As you may have heard, the twinned industries that produce art and criticism in this country are embattled. On every side, there is steady conglomeration, privatization, and the rapid uptake of labor-annihilating technology. In tandem, there has been a steady mainstreaming of an anti-intellectual attitude that finds criticism, particularly negative reviews, to be pretentious and without lasting cultural merit.

Reading A.S. Hamrah, the film critic at the magazine n+1 and a prolific writer on the history and trajectory of cinema at large, will convince you that criticism remains vital. For over two decades, Hamrah has honed an uncompromising, incisive voice, taking advantage of his rigorous and wide-ranging knowledge of the cinematic project so that no one film stands untethered from another. In recent years, amidst a media landscape that is overstuffed and underbaked, Hamrah has continued to chronicle the downward spiral of our time with unflinching clarity.

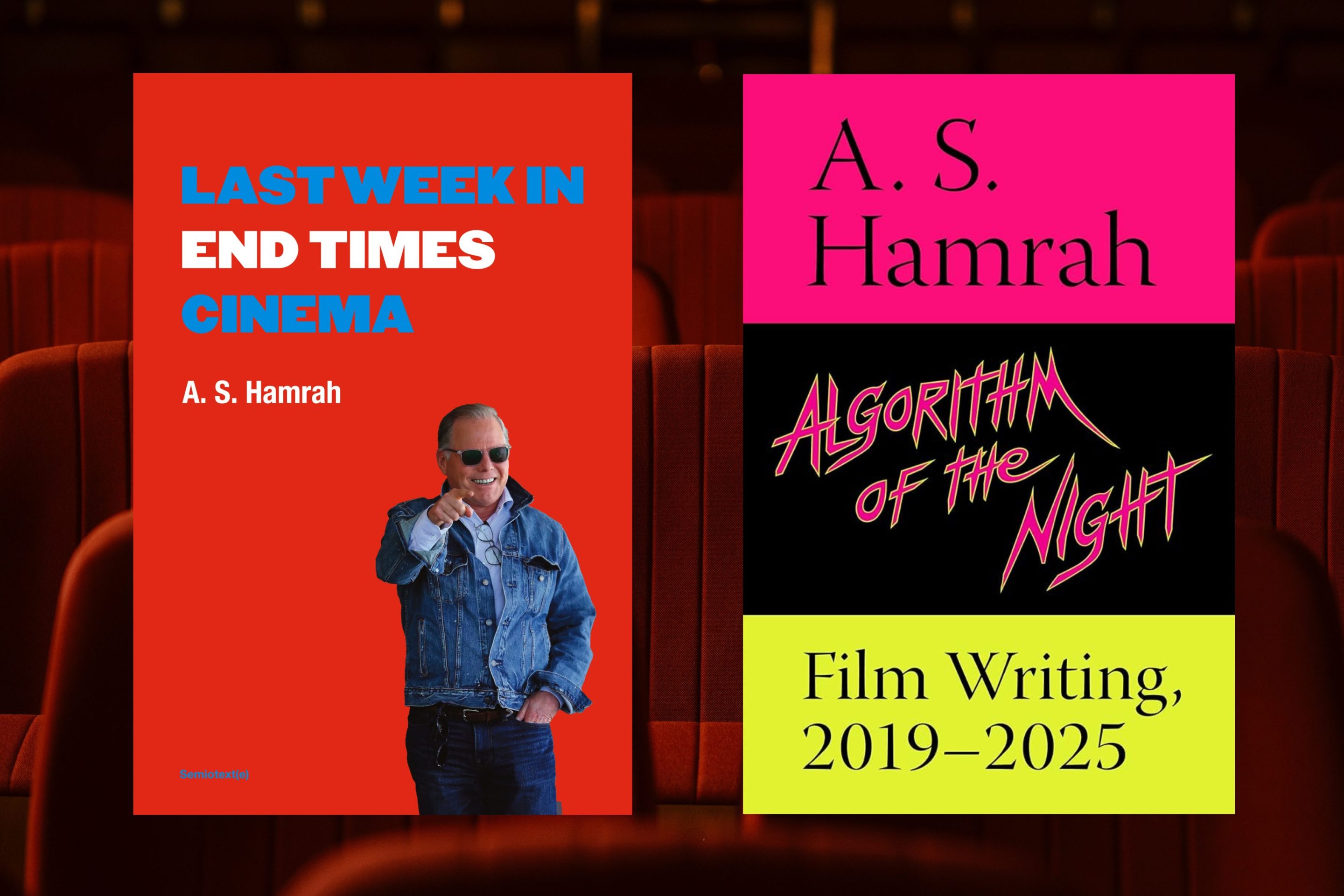

Two new books, Last Week in End Times Cinema and The Algorithm of the Night, collect select pieces of Hamrah’s film writing across various outlets from the past six years. As the reader moves through traditional reviews and longer ruminations on specific filmmakers and films, a novel historical document emerges, one that witnesses the degradation of an artform while also championing the independent and underground entities, whether individual people or larger movements, pushing back against a tide of slop and cookie-cutter cinema.

I spoke to Hamrah over the phone about the state of the film industry today, the demarcation between cinema and Hollywood, the generational uptake of technological innovation, and what it takes to make a living as a critic today. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

These three books—The Earth Dies Streaming, Last Week in End Times Cinema, and The Algorithm of the Night—are productive historical documents. You follow cinematic history as it's developing. This is a broad question, but I’m curious about your feelings regarding the trajectory of cinema in the modern era.

That is a big question. By the modern era, I assume you mean the 21st century.

The 21st century.

I think there's been an increasing consolidation of studio power in America to make increasingly more infantile films. In the history of cinema, there's never been a time in which the studio heads had more power than they do today. That's been facilitated by digital cinema. Directors have less power because so much stuff is shot now so that it can be edited in various ways and used in various ways. The mergers and consolidations that are going on now are very bad for the future of cinema and Hollywood. There's a difference between the cinema and the Hollywood film industry that I think is important to consider and remember.

But starting in the 21st century, after this great flowering of independent cinema and adult cinema and violent cinema in the ’90s, we saw a return to childish cinema defined by the Lord of the Rings movies, the Harry Potter movies, in the rise of the Marvel movies, which were also very white in my opinion. I would include television reboots, things like The Dukes of Hazzard. And then the streaming aspect of it is about the destruction of theatrical exhibition, which I think is one of the goals of the studios.

When reading your essay looking at Spike Lee’s Bamboozled and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, I was thinking about the arc of Spike Lee’s career. From these incisive independent films to shilling for crypto and working with tech-companies-turned-studios. He seems like an interesting microcosm of certain forces in the industry.

I mean, Spike Lee is a survivor and he will do what he has to do to keep making films. There's a great difference between the Spike Lee of 2025 and the Spike Lee of She's Gotta Have It. When I think of Spike Lee, I think of the trailer for She’s Gotta Have It, which is the first thing I ever saw by him. He's come a long way from playing Mars Blackmon selling tube socks. He's living the high life now. And his newest, Highest 2 Lowest, is a remake of High and Low. So maybe that speaks to that in some way. I'm not really interested in that to be quite honest. I know it's an A24 film, but I think Apple Original Films are just so dull and big and stupid, you know, they're not of interest at all for the most part. I have no problem with A24 and I don't understand A24 derangement syndrome.

What do you mean by that?

So the big five studios or however many there are now kind of all make the same films. There's no difference like there used to be between Warner Brothers, Paramount, Sony and Fox or Disney or whatever. In the classic period of Hollywood, there was a big difference between Paramount and Warner Brothers and MGM and Universal and Columbia and RKO. You could tell just by looking at it which studio it was. They had a house style. A24 is just an example of that today. I don't see why this bothers people. It doesn't make any sense to me. I think they make a lot of films every year. They make a lot of really good films every year. They support their favorite auteurs. They produce a lot of films by women. I don't understand the animosity towards A24.

Now, they keep talking about AI. There was that very fawning piece about A24 in the New Yorker, which ends with the revelation of their AI division. That makes me nervous about A24. I think it's foolish for them to do that. But I really don't understand people's animosity towards A24.

I think part of it has to do with their branding, this sense that they’re monetizing their films over and against the actual films themselves.

Every company does branding. The studio that's tainted is Mubi. Talking about branding and merch, that’s the main thing that Mubi does. I completely reject this feeling that people have towards A24. It's a form of resentment that I do not want to participate in.

I think this puts viewers of cinema and critics in an interesting position, though. Fewer choices in terms of studios creating compelling work that’s either affordable or just marketed with enough power to get a lot of people to even know it exists, coupled with a wider access to cinematic history and knowledge. That’s not to say this necessarily makes people smarter, but it does feel like there’s a greater sense of discernment. Letterboxd, for better or worse, fits into that conversation, I think.

Well, as Francois Truffaut said, "Everyone in the world has two jobs, their own and film critic."

I think the average cinephile does have access to a wider range of behind-the-scenes knowledge now. That includes knowledge not just of the American film industry, but the European film industry, of festivals, of all sorts of things going on in the world of cinema. There's more dissemination of that kind of knowledge because of social media. I don't really care about Letterboxd. It's a social media site. I'm sure it'll get worse over time. But, I also think Letterboxd is mostly for young people. It's good to hone your skills as a writer if you take it seriously. I have no objection to that. It's probably a good thing in some ways, but I don't trust it because it's a social media site and it's subject to the same kind of enshittification as all the other ones.

You write full-time now, right?

I do. I’m the film critic at n+1. I’m a member of the National Society of Film Critics. And I’m a freelance writer. I quit my job in 2016, when I was a semiotic brand analyst for the television industry for eight years.

Did that job lend you any sort of insight into the industry or the time?

Well, that was a thin slice of the 21st century. Before that, I did the same thing for consumer goods and other kinds of brands. But that was just my day job. I didn't like it, I was only doing it for the money. It totally changed my relationship to television—ruined it, really. It did give me a lot of insight into the business world around cultural production or television cultural production. Television kind of sickens me now, in general. It's not a director's medium, which is kind of what streaming is turning movies into, something that's not a director's medium. But every bad thing that anyone's ever written about television, from Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television to Amusing Ourselves to Death—my experience in that industry proved all those things to be true to me.

I was also shocked by the stupidity of the CEOs in television. I didn't expect them to be geniuses, but they were, for the most part, not interested in their product and didn't watch their product. They were just businessmen who would often come from other areas. One guy could have been the CEO of a soda company or a basketball team. The entire CEO class just move from position to position with no regard for the product they're making. Which is also true with the film studios now.

It sounds like Zaslav.

Who's a corporate lawyer who was in cable television. Doesn't really know anything about movies, has bad taste, is a coward in the kind of productions he oversees.

Loves The Flash.

Loves The Flash. The main thing about these people is their cowardice. They're not risk takers. They're interested in technology when it comes to innovation, but not in innovation in the form of the art forms that they're in charge of. They're not even Philistines. They're not even vulgarians in the sense that some of the studio executives were in the classic era. They're not smart enough to be vulgarians.

A lot of times, when talking about the current era of Hollywood versus those of the past, there’s a kind of nostalgia for studios that had a point of view. The ’90s and Miramax come up a lot here. Maybe that’s just because they were louder than everyone else. But invariably, a place like Miramax is inseparable from a person like Harvey Weinstein.

Well, the real great studio of the ’90s perhaps was not Miramax but Fine Line and New Line. They were more innovative than Miramax. Miramax just got more press because Harvey was so interested in Oscars. But the fact is that both Miramax and New Line forced the majors to create indie divisions, or to absorb them. Both those companies were absorbed by the majors, one by Warner's, the other by Disney. The absorption of those things is one of the defining factors of the 21st century. As a New Line product, The Lord of the Rings is kind of interesting. As a Warner Brothers product, less so. I think, right? It's hard to say why that is, but there is a difference.

Someone who really cares about his product still is Tom Cruise.

He's got the right idea about how to make movies. I don't necessarily like all the films he makes. But he understands movies and he cares about them, and he's kind of forced other people to think that way, to some extent. I'm not a huge Christopher Nolan fan, but he's done the same thing. And of course other people like Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson do that too.

I was noting the greater rise of theater chains rescreening films lately, and it reminded me of a line in one of your books where you say that audiences will go to the theater when they have actual options. I’m curious about how you feel the audience’s attitude toward the cinema as a physical place has changed.

I think the attitude of older Americans, baby boomers and older, has changed considerably. I think that started during COVID. I think now they're very smug about the fact that they never go to the movies. They brag about it. And if people tell them that other people are going to the movies, they simply say it's not true. That happened to me once. I was talking to some older people and they were telling me that no one ever goes to the movies and I said, “Well, I had just been to the movies that day,” and they basically said, “No, you haven't. No you didn't.” I think it has to do with their insane embrace of technology, their death-drive embrace of technology.

There’s always been some hypocrisy when people accuse younger generations of their addiction to technology. It’s not specific to one generation—

Hold on a second. I think it is. I think it is specific to only one generation and I want to be very clear on that. Sure, there's a lot of people who are addicted to their phones. Of all generations, and more young people probably. But old people also.

Well, I was going to say that people like Zaslav are a good example of the fact that, with the exception of people like Sam Altman and Zuckerberg, it’s a lot of old white guys at the helm: Larry Ellison, James Dolan, Trump.

The gerontocracy. The people who think they're immortal or somehow they're going to live forever. (Say what you want about Trump, he does seem very cognizant of the fact that he's not going to live forever now.) They're all old billionaires and they want to completely dispense with all the labor that produces culture.

Last summer, I did some reporting here in Vegas about the Wizard of Oz Sphere spectacle. It was difficult not to feel a sense of disgust with not only the people behind it, but the audience who were so eagerly engaging with it.

It's because that’s a theme park audience. A theme park audience is essentially a low-brow audience. An infantilized audience and a childish audience. We’re not talking about the cinema. We're talking about a form of post-cinema or abused cinema, really what Siegfried Kracauer called the mass ornament. This bauble that appeals to an undifferentiated mass of people. That's the audience that the Hollywood studios believe in.

It’s an expensive proposition. Ticket prices were insanely high.

One of the main problems with mass entertainment now is the cost. Streaming is the best example of this. All they care about is price gouging. It's far too expensive to go to a movie now. A small popcorn costs $10.50. The whole thing is a shakedown. But the audience that you saw at the Sphere is the audience the studios believe in now. That's why movies are so infantile, and why they're all intellectual property movies now and franchises and prequels, sequels, legacy sequels, reboots, versions of TV shows. It's this kind of foreverism. These things never go away. You're never replaced by anything new. This is part of the cowardice I'm talking about of the studio executives.

One of the most moving sections in The Algorithm of the Night collects your writings about and during COVID. You note at various points how many days it had been since you sat in a movie theater and I remember a similar sense of dislocation. It was a little disappointing to have to watch new and interesting movies at home.

I never had any streaming services before COVID. I watched every movie in theaters. I spent my entire life in movie theaters. I was a movie theater projectionist for seven years. So I had to re-orient myself to see new films at home. One thing that was strange at that time was that critics just acted as if they were still watching them in movie theaters. I don't think seeing a film at home is the same thing as seeing the film.

The defining aspect of cinema is not just large-scale projection, not just seeing it in the dark with strangers. The defining aspect of the cinema is that you don't control the time at which it starts and stops. There's no pausing it. There's no watching it over several days. That is very important to the cinema, I think. When you are the one controlling, in effect, the projection of the film, it's something completely different. I think that's a way to review the film. As opposed to reviewing the film. You see what I mean? It's a second viewing mode more than a first viewing mode.

I remember very clearly I was watching a German documentary called Heimat Is a Space in Time. That's a five-hour German movie about trains and about the Holocaust, and about a number of other things in German history. It's not the most exciting movie. But I watched it over five days. And it was completely different than seeing it in a movie theater. And the impact it would have had seeing it in a movie theater would be much stronger and very different than seeing it at home. The home viewing experience is going to make it harder to make films like that. They will become episodic. And people's laziness is so cosmic that no one's going to really care.

Your books are part of an increasingly small genre: the film essay collection. I imagine it’s a different project to put these pieces together when they originally stood on their own.

I definitely think the book becomes something all its own. Those pieces in the new book or in the previous book only represent a percentage of my output in that period. So it's very considered, and my editor and I work carefully to pick those and to put them in the order that they ran and so on. They're mostly in chronological order but which ones get to be there is important. I do think the book becomes a chronicle of a sort.

How do you typically choose what you watch and write about? Is it a matter of seeing what interests you, in addition to things that may not interest you but perhaps some greater value as a comment on something else?

Yeah, that's exactly right. I don't have a full-time job as a film critic. n+1 is not a full-time job. I am able to watch more of what I want to watch. I don't have to watch everything like if you were the film critic for New York magazine or something. I wish I were in that position.

To have to watch more?

No, just to have a full-time job as a film critic.

Why do you think that’s such a vanishing proposition now?

Because, as you know, journalism is a shrinking industry. It's a profession in which very few people have full-time positions and magazines or newspapers. The death of the alt-weekly really triggered this. It has had a very bad effect on people's understanding of the cinema. People don't even know what movies are out anymore. Despite all the social media marketing that's done now, nobody knows what's playing or where it's playing. Right. You know, André Bazin famously asked, “What is cinema?” The question now is where is cinema? You meet people all the time now, you tell them about some well-known film, they haven’t even heard of it. It used to be because of the local paper with all the movie movie ads in it and the movie clock. And the alt-weekly would have every movie reviewed and all the listings for the show times.

There's nothing anyone can pick up anymore that shows them all of that. And to say that you can do that on your phone is ridiculous, because the information is presented poorly. There's no larger view of what's playing all at once now. I'm consistently shocked by how little the average person knows about what's playing at movie theaters. I saw Marty Supreme the other day on Christmas at a cineplex in New Jersey. I don't even know what some of these other movies are. I don't know what David is.

I don't know what David is either.

Yeah, well, look it up. You'll be shocked to find out. The audience is too atomized now.

Your Oscars coverage is how I first saw you. Those pieces always go a little viral.

That's definitely the most popular thing I write in the year. Tens of thousands of people read that in like the first two days that it's out.

Do the Oscars matter?

The Oscars never mattered. The Oscars only matter economically to people that win them, and now that doesn't even matter because Sean Baker hasn't made another film since Anora. Mikey Madison hasn't been in another movie since Anora. But I never thought about that stuff when writing about those films. My goal writing those columns is to write about every film that's nominated for a major Oscar, plus some others if I feel like it, and to not succumb to the hype of award season Oscarology, which is absurd. I want to approach all that from a completely different angle. I'm not trying to participate in the way that most people are forced to if they're critics. I don't think anyone really wants to write like that, but they have to in their jobs. I just look at each film individually. I don't prioritize any films over any others that are nominated for Oscars. To me, it's just a group of films that I'm going to write about in some way.

I appreciate that your reviews are either as long as or as short as they need to be.

That's one of my guiding principles. There's so many films that get reviewed where there's no reason this review needs to be this long. At a certain point you're just treading water. I don't like the way that film criticism is structured, which is mostly, We're going to do two films a week in our publication. One is the big important film, which is going to get more space. And the other is the less important but perhaps more interesting film that's going to get less space. It's embarrassing to me that someone like Anthony Lane, who I never liked, had to write this long piece on like the latest Avengers film, then there'd be a four-paragraph piece on an actually good movie.

Anthony Lane was the reason I used to skip the movies section of the New Yorker.

He wasn't funny. If he had actually been witty, it would be different. But you can't be witty about something that you don't care about at all. You always got the impression that he only saw the movies he had to see to write about them. That's not being a film critic.

I’ve only ever known freelancing as a critic, and I have friends who dropped out from pursuing it because they couldn’t make enough money cobbling together assignments from a bunch of different outlets that don’t pay all that well. The staff writing gig is one of those pipe dreams that people speak wistfully about. I’m curious about what you’ve been able to accomplish through such a long career in film criticism.

That's a complicated question. There’s a couple things. My first book did quite well. It sold out its first print run in a month. It was positively reviewed everywhere, it got great word of mouth. Especially by the standards of the small press, it was a big success. And I think it proved that people are interested in collections of film criticism by critics they like to read. However, when the Boston Globe was looking for a new film critic, I think it was in 2022, I applied for that job and they didn't even respond to me. So I just have written off that entire sector of film criticism, from the New York Times on down. And if you look at papers, even the Times, the critics don't live in the cities where they're writing. These are just nebulous people somewhere in the world. That's not good. All film criticism is local, just like all politics is local. That's the first thing.

Secondly, I approach this as my job. So that means that I don't have another job. I did that already and I didn't like it. I made a lot more money at my old job and so on, but I wasn't living the high life. So I've given up on that too. All I do is write. That's it. And whatever kind of life that entails, or whatever I'm denied by doing things this way, it's fine with me. This is a choice that I've made. I take it seriously and this is what I do. I'm not going to have a 9-to-5 job anymore and also do this. I did that for many years of my life, and I feel that those were wasted years. (I mean, being a projectionist was not wasted.) So that's all there is to it. There's no going back, in other words.