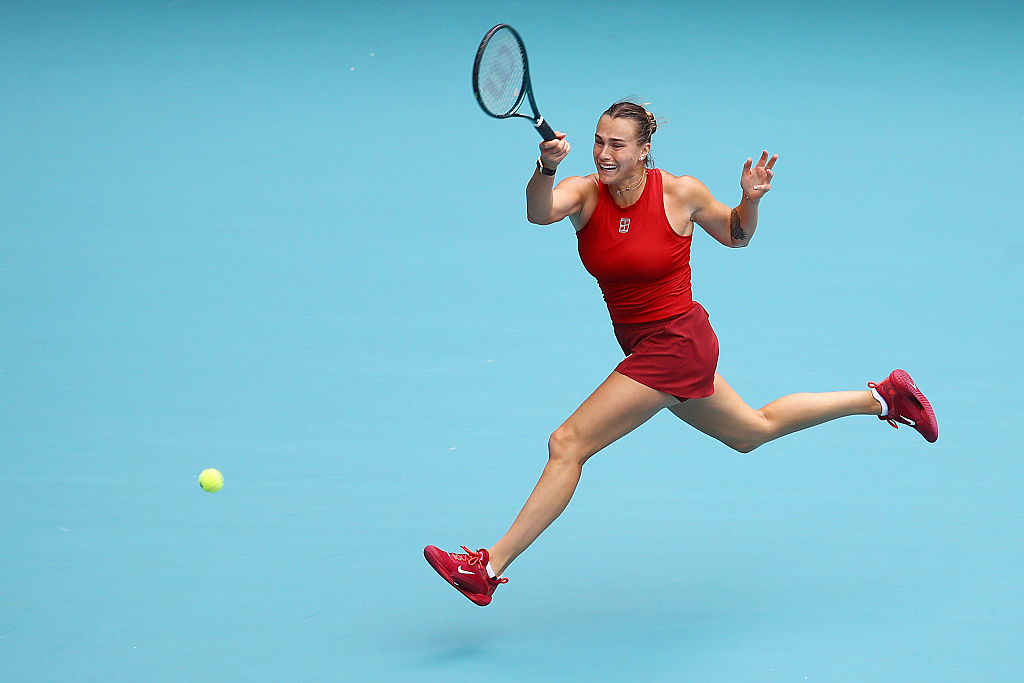

It happened when Sabalenka, the best player in the world, was leading the first set 4-1 and nearing another break point. She had Paolini scampering with a forehand missile but put a little too much air under a drop shot, which Paolini spun into a lob over Sabalenka’s head. On replay, as Sabalenka sprinted to retrieve it and saw the ball land in, she was already grimacing at surrendering control of the point.

After Paolini put away Sabalenka’s desperation tweener with an easy volley, Sabalenka put her face in her hands and swiped the air with her racket, dropping it to the ground. She had a smile on her face but was clearly ruing the drop shot’s excessive depth, or her decision to hit a drop shot at all in place of another forehand haymaker, or both. After all that, she applauded Paolini’s effort, tapping her racket strings with her palm. Theoretically, the point meant little to Sabalenka, who was well in control of the set anyway. But it seemed to drive her through the entire spectrum of emotions.

Paolini, ranked No. 7 on the WTA Tour, hit 19 winners and nine unforced errors in the match. This is an unusually positive ratio that tends to lend itself to dominant wins. Sabalenka won the match 6-2, 6-2.

Sabalenka holds herself to freakishly ambitious expectations because she can meet them. She won the Miami Open without losing a set, breaking her opponents’ serve more times than they could hold. She is 3,000 points clear of her closest chaser in the WTA rankings—roughly as many points as the No. 12, Daria Kasatkina, has in total. Sabalenka has made the quarterfinals or better at the last nine majors she has played, the longest ongoing streak on the WTA or ATP. During that run, she won three of them and lost in a semifinal or final five times. At one point in every single one of the losses, she had a lead and looked the likely winner.

Along with her TikToks and her piercing grunt, Sabalenka’s calling card is the raw pace on her shots. When tournaments compile leaderboards of participants’ average forehand speeds, Sabalenka often exceeds not just all her WTA peers but the male players, too. But devastating groundstrokes are only her foundation. In recent years, Sabalenka has folded touch shots into her game, producing the odd net rush or drop shot to complicate her style’s pounding rhythm. She does not defend like Coco Gauff or Iga Swiatek, but a player so regularly capable of firing 80-mph rockets at their opponent’s feet really does not need the ability to stretch like a contortionist while retrieving a backhand.

No one has absolute power on a tennis court, but Sabalenka is close. At Indian Wells, she played Madison Keys in the semifinal, who had upset her in the Australian Open final and had yet to lose in 2025. Sabalenka needed all of 51 minutes to exact gory revenge, 6-0, 6-1. In Miami, Sabalenka won 81 percent of the points played on Olympic gold medalist Qinwen Zheng’s second serve and 90 percent against Jessica Pegula’s second serve in the first set of their final. Even for top-class returners, these numbers are foreign and frightening. Sabalenka’s on-court presence is intimidating, and given the beatings she lays on opponents, it’s a testament to her personality that she has an easy rapport with many of her victims.

For a while, however, Sabalenka was primarily known as a choker. She grew iconic for losing in semifinals, hitting herself out of the last four at the 2021 U.S. Open semifinal with a quartet of unforced errors despite her opponent, Leylah Fernandez, being an underdog three days removed from her 19th birthday. In the 2022 U.S. Open semis, Sabalenka forged a 4-2 lead over Swiatek in a deciding third set and dropped the last four games in succession. That same year, Sabalenka’s serve rebelled so violently it looked impossible to make peace with. She sometimes hit as many as 20 double faults per match.

Even after Sabalenka won her first major at the 2023 Australian Open, which figured to provide cathartic relief, her yips persisted. One point away from a monumental Roland-Garros final with Swiatek, Sabalenka authored her most spectacular collapse yet against Karolina Muchova. At Wimbledon, she lost to Ons Jabeur in the semifinals from a set and a break up with huge underdog Marketa Vondrousova waiting in the final. The U.S. Open? After a dominant first set against Coco Gauff in the final, Sabalenka imploded once more.

The Sabalenka meltdown is a staple of the tennis fan’s experience. Overhead smashes thwack the net in places you wouldn’t believe a professional tennis player has hit since their first childhood brushes with the sport. Double faults string themselves together. Rallies end with wild attempts at a kill shot before they can properly begin. Rallies that do extend die suddenly with misses not even intended to do damage. Holding serve becomes impossible. The opponent stretches her game around the meltdown, abandoning her own offensive instincts to let the mistakes metastasize until the match is over. It’s why Sabalenka won one major in 2023 instead of a historically dominant three or four.

Other champions’ negotiations with their Achilles’ heels usually involve winning an internal battle of emotion. Sabalenka is unique in how often she loses that battle. She’s simply become such a good tennis player that the meltdowns no longer get the final say in her matches, like if Clayton Kershaw had dominated in the playoffs by learning how to throw a 115-mph fastball instead of just not throwing his first pitch to Juan Soto into the middle of the strike zone. For Sabalenka, the festival of errors on match point now comes when she has a 6-3, 5-2 lead more often than in a desperately close deciding set. She can’t silence her doubts, but her skill drowns them out.

Courtney Nguyen, a writer who has covered the WTA for over a decade, has spoken to Sabalenka after many of her biggest wins and most sapping defeats. “She’s a more well-rounded person now. She is more mature,” Nguyen said in an interview. “She’s softened the edges while retaining every ounce of that competitive fire. I think while those losses are rough and they probably hurt just as much as they hurt before, that window of how long that hangover lasts is so much shorter now than it was before.”

Sabalenka lacking the requisite mental strength to regularly consolidate her leads in finals is likely an oversimplification. Following a loss to Mirra Andreeva in the Indian Wells final, where she melted down in the third set, Sabalenka noted that Andreeva was gelling well with her coach, former Wimbledon champion Conchita Martinez. “In that age, I was surrounded by so many wrong people,” Sabalenka said in her press conference. “And finally when I was able to get rid of those people, and I surrounded myself with the right people, you have more confidence, everything is more calm, the atmosphere in the team is very healthy … [Andreeva] doesn’t have those abusive things.”

Sabalenka eventually assembled a successful team, but it took time and pain. In 2018, Sabalenka’s former coach Dmitry Tursunov told Nguyen that earlier in Sabalenka’s development, she had been told she was stupid and only capable of playing in a ballbashing style.

“There was a way for her to be a healthier person with respect to herself earlier, I think,” Nguyen said. “The way that she was coached, and the constant, very negative-minded manner in which she was coached … When you’re a young woman by yourself, that’s formative. It really makes you think that you’re not worth anything.”

Sabalenka will turn 27 in May. She might always be prone to implosion, but as long as she can crack winners of every variety imaginable, you have to wonder if she could and should reign over the tour for years to come.

“There’s ‘should’ and then there’s ‘will,’” Nguyen said. “By the end of her career, at the level that she’s playing, barring injury, she should be in double-digits majors-wise. She gets to those end stages, and it’s just whether she can close.”

Sabalenka closing more regularly is a tantalizing prospect, but it’s difficult to imagine, because she’s never been an ice-cold finisher. Sabalenka’s career is a story of hard-won success after an agonizing runway, not easy dominance. Her warts—the consecutive double faults at the tail end of a major semifinal, the overeager backhands right into the net’s broad clutches—are the most relatable thing about her tennis. They’re certainly more relatable than her ability to wipe the outside of the line with an inside-out forehand winner struck while backpedaling. The athletic transcendence is spectacular to watch, but the internal fractures help maintain a constant sense of drama and doubt. Her success is richer for it. Watching a player overcome their worst habits is always compelling, but there’s nothing more magnetic to a tennis fan than being so taken with the skill in front of your eyes that you can’t help but imagine the platonic ideal of that player mowing down everything in their path. Sabalenka lets you do both.