The 110th Tour de France kicks off this Saturday in Bilbao, with 22 teams, 176 riders, 3,404 kilometers of racing, 21 stages, over 56,000 vertical meters of climbing, a scant 22 kilometers of individual time-trialing, and one rider crowned champion under the Champs-Élysées in three weeks' time. Nothing in the cycling world matches the Tour for brutal spectacle or pure dramatic heft, which is why it's the race on the calendar that breaks out into the mainstream.

Oddly, being a big-time cycling sicko has made me appreciate the Tour even more with each passing year, especially as the era of Team Sky's iron-fisted dominance over the peloton has given way to a new crop of young hotshots. There are other three-week Grand Tours, in Italy and Spain, each of which has something special to offer. Even though they are similar in distance and difficulty—more because the Giro d'Italia is snowy and the Vuelta a España is scorching—they pale in comparison to the Tour.

The reason is simple: The world's best riders are all here in France. Any rider getting a Tour spot on any team is a huge deal, and unlike the Giro, the Spring Classics, or other one-week races like Paris-Nice, the field is unbelievably stacked. Winning one stage will change the course of a rider's career; winning the whole thing will change a rider's life.

The Tour's scale is so fun because most riders there have different but occasionally overlapping goals. Some are there to contend for one of the four jerseys, some want a stage win and have targeted one of the 21 opportunities for months, some are only there to ride for their teammates, and some just want to survive to Paris intact after serving as water-bottle delivery boys. To make sense of all of these Tour plotlines, I have conducted an interview with a cycling expert below.

Sorry, but isn't Bilbao in Spain? I thought this was a Tour "de France"?

The Tour loves to kick things off with a few little introductory stages in nearby countries. In the past decade, it's started in France four times, and the UK, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and now the Basque Country. Unlike all those other Grand Départs, the racing in Euskadi will be difficult and intriguing from the start. The Tour tends to begin softly, with a short prologue time trial or handful of flat stages, before ramping up by the end of the first week. Not this time!

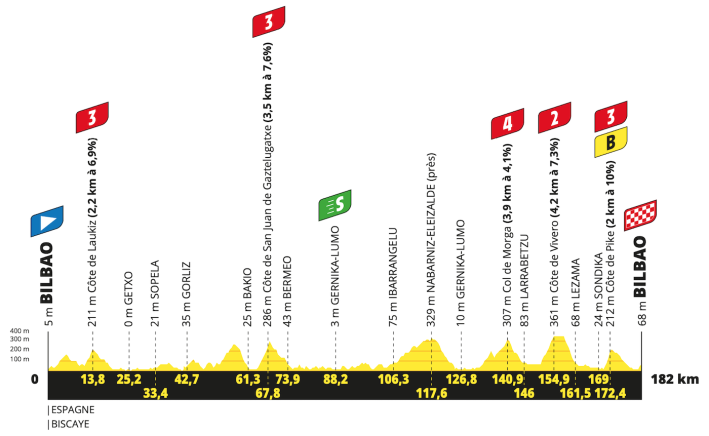

The Tour of the Basque Country has the notorious reputation as the hardest one-week stage race of the season, and this year's Tour de France will traverse many of the same roads. The first stage begins and ends in Bilbao, with 3,300 feet of climbing and the nasty Cote de Pike right at the end. This means the big favorites will fight it out for the stage win and the first yellow jersey of the race on the opening day, which is quite rare. Look how spiky this is:

What am I looking at here?

The red numbers indicate what category a given climb is, with distances and average gradients also listed. Four is the lowest category, and the scale goes up to and then beyond one, to the famed, imposing hors catégorie (which translates to "beyond categorization"). The categorization matters, but steepness is the thing to look for. Some HC climbs are 25 kilometers but on military-grade roads at 5.5 percent or so. That's more difficult but critically less selective than a Category 2 kicker like the Cote de Pike. It's harder to maintain tempo and respond to aggression on a slope like that, especially on the first stage when every team will be trying to launch their guys.

Cool, so the first stage is hard.

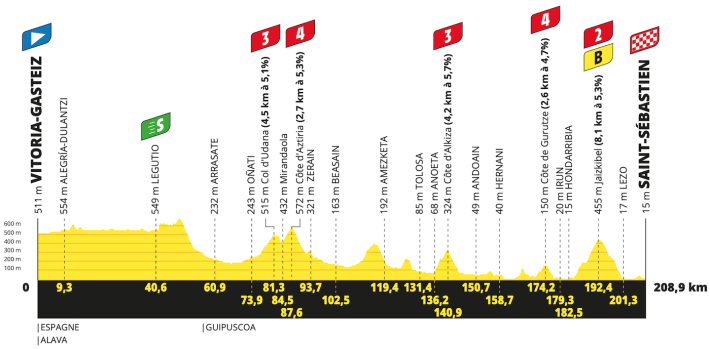

As is the second! Stage 2 sees the peloton trace some of the one-day Donostia San Sebastian Klasikoa route, finishing a few kilometers after the summit of the even more difficult Jaizkibel (though the peloton will climb it from the east, the opposite of the Klasikoa). Stage 2 is the longest stage of the race, though actually 209 kilometers is not all that long for a longest stage.

OK, sure, Basque mode sounds cool. Txakolina and pintxos and all that. But when do they get to France?

Stage 3 departs from Spain and finishes in Bayonne, France on a stage for the sprinters, though, again, the 2023 route once again shows its atypicality here. Usually, the Tour moves north-to-south, follows some vaguely looplike shape, and ends in either the Alps or Pyrenees before everyone flies back to Paris for a parade. This time around, the race moves in one diagonal line, cutting northeast from Bilbao up to the Alps, hitting the Pyrenees early on, while stopping along the way for little tourlets of France's other three mountain ranges: the Massif Central, the Jura, and the Vosges.

In recent years, the Tour de France has shortened and varied its stages to make for a more exciting product. Gone are the days of foreboding single-day suffer-fests interspersed with pancake-flat days and the odd mid-mountain stage. This Tour starts off with a bang and maintains a steady level of difficulty throughout. Stages are punchier, more unpredictable, inviting riders to challenge each other and take more risks. There are some big highlight stages and 30 climbs categorized as twos or higher (seven more than last year), though no single day is as torturous as last year's Télégraphe-Galibier-Granon tripleheader or 2021's Mount Ventoux deux fois special. What we have is a balanced route that remains demanding for three weeks. Organizers are sacrificing a few days of slow-rolling through sunflower fields in exchange for more exciting racing.

There's a dark side, though. Swiss cyclist Gino Mäder recently died at the Tour de Suisse after crashing on a descent, and his memory will hang heavy over this year's Tour. His Bahrain-Victorious teammates will race for him, stage winners will pay tribute to him, and any time a rider takes a big risk on a descent, the commentators will mention his name. Mäder was a bright light in the peloton, someone who wore the inherent painfulness and loneliness of professional cycling with a rare sense of joy. The Tour is, among other things, a celebration, but Mäder's death is a grim reminder of how thin the margins can be in this sport. Everyone at the Tour is here to push their limits, and the metagame has evolved in the past few years to incentivize taking big risks on the descent. That's even truer this year, with four true summit finishes and just as many descent finishes after selective climbs. Will riders still push themselves just as hard as they did before Mäder's death? Absolutely. Everyone knows the risk, although in the 12 years since Wouter Weylandt died at the 2011 Giro, it was possible to forget the consequences of those risks.

Who's going to win?

While this year's route is a highlight, the real reason why this is the most hotly anticipated Tour de France in a while is the two-man battle for the yellow jersey. With all due respect to the seven or eight second-tier contenders, the 2023 Tour is headlined by the third installment of the Jonas Vingegaard–Tadej Pogacar trilogy. Vingegaard, the 2022 champion, and Pogacar, the winner in 2020 and 2021, are perfect foils for each other.

Vingegaard is probably the best climber in the world, capable of inflicting an otherworldly amount of pain on himself as he vaults up the highest mountain passes at the highest altitudes in France. The gawky Dane looks like a two-wheeled advertisement for VO2 max, his sallow cheeks, avian body, and gulping mouth all highlighting the feats of oxygen exchange that fuel his exploits. The Granon stage I mentioned earlier was the site of Vingegaard's most famous win, where he ended two years of Pogacar dominance and seized the yellow jersey for good.

Vingegaard comes armed with the best supporting cast in cycling, and no matter what Netflix tells you, Wout Van Aert alone is worth two or three riders in non-mountain stages. One might assume then that this year's climb-happy route favors Vingegaard, especially since Pogacar is the superior time-trialist and this year's route features one short time trial with a hill on the course. But Pogacar destroyed Vingegaard in 2021, winning three stages and taking the yellow jersey by 5:20, the second-largest Tour margin of victory of the last 26 years. He's won almost every race he's started this year, including the last five races he's finished. Nobody—not Vingegaard, not Remco Evenepoel, not Julian Alaphilippe—can come close to matching Pogacar's explosiveness on the bike. When he makes moves, they tend to stick. Hair poking out from his helmet, he grins as he dances on the pedals. Pogacar also never leaves food on his plate, as he already has nine Tour stage wins in his career. This year's course, with its varied mountain stages and lack of monster climbing stages, actually suits him better. Pogacar is a wicked descender too, and many stages this year finish on descents, not summits. If he's the sort of rider who wins every time he starts and these are mostly his sorts of stages, why can't he win this year's Tour in style?

The only question mark with Pogacar is his wrist. He won the last five races he's finished, but in April, between the third and fourth win, he crashed out of Liège-Bastogne-Liège early and broke his wrist. Since then, he did return to win the time trial and road race at Slovenia's national championships. Fellow medalists Matej Mohoric and Luka Mezgec are gifted riders and Pogacar smoked them, but he skipped all the big, pre-Tour stage races and we don't know exactly what sort of stage-racing form he is on. Three weeks is a long time. His UAE team is talented but nowhere near as good as Jumbo, which was part of his undoing last year on the Granon stage. UAE boss Mauro Gianetti also said this week that top climbing lieutenant Adam Yates was the team's co-leader, which does not inspire confidence.

Can anyone spoil this party?

There are eight worth mentioning, in rough order of how they're perceived heading into the Tour. Jai Hindley is finally going to take his first run at the Tour de France after targeting the Giro d'Italia for years and winning the 2022 edition. He'll have Bob Jungels and Emanuel Buchmann to defend him in the mountains, and he's shown good form by finishing fourth at the Critérium du Dauphiné. The question with Hindley is whether he really has the climbing legs to stick with the Big Two in the highest mountains. David Gaudu finished fourth last year, and he's the big hope for the hometown French fans. He was flat bad at the Dauphine, but he was strong enough to split Pogacar and Vingegaard for second place at the only stage race the two have both contested this year. Richard Carapaz, erstwhile Tour podium finisher and 2019 Giro champion, finally left Ineos and will lead EF-EasyPost for the first time since his third place behind the Big Two in 2021. The Ecuadorian Olympic champion's form has been pretty inconsistent lately, and his team isn't the strongest, but he's a great rider at high altitudes, and one hopes he learned his lesson about going too hard too early after losing the 2022 Giro to Hindley.

Two-time Vuelta runner-up Enric Mas is a boring climber with a bad team yet an impressive steadiness in the mountains. I don't see him winning a stage or the overall, though it's hard to imagine he doesn't crack the top 10. Jayco leader Simon Yates is an incredible climber on a climber's route who will hope he can have better Tour luck than he's had in the past. Keep an eye on 22-year-old Danish rider Mattias Skjelmose from Lidl-Trek. He just won the Tour de Suisse, and he's had a ton of impressive climbing performances this year. Five seasons ago, you'd throw out the idea of a 22-year-old winning the Tour on their first go, but Vingegaard and Pogacar (and before them, Egan Bernal) have all won the Tour at 25 or younger, and Skjelmose's 2023 has been too good to ignore.

Ben O'Connor had the worst luck of any big contender last year, though like his countryman Hindley, he looked lively at the Dauphine. I'd love to see a strong comeback for him. Finally, 2019 champion Egan Bernal is back! The-then youngest Tour winner ever followed up that success by winning the 2021 Giro, and it seemed the 2022 Tour would finally be the all-out Bernal-Pogacar battle the cycling world was waiting for. But Bernal suffered a horrific crash in January 2022 that left him with severe injuries. It's a miracle he's even back on a bike, let alone racing at a high enough level to contend for the Tour de France. The Tour's first Colombian champ got into the top 10 at the Tour of Romandie this year, and while he certainly will not win the 2023 Tour, it will be great to have him back as he builds to a serious challenge in 2024.

And those are just the General Classification guys!

You motherfucker.

Van Aert is a threat to win any stage he really chooses to go for. Mathieu van der Poel, his principle rival, will be back to duel him on anything that's not too hilly, and Biniam Girmay, one of my favorite riders in the peloton, will look to spoil the fun. These three are classic riders, who will contend in the more classic stages we have this year, as opposed to years past, when the pure big-dog sprinters got around 10 stages to fight over. As for said sprinters, Jasper Philipsen, Fabio Jakobsen (another guy who is lucky to be alive), Dylan Groenewegen, Caleb Ewan, Mads Pedersen, and Mark Cavendish all expect to leave France with at least one stage win. Maybe three of them will, if things get weird. Cavendish is tied for the all-time Tour stage wins record, and this is probably his last shot at passing Eddy Merckx.

Tom Pidcock surprised everyone when he won the Alp d'Huez stage last year, and since Ineos is sending a young, impressively weird squad to the race this year, he'll certainly have the leeway to go for stuff. Italian climber Giulio Ciccone has been balling lately, and you can rely on him gunning for every stage unless Skjelmose really needs help. I would love to see Julian Alaphilippe get back onto the winner's podium this year after he had to sit last year out with an injury, and he just won a stage at the Dauphine. He's always good for a few amazing performances every Tour, and he made me a fan for life when he seized the yellow jersey early in 2019 and kind of accidentally finished fifth. Watch out for Carlos Rodriguez at Ineos as well. The 22-year-old finished seventh at last year's Vuelta in his debut Grand Tour, and he seems like someone who will win a Giro or Vuelta in the next few years. Who knows what will happen if he takes an honest run at the big guys. British rider Fred Wright is also cool. I'll be rooting for him, Pello Bilbao, and all the Bahrain guys as they race in Gino Mäder's memory.

Are there any cool Americans to know?

Sepp Kuss! The Colorado native is Vingegaard's most trusted mountain lieutenant, and he's distinguished himself as the best climbing support teammate in the world over the past few seasons. He's paced Vingegaard at the Tour, helped Primoz Roglic win the 2023 Giro, and when he's been allowed to race for himself, he even delivered a 2021 Tour stage win. Kuss and Brandon McNulty went back and forth fighting each other on behalf of their leaders last year, and while McNulty won't be coming to France after also racing the Giro, it is finally Matteo Jorgenson time.

Jorgenson, a Bay Area native, has been going nuts in his fourth year with Movistar. He won the Tour of Oman, finished second at Romandie, and got into the top 10 at the Tour of Flanders. Most importantly, he's shown an evolution in his racecraft. Jorgenson is a nimble rider with a nice finishing kick, the sort who is ideally positioned to win from the breakaway, and this season he's shown some real tactical skills.

Lidl-Trek rider Quinn Simmons smoked the field at the U.S. Nationals. Like Jorgenson, he is the type of rider who will try to get into breakaways when he's not on Skjelmose/Pedersen duty. Simmons has a great sprint, and I feel like I've been waiting for him to get his breakout win for years. This could be his moment.

But my favorite American rider is Sacramento's cycling hero, Neilson Powless, who came so close to stealing the yellow jersey from Pogacar last year only for Van Aert to rip it off his back with a beautiful piece of hard riding. Powless, the first Native American rider to compete at the Tour, has been on strong form all year, with a general classification win over good competition at the Étoile de Bessèges, an impressive solo win at the Grand Prix La Marseillaise, two top-10s at Monument Classic races, and sixth at Paris-Nice. Powless can win on all sorts of terrain, and if Carapaz falters, it will be on him to carry EF. He snuck into 12th place last year, and this route favors his skills perhaps even more.

How do I watch this shit?

On NBC, Peacock, or, if you are a VPN user and want to watch for free with French commentary, France.tv (I swear this is the actual site).

Which stages are the important stages?

Both Basque openers should be fantastic, although everyone will still have their full teams around them so I am not expecting the race to roll into France with significant time gaps between contenders. The early Pyrenees stages are tricky, and I have my eye on Stage 5 with its early ascent of the Col de Soudet as both a very pretty and potentially selective stage. The race then moves across central France over the mountain ranges of the east, and reaches the Jura mountains on Stage 13 with a banger summit finish on top of the imposing Grand Colombier on Bastille Day. This is one of the hardest climbs in the Tour, even though it's not at a particularly demanding altitude.

From there it is on to the Alps, with tricky mid-mountain stages mixed in with ultra-demanding hour-long climbs. Stage 17 is this year's queen stage, with four categorized climbs and the 28-kilometer long Col de la Loze. Riders will have to sprint downhill for six kilometers after ascending the 20-percent ramps at the top of the climb, and the racing should be incredible. If the Tour isn't wrapped up by the penultimate stage, we could see some real fireworks on Stage 20's Tour de France Femmes-inspired romp across the Vosges mountains. With 3,600 vertical meters and six categorized climbs across just 133 kilometers, this stage offers precious little time or space to recover, and after Annemiek Van Vleuten won the Femmes race last year with an audacious solo effort, we could see someone try something similarly risky. The final eight kilometers are flat and slightly downhill, and the idea of someone soloing away from chasers with something real at stake could be amazing TV.

If I'm going to have a barbecue and want to watch one stage with some people, which one should I pick?

Stage 9, which finishes on top of the Puy de Dôme, the iconic Massif Central volcano. The race's first summit finish is both on a Thursday and atop a long, shallow climb that doesn't profile as the sort to incentivize real explosive attacks. The Puy, on the other hand, opens at a medium-hard gradient and briefly chills in the middle before kicking back up and ending with a long, steep ramp above 18 percent. It's unlike any other climb in the Tour.

The Puy hasn't been featured in the Tour for 35 years, though it's been a critical part of several of the most famous Tours, like in 1959 when Federico Bahamontes won a decisive time trial, in 1964 when Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor fought it out, and in 1975 when Eddy Merckx got punched in the kidneys by a spectator and lost the Tour a few days later. The Tour moved away from the Puy and its narrow, tortuous roads because of the painful logistics, which is part of what makes this stage so enticing. No spectators will be allowed on the final four kilometers of the stage, when the climb is at its steepest. There are no corners, no shade—only a long, unforgiving ramp. "It’s very, very steep. I don’t think I’ve ever been up a climb like this. There is no respite. Without any corners, you have to keep the power on the pedals endlessly," Vingegaard said after a reconnaissance ride. Stage 9 should be a beautiful run in through central France, capped off by a thrilling climb.

Thank you. I'd invite you to the barbecue but we kind of have a lot of people coming already.

All good.