After Marcus Walden was called up by the Toronto Blue Jays in early 2014, nearly seven years after being drafted by the club, everything went more or less as you might expect for a big league promotion. For Father’s Day, Walden gifted his dad the first jersey he ever wore on a big league field; in his hometown of Fresno, Calif., his spot in history was solidified. “After 2014, when I came home, they put up a sign at my high school, number 67,” Walden told Defector. “And at my college, they have a wall with every guy who made it to the big leagues out of Fresno [City College], and I was put up there.” This is how it is supposed to go, and the congratulations and honors that are supposed to be bestowed on a player whose dream is coming true. “It was great,” Walden said, “except the issue was I never played.”

In the history recognized by Major League Baseball through to the moment this story is published, 23,522 players have been called up to the highest level of play and participated in at least one game for their team. A little bit deeper in the annals of baseball history, unrecognized by Baseball-Reference, FanGraphs, or Major League Baseball itself are the hundreds of players who were called up to the majors, wore their team’s uniform, had their names written on the lineup card, brought their families to the stadium, and spent at least one full game as an active player on the roster. The one catch, in this case, is that these players were never put into a game before being sent back down to the minors. Because of this, their status as a major leaguer exists in an odd in-between, a limbo of conflicting emotions and almosts. These phantom ballplayers made it to the pinnacle of the sport, but not quite across the threshold.

Do you feel like a big leaguer if you’ve put on the uniform but never made it into a game? “It’s one of those—not touchy, but weird ones where it feels like yes, but it also feels like no,” says Ryan Bollinger from his home in Germany, where he plays for the Haar Disciples. “I’ve been asked that a few times.” Twice during the 2018 season, Bollinger was called up to the New York Yankees and lived a day in the life of a big leaguer, and twice he was sent back down the next day without having appeared in a game. “I’d probably phrase it if someone came up and asked me, like, I made it up, but never got to play. I would consider myself a big leaguer in the loosest of terms.”

For players like Bollinger and others who are still active, defining oneself as a big leaguer is still an active process of sorts. Parker Bugg, currently pitching for the York Revolution of the Atlantic League, was on the taxi squad for Miami at a few points during the 2022 season, along with being called up for two days in August. “You know, literally, yeah I was on the active roster, I was in the bullpen ready to go if my name got called,” he told me. “But it’s still hard. It’s hard for me to consider myself a Major League player.” Upon returning to Triple-A, his pitching coach made a point of reminding him that he was in the majors, and that having made it there couldn’t be taken away even if he hadn’t made it into a game. “Deep down, I disagreed,” Bugg said. “I know they weren’t just saying it, but it’s like I didn’t quite feel it the same way.”

Once their professional careers disappear more fully behind them, some players said that they came to view their time up as the culmination of a lifetime of work, even if the official record doesn’t list it as such. Mike Antonini played 13 seasons of professional baseball across every level of the minors and two independent leagues. Much like Bollinger, Antonini was called up to the majors twice, both times by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the spring of 2012. “Yeah, definitely.” Antonini answered when asked if he would define himself as a Major Leaguer. “Just through the work that I put in and countless hours of training and spring games, minor league games, having that chance to be called up two separate times—I take credit for that. I know I don’t get anything recorded, but I take pride in considering myself a Major League player.”

In writing this story and talking to these players, I found myself questioning my own definition of what a Major League player is. The easiest answer, and perhaps the correct one, is just what the name implies: guys who played a game in the Major Leagues. But the more stories I heard from “phantom players,” and the others I found online, made me more willing to consider that maybe Major League Baseball’s definition wasn’t bulletproof. Or maybe it just wasn’t quite broad enough.

Larry Yount, the older brother of Hall of Famer Robin Yount, is the 13,196th player in Major League Baseball history. During his time on the Houston Astros’ roster in 1971, Yount pitched in a single game, but did not retire a batter or face a batter. During his warmup tosses, Yount hurt his elbow; he was removed from the game before throwing an actual pitch, but that happened after he was announced as the pitcher. Yount would battle injuries and ineffectiveness for the rest of his career, and never made it back to the bigs. His big league record exists, but contains no more action than, say, Parker Bugg’s: zero innings pitched, zero batters faced. None of this is to say Larry Yount shouldn’t count as a big leaguer—he is one. But the only things standing between Yount and the phantom ballplayers I interviewed for this story are something like 30 seconds and a handful of warm-up tosses on a mound between innings.

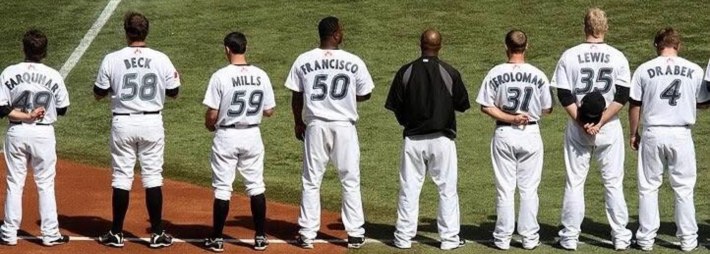

On the other side of the coin is a catcher by the name of Brian Jeroloman, a phantom player who was called up by the Toronto Blue Jays in 2011 and spent 37 days with the big league club. Despite having injured his wrist in his final appearance in the minors before being called up, Jeroloman wasn’t placed on the Jays’ injured list. He remained on the active roster for the entire five remaining weeks of the season, unable to play but officially both active and a Toronto Blue Jay. “We’d go out for breakfast together, go out to dinner together, play cards on the flights, I was in every way a part of the team.” Jeroloman, now Florida International University’s hitting coach, said of his time as the Blue Jays’ third catcher. From Aug. 23, 2011 until the final pitch of that season on the afternoon of Sept. 28, Brian Jeroloman lived the life of a Major Leaguer. Despite this, by the book, he never was one.

For Jeroloman, defining himself and his experience was an easy task. “If a guy spends his entire career in rookie ball except for one day where he was called up to Triple-A as an emergency arm, without pitching, he’s always gonna say he made it to Triple-A,” he told me. “If you put on a big league uniform and you’re in a big league stadium on an active roster wearing that uniform, you 100 percent made it to the big leagues.”

I’m not qualified to be the official arbiter of who is and isn’t a big leaguer; it wouldn’t be a job I’d want, even if I were. The only thing you can do is to look at Larry Yount, or Brian Jeroloman, or any other phantom player mentioned, and ask yourself whether or why some warmup pitches would completely alter your sense of whether a person achieved their dream or not.

For players who get called up, being sent back down without playing isn’t the end of their careers; in some cases it’s barely the midway point. Banked motivation is the coin of the realm for ballplayers, and it is tough to imagine a better incentive to get back to the big leagues than feeling as if something was left undone up there. Parker Bugg has played for four Atlantic League teams over the past three seasons and is still playing despite, by his estimation, pitching below full strength for all but a few weeks in that time. He remained despite, by his estimation, pitching below full strength for all but a few weeks in that time.

“If I’m honest, it still stings for me,” he said. “And maybe when my career is done a few years down the road, I can look back and say being called up was a bigger representation of the journey from when I was a little kid. Right now, there’s still that bit of fire in me that wants to beat the odds and get back up there.”

Mike Antonini went through similar circumstances in his years trying to make it back to the bigs. After he was called up until 2017, he dealt with a stress fracture in the back of his elbow. Following the surgery, Antonini switched roles, going from a starter to the back end of the bullpen. “As a starter, I knew how important [that] job was,” he said. “I want to get this guy his win, it wasn’t even about getting a save for myself.”

In the seven years following his promotions until his retirement following a 2019-2020 Puerto Rican Winter League championship with Cangrejeros de Santurce, Antonini played for four independent league teams, in the minors with the Angels, and spent four different winters pitching in Central America. Through it all, one thing stayed consistent. “The fire, I like to call it, that’s the daily competitive nature in the back of your head. You’ll do it all for that one more opportunity.”

Ryan Bollinger is currently playing for the same teams today as he was when the Yankees signed him out of Australia prior to the 2018 season. The summer before, he was starting for the German Baseball League with the Haar Disciples; in the winter he pitched for the Brisbane Bandits of the Australian Baseball League. Today, Bollinger is in the top 10 all time in ABL’s record books for strikeouts; as of this moment he’s leading all of Germany in strikeouts having already set the single-season record in 2017. “With the path I ended up taking, it was a kind of ‘Holy shit, this is happening to me’ kind of thing,” he remembered. “I had almost given up on that dream of making it.” After three seasons in the White Sox system, Bollinger spent three and a half years out of affiliated ball and traveling the world before catching on with the Yankees; today, he is happy in Germany and proud of his time in the bigs.

“I’ll play wherever the game takes me,” he says. “And just to have that opportunity feels better now than it did at the time because there were so many question marks. Like, ‘What happens if I get into one of those games? What happens if I do well in those games?’ I still ask myself that today and, I mean, maybe stupidly am still pushing to get to that point, you know? I tell the kids I play with that if you have a jersey you have a chance, and I’ll be waiting if I get it.”

Returning to the major leagues years after the first cameo and actually making a debut in the record book is a bit of a long shot, but it has happened. Daniel Camarena, who hit a grand slam off Max Scherzer in 2021, took nearly two years to get back to the majors after he first put on a uniform. Cult hero Drew Maggi, who made his first big league plate appearances as a 34-year-old rookie with the Pirates in 2023, did the same.

Marcus Walden is another one of those players who made it all the way back to the Major Leagues to make an appearance—and then made 92 more of them. Between April 10, 2014, when Walden was sent down, and his return to the bigs on April 1, 2018, Walden pitched in the minors with the Oakland Athletics, the Cincinnati Reds, and the Boston Red Sox, along with one year spent in Lancaster with the Atlantic League’s Barnstormers and trips to two separate winter leagues. “After I got released by the Reds after one start, my wife is pregnant, we’re not making any money, and I think ‘Man, I’m done here, maybe it’s time to come home and end my story,’” Walden said of the first season after his brief visit to the show.

“My wife straight up told me there’s no way I was going to split right then and there. I don’t want to be a teacher, I don’t want to go to school, I want to play ball. I’m a ballplayer. I flew out to Lancaster after that and threw something like 32 scoreless innings to end the year, go to Venezuela, and win a championship there. To know someone is behind you too, that’s everything.” When asked what kept him going, the answer was simple. “Somebody already called you up,” he said. “Why can’t it happen again?” Walden wound up sticking in the Red Sox bullpen for parts of three seasons.

On the Society of American Baseball Research’s website, and listed as the backbone of Wikipedia’s phantom ballplayers article, there is a link to a Google Document titled “Near Major Leaguers.” It’s maintained by Bill Hickman, with the help of people who email him to keep the list up to date. In the document are thousands of names—phantom players, players who were on Major League spring training rosters, and non-roster invitees who never made an appearance in a regular-season game. Hickman’s years of work and curation of these thousands of names, some even without any photographic evidence of their life, comes down to one simple idea—the insistence that these guys matter.

As a kid poring over yearbooks and issues of Baseball Digest, it was the names that never made the majors that drew Hickman’s attention. There were many questions about what happened to them and why, but there was also nothing to be seen but their name. “I admired the fact that these players had come so far through the minor league system, and I wanted them to be recognized for their accomplishments,” Hickman said via email. “I was also aware that at the Baseball Hall of Fame and Library in Cooperstown, inquiries would be received about names of players who were purportedly Major Leaguers, and staff would have to simply indicate that they were not.” Without Hickman’s work, this story would have reached the same dead end as so many prior curiosities.

At the end of every conversation, the last question I asked every player was some version of: “Is there something from the inside that you wish people knew about phantom players beyond the story of Moonlight Graham and that vaguely spooky title?” Every answer, surprisingly or not, was remarkably similar to Hickman’s, and to each other’s. Not only do these players have stories and matter, but even getting called up to the majors without seeing or throwing a single pitch makes you one of the most talented baseball players in the history of the sport.

“I know all of us put in a lot of work to reach the point that we did, even if we didn’t play.” Antonini answered. “Being called a phantom player shouldn’t be derogatory, or a discredit to anyone. All these guys are still incredibly good and a lot of it is outside their control and just up to luck and timing. Who’s hurt, who’s not, which team needs a body for a day. What they could control, they did.”

After a short pause, Bugg gave me a near-identical answer. Bugg was a kid who was once guilty of seeing someone struggling in the majors and thinking “This guy stinks,” and now he is an adult who has been around the game long enough to know he was wrong. “So many minor league players are written off as not being good or whatever and from my experience it’s like ‘OK, how do you know that?’ Just because some of us are called up once, DFA’d, didn’t debut, and never make it back, that doesn’t mean we’re not any good. It’s a business, sometimes you need the right people pulling for you, sometimes you need luck and a runway. But if someone gets called up and doesn’t get a shot, it isn’t because they weren’t good at baseball.”

“It’s a respect factor for the guys who got to that point, guys who got that opportunity and were never top prospects, never guys USA Baseball are talking about,” Bollinger said. Just getting there is an accomplishment; taking the next step, he knows, is a matter of luck. “On the right day the team goes extra innings, needs a guy, and there they are.” Or not.

“I would want to say how special that moment is for all of us in that situation,” he continued. “We work our whole life for that opportunity, and that’s our chance. We’re not hoping to get sent back down, but that’s the culmination of everything.”

“I’ve had friends and acquaintances read up on me and say ‘Hey, you made it, but you didn’t make it.’” Jeroloman recalled. “You know, it’s so unique, and it’s almost a situation you don’t wish for anyone to have some days. But at the same time, when you look from the right angle, you achieved the biggest goal you’ll ever set for yourself.”

“You might not be up there for as long as you want,” Jeroloman continued, “but you got to look out from the top of that big hill that every other player you know wants to get to, just for a little bit.”