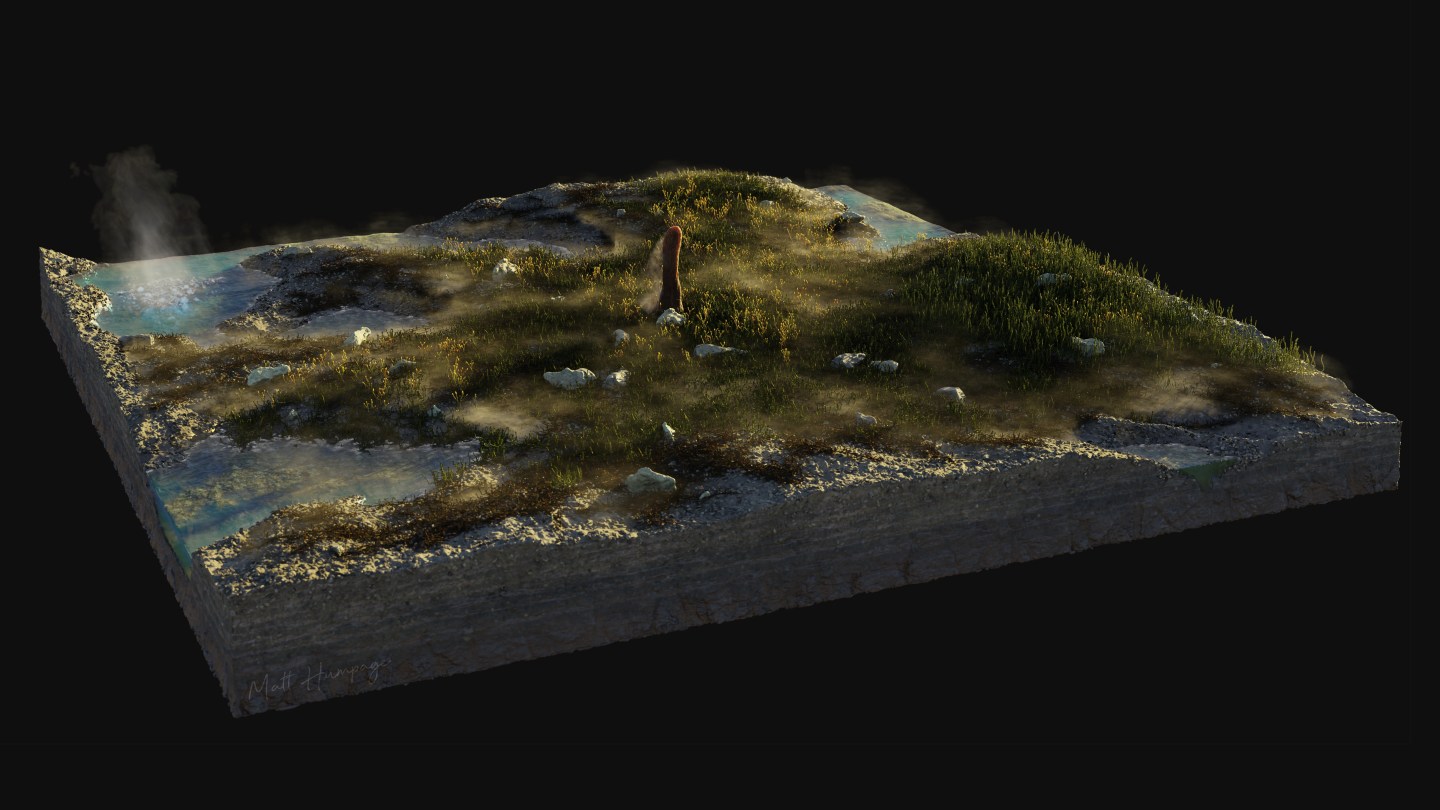

It was a bonnie morning 410 million years ago in what are now the Rhynie chert fossil beds in Scotland. The mists had begun to lift and swirl over the landscape, where hot springs burbled, lichen papered over rocks, and worms slithered as only worms can. Here, almost all life stayed close to the ground. The second-tallest organism at the time, a plant called Cooksonia, grew to a few centimeters at most. This made Prototaxites, an organism with some species that towered above these landscapes at heights of up to 26 feet, an actual behemoth.

Prototaxites was a strange sort of life form. It had no branches, leaves, flowers, fruits, nor a discernable root system. Instead, it resembled a beautiful sausage sprouting from the ground. In this way, Prototaxites was ahead of its time: undeniably phallic in a time long before phalluses existed.

Since the geologist William Edmond Logan discovered the first Prototaxites fossil in 1843 along the shores of Gaspé Bay on Canada's Gulf of St. Lawrence, no one has been sure what, exactly, Prototaxites's deal was. A new paper in Science Advances offers new evidence to the debate, purporting to debunk a prior theory that Prototaxites represented an ancient fungus. But to understand the significance of the new paper, we must first understand the 160-something-year-long argument over what the hell this thing's deal was. This argument, as many do, begins with a beef between a couple of annoying-sounding guys.

After Logan excavated the first Prototaxites fossil, it seems he did not really do anything with it, and as such caught no strays in the subsequent beef. The specimen went unstudied until 1855, when the geologist J.W. Dawson got his hands on the collection and identified the specimen as a fossilized trunk of a conifer. He came to this conclusion because it looked a lot like a tree; specifically, the fossil's "spirally marked cells" resembled those of yews. As such, he dubbed the species Prototaxites, or "first yew."

Dawson's ruling stood until 1872, when the paleobotanist William C. Carruthers tore Dawson a new one in a 17-page rebuttal that argued Prototaxites actually represented a shard of a large species of kelp, such as Lessonia. Carruthers boldly (and illegitimately) renamed the specimen Nematophycus, or "stringy alga." Carruthers also took the opportunity to take some scathing digs at Dawson, including but not limited to: "an intelligent or educated observer would at a glance see the true nature of these smaller structures," and "it is difficult to conceive how such a series of errors first took possession of Dr. Dawson’s mind," and "if Dr. Dawson knew anything whatever about a vegetable cell, he would not have written such nonsense as the first sentence in this footnote." At the end of the paper, Carruthers quotes various friends and colleagues "whose algological labours are well known" to conclude "it is superfluous to say that I have never met with one who for a moment imagined the fossil could be coniferous." One can only pity Dawson, a man of presumably very few, if any, known algological labours.

Carruthers's classification stood until the botanist Arthur Harry Church suggested in 1919 that Prototaxites could be a fungus. But his suggestion was ignored, presumably because he did not think to include any scathing digs in his paper. Dawson, undeterred by Carruthers' spite, traveled to the fossil's discovery site and found many more Prototaxites "trunks," which convinced him even further that the fossil was once a conifer. Dawson was writing a book about plants at the time, and he drew an illustration of what a Prototaxites tree might have looked like, an illustration that looked a lot like a conifer. But as more scientists studied the structures of Prototaxites, it became clear the fossil was not a conifer after all. So Dawson quietly (and illegitimately) renamed the species Nematophyton, or "stringy plant," and vehemently denied he had ever considered it a conifer, despite his abundant paper trail calling it a conifer. Upon reflection, maybe Carruthers was right about this guy.

I learned about this beef because the paleobotanist Francis Hueber chronicled the debate in a 2001 paper in the Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, which doubled as Hueber's foray into Prototaxites identification. (To Carruthers's credit, Hueber was also annoyed by Dawson, noting the geologist took field notes in an "illegible scrawl," failed to mark down where he collected specimens, and misplaced many fossils; as such, it took Hueber 20 years to retrace Dawson's research and publish his own paper.)

Hueber argued that the fossil was actually a giant fungus. He noted that the insides of Prototaxites, which comprise three kinds of extremely tiny interwoven tubes, resemble no plant. Rather, Hueber interpreted these as fungal hyphae, the threadlike filaments of fungi. Hueber's argument was missing one key element: fungal spores, the reproductive elements of fungi, which would have been a smoking gun. But after 20 years, he felt he'd done enough to prove his case, and made a bit of an emotional appeal:

"There was a time when the size of the dinosaurs was not readily conceived nor believed, but as knowledge of their structures, habits and habitats increased they soon became 'real'. They are now accepted, so much so, that young children identify them by genus well before they are doing multiplication tables. So is it not possible to accept Prototaxites as a gigantic fungus on the evidence at hand?"

In 2007, Hueber and colleagues marshalled more evidence. They published a chemical analysis in Geology that compared the type of carbon in Prototaxites with other plants living at the same time. Plants only take in carbon dioxide from the air, so plants living during the same period of time would have the same ratios of certain carbon isotopes. But the carbon ratios in Prototaxites did not match what was expected of a plant of that time, strengthening the evidence that it was a fungus that absorbed carbon from other sources. When Hueber died in 2019, his fungus theory remained the prevailing theory of Prototaxites.

Unfortunately for Hueber and Church (and Dawson, and Carruthers, I suppose) this new Science Advances paper argues that Prototaxites is not a fungus after all. The researchers examined the interwoven tubes of the Scottish species Prototaxites taiti and found its chaotically interwoven tubules did not not resemble the orderly patterns of fungal hyphae. And a chemical analysis revealed Prototaxites had no chitin and glucan, which are crucial building blocks of fungal cell walls and were present in other fungi in the area at the time. "Prototaxites therefore represents an independent experiment that life made in building large, complex organisms, which we can only know about through exceptionally preserved fossils,” Laura Cooper, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh and an author on the paper, said in a statement.

So everyone was wrong! Prototaxites was literally built different. The mysterious 26-foot-tall pillars may not have been fungi, plants, animals, or protists, but rather hailed from a totally separate kingdom of life. Or at least that's what the new paper argues. To its credit, the authors did not go Carruthers mode, and were very respectful to all the researchers who came before in the Prototaxites saga. Of course, this new paper doesn't really resolve anything; it's likely that more research will continue to shift and clarify Prototaxites's position on the tree of life. Perhaps there are even more beefs to come, if only researchers will be daring enough to bring back scathing barbs to the annals of scientific publishing. It's the least they can do for Prototaxites, an organism that would have been an icon in any age. If only the annoying guys of this age would devote themselves to the mystery of Prototaxites, maybe society would finally have a chance to heal. But what the hell do I know! I'm not a man of algological labours ... yet.