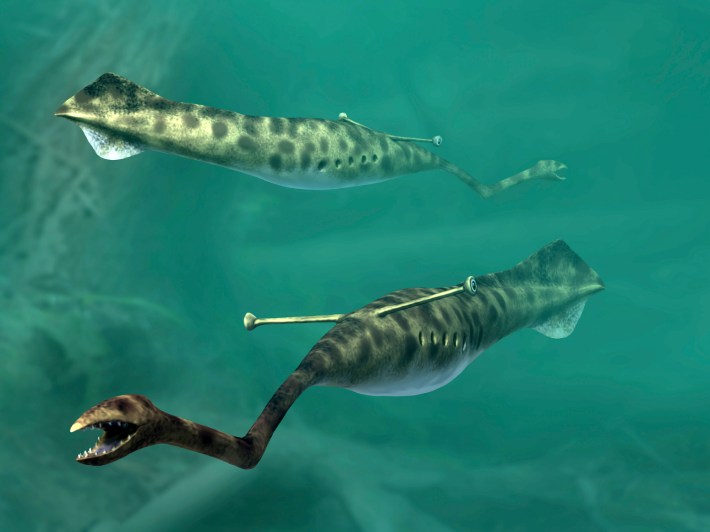

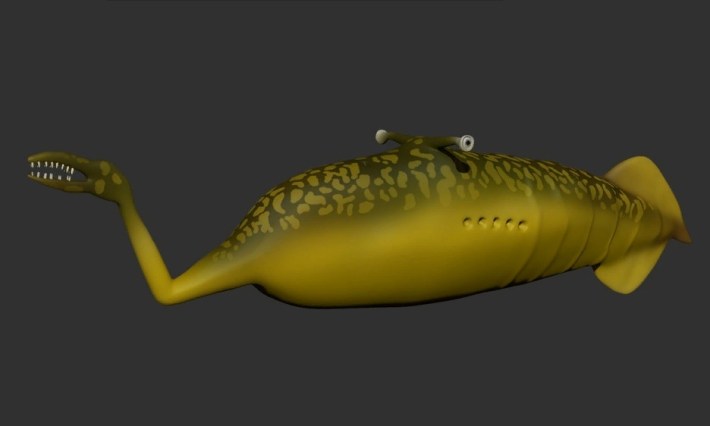

For a creature harangued with accusations of being "problematic" and a "monster," the Tully monster was actually quite delightful. Its body was long and soft like an overripe cucumber, tapering into a spade-shaped tail fin at its rear end. On the creature's front end, where one might expect a head, its body instead tapers into an appendage not unlike an elephant trunk and tipped with a toothy, grasping pincer. And as a baffling, final garnish, a pair of eyes on either end of horizontal stalk sit atop the creature like a weird oar.

This 300-million-year-old creature has been mysterious since it was discovered decades ago. It is an animal without obvious ancestors or descendants, an organism apparently out of place in any place or era or, well, situation. It is the kind of fossil that makes me wonder if, one day, it may be unmasked as a hoax; the creature's neck-like snout even convinced a Loch Ness truther that Tully was Nessie's ancient ancestor.

For decades, scientists have tried to jam the Tully monster into the tree of life. People have, at various times, suggested the creature was a worm, or maybe a lobster, or some kind of slug, or, perhaps a fish? Different scientists have flip-flopped between calling the creature a vertebrate or an invertebrate, and each new theory inevitably leads to triumphant headlines declaring that, at last, the mystery of the Tully monster had been "solved." The latest of these headlines arrived this week, accompanying a new paper published in the journal Palaeontology that aims to swing the vertebrate-invertebrate pendulum back favor of the spineless.

Over the years, I have followed the mystery of the Tully monster and other "problematic" fossils as they have been ostensibly solved. Just last year, the mystery of the "alien goldfish" was solved, the mystery of the "skeleton tubes" was solved, and the mystery of the "half-billion-year-old creature with no anus" was solved. With so many of these stories floating around, it is easy to lose sight of what, exactly, is being "solved" here. The obvious, and most common answer, is taxonomy—where each of these creatures can be classified on the sprawling tree of life. The alien goldfish was a mollusk; the skeleton tubes belonged to an ancient tube-building jellyfish; and the creature with no anus was an ancestor of spiders and insects. This question of classification forms the titular mystery of the Tully monster: What kind of animal was it?

The Tully monster roamed the tropical coastal waters of what is now Illinois, along with more legible relatives of modern shrimps, jellyfish, sharks, and sea cucumbers. The species was discovered in 1958 when Francis Tully, a retired pipe fitter and amateur paleontologist, found an ironstone nodule that had cracked in two. The nodules are commonplace in Mazon Creek, where millions of years ago they hardened via chemical reactions around dead animals and plants and were later discarded by coal miners in fossil-laden heaps. This particular cracked ironstone contained the impression of a blimp-like creature that Tully had never seen before. He brought his find to the Field Museum, where it also stumped the paleontologists; it was soon nicknamed the Tully monster. In 1966, Eugene Richardson, the museum's curator of fossil invertebrates, described the fossil in Science and dubbed it Tullimonstrum gregarium, simply latinizing its nickname.

Years of collecting have unearthed thousands of Tully monsters, ranging in size from a few inches to nearly a foot long. The creature became the state fossil of Illinois, as well as the face of many U-Haul trucks. As Tully monster's fame has grown, so have attempts to classify it. In his 1966 description of the fossil, Richardson went little further than "worm-like." In 1979, a geologist suggested it was an "aberrant member" of the molluscs, perhaps something like a sea snail. About a decade later, a reanalysis suggested the Tully monster's closest relatives were either sea snails or extinct and weirdly toothed eel-like creatures called conodonts. Somewhere along the way, another paleontologist concluded the fossil must have been one of two unrelated types of worm.

All of these identifications seemed plausible, but somewhat impossible to prove. The ironstones from Mazon Creek preserved beautiful silhouettes of even the most diaphanous creatures but no organic matter from the animal itself. But in 2016, two unrelated papers, coincidentally both published in the journal Nature, came out with new lines of evidence suggesting the Tully monster was a vertebrate. One team of researchers uncovered microscopic pigments in the eyes of Tully fossils, examined them under a scanning electron microscope, and found a carpet of "meatball" and "sausage" shaped pigment granules—a unique characteristic of vertebrates. The other team reexamined a white streak running down the middle of the Tully monster's body that was previously interpreted as the creature's gut tube—strange, considering the other fossils found in Mazon Creek had black gut tubes, and some Tully monster fossils had a black line in addition to a white one. So the researchers identified the white line as a notochord, a flexible rod found only in vertebrates.

The latter group suggested the Tully monster's closest living relative was a lamprey, the noodle-like fish with concentric rings of nightmare teeth. Papers of repute—The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Scientific American—declared the Tully mystery solved at last, and people flocked to the streets to bang celebratory pots and pans and toot celebratory vuvuzelas.

But nothing from 300 million years ago is ever truly settled, and a year later a group of thoroughly unconvinced paleontologists fired back in a paper in Palaeontology titled in part "The ‘Tully Monster’ is not a vertebrate." It pushed back against claims in both previous papers, noting lampreys have been found in Mazon Creek that don't resemble the Tully monster, and citing the many magnificently complex eyes of the invertebrate kingdom—just consider the octopus! "If you’re going to make extraordinary claims, you need extraordinary evidence,” Lauren Sallan, a paleobiologist at the University of Pennsylvania and an author of the Palaeontology paper, said in a press release.

In the years since, the papers have kept coming. A 2019 analysis of Tully monster eyes in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B threw a hat in the invertebrate ring, and a 2020 soft tissue analysis in Geobiology threw a coin in the fountain of vertebrates. And now a 2023 paper creating a 3D model of the Tully monster in Palaeontology has joined the ranks of would-be mysery-solvers, arguing the creature was an invertebrate due to segmentation in its head region.

In the opening of the beloved musical Fiddler on the Roof, the villagers of the Russian shtetl of Anatevka sing a song about their traditions, aptly called "Tradition." The song reaches an iconic climax when the villagers, divided over the identity of an ungulate recently sold at market, begin to shriek "Horse! Mule! Horse! Mule!" before returning to sing together once again about tradition. This is how I feel every time the Tully monster mystery is announced, breathlessly, to have been solved once again. The headlines read like fact, as if the debate were actually settled. The Tully monster didn't have a spine after all! The Tully monster's eyes prove it's a vertebrate! True nature of Tully monster revealed! Of course I want more, unending, papers about this unusual creature. The pursuit of the Tully monster's true role in the story of life on Earth is an important question, and one that may indeed be answered eventually with new tools, new fossils, or even new researchers. This is the grand tradition of science: inching closer and closer to our best approximation of truth.

But as I see it, taxonomy is not the only, or even most interesting, question in play here. Knowing whether the Tully monster did or did not in fact have a notochord does not solve the mysteries of a truly bizarre creature that once swarmed the submerged canyons of Chicago like Cubs fans in 2016 (a huge year for Illinois creatures, past and present). I could spend hours speculating how the creature's dumbbell-shaped eyes may have scanned the tropical waters for prey, what colors adorned its soft and perhaps slimy body, and, most importantly, all the ways it used its bendy mouth-snout—for food, certainly, but any elongated snout raises a host of evolutionary questions. A living being's existence is about so much more than who its relatives are. And the closer we come to the truth, the more we are reminded of the unfathomable gap of time.

Anyway, see you next year when the mystery of the Tully monster is solved yet again, and BYOV (bring your own vuvuzela)!