Earlier this year, on a cold Sunday in January, I walked into an antique store in a Washington, D.C. suburb. When I go to a shop like this one, I'm not looking for chairs or lamps. My interests are a little more specialized: a collectible whiskey decanter shaped like the Superdome, for instance, or a 1976 tabloid spread about Watergate witnesses who died under strange circumstances.

Now I was on the lookout for other important historical artifacts. And this place, West Howard Antiques in Kensington, Md., had a ton of them: sports yearbooks, posters, and all kinds of political ephemera, stuff with slogans like "Youth for Kennedy" and "Jimmy Carter 76."

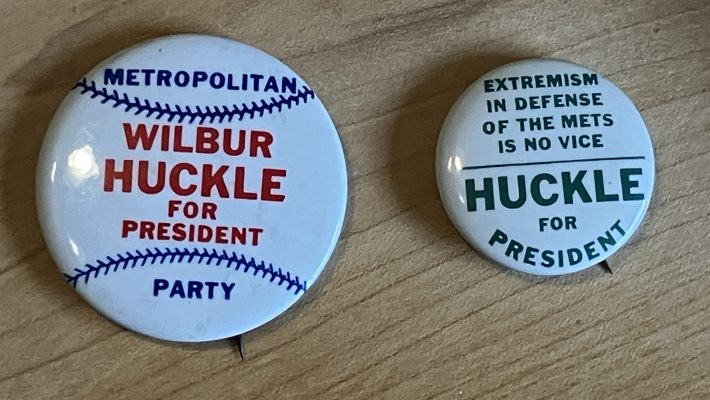

And then, sitting on a plastic stand, I saw a small button, one-and-a-quarter inches in diameter, with green text on a white background. It said: "Extremism in Defense of the Mets Is No Vice." Now this was enticing.

The New York Mets have been my favorite baseball team since I was six years old and I saw them at the top of the standings in the sports page of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. That was 1986, one of two years in the last 63 when becoming a Mets fan might've felt like a wise decision.

Regardless, I stuck with it and steeped myself in Mets lore—Choo-Choo Coleman and Elio Chacón and "Ya Gotta Believe!" But this "extremism" slogan was a total mystery to me. Plus, there were three more words, laid out across the bottom of the button, that were just as inscrutable: "Huckle for President."

That Sunday, I bought the button for $12.50, took it home, and got to work. I wanted to figure out why this weird button existed. Who came up with these slogans? Who put them on a souvenir? And who in the heck was Huckle?

This story was adapted from the pilot episode of the sports history podcast Replay Booth. You can listen to the audio version here.

Like me, Mitch Stephens was six years old when his favorite team won the World Series. That victory by the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers should've cemented a lifetime of fandom. But a couple years later, team owner Walter O'Malley set his sights on Los Angeles. Stephens was bereft. He even resorted to rooting for the Yankees, but Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris didn't quite fill the void.

Then, in 1962, the New York Mets came to town. "Here was this new thing—this team that was ours," Stephens says. It didn't even matter that the Mets lost 120 games in their first season. "I've rooted for a lot of terrible teams in my life, but the Mets were the most fun terrible team to root for[.]"

The main source of that fun was Mets fans themselves. "They are a strange, wonderful people, this 'new breed,'" Dick Young wrote in the New York Daily News on April 16, 1962. That nickname caught on, and eventually got capitalized and added to the Dickson Baseball Dictionary. The New Breed were "rabid" and "anti-authoritarian." They were also known for pioneering a new method of self-expression: topical, handmade banners—Mets manager Casey Stengel called them "placards"—painted on bedsheets and brought to the ballpark.

This was the start of a new era of participatory fandom. Long before blogs and social media, and as call-in sports radio was just emerging, the New Breed's signs were a medium for honest, real-time commentary. While the players bumbled on the field, the fans brought banners reading "Ninth Place or Bust" and "Know Why the Mets Are Such Good Losers?—Practice Makes Perfect."

Mitch Stephens and his high school classmates were prolific sloganeers. Stephens's favorite contribution was "Will Success Spoil Rod Kanehl?", a take-off on the 1957 film Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? ("The joke was, he wasn't all that successful," Stephens says. Though he hit the first grand slam in franchise history as a 28-year-old rookie, Kanehl posted a negative WAR in each of his three seasons in MLB.)

But the group’s biggest success came from the mind of one of Stephens's friends: "Is Ed Kranepool Over the Hill?" When they came up with that one, Kranepool was all of 19 years old. Although the Mets' first baseman said he didn't get the joke, the beat writers thought it was hilarious. "It's probably the most referred-to banner in, I would say, baseball history," Stephens says.

While the stodgy cross-town Yankees made it their policy to confiscate fan-made banners, the Mets embraced this new grassroots culture. In 1963, the franchise launched an annual on-field contest and celebration: Banner Day. The big winner that first year was a banner reading "This Sign Is in Favor of the Mets." The 18-year-old who came up with it told reporters, "Everybody said it was a silly idea, so I made it."

When Banner Day came around again the next year, Mitch Stephens and his friends were in it to win it. Their search for the perfect Mets slogan would draw their attention far from Flushing.

Going into the 1964 Republican National Convention in Daly City, Calif., in July, the party still hadn't decided on a presidential nominee. The leading contender was conservative Barry Goldwater, but the GOP had a vocal #NeverGoldwater contingent. One of its leading spokesmen was long-time Republican Jackie Robinson, who was appalled by the Arizona senator's "no" vote on the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Goldwater claimed that this sweeping anti-discrimination legislation violated states' rights. But to Robinson and plenty of others, that argument felt like a naked appeal to bigotry. "This is a calculated campaign against minorities," Robinson told CBS before the convention. "In my view, any party that would nominate a man to run on this particular platform is jeopardizing the prestige of Americans throughout this world."

Robinson's preferred Republican candidate was New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who used his convention speech to advocate for keeping "the Republican Party the party of all the people." That note of reconciliation drew some polite cheers. But when Rockefeller denounced the party’s "extremist" right wing, the crowd started chanting, "We want Barry!"

The next night, Goldwater locked up the Republican nomination. In his victory speech, he told his supporters what they wanted to hear: "I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice."

When the cheering finally died down 40 seconds later, Goldwater added a second line: "Moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue." But it was the first half of the quip that caught the nation's attention.

"Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice" was Goldwater's way of defending his conservative views. It was also a call to push the whole Republican Party further to the right. Goldwater's words marked the beginning of a new political age, one we're still living in. In 1964, white Southern Democrats started migrating to the Republican Party, and black voters, including Jackie Robinson, began to move en masse to the Democratic side.

Back on Long Island, the teenage Mitch Stephens was a devoted Democrat and no fan of Barry Goldwater. Stephens says that his politics and his baseball fandom also felt very connected: "Everything about the Democratic Party said youthful at that moment, and the Mets were new and young, and felt like they were kind of for the young."

After the Republican Convention, Stephens and his high school classmates had their slogan for Banner Day: "Extremism in Defense of the Mets Is No Vice."

His friend Ben Ross, the guy who'd come up with "Is Ed Kranepool Over the Hill?", was the brains behind this slogan, too. The whole group loved it right away. "We were pretty extreme, but I think the main purpose of the banner was to mock Goldwater," Stephens says.

Four of them painted the sign in Stephens's parents' driveway, though there's some dispute within the group about whether they slathered the slogan on a bedsheet or a shower curtain liner. Either way, they were all ready to go for Banner Day at Shea Stadium, on Aug. 23, 1964. Or, at least three of them were: Ross had to spend time at his aunt's house, so Stephens's friend Arthur Engoron came along to help hold the sign.

The Mets had a doubleheader that Sunday, and the parade of banners took place between games. On the radio broadcast, Mets announcer Ralph Kiner describes the "mighty colorful picture" of more than a thousand banners strewn across the field. Stephens remembers feeling like the area around home plate was center stage, and making an extra effort to make sure their handiwork was visible to the judges. Engoron says that when they reached the end of the procession, someone shouted, "Hey, yeah, it's them! Get them out of the line!"

They won the grand prize at Banner Day—portable TV sets donated by Macy's—and got celebrated by name in the New York papers, with Newsday's Stan Isaacs writing, "these young men have a particular talent for signs." Sixty-one years later, they still remember how they felt that Sunday in 1964.

"It was a type of excitement that I've experienced very rarely in my life—maybe at my wedding, to some extent," Stephens says.

"I remember thinking, Wow, if you're reasonably clever and you're in the right place at the right time, exciting things could happen in your life. And they have," says Engoron.

Mitch Stephens went on to become an author and a journalism professor. Arthur Engoron is a judge. A few years ago, he found himself presiding over a civil fraud case in New York State Supreme Court—a case in which, as the New York Times put it, the state's attorney general Letitia James "put [Donald] Trump's fantastical claims of wealth on trial."

In February 2024, Judge Engoron ordered Trump to pay a penalty of $355 million plus interest for committing financial fraud. His ruling included a line that, with a little adaptation, might have looked good on a Mets banner. He said, of Trump and his co-defendants, that "their complete lack of contrition and remorse borders on pathological."

Trump called Engoron a "crooked judge." Engoron was subjected to a hoax bomb threat at his house. Then, earlier this year, a New York appeals court threw out that $355 million fine, calling it "excessive." The case is still ongoing, but the 76-year-old Judge Engoron will be leaving the bench at the end of this year after reaching New York's mandatory retirement age.

In our interview, he told me he couldn't talk about anything political. But he did say that the judges at Banner Day in 1964 had reached the correct verdict: "I think they showed a certain sophistication and a certain appreciation of a certain type of humor."

As far as the button I'd found at an antique store—the one that said "Extremism in Defense of the Mets Is No Vice" above "Huckle for President"—neither Stephens or Engoron had ever seen it before, and neither of them had heard of this mysterious Huckle. But I found some other people who had.

Ron Swoboda was grateful to sign a contract with anyone in pro baseball. But in the early 1960s, the New York Mets had a special appeal. They "were the best chance to get to the big leagues the fastest," he says, "because they were the worst team in big-league baseball."

Swoboda's first chance to impress came at a special instructional camp in 1964. That February in Florida, he practiced, played exhibition games, and met his new teammates. One of them was a young shortstop.

"Wilbur Huckle was a Texan, sort of red hair, freckles—great-looking guy," Swoboda says. He got to study Huckle more closely that spring, when the Mets sent them both to the team's minor-league affiliate in Williamsport, Penn. "He was a smart kid and played hard, and he played shortstop back when they came down there trying to take your ass out," Swoboda says.

Rod Gaspar, who joined the Mets organization a few years later, was impressed too. He says Huckle did "different things that no other ball players did. Say he's in a rundown—he'd intentionally get hit by the ball." He remembers Huckle being a man of few words but plenty of emotions: "He'd get fired up more than anybody I've ever seen. I could get pretty fired up on the field, but nobody was like Wilbur."

There was one more thing that both Swoboda and Gaspar wanted to tell me. It was about their old teammate's post-game routine.

"When the game was over, I never saw anybody as fast as Wilbur Huckle getting in and out of the shower, into his clothes, and out of there as fast as he could," Swoboda says.

"By the time we're all getting in, getting undressed, Wilbur was gone," says Gaspar. "As to where he went, I have no idea, but he took off."

It wasn't just Swoboda and Gaspar who found Huckle fascinating. Mets legend Tom Seaver, who died in 2020, roomed with Huckle in the minors. In his autobiography, Seaver said: "I never saw Wilbur Huckle in our room—at least not awake. I never talked with him. I never heard him. When I came in at night, early or late, he was either out or asleep. And when I got up in the morning, he was always gone."

But what about that slogan, "Huckle for President"? It would take a devoted Mets fan to unlock that piece of the mystery.

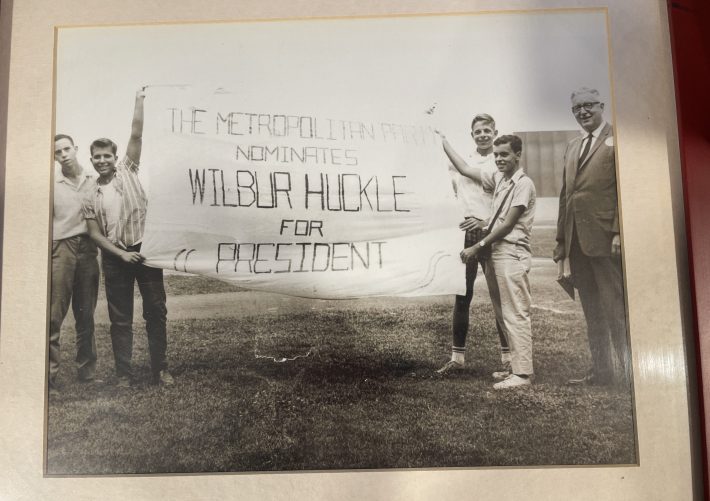

Ronald Einziger grew up in Manhattan, and like Mitch Stephens and Arthur Engoron he wanted to win the 1964 New York Mets Banner Day contest. "I was just talking with a bunch of my friends in high school, and we decided on 'The Metropolitan Party Nominates Wilbur Huckle for President,'" he says.

Just like the "extremism" slogan, the "Metropolitan Party" bit was a hook into the 1964 presidential election. But Wilbur Huckle? Einziger had never actually seen him play. All he knew was that Huckle was a top shortstop prospect in the minor leagues. In that moment, when the New York Mets were the worst team in baseball, Huckle represented hope for the future—a time when the roster would be loaded with talent, and the Mets might actually win some games.

Plus, Einziger just liked the guy's name. "Huckle, like Huckleberry Finn, Huckleberry Hound. And Wilbur just sounds like a very rural name."

Einziger and his friends painted up a bedsheet, and on Banner Day they paraded their sign around Shea Stadium. They won prizes that day, too—plaques and transistor radios—and got their photo taken. In that picture, which Einziger still has, he's standing alongside his banner, looking incredibly proud of what he's created. And he's still proud, six decades later.

Einziger is a lawyer, and a while back he found himself telling a colleague the story of Banner Day. "And he asked me, so whatever became of Wilbur Huckle? And I said, 'I don't know.' So that night, I went home and googled him, and I saw somebody selling that button."

By the time I spoke with Einziger, I'd done some googling myself, and I'd discovered that there were actually two buttons: the small one I'd bought, and one that was a little bigger and styled like a baseball. That one said, "Metropolitan Party | Wilbur Huckle for President."

Einziger says that when he saw that, he started screaming, "That bastard stole my slogan!" The trouble was, he had no idea who "that bastard" was.

Just like Mitch Stephens and Arthur Engoron, Ronald Einziger had nothing to do with the buttons. To figure out who did, I reached out to Christen Carter, the owner of Busy Beaver Buttons & Merch and the president and co-curator of The Button Museum in Chicago. The "Extremism | Huckle for President" button is part of the museum's permanent collection.

Carter says that button is an early '60s classic. The text was letter-press printed on paper, then covered with a plastic coating and secured onto a metal disk, with a metal rim on the back for stability. It's known as a pinback button because, well, there's a pin on the back, to make it easy to wear your favorite message or to support your favorite candidate.

The 1964 presidential election was a big one button-wise. Barry Goldwater may have lost to Lyndon Johnson in a landslide, but his pinback game was on point. There was "In Your Heart You Know He's Right," with his smiling face smack in the middle of a big red heart. There was also "AuH2O," the chemical symbols for gold and water.

Those buttons didn't go unchallenged. Democrats had their own pin with Goldwater's face and the slogan: "In Your Guts You Know He's Nuts." There was also a button reading "C5H4N4O3 on AuH2O.” C5H4N4O3 is the chemical formula for uric acid. "So it's basically saying piss on Goldwater," Carter says.

That Goldwater piss button has the insignia of Underground Uplift Unlimited, a counterculture shop in New York's Greenwich Village. The provenance of the Huckle buttons is tricker, because they don't have any markings to indicate who made them. But one of Carter's button-world contacts—David Lindeman from the auction house Anderson Americana—knew the origin story. These buttons, he told me, were the work of the A.G. Trimble Company.

That company's founder, Arthur Garfield Trimble, is a button legend—one of several people who claimed to have invented history's best-known presidential slogan: "I Like Ike." I’m not sure if A.G. Trimble himself created the Huckle buttons, or if someone commissioned him to do it. But what I do know is that when Trimble got out of the button business decades ago, Anderson Americana bought up their old inventory. That stash included a couple of sandwich bags full of both versions of the Wilbur Huckle button, about 50 pins in total.

I now knew where the slogans came from, what they meant, and who slapped them onto souvenirs. The only thing I had left to do was track down the man at the center of it all.

One of the first things I learned when I spoke to Wilbur Huckle was that his friends don't call him Wilbur. "No, they call me Wil," he told me over the phone. "But my wife calls me Mr. Huckle." He laughed, then confessed that wasn't true: "She just calls me Huckle."

Wil Huckle is 83 and he's been married for 61 years. He and his wife live on a ranch in Cross Cut, Texas; he says the town's population is "about 14." When I called him a couple weeks ago, he was underneath his Ford truck, trying to fix the "death wobble."

Huckle told me that eight decades back, as a kid in San Antonio in the 1940s, he always stood out thanks to his freckles and red hair. "There weren't too many redheads around, and so if you did anything wrong, they'd say, Well, it was that redhead, so you knew you'd better keep yourself straight."

Growing up, he played every kind of baseball there was: Little League, Pony League, Colt League, American Legion. No matter where he suited up, he was always a star. In high school, he made the all-state team at shortstop. The quote under his yearbook photo was "Major leagues, here I come."

In 1963, after three years in college at Sul Ross State, he got the offer he'd been hoping for: A scout for the New York Mets—Red Murff, who a year later would discover Nolan Ryan—told Huckle he'd give him $5,000 to turn pro. Wanting to be a savvy negotiator, he said he'd need to think it over. "So I come back the next day, [and Murff] said, 'OK. Now it's only worth $3,000 to you instead of five.' So I signed a contract, bought me a '63 Ford, and I went to Raleigh, North Carolina."

Huckle played for the Mets' Single-A affiliate in Raleigh, and was an immediate sensation. At 21 years old, he made the Carolina League All-Star Game and got some votes for rookie of the year, finishing just behind future legends Lou Piniella and Joe Morgan. Huckle's manager called him a major league–caliber shortstop, and bragged that he had bigger arms than the strapping slugger Gil Hodges. "I met Gil Hodges and I never did the comparison, but maybe so," he says. "Some people, because of my forearms, they call me Popeye."

As Huckle's reputation grew, Mets fans started demanding that he get called up to the majors, to infuse the last-place club with some desperately needed talent. Two fans even wrote a letter to the New York Daily News suggesting a new Mets rallying cry: "Our infield defense will never buckle, if our shortstop's name is Wilbur Huckle!"

The fans would get what they wanted: In September of 1963, after just three months of pro ball, Wil Huckle got called up to New York. Back then, the Mets still played at the Polo Grounds, and Huckle got the thrill of meeting Duke Snider, Willie Mays, and Willie McCovey.

Given that the Mets were deep in last place, Huckle figured that it was just a matter of time before he'd get a shot to take the field. But game after game, Casey Stengel kept him on the bench. After about a week, he asked the Mets' manager if he was ever going to get to play. Stengel’s response: "No, kid. You don't have any experience."

"So that was something to think over," Huckle says.

Although he'd believed he was going to get in the lineup, Huckle never actually got added to the Mets' official roster that September. Even so, he was still at the beginning of what looked like a promising career. The next year, 1964, he made another minor-league all-star team. The papers said he was a line-drive hitter and a "classy bunter," and that he was "held in high regard by the Mets' brass." He also made a big impression on his teammates, who admired his aggressiveness and his intensity. But they were truly obsessed with his high-speed post-game showers.

"I was the first one to the ballpark, and I was the first one to leave," Huckle told me when I asked about his showering routine. "You got there early and got extra batting practice and fielding practice. When the game was over, well, it was over. I didn't see any sense in sticking around. You know, what else were you going to do?"

There was at least one time when his fast showering got him into trouble with his manager. "That was Kerby Farrell," he says. "We had lost about oh, 10, 12 games in a row, I guess, and everybody was laughing and having a good time after the game. … And Kerby said, 'All right, that's it—nobody showers!' And about that time I was coming out and drying off."

I also asked about what Tom Seaver had said in his autobiography: "I never saw Wilbur Huckle in our room—at least not awake." He laughed, said that Seaver was a "quality individual," and explained, "Well, I'd get up early and go out and visit the sporting goods stores and Tom would sleep late."

And what would he do at the sporting goods stores?

"Oh, just look at the fishing gear and hunting gear and baseball stuff that was available. It just intrigued me."

Huckle and his minor-league teammates all had the same goal. Ron Swoboda made it to the big leagues in 1965, Tom Seaver in '67, and Rod Gaspar in '69. All three of them were members of the '69 Miracle Mets, one of the most heralded teams of all time and a group that Swoboda calls "a band of brothers."

Wil Huckle never got to be a part of that brotherhood. He didn't get called up in 1964, and in '65 his batting average dipped to .233. By 1966, a writer for Newsday was saying that Huckle "may never get a look." In the end, he didn't get any closer to the majors than he had in September 1963, when he sat on the bench and never cracked the lineup.

I'm not sure why Huckle never got a shot, but he believes his military obligations could've worked against him. He served in the Texas National Guard and would regularly get pulled away for duty. He says the effect on his baseball career was "devastating."

By 1970, Huckle's playing days were winding down. That year, when he was 28, the Mets asked him to be a player-coach, which he saw as a "kiss of death." Huckle, who eventually became a full-time minor-league manager, was a part of the Mets organization until 1974. That's when he and his wife "decided we got tired of living out of a suitcase, and so we came on home."

Back in Texas, he worked as a middle-school biology teacher, a school bus driver, and a coach. In a comment thread on Facebook a couple years ago, his students said that he was "the best science teacher ever" and "one of the nicest guys you will ever meet in your life."

Huckle built a baseball field on his ranch, and to this day he gives free baseball lessons to anyone who asks. His two daughters have also taken an interest in his pro career. A few years back, they discovered that someone had made buttons with their father's name on them, and they bought a handful of them online.

Huckle found all of this mystifying. During his playing days, and for decades after, he'd never heard about "Wilbur Huckle for President."

On the phone, I told him all about the banner contest, and that a kid named Ronald Einziger had put his name on a sign. When I asked what he thought about people making those banners and buttons, he told me, "Well, I appreciate them, and I just hope that they're still thinking about baseball—it's just such a great game."

The start of a game or a career is about possibility—the feeling that anything can happen. That moment is ephemeral. The ultimate outcome, whatever it is, gets written in ink: Somebody wins, somebody loses, somebody becomes a middle-school biology teacher.

But whenever I look at those "Huckle for President" buttons, I'm still living in that moment of possibility. It's September 1963, and a red-haired Texan is sitting in the Mets' dugout, asking the manager if he'll ever get to play. And maybe this time, Casey Stengel will tell him to head out to shortstop and show what he can do.