For over a hundred years kids have been writing letters to Santa, sending off their Christmas wishes to (children: stop reading) completely made-up addresses in Alaska and the North Pole. Until recent history, the vast majority of these letters ended up in the (children: I'm begging you) Dead Letter Zone, where they would lay unopened until being dissolved into pulp and recycled. Around the turn of the century, the public outrage over this admittedly troublesome practice started to become a problem, and the U.S. Postal Service was moved to allow local charity groups to read and respond to the letters.

Starting in 1912, postal workers and citizens alike could view children’s letters at their local post office and choose which ones they’d like to adopt, fulfilling the kids' wishes and delivering them the presents they requested from Santa. The post office formalized the project, called Operation Santa, in 2006. Each year, a network of volunteers and postal workers attempt to find benefactors to fulfill the wishes of thousands of kids.

Although the Postal Service began digitizing some letters in 2017, this year's operation has gone entirely digital due to COVID-19. Instead of being physically displayed at a handful of post offices, every letter has been anonymized, scanned, and uploaded to the Operation Santa website, for anyone to read and adopt with a click of a button (once the letter is adopted, it's removed from the site). This year also marks the nationwide expansion of the project, meaning for the first time we have a substantial digital record of a monumental letter-writing tradition that dates back to well over a century in this country. The scant record of letters to Santa we have throughout history are fascinating sociological documents, and this year, of all years, we had tens of thousands of them accessible to anybody with an internet connection.

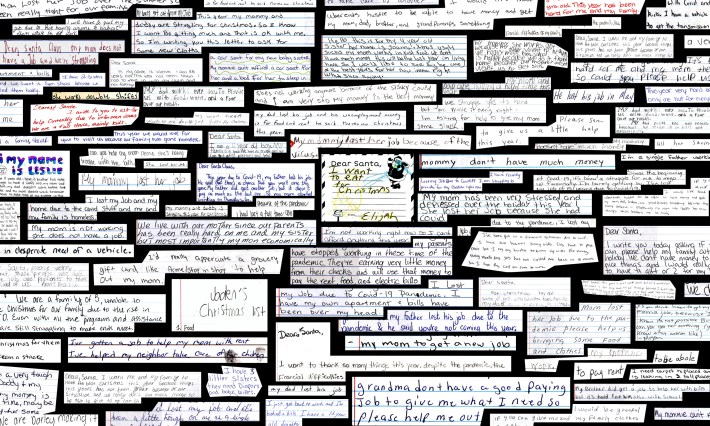

I wanted to know what kids were asking Santa for during a pandemic, so each day from Dec. 4, when the first batch of letters hit the website, to Dec. 13, I spent hours engaged in the surreal, intimate, heart-wrenching practice of reading children’s letters to Santa Claus one after another—about a thousand in all. This year, Operation Santa is an explicit look at the disastrous impact of COVID-19 on America’s poor and the utter failure of the government's response.

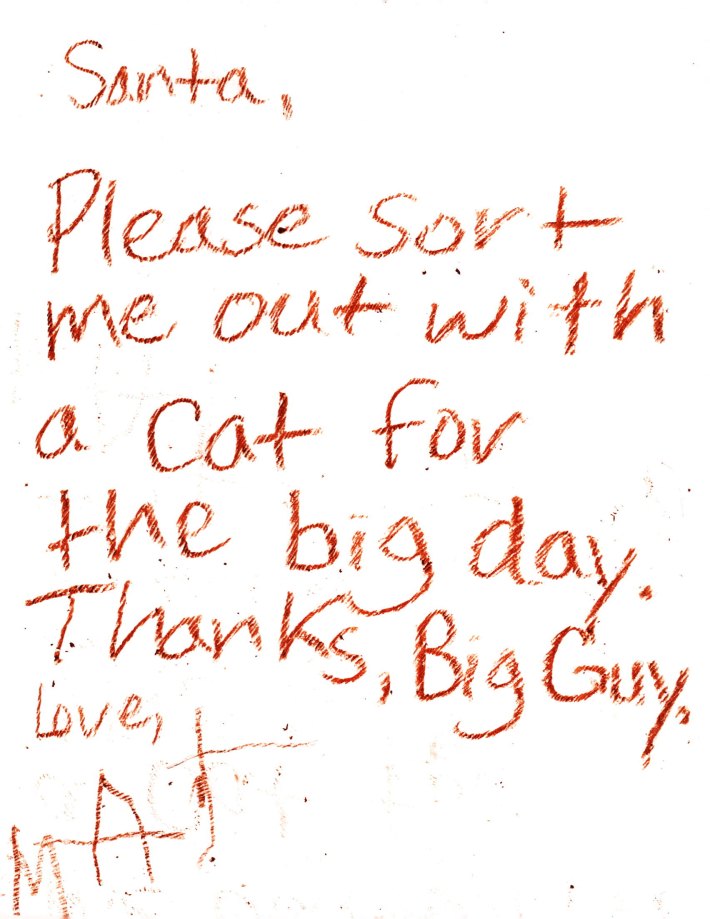

As documents the letters are endlessly captivating, dense in their joys and sorrows. Some of them were laugh-out-loud funny. Young Braxton asked for "money 1000 [smiley face]," while Jaden wrote, "THIS IS JADEN CHRISTMAS LIST" underneath a list containing the UK, French, and German versions of the TV show Fraggle Rock. One child named Tory asked for a "Union Pacific 4449," a literal train that hasn’t been in service for 70 years, and Mat’s entire letter was, "Dear Santa, please sort me out with a cat for the big day. Thanks big guy."

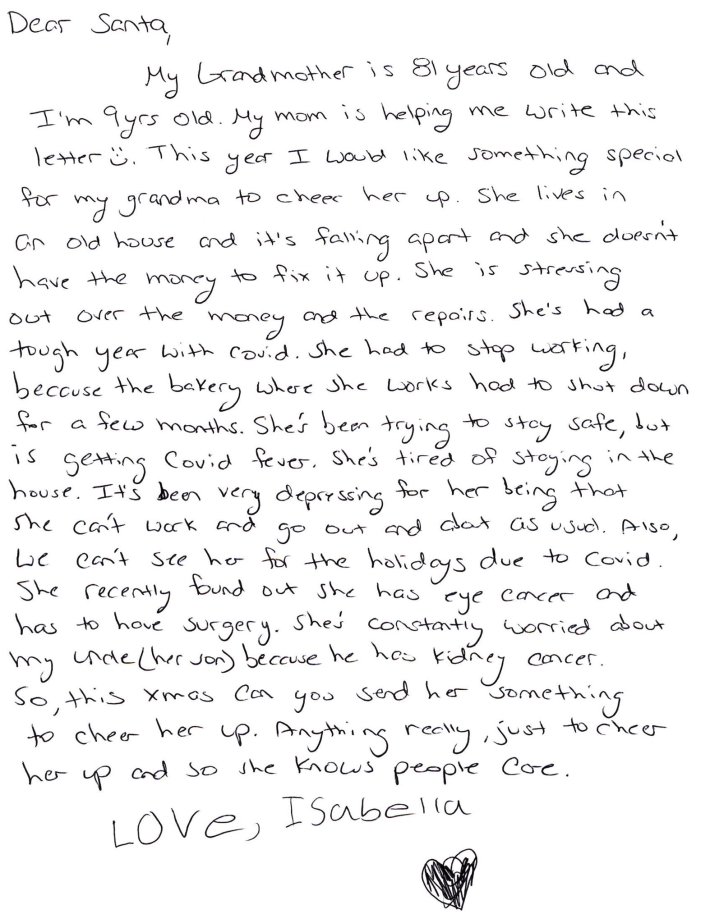

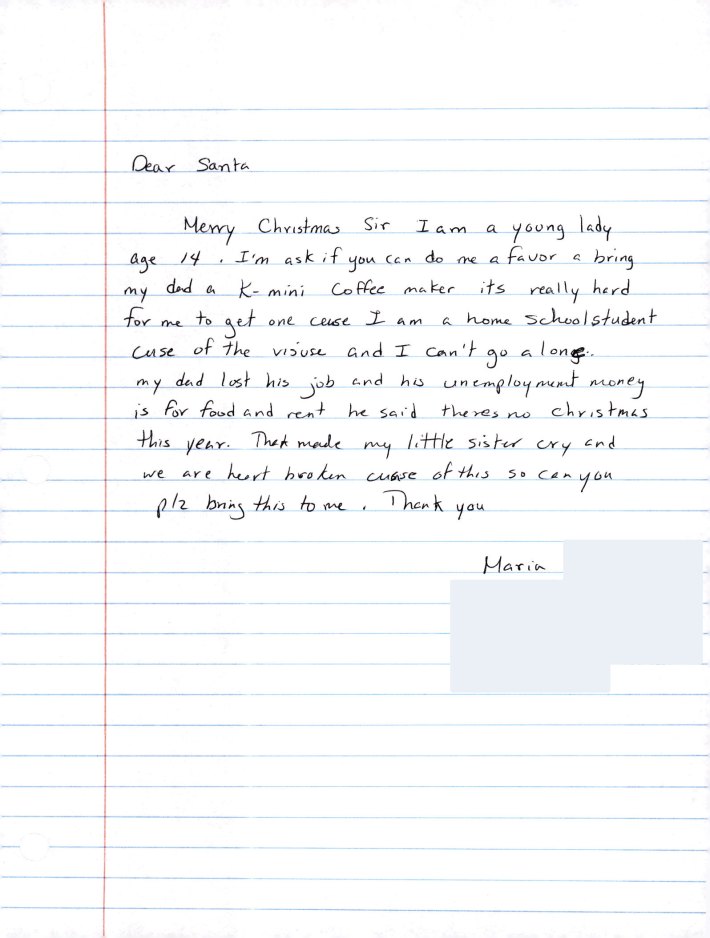

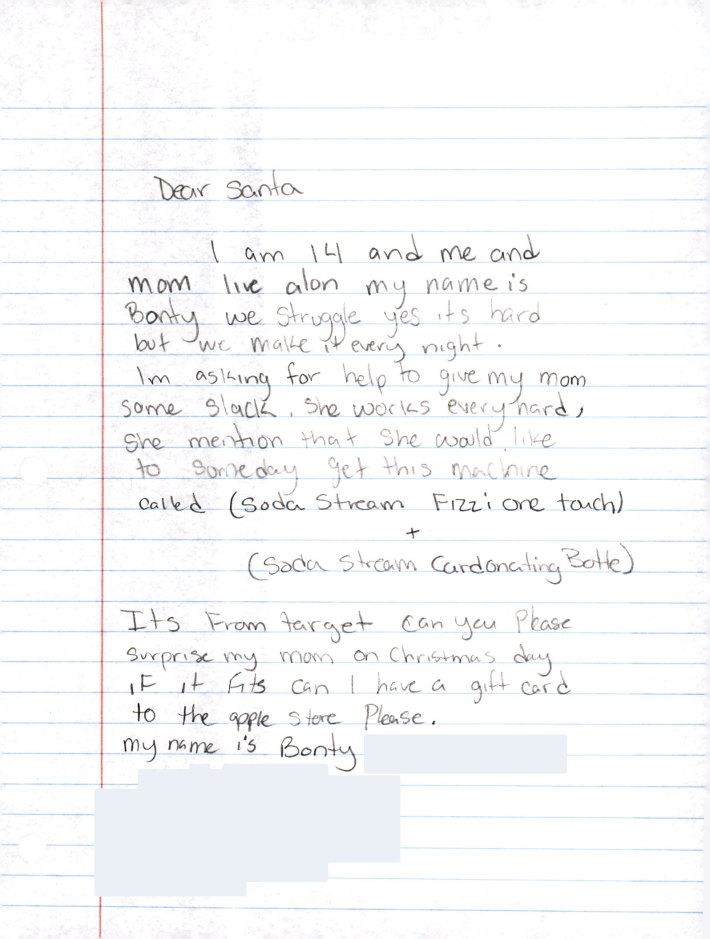

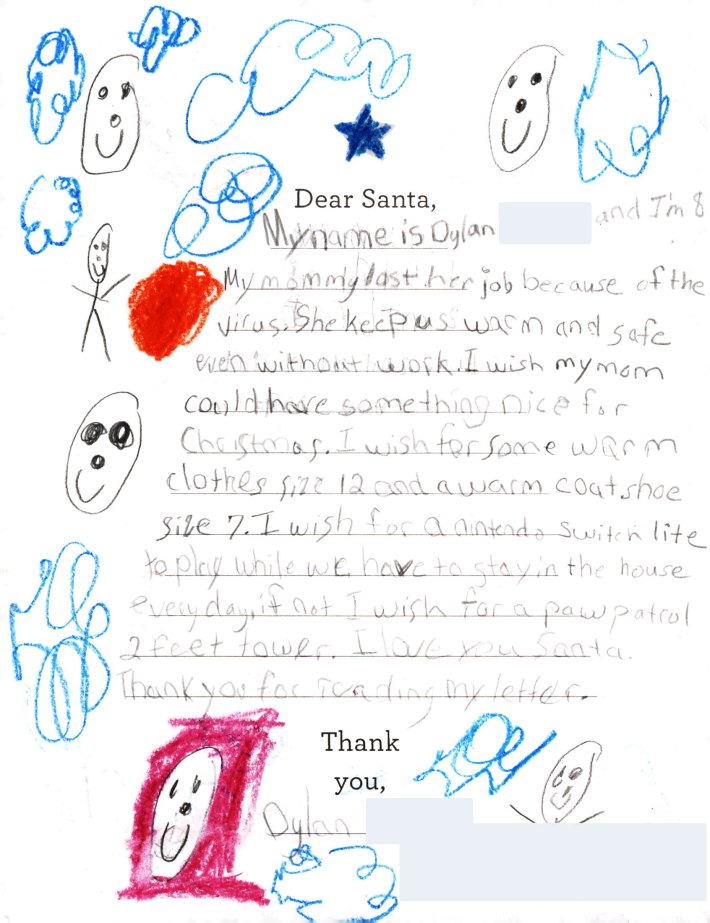

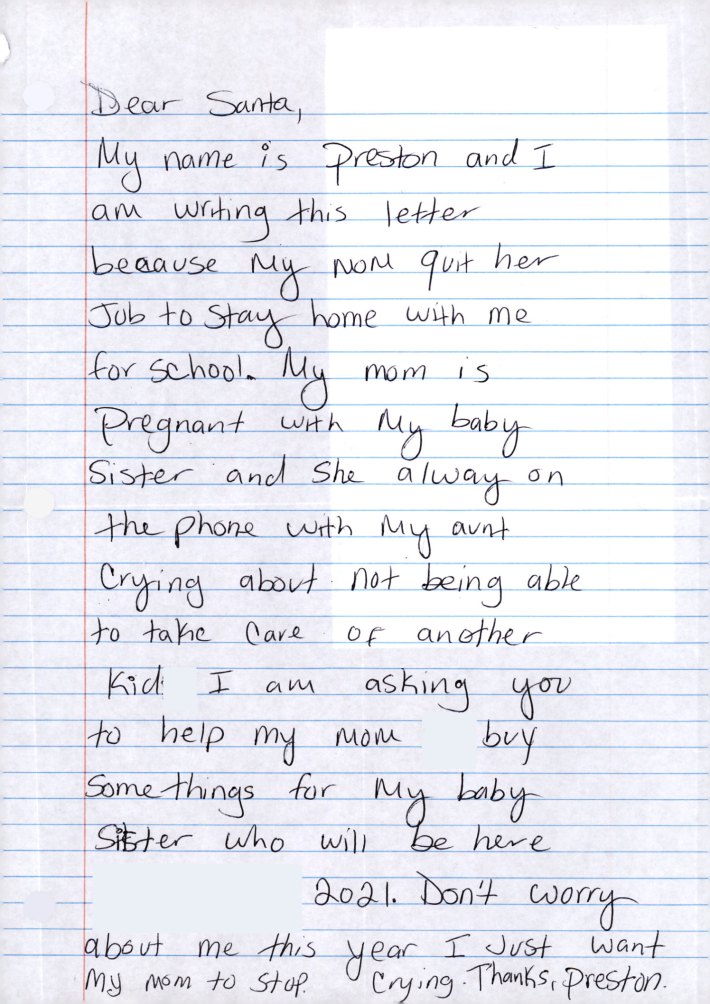

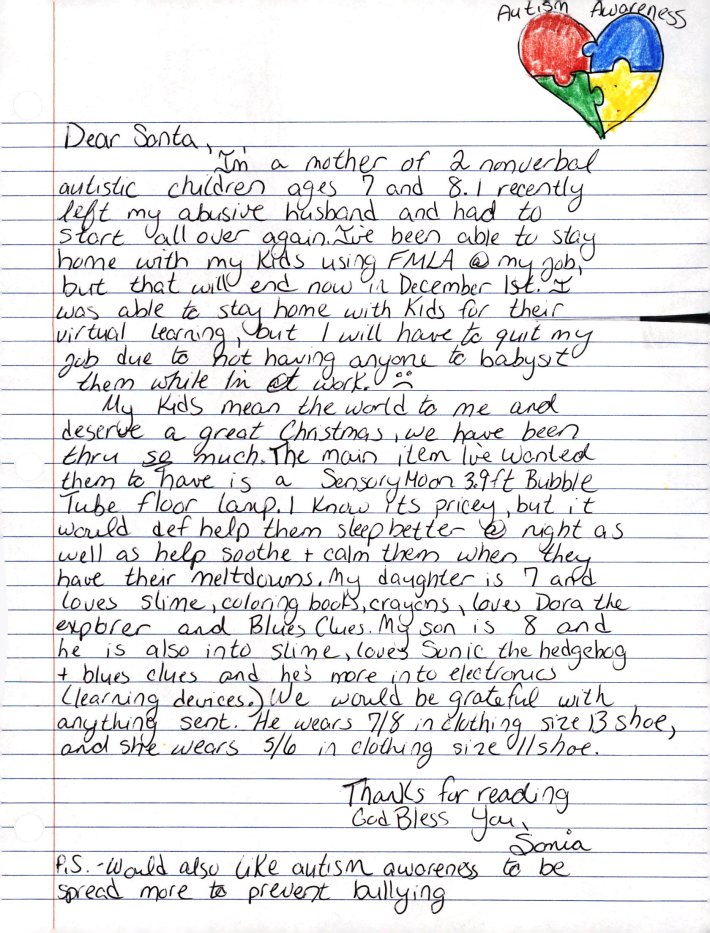

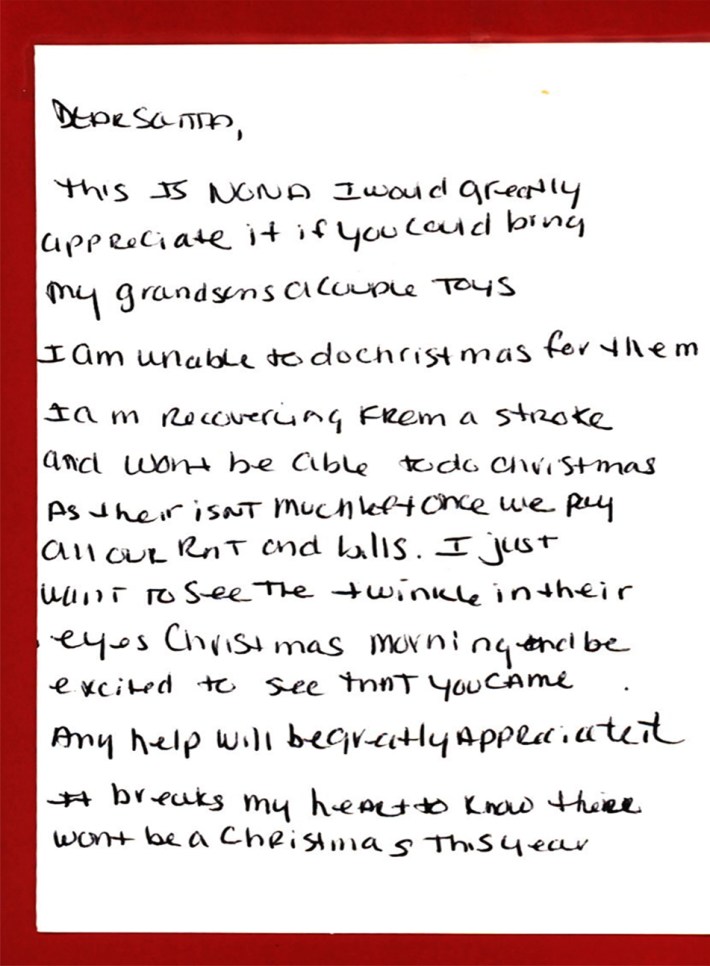

But just as many others were filled with despair, dire financial circumstances, and desperation. COVID-19, job loss, and economic hardship had a staggering presence, far more than I even expected. It’s a particular kind of emotional torture to read the letters one after another. I’d actually bawl at an unbelievably sweet letter of a child asking for "a bird a small one," and seconds later bawl even more over a gutting letter of a parent asking for diapers and size 2 shoes.

Some of the letters were so precious they shorted out my brain entirely, producing only the simple and absolute conviction that I would slaughter my way through the Nine Circles of Hell to secure the child a Nintendo Switch. The whole experience was filled with these kinds of gut-punch juxtapositions. Brightly colored scribbles asking for "a fuzzy bathrobe like mama’s" or "a puppy, not an electronic puppy, a real puppy with a real heart" were a microsecond scroll away from the unmistakably grown-up handwriting asking for grocery store gift cards, motor-skill toys for their newborn baby with Down syndrome, help with the bills, or a mattress to sleep on.

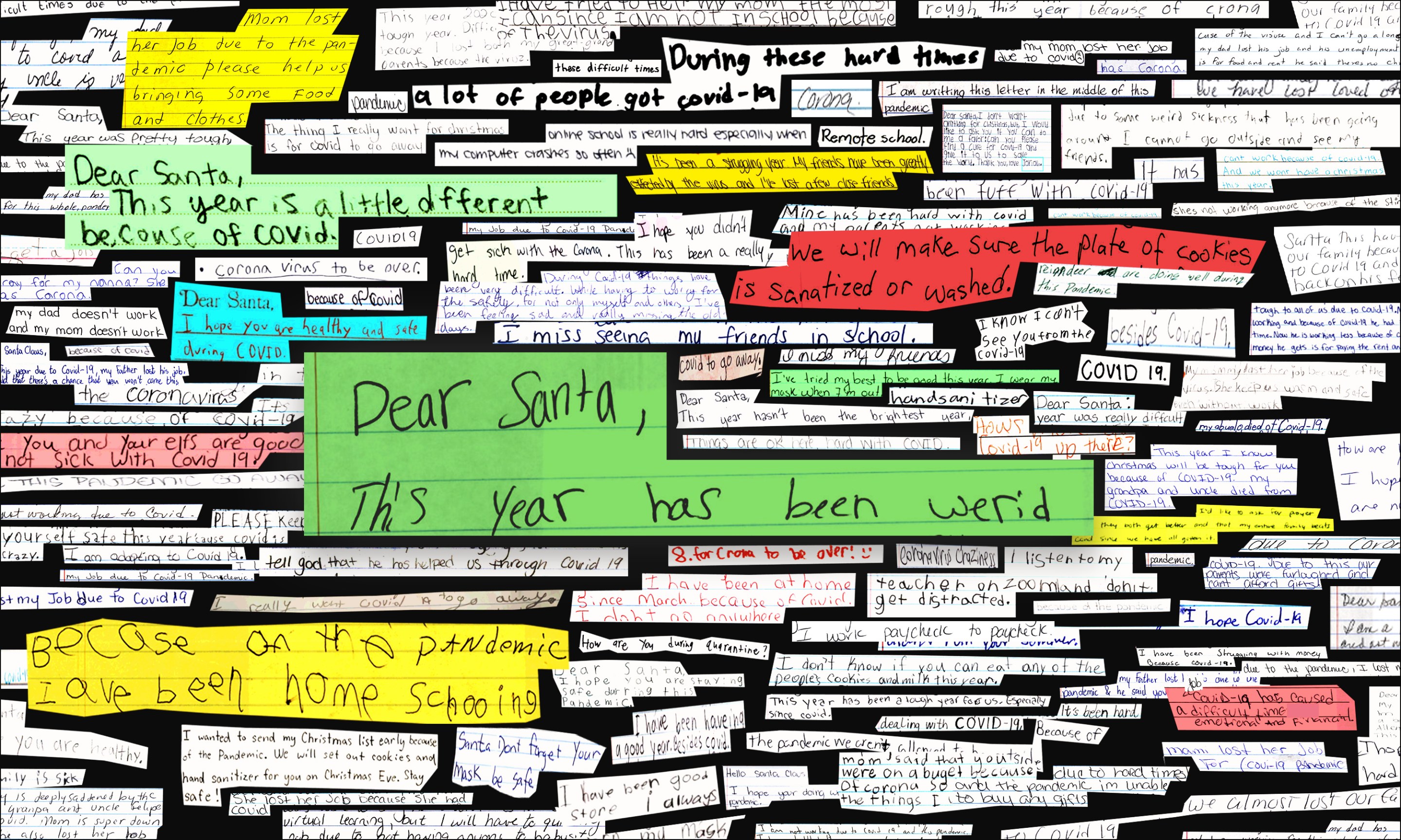

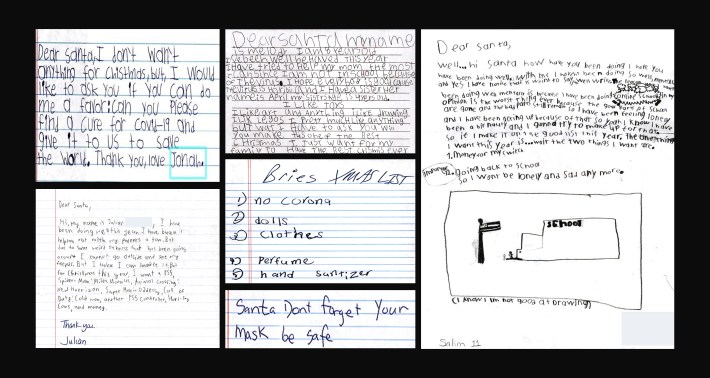

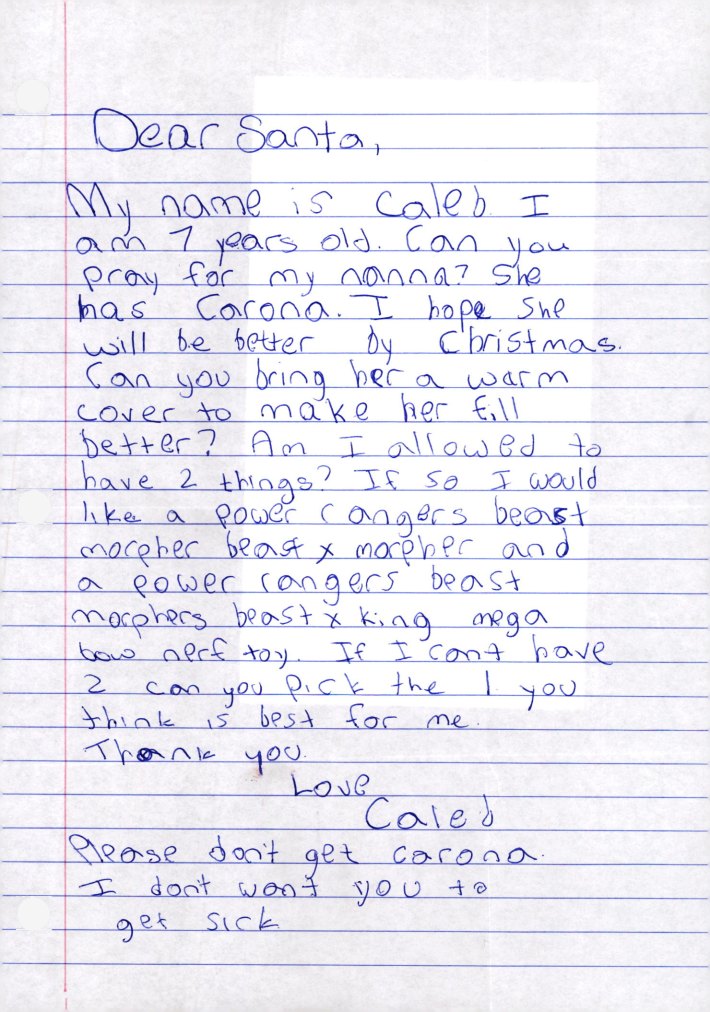

Expressions of dire circumstances in letters to Santa predate the pandemic: A letter from World War I tells of an unemployed father who can’t find work as a longshoreman, and last year a young girl asked for a power wheelchair after hers had stopped working. But the proportion of hardship expressed in the letters I read this year was jaw-dropping, and nearly all of it was attributed to the pandemic directly—my parents lost their job, my family member died, we lost our home—all usually followed by some variant of "due to COVID-19." The children's experience of the pandemic was clear as well. Kids asked for masks and hand sanitizer, and reminded Santa to wear a mask. Others wished for Santa to simply end coronavirus entirely in place of a gift. Many asked Santa how he was dealing with COVID-19, and wondered if he would even be able to stop by due to quarantine.

One recurring thread was a strong dislike for online school, of staying inside so much and missing their friends. Salim asked Santa for “going back to school so I won’t be lonely and sad any more … I haven’t been doing so well mentally. The reason I haven’t been doing well mentally is because I have been doing ONLINE SCHOOL, in my opinion is the worst thing ever because the good parts of school are gone and the bad parts still remain so I have been feeling lonely.” Eight-year-old Melody told Santa, “I am not in school because of the virus, I hope everybody is good because the virus is horibil.” Julian wrote, “Due to some weird sickness that has been going around I cannot go outside and see my friends.”

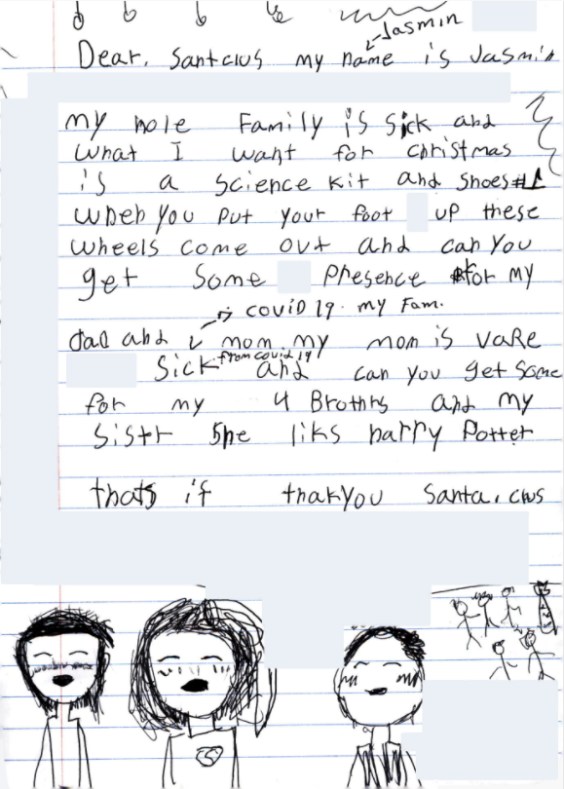

For others, COVID-19 took up even more space in their lives.

Le’Aona wrote: “My grandpa and uncle died from Covid-19. This virus is never going to go away even though I hope it does. My mom is so sad…”

Johny wrote: “Mom lost her job and since grandpa die due covid she spend all her savings in his cremation expenses.”

Keth wrote: “This year was very hard for my family, my dad die due to covid and now my uncle is very sick with covid also. Mom is to down since dad died, she also lost her job because the restarant where she used to work closed…”

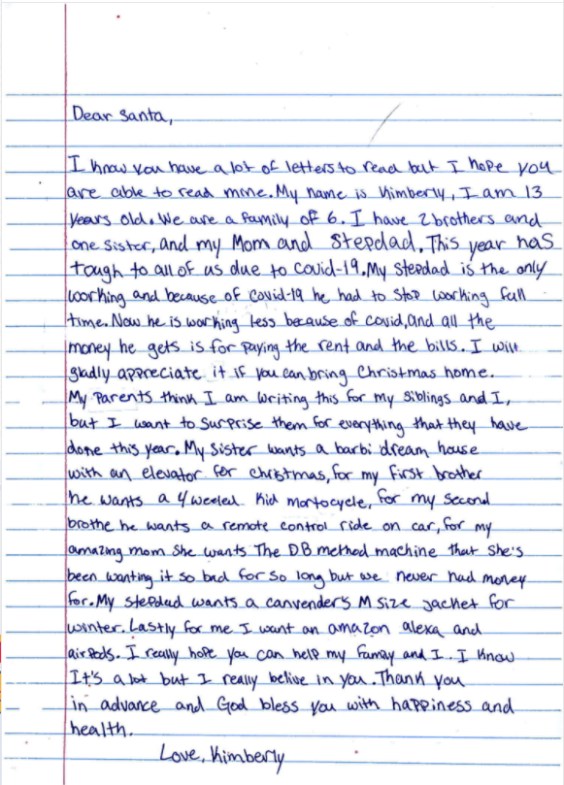

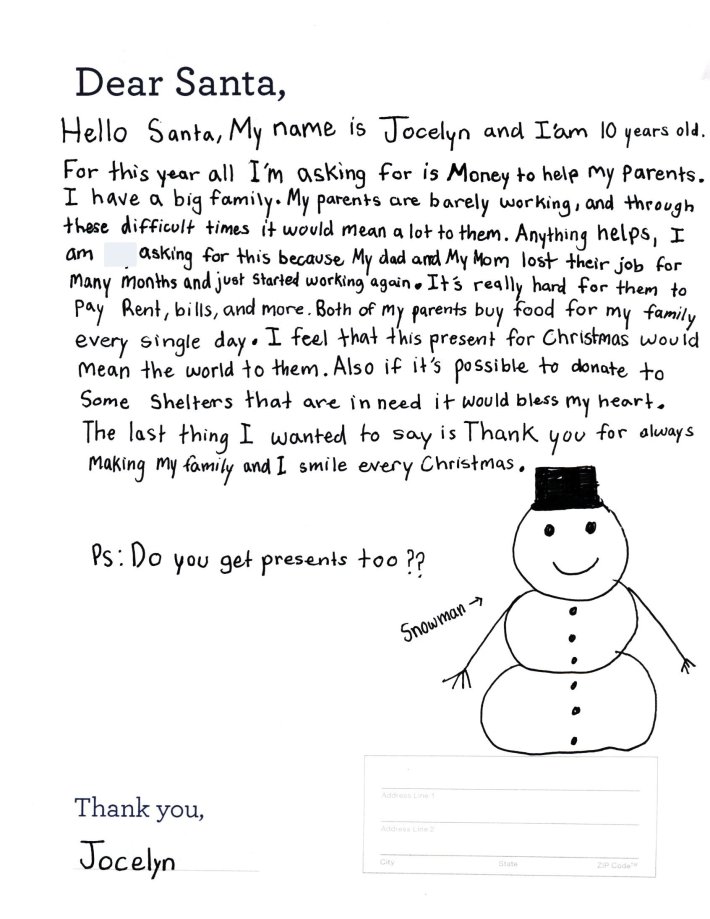

Kids facing financial hardship often asked Santa to help their parents and family as a whole, in lieu of gifts for themselves. "This year has been really rough on my family so i hope you get this letter in time," Leanne wrote. "My mom has been very stressed and depressed over the holiday this year. She lost her job because she had covid and she wasn’t able to afford new school clothes for my sisters and I."

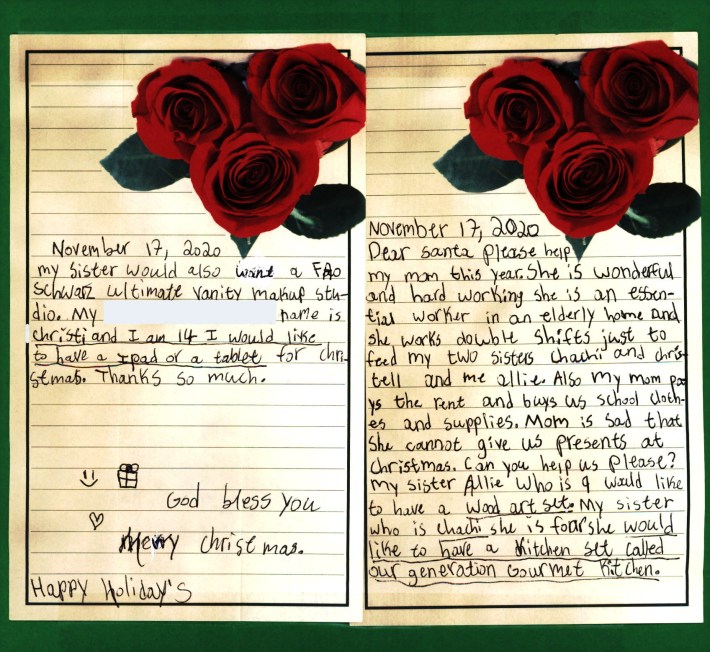

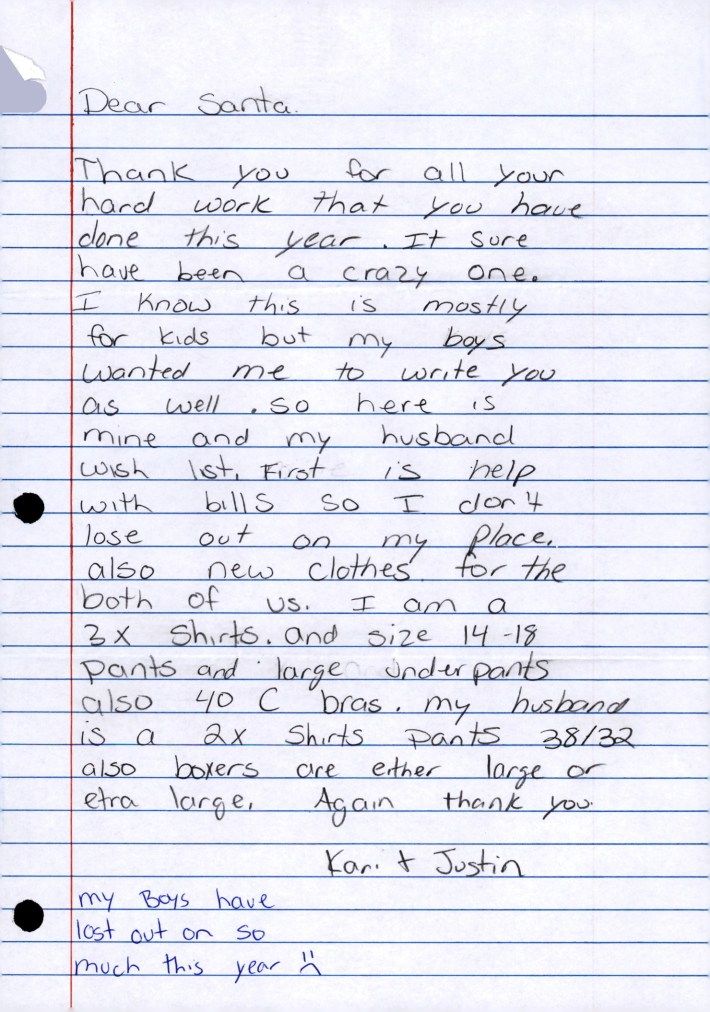

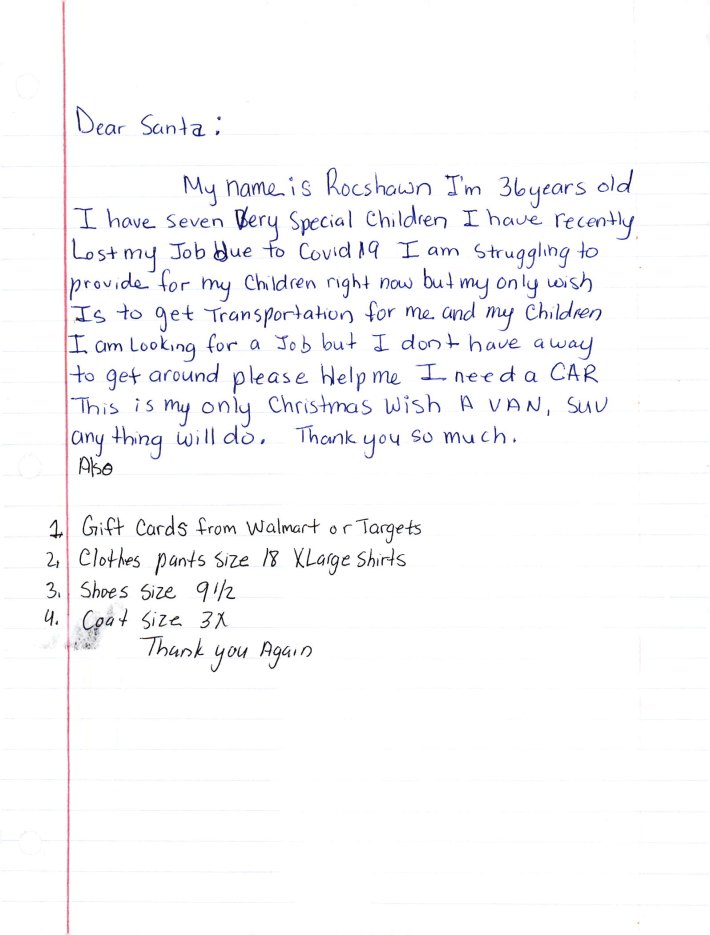

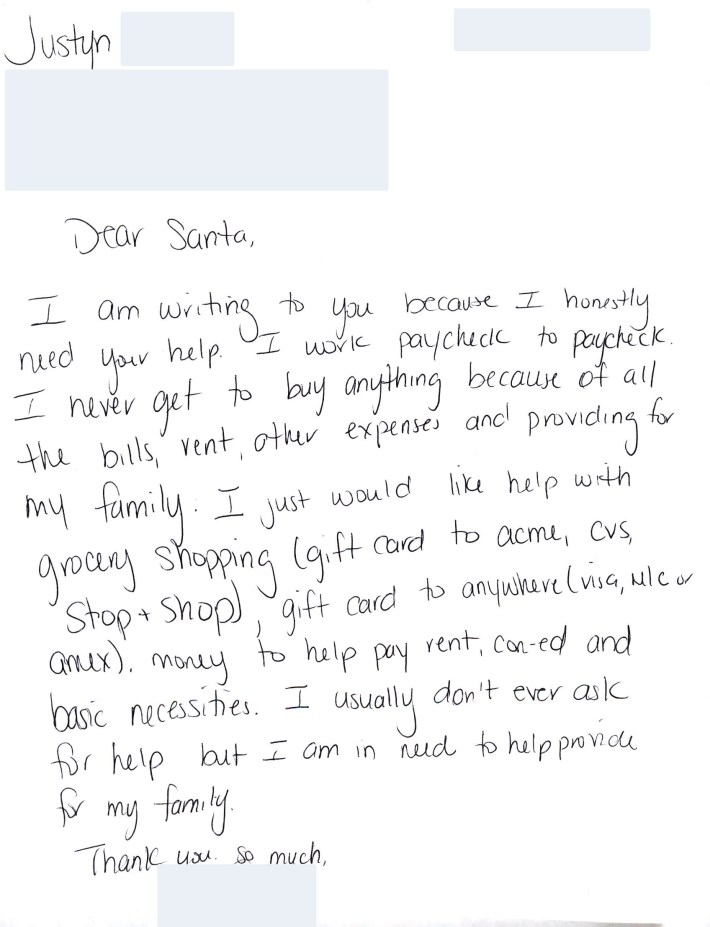

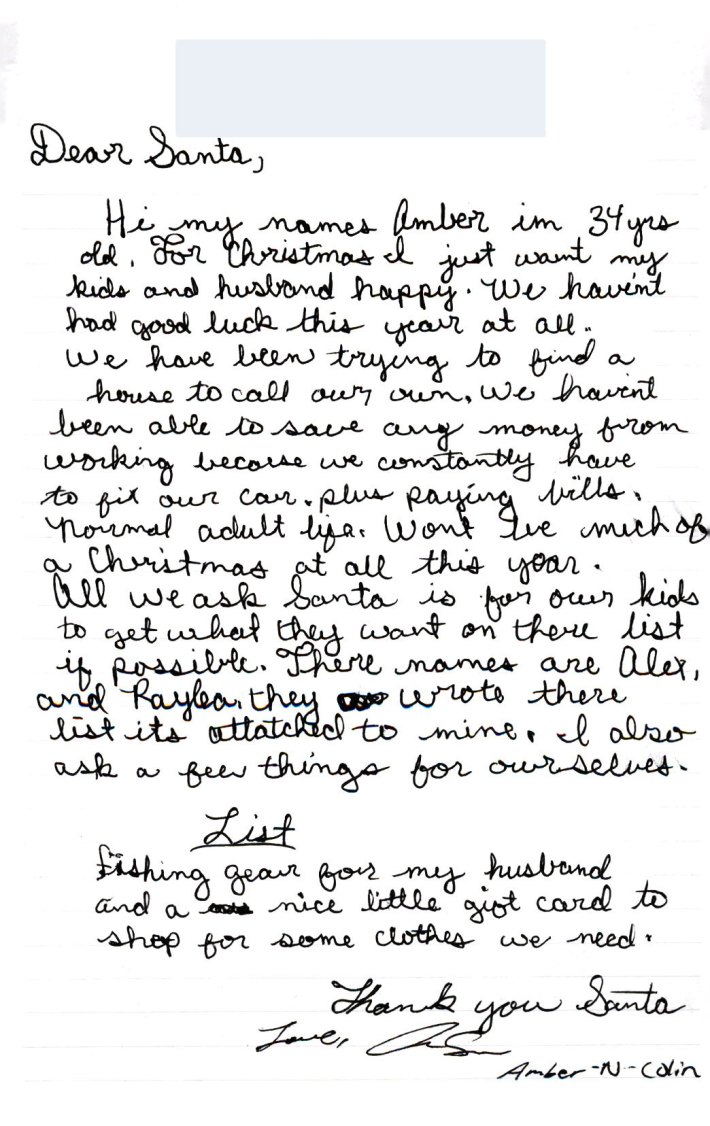

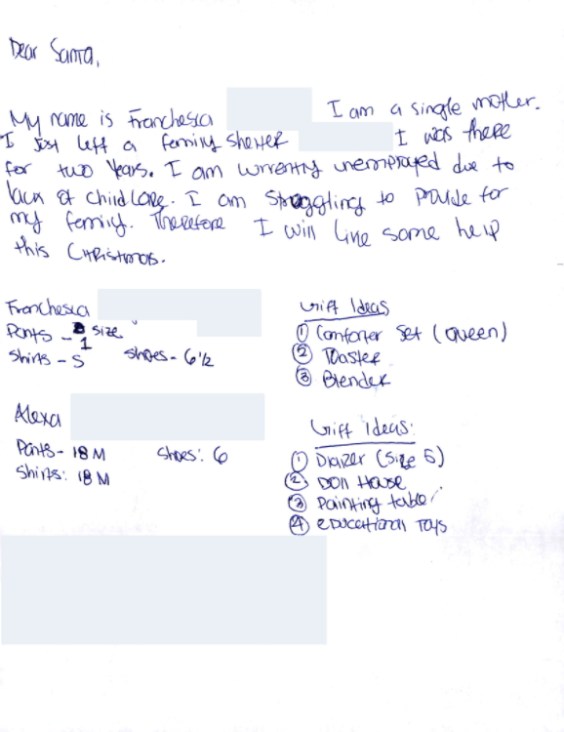

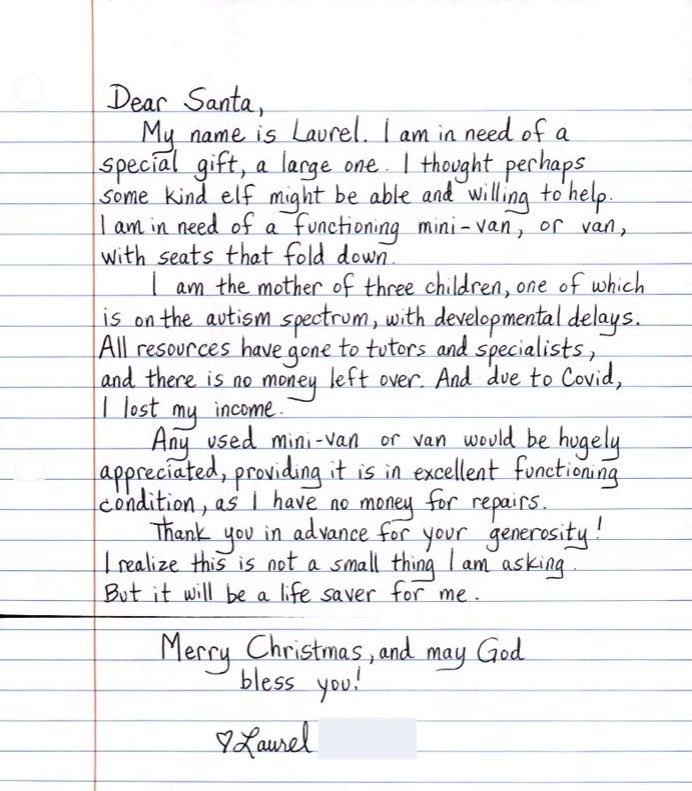

Not only children wrote to Santa. Of all the letters I read, some of the saddest were from desperate parents struggling to provide their families with any kind of Christmas, and more often than not seeking material necessities. Some of these letters felt like personal catharsis, a therapeutic letter in a bottle set out to sea, while others read like they were written with an awareness of Operation Santa and hope for a lifeline. Poor people in America, with no strong institutions to support them, had to turn to Operation Santa to plead for the basic needs of their children.

COVID-19 has gutted the American working class, particularly in households with children. In September, one out of every five kids in America was living in poverty. Approximately one out of every three experienced food insecurity this year.

The economic burden on parents of young children is enormous. In late August, over half of adults in households with children reported loss of income since the start of the pandemic. This year’s high unemployment did not need to lead to millions of suffering kids; getting people to stay home is how to end a pandemic. But in a country with threadbare welfare institutions, not working could mean being put out on the street or going hungry. Nearly one in five adults with children in their household reported being behind on rent. In November, over 13 million parents in a household with children reported that they sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat. Working-class parents are forced into an unwinnable position: Stay home and risk destitution, or go to work and risk infection.

The government's response to COVID-19 has been an unjustifiable failure. The last federal aid money dried up in July, and even though eight million people (including 2.5 million children) have fallen into poverty and cases have exploded across the country, the government has yet to pass another relief package. This level of suffering is needless and concentrated on the working class. While America experiences the fastest rise in poverty in the nation's history, the stock market is setting record highs. The country's 651 billionaires have profited nearly a trillion dollars since the pandemic began–enough money to write a check to everybody in this country for $3,000, more than double the amount sent out by our own government. That the redistribution of this money isn’t taken seriously by politicians or even presented as a reasonable idea within the vastness of America’s mainstream media shows the appalling priorities of this country. While people wither away without aid for the fifth month in a row, this month the Senate came together and successfully passed a $740 billion defense authorization.

The current conditions in America make Operation Santa less of a merry celebration and more of an accidental mutual aid group. To intercept the letters children have written to a mythical being they’ve been led to believe can create any toy in the world for them, to open the letters and find that they have been compelled to follow the obvious logical conclusion, that Santa should be able to make mattresses or food or money instead: There is no joy in this.

In a world of guaranteed food and housing, where the basic materials needed to live a dignified life are available to all, Christmas would be unburdened. It could become what its celebrants want it to be: a time for merrymaking and joy for all, for fuzzy bathrobes, puppies with real hearts, and Fraggle Rock in three languages. But until then, Operation Santa will function as a way to show who gets left behind.