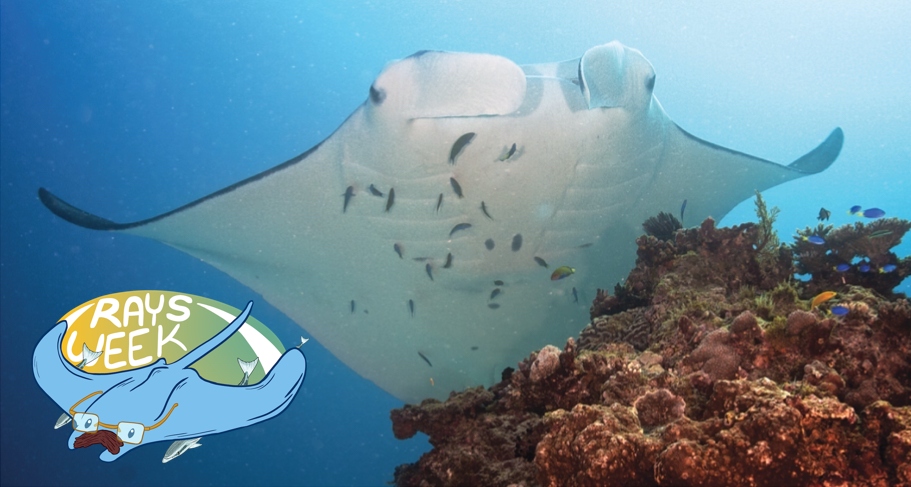

The adult golden trevally is not to be trifled with. The silver-and-yellow fish, which grow longer than a baseball bat and weigh as much as a toddler, are top predators on the reef. But younger, snack-sized trevallies lack this bodily protection, and often use other animals as shields from predators. Babies sometimes find harbor under the umbrella of an unwitting jellyfish, and the yellow-and-black juveniles school around bigger fish, such as manta rays, like a swarm of bees.

The manta rays do not seem to mind the young fish. The juvenile golden trevally is just one of a manta's many groupies, some of which are more intrusive than others. Trevallies and pilot fish swim beside mantas for ephemeral spurts, apparently using the rays as a shield from those that would eat them, or from those they seek to eat. But remoras latch on for good using highly evolved suction disks on the top their heads. For these species, a manta ray is like an island—rare sanctuary in open waters. Imagine that: to be so big and gentle that your body becomes a kind of home for fish.

These tiny companions are not new to any person who has seen the enormous rays gliding undersea. Fishy entourages accompany other giants of the sea, such as whale sharks and regular sharks and regular whales. But scientists have only recently begun to investigate these communities in manta rays—which species accompany different manta ray populations, who benefits from these relationships, and how all this information could help conserve manta rays around the world. "My biggest question is, how important is it for the manta ray and other species?" asked Aldo Alfonso Zavala Jiménez, a project leader at Proyecto Manta Pacific Mexico, which surveys oceanic mantas and the environmental qualities that influence their presence in Bahía de Banderas, a bay on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

Traditional symbiosis refers to physically close, long-term associations between species, such as the kinships between a clownfish and an anemone, or the fluffy crab that wears a sponge as a hat. Remoras have a well-known symbiotic relationship with manta rays and other big fish, as they spend much of their lives on a host—though they can get an occasional slight change of scenery by moving around on said host, surfing along the skin for prime spots protected from more turbulent water. Remoras "are really smart creatures, they choose the areas where the drag is less strong," Zavala Jiménez said. "They have a lot of knowledge about hydrodynamics." And even remoras get some alone time. The sharksucker remora is a shallow-water species, so during a reef manta ray's regular 650-foot dive, the sharksucker will pop off and loiter in the light until a new reef manta host emerges from the shadows.

For a remora, there are huge benefits to living atop a manta, including protection and a free ride. Manta rays are also filter feeders, swallowing clouds of tiny creatures that can sometimes clog their gills. When this happens, the mantas vomit to clear their gills. "The remoras start eating all the puke that the manta has thrown away," Zavala Jiménez said.

Still, an interspecies relationship need not be long-term for it to be a useful one. Researchers are investigating the more ephemeral associations between a manta ray and its many casual acquaintances: the kinds of fish a ray might encounter briefly on a crowded reef and bump into only occasionally. And though these interactions may not offer any benefit to the manta ray, they can be a boon to the littler species. "Even if it's really short-term," Zavala Jiménez said, "like for three minutes or half an hour, I believe that it has a lot of importance in the life cycle of the fishes."

In a 2021 paper in the journal PLOS One, a group of scientists from the nonprofit the Manta Trust and the University of Bristol described some of these associations from surveys and citizen science sightings of reef manta rays and oceanic manta rays in the Maldives. The researchers were aware of a few studies on manta rays and remoras, but wanted to investigate "hitchhiking species that aren't part of the remora family," Aimee Nicholson-Jack, an author on the paper and a researcher at The Manta Trust, wrote in an email.

While sharksucker remoras and giant remoras were the most common species spotted on the Maldivian mantas, the researchers identified a slew of more casual companions, including trevallies, pilot fish, red snapper, cobia, and the tubular Chinese trumpetfish. Many of these species only hung around the mantas as juveniles. "These hitchhikers utilize marine megafauna as shelter until they are mature and able to occupy different habitats or defend themselves against predators," Nicholson-Jack said. For these young fish, mantas can be one of several possible bodyguards. In the open sea, pilot fish often swim alongside oceanic whitetip sharks. Nearer the coast, golden trevallies swim with dugongs and tiger sharks.

The roles in these communities are broadly similar around the world, according to Joshua Stewart, a conservation ecologist at Oregon State University Marine Mammal Institute who founded Proyecto Manta Pacific Mexico. "What's interesting is that in different parts of the world, it's often different species that are fulfilling those roles," Stewart said.

These rotating casts of characters often congregate around cleaning stations—reefside spots where mantas and other animals make their bodies into a banquet for tinier, parasite-munching animals. In the Indo-Pacific seas, cleaner wrasses will bite the parasites off of mantas. But off the Revillagigedo Islands of Mexico, the Clarion angelfish, which is endemic to the region, is the only cleaner around. And in the Gulf of California, the King angelfish can also be spotted cleaning mantas. "It sort of tells us that there are these fundamental services that need to be provided," Stewart said. "Regardless of where they are, those services will be provided by somebody."

In Bahía de Banderas, researchers have observed that injured manta rays often have more chances to interact with these fish communities, according to Iliana Fonseca Ponce, a project leader at Proyecto Manta Pacific Mexico. "We have seen injured manta rays that glide really close to the shore in look for cleaner fishes, or other kinds of fish species that eat the dead skin of their wounds, and that helps them to heal," Zavala Jiménez said, adding that sabertooth blennies often lead this wound care.

Investigations of these communities have also complicated common beliefs about manta rays and remoras living in mutually beneficial symbiosis. Scientists long assumed the remoras eat external parasites off the mantas. But the closer researchers looked, the more it seemed the remoras can also inconvenience or even harm the rays. Nicholson-Jack and colleagues observed instances where the remoras' adhesive discs left persistent damage and scarring on mantas' skin, and deforming injuries where little remoras snuck inside the manta's gill slits. In Bahía de Banderas, Zavala Jiménez has seen remoras squabble over "territory," meaning the same manta ray. This, at least, does not bother the ray.

In dives off of Isla de la Plata, a small island off the coast of Ecuador, mantas can be carpeted in remoras. "We've seen mantas with like 100 remoras on board," Stewart said. A manta may not mind a remora or two on their back, but 100 remoras means a huge amount of extra weight and extra drag, veering from symbiosis towards parasitism. Sometimes these remoras have gaping wounds, evidence of the manta rays attempts to dislodge the freeloading fish. "The researchers who work there say that they see the mantas basically, like smash themselves against rocks, to try and dislodge the remoras who refuse to come off," Stewart said. "When I was down there a few years ago, I saw a remora that looked like it was barely alive. Its head was smashed open, but it was still sucking on."

In Bahía de Banderas, the primary threats to mantas are fishing nets and boat strikes, which leave many of the wounds that sabertooth blennies help clean. Zavala Jiménez and Fonseca Ponce are surveying the mantas and the species that live alongside them in order to help local fishermen avoid entangling the large rays in their nest, as well as share the knowledge of the role the rays play in marine ecosystems to promote sustainable tourism and conservation. "It's another kind of relationship that must be understood to have a better picture of why the manta ray visits the area and how the other species are important for the manta ray," Zavala Jiménez said. "We want them to know the manta ray and learn to love the manta ray." In this, and many other ways, a manta ray is never truly alone.