I do not know much about music. I had no music education. An ex-girlfriend told me my karaoke version of “Wonderwall” was the worst thing she’d ever heard. I cannot find the beat; my wife laughs at my attempts to dance. I was humming a song to our son the other day in an attempt to get him to fall asleep. “That’s not how it goes,” she said. I thought about it. She was right.

And so a lot of my musical taste has been shaped by others. As a preteen I followed the tastes of Joey down the street. In high school Tim made me realize how good Pearl Jam is live. Kristin taught me about Sleater-Kinney; she was the first of several girlfriends to inform me that Hole’s Pretty on the Inside outsold Nirvana’s Bleach until Nevermind came out. Philadelphia Weekly and City Paper introduced me to cool local bands.

Pitchfork filled in the gaps around all this. I discovered it in high school, a year or two after the site’s 1996 founding, and have been a reader ever since. I’d type pitchforkmedia.com into a web browser almost daily. Pitchfork introduced me to new bands and deepened my appreciation for groups I already liked. The amount of music I could discover felt limitless. I still check to see what Pitchfork thinks of my favorite artists and still learn about new music based on the site’s recommendations, but it's hard to know much longer that will be possible. Earlier this month Conde Nast told staff it was folding the site into the operations of GQ. Pitchfork is still publishing, but many staffers were laid off. “It feels safe to assume that it will become a smaller, dimmer version of what it was,” my colleague Israel Daramola wrote.

It's a shame. The site was, and is, so well designed. Old reviews were easily accessible. Click on a letter of the alphabet and you’d find tons of reviews to choose from. I liked the site’s tone, too; it was irreverent and snobby, which is a pretty good way to write about music. Pitchfork not only gave me bands to listen to, but told me how I might think about them. It told me how to pose, too. For a teenager who didn’t know much about music, this was crucial. It’s also true for an adult who still fits that descriptor.

But it wasn’t just posing. One review from Pitchfork influenced my musical tastes more than any other. It was a two-paragraph review of Moby’s I Like To Score, an album released on Oct. 10, 1997. I was 14. I might not have discovered this review until the following year, but I remember it for its ending, as baffling to me now as it was then. “If you still need an intro to techno, let Moby be your doorman,” it reads. “After all, he’s got no hair.”

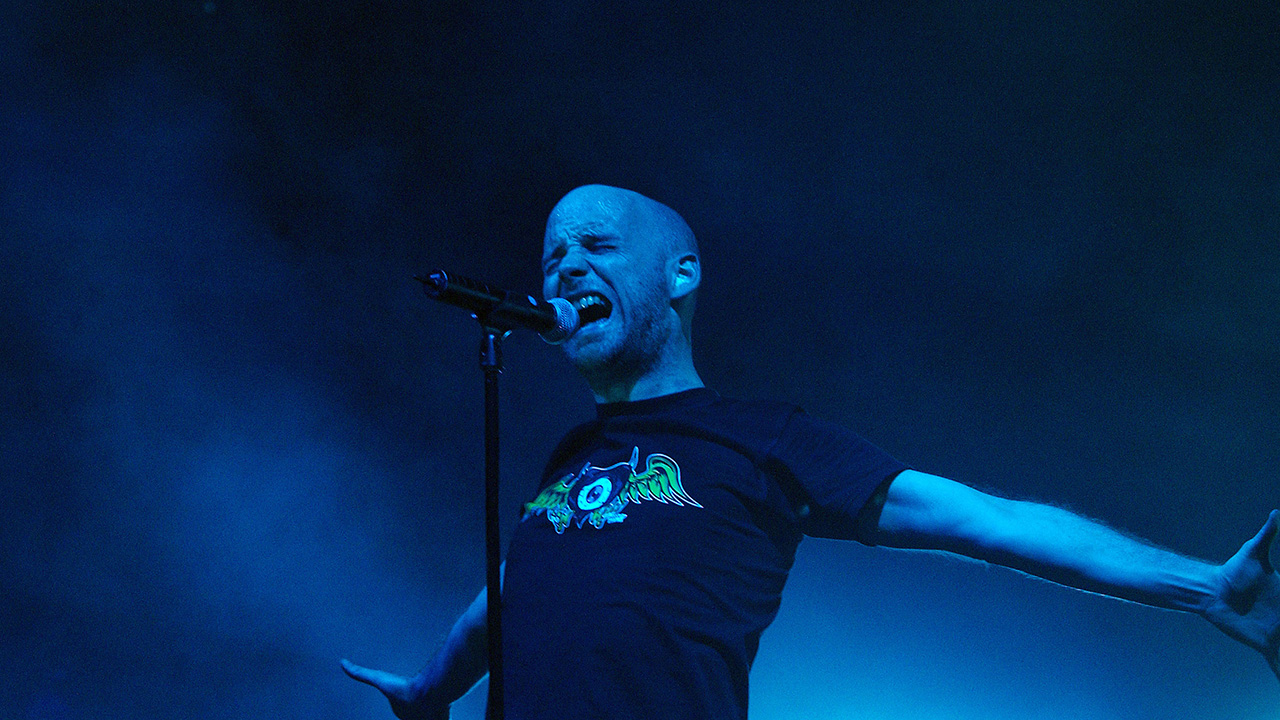

Despite that kicker, the review convinced me to buy that CD, a year or two before Moby’s breakthrough single “Bodyrock.” I agreed with the critic’s 8.6 score for the album. I began listening to more Moby, more techno made by other bald men, more techno in general. I revisited corny “Eurodance” music. I realized that it was not just a genre I liked as a preteen. In 2000 I discovered the original Ishkur’s Guide, and my lifelong fascination with electronic music was cemented. I still have the musical tastes of an Old Millennial who watched a lot of MTV and went to an all-boys Catholic high school: ’90s alt-rock and hip-hop, early-’00s indie rock, classic pop and rock bands of varying levels of embarrassment. But electronic music is what I listen to most. For the last decade or so it’s been synthwave and related genres. But I still listen to corny ’90s shit; I made them put on Jock Jams at a recent art show. I’ve grown to appreciate 1970s disco and funk music. Nine Inch Nails still ticks a lot of my boxes. I am listening to I Like To Score as I write this, and I still like it. The best track is “Go,” which is built around “Laura Palmer’s Theme” from Twin Peaks. The credited songwriters are Moby, Angelo Badalamenti, and David Lynch. It’s great.

James P. Wisdom wrote that review of I Like To Score. For someone who wrote almost all of his reviews before most people began reading the site, Wisdom remains one of its more reviled reviewers among people who have opinions about things like this. “That's when their cover of ‘Come On Eileen’ came on,” he wrote in his 9.5 review of Save Ferris’s It Means Everything. “I think I came. Great music that won't be soon forgotten by anyone who's heard them.”

There’s a 2005 I Love Music messageboard post titled “So, what is the worst music review ever then?” One poster, Brian Whitman, believed he had an answer. Whitman had recently published a paper with Daniel P.W. Ellis about album reviews. “‘Automatic Record Reviews’ was a very early (2004!) version of the AI madness we see all over today, trying to make sense of writing and music and how they’re connected, using a tiny fraction of the computing power and certainly none of the world-dominating goals, but very similar math,” Whitman told me over email. “I was driven by this at-the-time futuristic idea that all music would be available to anyone on demand, and we would need smart ways of discovering it.” Whitman’s metric attempted to rate the “objective quality” of reviews from All Music Guide and Pitchfork. It will come as no surprise that AMG’s reviews were much more likely to refer to the audio than Pitchfork’s. But the paper was agnostic on which type of review was better.

“I always joked about the very of-its-time personal ‘bloggy’ nature of 00s Pitchfork, the paragraphs of personal exposition before getting to the music,” Whitman tells me over email. “Posting that sorted list on ILM was my little rib to that group of writers. I still read and loved Pitchfork throughout its life. In retrospect, I feel that contextualizing and humanizing how we find and explore music is valuable, and it’s sad we’ve lost a lot of it.” He does have a personal connection to the site, too. An album by his brother, Keith Fullerton Whitman, received a 9.7 from the site in 2002. After one listen to Playthroughs, I am disappointed I did not find this review sooner.

Whitman posted Pitchfork’s 10 lowest-scoring reviews, per his algorithm. Wisdom wrote four: Juno Reactor’s Bible of Dreams (4.9), Stereolab’s Dots And Loops (8.5), Dr. Octagon’s Dr. Octagonecologyst (9.2), and Morcheeba’s Big Calm (6.7). Two other reviews were by Paul Cooper, and four by Brent DiCrescenzo. Coincidentally, one of DiCrescenzo’s reviews is of Swervedriver's 99th Dream (8.9). Stuart Berman reviewed the reissue earlier this month and gave it a 8.0.

The person who showed me the forum post about Pitchfork’s worst reviews was James P. Wisdom himself. I talked to him last week. He discovered the site in the 1990s while searching for information about the Sneaker Pimps’ debut album Becoming X. (That is the kind of thing people did in the ’90s.) Wisdom found a review on Pitchfork (6.3) written by site founder Ryan Schreiber and liked it. “The Sneakers are like an electrified version of Sade,” Schreiber wrote. “They’ve got that same kind of sexy glamour.”

“I liked it because it was irreverent, and snarky, and nerdy,” Wisdom says. “And then I looked through the rest of the site and read a ton of reviews. At that time they were running four reviews a day. Out of the blue, I messaged the editor, which was Ryan, and I said ‘I really liked your site. I want to write reviews.’ And he said OK.” This is the kind of thing that happened in the ’90s, too. Wisdom and I have this kind of experience in common: I emailed Al Isaacs of Scoops, a wrestling site, out of the blue around the same time. I ended up writing recaps of ECW’s weekly TV show until the site closed. The opportunities of the Internet seemed limitless to us, even if we both were just using them to write about things we liked.

Wisdom had a much longer stint as a 1990s critic than I did. After his email, he says Schreiber sent him a copy of the CD that would become his first review: MTV’s Amp, a compilation produced by the channel’s electronica/rave TV show of the same name. It featured some of the bigger electronic acts of the time: Chemical Brothers, Crystal Method, Aphex Twin, The Prodigy, Orbital. Wisdom gave it an 8.9, and became one of the site’s few reviewers. He eventually got the title of senior editor. “I’m not exactly sure why,” he says, “other than the fact that I could be relied upon to crank out reviews like a madman.”

Every week Wisdom would get a stack of CDs in the mail and was responsible for writing four reviews a week. Most are only a few paragraphs, but that’s understandable: He only had a day or two to listen to, think about, and review an album. He was not paid, but did make some money from selling the CDs to a record store after he was done with them. Again, this was a very ’90s thing to do.

Pitchfork is best known for being the home of indie rock, but a spin through its archives shows it actually covered an admirably wide swath of independent music in its early days. There are way more hip-hop reviews than I remembered; it must’ve been how I discovered Dälek (Negro, Necro, Nekros, 8.0). The site was also a champion for electronic music, and Wisdom did much of that work. It was not designed that way, really. Wisdom said he had some connections to the D.C. rave scene, as he was living in Southern Maryland at the time, but he didn’t have any background in it. “I think Ryan just liked sending me all the crap that he didn’t want to review,” he told me.

I didn’t realize that at the time, but Wisdom was the electronic critic music to me—and maybe others, too. He even got to interview Moby, in what he told me was the worst moment of his Pitchfork career. “I opened the interview and I asked him what socks he was wearing,” he says. “I just wanted to ask him something stupid, and not basic. And he immediately shut down, didn’t want to talk to me, and basically cut the interview short.”

Wisdom estimates he wrote about 400 reviews for the site during his time there. Most of his hundreds of reviews have been deleted, but there are still 14 of them on Pitchfork—from a 1999 review of Coldcut’s Let Us Replay (8.9) to a 2004 review of Tindersticks’ soundtrack to Claire Denis’s film Nenette Et Boni (7.9). Eventually Schreiber began sending CDs of MP3s—things Wisdom couldn’t sell. The site had more writers by then, and he eventually fell off. His time had run its course. Schreiber began deleting some older reviews. “He told me there were just too many reviews,” Wisdom says. “He just wanted to be able to make the site more manageable… back then I think it was literally thousands of reviews and he just didn’t want to deal with that volume anymore.” He understood. He didn’t always get his reviews years later, anyway. He is as baffled as I am about Moby being a bald doorman.

Though most of his reviews are gone, Wisdom’s legacy remains. For me, it’s his reviews of Moby and other electronic acts. Others remember different reviews, and less fondly. Though it’s deleted, that Save Ferris review lingers. “This was the review that has in many ways come to typify my tenure there,” Wisdom said, “because people were so pissed about it.” Wisdom is surely not alone among critics in having this experience as part of his legacy.

“People knew it wasn’t a 9.5,” he said. “And it wasn’t, in retrospect. And the people that cared about the ratings, and the reviews, could not let go of it. I’m not kidding you. I’ve been contacted by people in the last five years about this review. They’re that pissed off about it. I’ve had people tweet about it in 2017—literally 20 years after a two-paragraph review.” That is not the only old Pitchfork review that still pisses people off. This month there have been at least six tweets from people still angry, one written in Greek, about Pitchfork’s 1.9 review of Tool’s Lateralus. Some people still like Brent DiCrescenzo’s pan of the 2001 album, including at least one person who tweeted in Dutch: “pitchfork review van lateralus is een van de beste dingen ooit vooral vanwege de reactie van tool fans.” Hard to argue with that.

Wisdom could see the site’s growing influence in the number of emails he began getting. Besides Save Ferris, the other review that got him a bunch of letters was of Kottonmouth Kings’ Royal Highness (1.9). Fans put down their bongs long enough to write him angry emails about a review that opens: “It's a shame how they let any old dope smoker put out records nowadays. Back in the day, they used to issue permits for such things.” I think this judgment holds up quite a bit better.

Many have commented at Pitchfork’s turn toward “poptimism”—broadly, the idea that pop music is as worthy as any other genre—as the moment when the site lost its way. This is just a Medium post quoting someone on Reddit, but it is a good example of the argument: “[Pitchfork’s] narratives for bands and records used to be based solely on their own merit but now they are dissected and judged based on how they fit into the current cultural climate. It’s a damn shame.”

I get this argument, which you can find in many places. I agree that a Pitchfork list that says Pavement’s “Gold Soundz” is the best song of the ’90s is a much more interesting version than one that puts Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy (Remix)” featuring Ol’ Dirty Bastard at No. 1, and I say this even though I think “Fantasy (Remix)” is a better tune. While still reviewing heaps of indie music, Pitchfork has certainly expanded what they cover. The site's 2021 review rescoring was, I think, mean to past contributors, but so many of the anguished arguments against it seemed to miss the mark for me. I shall be a pompous ground-floor Pitchfork reader here: Those people are posturing, too. And they do not get it. Pitchfork reviews have always been just as much about where and how music fits in the culture as they have been about the music itself. The culture has changed, and so the type of posturing changes too. But the Pitchfork ethos has remained steady in the most important ways.

Take Wisdom’s Save Ferris review. “We used it as a soundtrack for a giant house party that I had at the time, where there was a lot of drinking and drug use going on,” he says. “And we had a good time with it. It was a great soundtrack for that particular moment, where nobody gave a shit and people were just hanging out and partying. For me in that moment, it was a 9.5.” He says now he’d give it “a 4.2 or something like that.”

His 8.5 review of Stereolab is a made-up story about being in a sensory deprivation tank at Rutgers and believing he'd spent “three days in the Amsterdam of 1951.” It has absolutely nothing to do with Stereolab. “Ryan liked that type of thing,” he says. “I would send him these reviews that were like this, and sometimes he called me to be like, ‘This is not even about the album. You have to put something in.’”

Conde Nast folding Pitchfork into GQ is a bummer. Even if it continues in some diminished form, the site will be worse off for it; it is now difficult to imagine its ethos surviving this sort of move. A lot of people were laid off. But what feels worse, in the days since, has been the sense that there doesn’t seem to be many of those jobs left, for these critics or anyone else. Pitchfork was old, with roots that date back to what feels like the beginning of the usable internet. The site had been around since the 1990s. Al Isaacs closed Scoops, the wrestling site I wrote for, more than 25 years ago; Pitchfork continued, and a lot of people got to write about things they cared about there. Even if a lot of the site was about posturing, the jobs there seemed honest.

Whitman, the academic who reviewed the site’s album reviews algorithmically, still checks in monthly to see if there’s anything he missed. “It’s definitely in that ‘old internet’ bucket for me—a place for fans of something, not owned by one of the big internet platforms, with professionals writing editorially independent text about something I care about,” he writes. “It’s also refreshingly something you have to seek out, type the domain name in your browser, instead of running across it in a feed with no control. How much more of that will we get?”

One more thing. After our interview, Wisdom emailed me. He wanted to write one more review, and I thought it’d be nice to publish it. And so here it is: Defector Media presents James P. Wisdom’s final Pitchfork Media-style review:

![Kid KoalaScratchcratchratchatch[Ninja Tune]Rating: 10.0I saw Kid Koala play in Hoboken around 2000 for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. I'd been hearing—and loving—him on the Ninja Tune comp discs of that era and somehow heard about this demo tape that was only sold at shows. So after the tiny, sweaty, poorly-attended Hoboken show I bought the last two of the tapes. At the time the scuttlebutt was that he couldn't sell the tapes thru stores because none of the samples were cleared. These tapes were perhaps my most treasured musical possession at the time and I bought a crappy Radio Shack cable to transfer the tape to digital so I could share it with my friends using a P2P program called Qnext. Everyone loved it. And so do I. Then. Now. Always.It's a mad scratch pastiche that for me, really represents the pinnacle of this genre. It's all hopeful, playful, silly, stupid, skilled, masterful, fun.](https://lede-admin.defector.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2024/01/defector-pitchfork-wisdom-review.png?w=710)