Moments of social and political unrest are moments for compiling reading lists. Or at least that’s the impression I’ve gained while working in American bookstores. There is something intuitive in the impulse to reach for a book during times of heightened societal tension, the impulse to seek out more information, to be enlightened by some meaningful measure beyond cursory understanding. Though, to characterize any point in time as a single “moment,” as some discrete and new era of history rather than a newly spotlit continuation, is one of the drawbacks of a reading list. Turning to a book at a time when it’s called for is a matter of conspicuous consumption and also convenience.

When I’m asked for a recommendation on a political subject by a customer, I try not to discourage anyone from pursuing their interest (though I’m probably nicer to them if I feel they have good intentions). Though I do try to suss out whether their intentions reach beyond simply buying a book and never reading it. There is no totalizing thing to bookselling (other than the usual grievances of working retail), but this might be one of the more common: an ever-constant question in my head, “I see you’ve bought this, now what?”

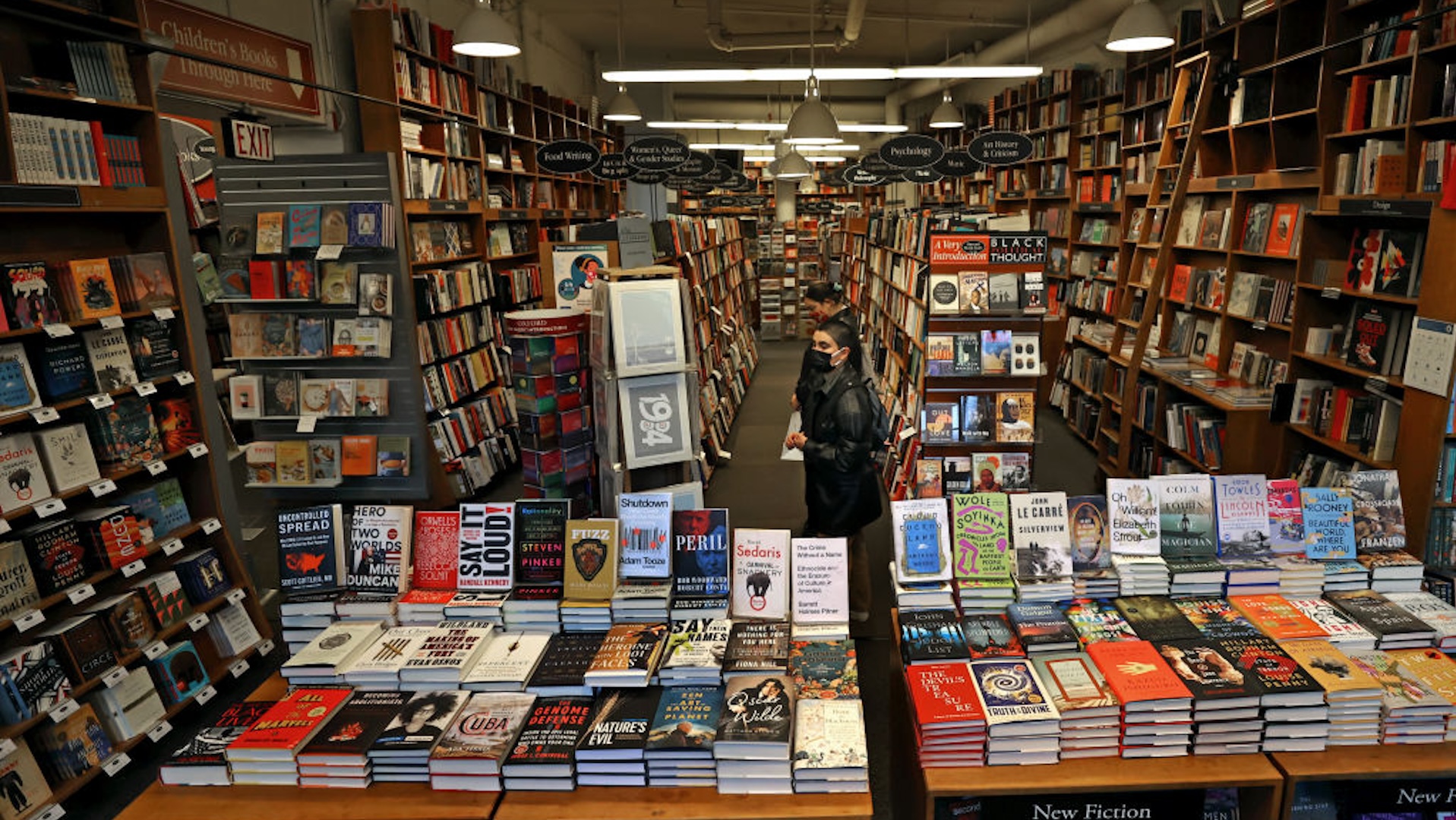

Since Oct. 7, the “this” has been a book about Palestine—a history of, or a treatise on, or a novel from, or an academic discourse surrounding. National and international conflict is good for book sales. We saw much the same thing in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd. And even further back, two terms ago, when Trump took office and the attendant pushback from the media and other institutions was characterized as “resistance.” In 2017, a not-insignificant amount of attention turned to bookstores as sites of political activity, maybe too often labeling mild public statements about democracy and fascism as actual activism. That year Veronica Esposito, writing in LitHub, claimed, “A bookstore is an embodiment of a community’s values. Looking over its holdings is as personal and intimate an encounter as walking into a friend’s home for the first time and sizing up their bookcases.”

What’s particularly funny about this statement is that the home bookshelf can be as neurotically curated for public aesthetic consumption as any social media profile. Oftentimes, the two feed off one another. As for the idea that a bookstore—by which Esposito means the platonic ideal of a neighborhood indie—is a bastion of community values that houses “the food a society wants to feed its mind,” well. Esposito is not wrong, but she’s not right in the way she thinks. Such food is often slop, and the mind being fed is often bifurcated and unfocused. It’s not that independent bookstores aren’t good, that books aren’t lightning rods for expanded thought or sustained intellectual inquiry, or that meaningful encounters between customer and bookseller don’t happen. It’s that the fetishization of reading as a means toward easy empathy, and of bookstores as hallowed temples of freedom and knowledge, obscures two simple facts: that in order to keep the lights on, even the small places will sell what they must, whether virtuous or not; and that there is no real way of knowing if the book that gets sold is a book that gets read.

The ongoing assault on Palestine offers a handy window on these truths. As the death toll continues to rise, as public officials hem and haw while tossing warheads and capital to Israel, an international movement of Palestinian solidarity and consciousness-raising has flooded daily life, including the bookstore. I’ve worked at the same shop for more than five years. Our staff is small, and we generally have a fair degree of creative control when it comes to displaying certain titles. My store had already kept a few books about Palestine stocked well before the Hamas attack. In mid-to-late October, I began frontlisting The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine by Rashid Khalidi and Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by Marc Lamont Hill and Mitchell Plitnick in the area of the store normally reserved for new releases.

This wasn’t a bold act on my part. I knew customers would eventually be looking for books on the subject and that, if they asked, I’d point them to either leftist works or those written by Palestinians. Was I manifesting Esposito’s conception of the bookstore as an expression of a community’s values? Maybe. But I was also reacting to the lessons the previous five years had taught me about supply and demand in times such as these. Sometimes those times align with your views; most of the time they don’t.

Almost immediately, two semi-predictable things happened. First, the books on Palestine that were frontlisted sold out. We only had one or two copies of each so, on its face, this didn’t necessarily signal a burgeoning demand. But the buyer for our store reordered large quantities of each title so we could properly display them in big stacks. Second, before the store received these larger quantities and we were still only displaying one or two copies, those books started going missing. This sort of thing happens a lot: people steal books (for a long time, it was Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus for some reason), or they misshelve them in the wrong section, or they accidentally walk off with them in their bag. Still, it seemed an oddly consistent phenomenon that most if not all of our books about Palestine, frontlisted or not, were being misplaced. They could be found either in an unrelated area of the store, or seemingly deliberately shoved in the back of shelves where no one looked.

Back in 2017, I worked at a bookstore in New York’s Upper West Side. That same year, Golbarg Bashi’s illustrated children’s book P Is for Palestine was published. Initially, Bashi coordinated a reading at my bookstore, back then a branch of Book Culture, now a sterile satellite location of The Strand. The ensuing backlash was instantaneous. Our store, its employees, and Bashi were accused of antisemitism and bigotry. Negative Facebook comments surged. My coworkers fielded belligerent, threatening phone calls. The West Side Rag, a bastion of Upper West Side gossip, covered a local rabbi’s stern letter to the store and his call for its owners to publicly denounce Bashi and his support for Palestine. Never one to miss out on the minutiae of city life, the New York Post ran a largely sympathetic piece about the controversy and about Bashi. All this for a book of fewer than 70 pages.

Nothing so obviously ridiculous has played out at my current place of work, though that same animosity is now more widely enacted. Conversations—searching, sometimes angry, blessedly short—between customer and bookseller about Palestine have become common. And people have turned to books to bolster their opinions. What’s disheartening about this tendency is also what’s encouraging: the impassioned desire to understand a deplorable situation quickly, as if to keep pace with every new development. But this frenzied impulse toward immediate mastery of complex knowledge, surrounding in this case an ongoing genocide, flattens its subject. The pursuit of knowledge justifies itself, but when it is spurred by a specific event such as this, its utility is harder to locate. The death and destruction being inflicted on Palestinians in Gaza is displayed every day, all while Israel’s genocidal aims become more plainly stated. Does one really need a perfectly calibrated reading list in order to arrive at the proper understanding of the horror unfolding right in front of their face?

Lauren Michele Jackson, writing in New York magazine during the summer of 2020, highlighted the absurdity and shallowness of anti-racist reading lists and book recommendations. “Aside from the contemporary teaching texts, genre appears indiscriminately: essays slide against memoir and folklore, poetry squeezed on either side by sociological tomes. This, maybe ironically but maybe not, reinforces an already pernicious literary divide that books written by or about minorities are for educational purposes, racism and homophobia and stuff, wholly segregated from matters of form and grammar, lyric and scene.”

Turning to the subject of Palestine at reading-list level presupposes a uniform and digestible monolith of literature. Search “books about Palestine” and a whole range of sites will direct you to well-curated, supportive, and totally undifferentiated lists of titles that represent the same range Jackson wrote about, except without recourse to genre, time period, or area of focus. Khalidi’s The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine might be a fine place to start, but, assuming a reader starts and finishes it, what comes next? People follow their intuition, the opinions of others, the twinge of a moral call, but when the fervor for or against something cools, that’s usually the end of it. Imagine the ideal politically motivated reader exiting the ideal politically motivated bookstore. What is the next scene? Does the image of a protest come to mind? Shouted voices and locked arms? Immediate contrition from politicians? World peace?

I don’t say this to be flippant. Those images offer comfort because they have real-world precedent, enacted by ordinary people struggling for visibility and justice long before the wider conversation found them and long after it shifted to other things. But such change, such intentional and disruptive action, doesn’t happen because enough people finally read the right books. Those movements are born of political organization and solidarity of the same variety, if not purpose, that motivated the backlash against Bashi in 2017, when the word “Palestine” was not already being spoken on the news every night. The rush towards books at the peak of a crisis can spark individual minds, but a movement that succeeds must kindle and burn long before and after the reading lists are compiled and completed.

It’s been a little over three months since the bombing in Gaza started. New solidaristic groups calling for boycotts and a ceasefire, like Strike Germany, continue to pop up regularly as the death toll in Gaza surges. Books on the history of Palestine continue to sell steadily at our store. If hearts and minds have changed because of this, that’s a good thing. But Palestine needs more than changed but idle minds. It needs more than outraged feelings. It needs more than experts. Reading is one place to start, but it’s only a start.